Drinking Alcohol, Often Heavily, Common among People with Cancer and Long-Term Survivors

, by Carmen Phillips

Drinking alcohol increases the risk of at least seven types of cancers. For people being treated for cancer, regularly consuming a few beers or cocktails also has other potentially harmful consequences, including making their treatments less effective. And for longer-term cancer survivors, there is some evidence that regular alcohol use may increase the chances of their cancer returning.

But results from a new study suggest that this information may not be reaching people who fall into either of these two categories.

In the study, many people being treated for cancer and longer-term cancer survivors reported regularly drinking alcohol—many moderately, but some also heavily and often. According to the study’s findings, male long-term survivors and younger people being treated for cancer were among those who were particularly likely to be heavy or frequent drinkers.

The results, the study team argued, should be a wake-up call for all those involved in cancer care.

“Taken together, our findings point to the immediate and unmet need to intervene on the behalf of individuals [with cancer] with risky drinking behaviors,” wrote the study’s lead investigator, Yin Cao, Sc.D., M.P.H., of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and her colleagues August 10 in JAMA Network Open.

To conduct the study, the researchers used data from more than 15,000 people with a history of cancer who were participating in the National Institutes of Health All of Us Research Program.

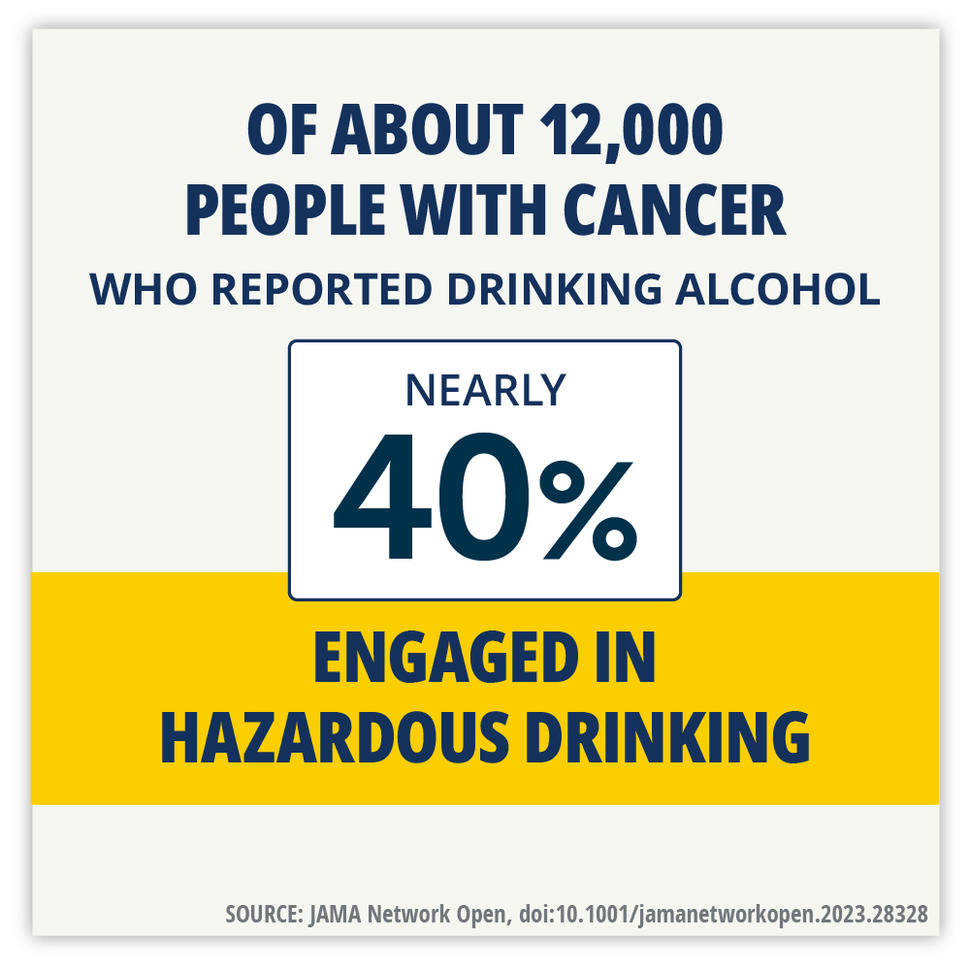

Overall, about 12,000 people in this group reported that they drink alcohol, and nearly 40% reported engaging in hazardous drinking—that is, repeated excessive alcohol use. Of those who may have been actively undergoing treatment for cancer, about 75% drank alcohol, many heavily.

By comparison, according to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 17% of US adults binge drink and 6% report heavy drinking (15 or more drinks a week for men, 8 for women).

“I was expecting that people might reduce their [alcohol] use,” especially if they were being actively treated for cancer, said Noelle LoConte, M.D., of the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center and a member of the study team. “And we didn’t … see that.”

Even as rates of heavy drinking have skyrocketed in the United States over the last few years, driven largely by the COVID pandemic, so has the realization that drinking has definite and serious harms, she continued.

“The public is really hungry to talk about” the health impact of drinking, she said. “I think we need to leverage these findings as part of that conversation.”

Taking advantage of the All of Us Research Program

The fact that drinking alcohol can cause cancer has received increasing attention in the past few years. But the potential threat it poses to people with cancer and longer-term survivors has largely been overlooked, explained Tanya Agurs-Collins, Ph.D., of the Behavioral Research Program in NCI’s Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences.

Only a few studies have tried to capture the drinking behaviors of cancer survivors, including those still undergoing treatment, said Dr. Agurs-Collins, who was not involved in this new study. And little has been done to understand how to help those who are heavier drinkers change their behavior.

“It’s time for a change,” she said.

Smaller studies, including several conducted in Europe, have found potentially harmful drinking behaviors among both people being treated for cancer and longer-term survivors.

But the All of Us study, Dr. Cao and her colleagues explained, offered a unique opportunity to take a robust look at people in these groups in the United States.

Launched in 2018, All of Us captures information on participants’ lifestyle and other behaviors and personal background via comprehensive surveys. Participants can also allow access to their electronic health records (with all identifying information removed), providing important insights on treatments received and other relevant health information.

To date, 692,000 people have enrolled in All of Us.

More than just light drinking

For the study, the research team identified 15,199 participants who, between May 2018 and January 2022, reported a history of cancer on their initial survey. About 62% were women, 75% were White, and their average age was 63.

Using the data from All of Us does come with some limitations, they acknowledged, including that cancer diagnoses were self-reported and couldn’t be verified in every case. And because of the study’s nature, it can also create certain “biases” in the data that may affect its accuracy or how relevant it is to the larger population of people with cancer and long-term survivors.

Of people who reported a history of cancer, 11,815 (78%) said they drank alcohol. The researchers categorized alcohol use based on responses to several alcohol-specific questions. They also used an assessment tool, called AUDIT-C, that was developed to study drinking behavior.

Binge drinking was most common among men, people under the age of 50, and former and current smokers. Among those who drank, binge and hazardous drinking was also much more common in those diagnosed and treated for cancer before the age of 18.

And although people who identified as Hispanic were less likely than White participants to report drinking alcohol, those who did drink were more likely to drink heavily.

| Drinking behavior | Definition | Rates among those who reported drinking |

|---|---|---|

| Exceeding moderate drinking | More than 2 drinks on a typical day when drinking | 13% |

| Binge drinking | More than 6 drinks on one occasion | 24% |

| Hazardous drinking | AUDIT-C score of 3 or more for women, 4 or more for men (scale 0–5) | 38% |

Of the participants with a history of cancer, nearly 1,800 were in active treatment for cancer at the time they completed the initial survey. Of these, 75% reported that they currently drank. Of that group, nearly 25% reported binge drinking and 38% reported hazardous drinking. The researchers could not verify, however, if the drinking occurred during treatment.

Particularly troublesome is that so many younger people—those within the 15–39 age range of adolescents and young adults, or AYAs—reported heavy drinking, said Adam DuVall, M.D., of the University of Chicago Cancer Center, who specializes in treating blood cancers in children and AYAs.

That said, Dr. DuVall continued, high alcohol use in AYAs who have or had cancer is not necessarily surprising.

Studies have shown that “high-risk behaviors are higher in [AYA] survivors,” Dr. DuVall said.

“Rates of anxiety and depression are also higher,” he continued, as well as other psychological problems like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

“Up to 40% of AYAs with cancer have PTSD of some sort,” he said. “Substance abuse and high-risk behaviors go along with that.”

A need for ways to help

More research is needed to better understand alcohol use among people with cancer, the study team wrote. But prompt action is also necessary, they stressed.

“The high prevalence of cancer survivors engaged in hazardous drinking highlights the need for immediate interventions,” they wrote.

At the moment, however, proven ways to help people with cancer limit drinking during or after completing treatment are extremely limited, Dr. DuVall said.

“There are a lot of things [clinicians] are doing on their own,” he explained. But much of the kind of work necessary to help people with substance abuse problems of any sort is beyond the realm of oncologists, he stressed.

“I’m not a specialist in psychology or behavioral interventions,” he continued. “We need to partner with folks [in those specialties] to figure out what we can do to help our patients with these issues.”

Dr. LoConte said that she has direct conversations with her patients about drinking and other behaviors that could affect their treatment. And often she directs some of that discussion to family members and loved ones who are with the patient, essentially recruiting them to help manage the patient’s drinking.

“I try to normalize asking [patients] things like, if they’re drinking, how much and how they feel it affects them,” she explained.

She agreed with Dr. DuVall that oncologists, and other clinicians they work with, are stretched thin and rarely have the time or training to appropriately handle these issues.

Greater collaboration with other specialties and clinicians who regularly interact with people with cancer, such as oncology nurses, to develop ways to reduce risky drinking behaviors will be needed moving forward, Dr. Agurs-Collins said.

Given the study’s findings, “there’s also a need to better understand why so many cancer survivors have such high alcohol consumption,” she continued.

Could it be related to untreated pain, depression, or other reasons? “We need to better understand these root causes and how best to address them,” she said.