Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma (DIPG)

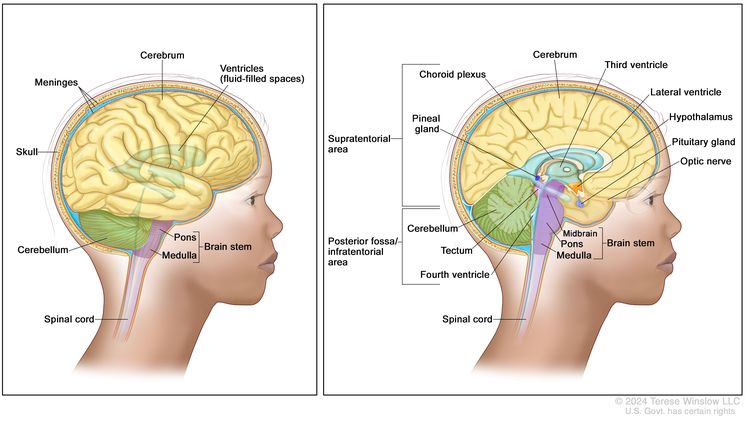

Diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG) is a fast-growing type of brain tumor that starts in the part of the brain stem called the pons. The brain stem is the part of the brain above the back of the neck that is connected to the spinal cord. The pons controls many vital functions such as breathing, heart rate, and blood pressure, and the nerves and muscles used in seeing, hearing, walking, talking, and eating. DIPG is a glioma, meaning it starts in the brain stem's glial cells. Glial cells support and protect the brain's nerve cells.

In the United States, about 300 children are diagnosed with DIPG each year. DIPG primarily affects children between the ages of 5 and 10 years but can occur in younger children and teens. DIPG is rare in adults.

Causes and risk factors for DIPG

DIPG is caused by certain changes to the way glial cells function, especially how they grow and divide into new cells. Often, the exact cause of the cell changes that lead to DIPG is unknown. To learn more about how cancer develops, see What Is Cancer?

A risk factor is anything that increases the chance of getting a disease. There are no known risk factors for DIPG.

Symptoms of DIPG

The symptoms of DIPG depend on:

- where the tumor forms in the brain

- the size of the tumor and whether it has spread throughout the brain stem

- how fast the tumor grows

- your child's age and stage of development

DIPG symptoms appear rapidly. It's important to check with your child's doctor immediately if your child has:

- trouble with eye movement (the eye is turned inward)

- vision problems

- problems with talking, chewing, and swallowing

- drooping on one side of the face

- morning headache or headache that goes away after vomiting

- nausea and vomiting

- weakness in the arms or legs

- loss of balance and trouble walking

- changes in behavior

- trouble learning in school

These symptoms may be caused by problems other than DIPG. The only way to know for sure is to see your child's doctor.

Tests to diagnose DIPG

If your child has symptoms that suggest a DIPG, their doctor will need to find out if these are due to DIPG or some other problem. The doctor will ask when the symptoms started and how often your child has been having them. They will also ask about your child's personal and family medical history and do a physical exam, including a neurological exam. Depending on these results, they may recommend other tests. If your child is diagnosed with DIPG, the results of these tests will help you and your child's doctor plan treatment.

The tests and procedures used to diagnose a DIPG may include:

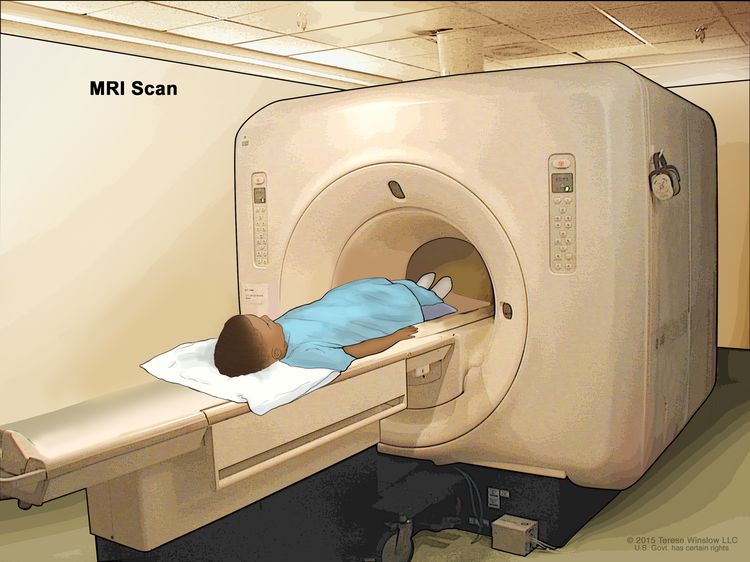

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with or without gadolinium

MRI uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the brain. A substance called gadolinium is injected into a vein. The gadolinium collects around the cancer cells so they show up brighter in the picture. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI).

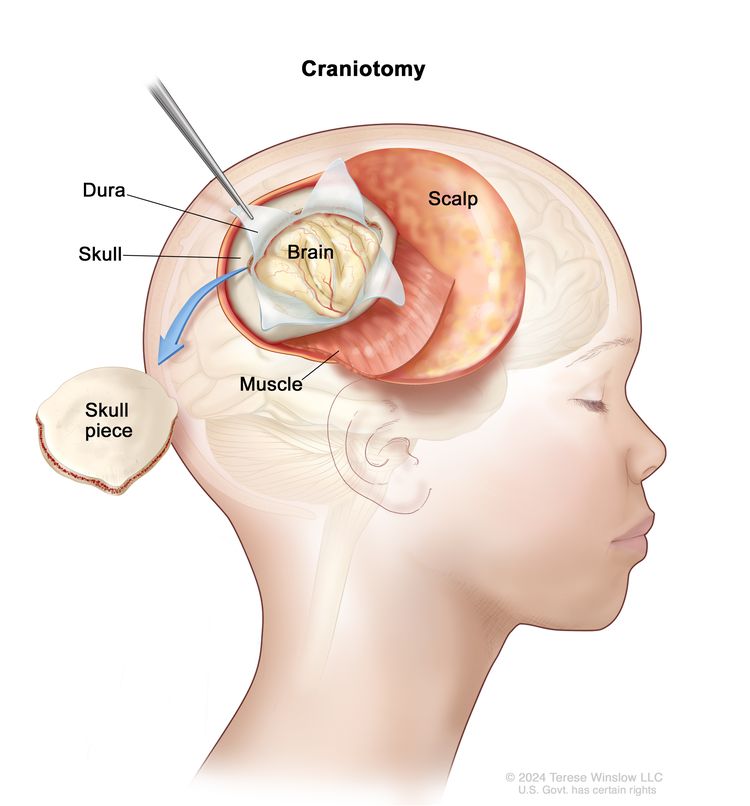

Biopsy

Your child's doctor will discuss whether a biopsy is an option. A biopsy is a procedure in which a surgeon removes a sample of tumor tissue from the pons. A stereotactic biopsy, which involves using an imaging technique to help precisely find and remove the tumor tissue, is usually done. A pathologist will study the biopsy sample and provide the results of their analysis in a pathology report. If the pathologist finds that your child has DIPG, the pathology report will provide information about the cancer that can help guide treatment decisions.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry is a laboratory test that uses antibodies to check for certain antigens (markers) in a sample of a patient’s tissue. The antibodies are usually linked to an enzyme or a fluorescent dye. After the antibodies bind to a specific antigen in the tissue sample, the enzyme or dye is activated, and the antigen can then be seen under a microscope. This type of test is used to help diagnose cancer and to help tell one type of cancer from another type.

Getting a second opinion

You may want to get a second opinion to confirm your child’s diagnosis and treatment plan. If you seek a second opinion, you will need to get medical test results and reports from the first doctor to share with the second doctor. The second doctor will review the pathology report, slides, and scans. They may agree with the first doctor, suggest changes to the treatment plan, or provide more information about your child’s cancer.

To learn more about choosing a doctor and getting a second opinion, see Finding Cancer Care. You can contact NCI's Cancer Information Service via chat, email, or phone (both in English and Spanish) for help finding a doctor or hospital that can provide a second opinion. For questions you might want to ask at your child's appointments, see Questions to Ask Your Doctor.

Who treats children with DIPG?

A pediatric oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating children with cancer, oversees treatment for DIPG. The pediatric oncologist works with other health professionals who are experts in treating children with brain tumors and also specialize in other areas of medicine. Other specialists may include:

Types of treatment for DIPG

There are different types of treatment for children and adolescents with DIPG. You and your child's care team will work together to decide treatment. Many factors will be considered, such as your child's overall health and whether the cancer is newly diagnosed or has come back.

Your child's treatment plan will include information about the cancer, the goals of treatment, treatment options, and the possible side effects. It will be helpful to talk with your child’s cancer care team before treatment begins about what to expect. For help every step of the way, see our booklet, Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents.

Types of treatment your child might have include:

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. DIPG is treated with external-beam radiation therapy. This type of radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the area of the body with cancer.

Several months after radiation therapy to the brain, imaging tests may show changes to the brain tissue. These changes may be caused by the radiation therapy or may mean the tumor is growing. It is important to be sure the tumor is growing before any more treatment is given.

To learn more, see External-Beam Radiation Therapy for Cancer and Radiation Therapy Side Effects.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (also called chemo) uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells. Chemotherapy either kills the cancer cells or stops them from dividing.

To treat a DIPG in infants, chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein. When given this way, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body. Chemotherapy drugs that cross the blood-brain barrier and reach tumor cells in the brain are used.

Because radiation therapy to the brain can affect growth and brain development in young children, chemotherapy may be given to delay or reduce the need for radiation therapy.

To learn more, see Chemotherapy to Treat Cancer.

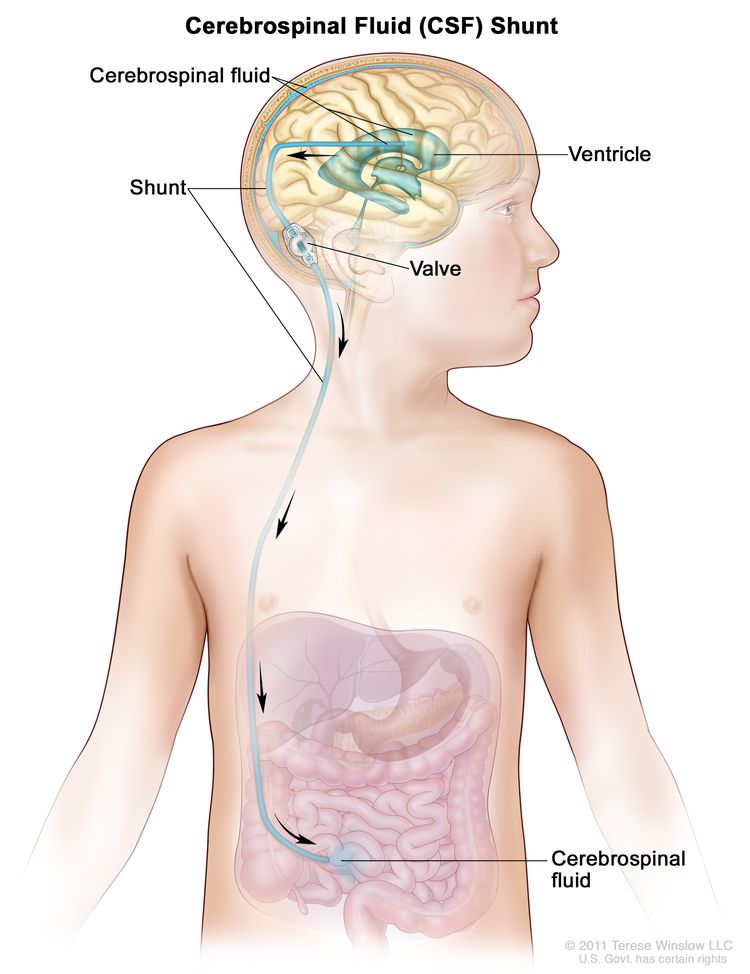

Surgery to place a shunt

Sometimes children with a DIPG have increased fluid around the brain or spinal cord. They may need surgery to place a shunt (long, thin tube) in a ventricle (fluid-filled space) of the brain and thread it under the skin to another part of the body, usually the abdomen. The shunt carries extra fluid away from the brain so it may be absorbed elsewhere in the body. This decreases the fluid and pressure on the brain or spinal cord.

Clinical trials

A treatment clinical trial is a research study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain information on new treatments for patients with cancer. Because cancer in children is rare, taking part in a clinical trial should be considered.

Use our clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment. Clinical trials supported by other organizations can be found on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

To learn more, see Clinical Trials Information for Patients and Caregivers.

Treatment of DIPG

Palliative care is an important part of your child's treatment plan throughout their cancer journey. It includes physical, psychological, social, and spiritual support for your child and family. The goal of palliative care is to help control symptoms and give your child the best quality of life possible.

Treatment of newly diagnosed childhood DIPG may include:

- external-beam radiation therapy

- chemotherapy (to treat infants)

Treatment of DIPG that is progressive (getting worse) or has come back after treatment may include radiation therapy, if the cancer responded when first treated with radiation therapy.

Prognosis and prognostic factors for DIPG

If your child has been diagnosed with DIPG, you likely have questions about your child's chances of survival. The likely outcome or course of a disease is called prognosis.

Doctors consider these and other factors when making a prognosis for DIPG:

- where the tumor is found in the brain and if it has spread within the brain stem

- your child's age at diagnosis

- how long your child has had symptoms prior to diagnosis

- whether the tumor has a certain change to H3 K27m

DIPG is a challenging cancer to treat because of its location in the brain, how fast it progresses, and the way it spreads into healthy tissue. Unfortunately, most children with DIPG do not live longer than 2 years after diagnosis. Your child's cancer care team is in the best position to talk with you about your child's prognosis.

Follow-up care

As your child goes through treatment, they will have follow-up tests or check-ups. Some of the tests that were done to diagnose the cancer may be repeated to see how well the treatment is working. Decisions about whether to continue, change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests.

Some of the tests will continue to be done from time to time after treatment has ended. The results of these tests can show if your child's condition has changed or if the cancer has come back. If the results of imaging tests done after treatment for DIPG show a mass in the brain, a biopsy may be done to find out if it is made up of dead tumor cells or if new cancer cells are growing.

Coping with your child's cancer

When your child has cancer, every member of the family needs support. Taking care of yourself during this time is important. Talk with your child's treatment team and people in your family and community for support with coping with the emotional and physical stress that comes with a cancer diagnosis. To learn more, see Support for Families When a Child Has Cancer and the booklet Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents.

Related resources

For more childhood cancer information and other general cancer resources, see: