Leukemia Treatment for Adults

The mainstays of leukemia treatment for adults have been chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and stem cell transplantation. Over the last two decades, targeted therapies have also become part of the standard of care for some types of leukemia. These treatments target proteins that control how cancer cells grow, divide, and spread. Different types of leukemia require different combinations of therapies. For a complete list of all currently approved drugs, see Drugs Approved for Leukemia.

Although much progress has been made against some types of leukemia, others still have relatively poor rates of survival. And, as the population ages, there is a greater need for treatment regimens that are more effective and less toxic than standard chemotherapy.

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) Treatment

Adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is a type of cancer in which the bone marrow makes too many lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell). It usually gets worse quickly and needs rapid treatment. Some recent research includes:

Combining less-toxic therapies

The intensive chemotherapy treatments used for ALL have serious side effects that many older patients cannot tolerate. Targeted therapies may have fewer side effects than chemotherapy. Clinical trials are now testing whether combinations of these types of therapies can be used instead of chemotherapy for older patients with a form of ALL called B-cell ALL.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapies are treatments that help the body’s immune system fight cancer more effectively. Immunotherapy strategies being used or tested in ALL include:

CAR T-cell therapy

CAR T-cell therapy is a type of treatment in which a patient’s own immune cells are genetically modified to treat their cancer.

- Currently, one type of CAR T cell therapy is approved for the treatment of some children and young adults with B-cell precursor ALL. This CAR T cell therapy is now being explored for use in older adults with B-cell ALL.

- A second CAR T-cell therapy has also been approved for adults with B-cell precursor ALL that has not responded to treatment or has returned after previous treatment.

CAR T cell therapies are now being explored for other uses in ALL. For example, scientists hope that it will be possible to use CAR T-cell therapy to delay—or even replace—stem-cell transplantation in older, frailer patients.

Bispecific T-cell engagers

Another immunotherapy being tested in ALL is bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs). These drugs attach to immune cells and cancer cells, enabling the immune cells to easily find and destroy the cancer cell by bringing them closer together.

Once such BiTE, called blinatumomab (Blincyto), was recently shown to improve survival for people with ALL who are in remission after chemotherapy, even when there is no trace of their disease. In 2024, FDA approved blinatumomab for adult and pediatric patients one month and older with a specific type of B-cell precursor ALL. The approval is for use as part of consolidation chemotherapy, which is treatment that is given after cancer has disappeared following initial therapy.

Improving treatment for adolescents and young adults (AYAs)

An intensive treatment regimen developed for children with ALL has been found to also improve outcomes for newly diagnosed AYA patients. The pediatric regimen more than doubled the median length of time people lived without their cancer returning compared with an adult treatment regimen. Further studies are now testing the addition of targeted therapies to the combination.

Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) Treatment

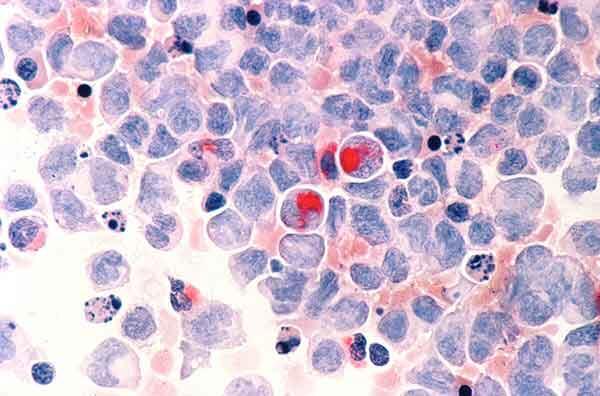

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is the most common type of acute leukemia in adults. It can cause a buildup of abnormal red blood cells, white blood cells, or platelets.

AML tends to be aggressive and is harder to treat than ALL. However, AML cells sometimes have gene changes that cause the tumors to grow but can be targeted with new drugs. Researchers are starting to look at whether genomic sequencing of tumor cells can help doctors choose the best treatment (such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy, stem-cell transplant, or a combination of therapies) for each patient. Scientists are also testing other ways to treat AML.

Targeted therapies

Targeted therapies recently approved to treat AML with certain gene changes include Enasidenib (Idhifa), Olutasidenib (Rezlidhia), Ivosidenib (Tibsovo), Venetoclax (Venclexta), Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg), Midostaurin (Rydapt), Gilteritinib (Xospata), Glasdegib (Daurismo), and Quizartinib (Vanflyta).

An NCI-supported precision medicine study called MyeloMATCH is now enrolling people with newly diagnosed AML or a related but less aggressive cancer called myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). Participants will undergo genomic testing of blood and bone marrow samples to see if they have specific genetic alterations that can be matched to corresponding targeted therapies.

Other ways to treat AML

- Testing newer targeted therapies. Researchers continue to develop new drugs to shut down proteins that some leukemias need to grow. For example, new drugs called menin inhibitors stop cancer-promoting genes from being expressed.

- Studying ways to target AML cells indirectly. These include testing ways to make cancer cells more vulnerable to new and existing treatments.

- Targeting AML and related conditions. MDS can eventually progress to AML. Researchers are testing HDAC inhibitors and other drugs that alter how genes are switched on and off in both MDS and AML.

- Reducing side effects. Some older adults cannot tolerate the intensive treatments most commonly used for AML. Studies have recently found that several drug combinations can help older people with AML live longer while avoiding many serious side effects. New treatments to relieve symptoms of MDS have also been developed.

- Immunotherapy. CAR T cells and BiTEs are being tested in people with AML.

Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia (CML) Treatment

Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) is a type of cancer in which the bone marrow makes too many granulocytes (a type of white blood cell). These granulocytes are abnormal and can build up in the blood and bone marrow so there is less room for healthy white blood cells, red blood cells, and platelets. CML usually gets worse slowly over time.

Blocking an abnormal protein

Most people with CML have a specific chromosome alteration called the Philadelphia chromosome, which produces an abnormal protein that drives the growth of leukemia cells. Targeted therapies that block this abnormal protein—imatinib (Gleevec), nilotinib (Tasigna), dasatinib (Sprycel), and ponatinib (Iclusig)—have radically changed the outlook for people with CML, who now have close to a normal life expectancy.

Testing new combination therapies

Some people with CML continue to have detectable cancer cells in their body even after long-term treatment with drugs that target the protein produced by the Philadelphia chromosome. NCI-supported trials are testing whether the addition of immunotherapy or other targeted therapies to these drugs can reduce the number of CML cells in such patients.

Looking at whether patients can stop taking therapy

Researchers have found that some drugs that target the protein produced by the Philadelphia chromosome can be safely stopped in some CML patients rather than taken for life. These patients must undergo regular testing to ensure the disease has not come back.

Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) Treatment

Like ALL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a type of cancer in which the bone marrow makes too many lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell). But unlike ALL, CLL is slow growing and worsens over time.

Targeted therapy

Ibrutinib (Imbruvica). The targeted therapy ibrutinib (Imbruvica) was the first non-chemotherapy drug approved to treat CLL. It shuts down a signaling pathway called the B-cell receptor signaling pathway, which is commonly overactive in CLL cells. Depending on people’s age, ibrutinib may be given in combination with another targeted drug, rituximab (Rituxan).

Clinical trials have shown that ibrutinib benefits both younger and older patients with CLL.

Venetoclax (Venclexta) and obinutuzumab (Gazyva). In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the second chemotherapy-free initial treatment regimen for CLL, containing the targeted therapies venetoclax (Venclexta) and obinutuzumab (Gazyva).

Other combinations of these drugs plus ibrutinib are now being used or tested for CLL, including

- ibrutinib and venetoclax in people with newly diagnosed CLL

- ibrutinib, obinutuzumab, and venetoclax in older adults with newly diagnosed CLL

- ibrutinib and obinutuzumab with or without venetoclax in younger adults with newly diagnosed CLL

An ongoing trial at NCI is also testing whether giving the combination of venetoclax and obinutuzumab to some people with CLL before symptoms develop can help them live longer overall.

Zanubrutinib (Brukinsa). In early 2023, the FDA approved a drug that works in a similar manner to ibrutinib, called zanubrutinib (Brukinsa), for people with CLL. A large study showed that zanubrutinib alone has fewer side effects and is more effective than ibrutinib for people whose leukemia has returned after initial treatment. More research is now needed to understand how to best combine zanubrutinib with other newer therapies, such as venetoclax.

CAR T-cell therapy

CAR T-cell therapy is also being tested in adults with CLL. Researchers would like to know if using this type of immunotherapy early in the course of treatment would be more effective than waiting until the cancer recurs.

Hairy Cell Leukemia (HCL) Treatment

Hairy cell leukemia (HCL) is a type of cancer in which the bone marrow makes too many lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell). The disease is called hairy cell leukemia because the abnormal lymphocytes look "hairy" when viewed under a microscope. This rare type of leukemia gets worse slowly, or sometimes does not get worse at all.

Combinations of drugs

Researchers are studying combinations of drugs to treat HCL. For example, in a recent small study, a combination of two targeted therapies—vemurafenib (Zelboraf) and rituximab (Rituxan)—led to long-lasting remissions for most participants with HCL that had come back after previous treatments. More drug combinations are currently being tested in clinical trials.

Leukemia Treatment for Children

For the two most common types of leukemia, AML and ALL, standard leukemia treatments for children have been chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and stem-cell transplant. Despite great improvements in survival for children with many types of leukemia, some treatments don't always work. Also, some children later experience a relapse of their disease. Others live with the side effects of chemotherapy and radiation therapy for the rest of their lives, highlighting the need for less toxic treatments.

Now researchers are focusing on targeted drugs and immunotherapies for the treatment of leukemia in children. Newer chemotherapy drugs are also being tested.

Targeted Therapies

Targeted therapies that have been approved or are being studied for children with leukemia include:

- imatinib (Gleevec) and dasatinib (Sprycel), which are approved for the treatment of children with CML as well as those with a specific type of ALL. The approvals are for children whose cancer cells have the Philadelphia chromosome.

- sorafenib (Nexavar), which has been studied in combination with standard chemotherapy for children with AML whose leukemia has changes in a gene called FLT3. The addition of sorafenib to standard treatment was safe, and its addition may improve survival time free from leukemia. Other ongoing clinical trials are testing drugs that target FLT3 more specifically than sorafenib (such as gilteritinib).

- larotrectinib (Vitrakvi), which is being tested in children with leukemia that has a specific change in a gene called NTRK.

More possible targets for the treatment of childhood cancers are discovered every year, and many new drugs that could potentially be used to treat cancers that have these targets are being tested through the Pediatric Preclinical In Vivo Testing Consortium (PIVOT).

Immunotherapy

CAR T-cell therapy has recently generated great excitement for the treatment of children with relapsed ALL. One CAR T-cell therapy, tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah), was approved in 2017 for some children with relapsed ALL.

Researchers continue to address remaining challenges about the use of CAR T-cell therapy in children with leukemia:

- Sometimes, leukemia can become resistant to tisagenlecleucel. Researchers in NCI’s Pediatric Oncology Branch have developed CAR T cells that target leukemia cells in a different way. An ongoing clinical trial is testing whether the combination of these two types of CAR T cells can provide longer-lasting remissions.

- CAR T cells are currently only approved for use in leukemia that has relapsed or proved resistant to standard treatment. A clinical trial from the Children's Oncology Group (COG) is now testing tisagenlecleucel as part of first-line therapy in children with ALL at high risk of relapse.

- More research is needed to understand which children who receive CAR T cells are at high risk of developing resistance to treatment. Researchers also plan to test whether strategies such as combining CAR T-cell therapy with other immunotherapies may help prevent resistance from developing.

- Other research, both in NCI’s Pediatric Oncology Branch and at other institutions, is focused on creating CAR T-cell therapies that work for children with other types of childhood leukemia, such as AML. Several clinical trials of these treatments, including one led by NCI researchers, are now under way.

Two other drugs that use the body’s immune system to fight cancer have shown promise for children with leukemia:

- A drug called blinatumomab (Blincyto) is a type of immunotherapy called a bispecific T-cell engager (BiTE). These drugs attach to immune cells and cancer cells, enabling the immune cells to easily find and destroy the cancer cell by bringing them closer together. Blinatumomab has been approved by the FDA for children with ALL who have relapsed after initial treatment.

- In clinical trials, the drug was shown to be more effective than chemotherapy in treating ALL that has relapsed in children and young adults.

- An NCI-supported trial is now testing the drug as part of treatment for newly diagnosed ALL in children, adolescents, and young adults.

- A drug called inotuzumab ozogamicin (Besponsa) is being tested in children with relapsed B-cell ALL. This drug consists of an antibody that can bind to cancer cells linked to a drug that can kill those cells. An NCI-supported trial is also testing the drug as part of treatment for newly diagnosed ALL in children and adolescents at higher risk of relapse.

Chemotherapy

In addition to targeted therapies and immunotherapies, researchers are also working to develop new chemotherapy drugs for leukemia and find better ways to use existing drugs. In 2018, a large clinical trial showed that adding the drug nelarabine (Arranon) to standard chemotherapy improves survival for children and young adults newly diagnosed with T-cell ALL.

Other drugs are being tested that may make standard chemotherapy drugs more effective. These drugs include venetoclax, which has been approved for older adults with some types of leukemia and is now being tested in children.

Survivorship

Children’s developing brains and bodies can be particularly sensitive to the harmful effects of cancer treatment. Because many children treated for cancer go on to live long lives, they may be dealing with these late effects for decades to come.

The NCI-funded Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, ongoing since 1994, tracks the long-term harmful effects of treatments for childhood cancer and studies ways to minimize these effects. NCI also funds research into addressing ways to help cancer survivors cope with and manage health issues stemming from cancer treatment, as well as into altering existing treatment regimens to make them less toxic in the long term.

For example, one study found that, in children with ALL, radiation therapy to prevent the cancer from returning in the brain is likely unnecessary. The study found that radiation can even be omitted for children at the highest risk of the cancer coming back, reducing the risk of future problems with thinking and memory, hormone dysfunction, and other side effects of radiation to the brain.

Preventing and Treating Graft Versus Host Disease

Many people with leukemia—both adults and children—have a stem-cell transplant as part of their treatment. If the new stem cells come from a donor, the immune cells they produce may be able to attack any cancer cells that remain in the body.

But sometimes, immune cells produced by donor stem cells attack healthy tissues of the body instead. This condition, called graft versus host disease (GVHD), can affect nearly every organ and can cause many painful and debilitating symptoms.

In recent years, several drugs have been approved by the FDA for the treatment of GVHD, including:

- ibrutinib, which is also used as a treatment for some types of leukemia

- ruxolitinib (Jakafi)

- belumosudil (Rezurock)

Researchers are also testing ways to prevent GVHD from developing in the first place. For example, a recent study found that removing certain immune cells from donated stem cells before they are transplanted may reduce the risk of chronic GVHD without any apparent increase in the likelihood of relapse.

NCI-Supported Research Programs

Many NCI-funded researchers working at the NIH campus and across the United States and the world are seeking ways to address leukemia more effectively. Some research is basic, exploring questions as diverse as the biological underpinnings of cancer. And some is more clinical, seeking to translate this basic information into improving patient outcomes. The programs listed below are a small sampling of NCI’s research efforts in leukemia.

NCI’s Leukemia Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPORE) promotes collaborative, interdisciplinary research. SPORE grants involve both basic and clinical/applied scientists working together. They support the efficient movement of basic scientific findings into clinical settings, as well as studies to determine the biological basis for observations made in individuals with cancer or in populations at risk for cancer.

The Targeting Fusion Oncoproteins in Childhood Cancers (TFCC) Network is forming a collaborative team of investigators to advance the understanding of how fusion proteins contribute to pediatric cancers, and how they might be targeted with new treatments. Fusion proteins, which can occur when parts of different chromosomal regions are joined, may drive the development of many cancers in children.

NCI has also formed partnerships with the pharmaceutical industry, academic institutions, and individual investigators for the early clinical evaluation of innovative cancer therapies. The Experimental Therapeutics Clinical Trials Network (ETCTN) was created to evaluate these therapies using a coordinated, collaborative approach to early-phase clinical trials.

The Pediatric Early-Phase Clinical Trials Network was established to help identify and develop effective new drugs for children and adolescents with cancer. The network’s focus is on phase I and early phase II trials, as well as pilot studies of novel drugs and treatment regimens to determine their tolerability.

NCI’s Pediatric Preclinical In Vivo Testing Consortium (PIVOT) develops mouse models to allow early, rapid testing of new drugs for pediatric cancers, including leukemia. The models are all derived from tissue samples taken from patients’ tumors. The consortium partners both with commercial drug companies and with drug development efforts at universities and cancer centers.

The NCI-supported Children’s Oncology Group develops and conducts both clinical trials of initial treatments and clinical trials for after cancer relapse for children and adolescents with ALL, AML, and CML.

Researchers in NCI’s Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics (DCEG) investigate novel, molecular biomarkers for leukemia, as well as clarify relationships of established risk factors. Studies include those looking at environmental and workplace exposure, families with multiple leukemia cases, and inherited bone marrow failure syndromes to name a few.

Clinical Trials

NCI funds and oversees both early- and late-phase clinical trials to develop new treatments and improve patient care. Search NCI-Supported Clinical Trials to find leukemia-related trials now accepting patients.

Leukemia Research Results

The following are some of our latest news articles on leukemia research:

- Blinatumomab Boosts Chemotherapy as Initial Treatment for Some Kids with ALL

- Quizartinib Approval Adds New Treatment Option for AML, Including in Older Patients

- Blinatumomab Increases Survival for Infants with an Aggressive Type of ALL

- Revumenib Shows Promise in Treating Advanced Acute Myeloid Leukemia

- Help Desk for Oncologists Treating People with a Rare Leukemia Pays Big Dividends

- Zanubrutinib’s Approval Improves Targeted Treatment for CLL