FDA Approves Engineered Cell Therapy for Advanced Synovial Sarcoma

, by Edward Winstead

On August 2, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a cellular therapy called afamitresgene autoleucel, or afami-cel (Tecelra), to treat some people with metastatic synovial sarcoma, a type of soft tissue sarcoma. The decision marks the first time the agency has approved a treatment called a T-cell receptor (TCR) therapy for cancer.

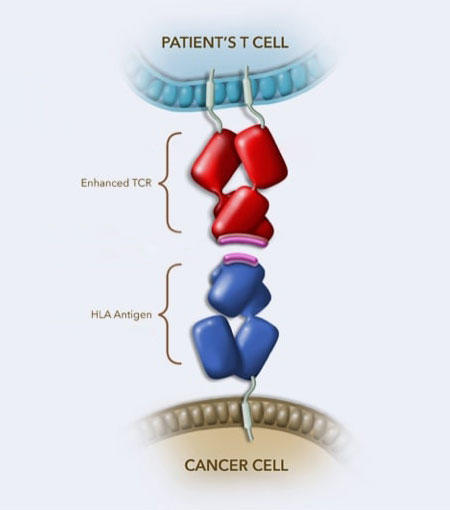

Afami-cel is made using a patient’s own T cells, a type of immune cell. The T cells are collected from a patient’s blood, genetically engineered in a lab, and then infused back into the person. The genetic engineering produces a T-cell receptor that is better able to recognize and bind to a protein called MAGE-A4 in cancer cells.

Afami-cel is approved for patients who have been treated with chemotherapy and whose tumors test positive for the presence of MAGE-A4 and certain types of HLA proteins.

The approval was based on a clinical trial that included 44 people with metastatic synovial sarcoma. The therapy shrank tumors in 19 participants (43%), and the median duration of response—how long the treatment kept tumors from growing—was 6 months. The trial was sponsored by the drug’s maker, Adaptimmune.

“Afami-cel will be the new standard treatment for patients with metastatic synovial sarcoma who are eligible for the therapy,” said Sandra D’Angelo, M.D., of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, who led the trial.

She noted that afami-cel is similar to chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies that have been approved for treating certain blood cancers since 2017. “With both CAR T and T-cell receptor therapies, we are giving immune cells the ability to fight cancer,” Dr. D’Angelo said.

Addressing the need for new treatments for synovial sarcoma

Synovial sarcoma can arise in various soft tissues, such as muscle or ligament. It can occur in extremities and near joints such as the wrist or ankle. The cancer is rare, with fewer than 1,000 people diagnosed with the disease in the United States each year.

One-third of people with synovial sarcoma will be diagnosed under the age of 30, and treatment options are limited.

When the disease has not spread within the body, treatment typically involves surgery to remove the tumor. Radiation therapy and/or chemotherapy may also be used if the tumor is larger, returns after being removed, or has spread beyond its original location.

About half of the patients with this cancer develop metastatic disease, which is not curable. The standard treatment for patients with metastatic disease is chemotherapy.

It has been more than a decade since FDA approved a new therapy for the disease. There is an “exceedingly high need” for new treatment options for patients, Dr. D’Angelo said.

Targeting a protein inside cancer cells

Afami-cel, which takes about 6 weeks to manufacture, is administered through a patient’s bloodstream in a single dose.

The genetic engineering aims to solve a problem with naturally occurring T-cell receptors—they do not always detect and bind tightly to cancer cells. Secure binding allows the immune cells to kill the cancer cells.

Whereas CAR T-cell therapies latch onto proteins on the surface of cancer cells, T-cell receptor therapies can target proteins normally found inside the cell. Afami-cel, for instance, targets MAGE-A4, which is found in various tumors, including ovarian and head and neck cancers.

“We have found that synovial sarcomas tend to express MAGE-A4,” said David Hong, M.D., of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, who led one of the first clinical trials to evaluate afami-cel in people.

HLA proteins present part of the MAGE-A4 protein to T cells, alerting the immune system to the presence of cancer, he noted.

Some complete responses

Afami-cel was approved using the FDA’s accelerated approval pathway. In the clinical trial that led to the approval, many of the 44 participants with synovial sarcoma had received multiple prior therapies.

Of the 19 people whose tumors shrank following the treatment, two had complete responses, meaning their tumors went away and did not return during the 3-year study period.

The most common side effects associated with afami-cel included nausea, vomiting, fatigue, and infections. About 70% of participants experienced cytokine release syndrome, a type of immune system overreaction. Most cases were mild and could be managed with other medications, the researchers reported.

“Although the treatment’s side effects are minimal,” Dr. Hong said, “the therapy should be given mainly at academic cancer centers that have experience with cellular therapies.”

Experts are needed, for example, to help prepare patients to receive the cells. To make room for the engineered cells in the bone marrow, doctors give patients high-dose chemotherapy. The process, lymphodepletion, can have side effects, such as reduced numbers of white blood cells.

Another challenge is how to limit the cancer’s progression during the 6-week period when the therapy is being manufactured, Dr. Hong noted. “During this time, some patients might receive chemotherapy to help control the growth of their tumors,” he said.

In the trial, about 40% of participants had to receive some form of treatment, or “bridging therapy,” to keep their cancer or symptoms in check while their T-cell receptor therapy was manufactured.

Treating other solid tumors with T-cell receptor therapy

A second-generation version of afami-cel has shown promise in a clinical trial involving people with various types of cancer, including esophageal cancer. The therapy, known as uza-cel, also targets MAGE-A4.

“This work demonstrates the feasibility of conducting cutting-edge research with new treatment approaches in rare diseases, such as synovial sarcoma,” Dr. D’Angelo said.

The demonstration that T-cell receptor therapy can treat solid tumors “is an important scientific milestone,” Dr. Hong said. He predicted that new and more effective cell therapies would be tested in patients in the coming years.

“Scientists are developing innovative ways to modify T cells to make them more resilient and stronger,” Dr. Hong said. “It’s an exciting time in cancer drug development.”