FDA Approves New Initial Treatment Option for Some Metastatic Prostate Cancers

, by Shana Spindler

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the combination of enzalutamide (Xtandi) with talazoparib (Talzenna) as an initial treatment for some people with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. This is a form of prostate cancer that has spread from the prostate to other parts of the body and no longer responds to standard hormone-blocking treatments.

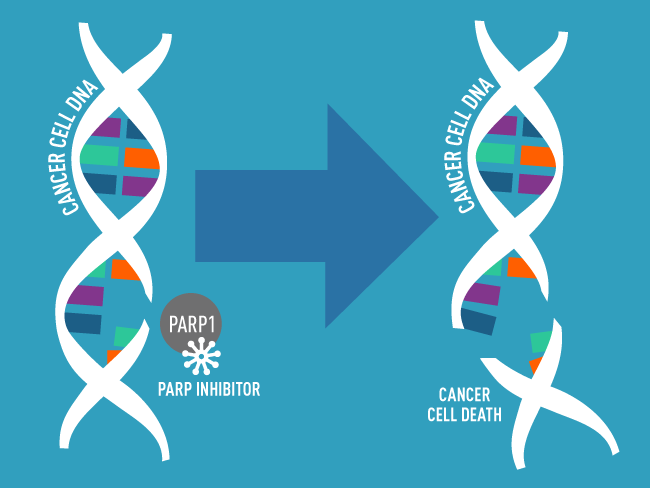

The talazoparib and enzalutamide combination is approved to treat people whose prostate cancer has an alteration in a specific group of genes involved in repairing damaged DNA. Talazoparib works by blocking the DNA repair activities of a protein called PARP, which in combination with altered DNA repair genes, makes it harder for cancer cells to survive. Enzalutamide works by blocking hormones from fueling cancer cell growth.

The approval, announced on June 20, makes talazoparib the third PARP-blocking drug to be cleared by the agency to treat prostate cancer. FDA based the approval on a set of data from a large, randomized phase 3 clinical trial called TALAPRO-2—funded by Pfizer, the maker of talazoparib.

The trial included two separate cohorts of participants, one of which enrolled only men whose tumors had alterations in DNA repair genes.

The new approval was based on findings from this cohort, in which participants treated with the drug combination lived longer without their cancer getting worse than those treated with the standard treatment of enzalutamide alone. At nearly 3 years after starting the talazoparib and enzalutamide treatment, about 50% of patients whose tumors had one of these changes were still alive without their cancer getting worse. For those who received enzalutamide alone, that number was about 20%.

Findings from this part of the trial were presented in June at the 2023 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting.

About a quarter of men with prostate cancer have an alteration in a DNA repair gene, said Neeraj Agarwal, M.D., a medical oncologist at the University of Utah Huntsman Cancer Institute, who co-led the study. Because prostate cancer is so common, he added, many people will be eligible to receive the combination treatment even with approval limited to this subset of patients.

But some experts in prostate cancer treatment cautioned that patients in the trial have not been followed long enough to know if the drug combination improves how long patients live overall.

That’s an important missing piece of information, said Fatima Karzai, M.D., of the Genitourinary Malignancies Branch in NCI’s Center for Cancer Research. The data “need more time so we know how participants who may harbor these alterations will do,” Dr. Karzai explained.

In particular, it’s unclear if the enzalutamide–talazoparib combination provides more benefit to patients than the current practice of using enzalutamide as an initial treatment followed by a PARP inhibitor only after their cancer starts to get worse.

This latter option, she noted, offsets some of the combination’s side effects, which were more severe than those of the standard treatment.

Treatment intensification to prevent progression

In 2020, FDA approved the first PARP inhibitors for the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer with altered DNA repair genes. Both approvals covered use of the drugs as second-line treatments—that is, only for patients whose cancer was no longer responding to an earlier hormone therapy.

Although the initial approvals were promising, Dr. Agarwal said, he wondered whether waiting to offer PARP inhibitors until after the standard treatment stopped working might be preventing these therapies from helping more patients; as many as 40% of these patients stop treatments when their disease progresses. This high attrition, he noted, is one of the reasons why using stronger therapy up front has worked in advanced prostate cancer.

So, he wanted to test using a PARP inhibitor during initial therapy, when more patients are feeling better and more enthusiastic about receiving it, he said.

Rather than using a PARP inhibitor alone as an initial treatment, he continued, they decided to combine it with a powerful hormone therapy (in this case enzalutamide), a decision based on data from laboratory studies showing that these drugs may be even more effective when combined.

The researchers enrolled two different cohorts of participants to test the combination therapy in a broader cohort of men and in those who are most likely to benefit from the new treatment. The first cohort included 805 men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, regardless of whether their tumors had any alterations in 12 specific DNA repair genes. The trial’s second cohort was limited to 399 men whose tumors had alterations in any of the 12 genes.

Participants in both cohorts received either enzalutamide plus talazoparib or enzalutamide plus a placebo, given by pill once daily. Then, the researchers measured the length of time until cancer growth could be seen on standard imaging scans, called radiographic progression-free survival.

In the cohort of men whose tumors had alterations in DNA repair genes—the part of the trial on which the new approval is based—the median amount of time until cancer growth could be seen on a scan was about 14 months for those who received enzalutamide alone. But among those who received the combination treatment, too few people had experienced a worsening of their cancer to even determine the median radiographic profession-free survival in this cohort.

Importantly, on standardized questionnaires given to these patients, those who received enzalutamide and talazoparib reported a better quality of life for longer than patients treated only with enzalutamide, Dr. Agarwal noted.

Although the drug combination was approved for people whose tumors have alterations in any of 12 DNA repair genes, when the researchers looked at the specific genes that were altered, they found that men with alterations to the BRCA1, BRCA2, or CDK12 genes improved most from the combination treatment, said study co-lead Karim Fizazi, M.D., Ph.D., of the Institut Gustave Roussy in France, during his presentation of the second cohort findings at the ASCO meeting.

About half of the participants in the second cohort had an alteration in at least one of the BRCA1, BRCA2, or CDK12 genes.

Weighing the risks of PARP inhibitor side effects

The enzalutamide–talazoparib combination is another option for people with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer that has these DNA damage repair alterations, “which is great,” said Dr. Karzai. But, she added, it’s critical for people to consider their quality of life and let their physicians know when they don’t feel well on the combination therapy.

“I think a lot of patients are afraid, especially when treated with drug combinations, that the doctor will take them off the drugs if they say anything about side effects,” Dr. Karzai said. “But I think it's really important that these patient outcomes are reported.”

PARP inhibitors can lead to a few serious side effects, explained Dr. Agarwal. These include a drop in blood cell counts, nausea and vomiting, and fatigue. Talazoparib, he noted, tends to cause substantial drops in red and white blood cell counts.

In the cohort of men whose tumors have a DNA repair gene alteration, about 10% of patients discontinued the combination treatment due to severe side effects of any kind, compared with 7% in the placebo group. The most common side effect was anemia, which occurred in nearly two-thirds of people receiving the drug combination—four times the number of people who developed anemia on enzalutamide alone.

The onset of anemia happens soon after starting treatment, Dr. Agarwal said. Typically, the oncologist will lower the dose, he explained, and at that point most patients are able to tolerate talazoparib well. In this cohort, he noted, only 4% of patients stopped receiving talazoparib due to anemia after initial dose reductions.

A broader approval remains uncertain

For now, FDA’s approval applies only to men whose metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer has DNA repair gene alterations. But patients whose tumors lacked alterations in DNA repair genes also had improved radiographic progression-free survival when treated with the combination compared with those treated with enzalutamide alone—although not nearly to the same extent, Dr. Agarwal noted.

Findings from this larger cohort in the trial were published June 4 in The Lancet.

So, an important next step, he said, is to understand why these tumors responded to the treatment despite lacking this critical genetic change. If they can identify specific biological characteristics of patients’ tumors that make them more likely to respond to the drug, it may be possible to expand the number of people who can benefit from the combination.

But for now, he said, “we need more data on safety and long-term overall survival benefit for all patients before we can recommend this combination [to everyone].”

The importance of genetic testing

Even as researchers try to iron out some of the unknowns about how best to use PARP inhibitors in people with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer, one thing is clear, Dr. Karzai emphasized.

“Everybody who's getting diagnosed with metastatic prostate cancer should talk to their doctors about getting genetic testing,” from tumor biopsies and through specialized tests that identify inherited mutations that may be present in the cells of the body and have been present since birth, she urged.

Dr. Agarwal agreed, explaining that many people being treated in smaller hospitals and cancer centers in their own communities are not getting tested for DNA repair gene alterations.

“Maybe because of a lack of resources, a lack of awareness, I don't know why, but a significant number of patients are not getting tested in the community,” he said.

Testing tumors for specific genetic changes is important for two reasons, Dr. Agarwal said. First, as more targeted drugs enter the market, it is increasingly possible to target the specific alterations that drive someone’s tumor. And second, some of these genetic alterations, known as germline alterations, are associated with familial predisposition to the disease, which may prompt screening in other family members.

“For metastatic prostate cancer, everybody agrees now that they need genomic testing of the tumor and germline,” Dr. Agarwal emphasized.