Study Identifies Potential Drug Target to Prevent Some Liver Cancers

, by NCI Staff

While new cases of most cancer types have dropped over the past decade, cases of the most common type of liver cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), are on the rise. Until recently, the main cause of HCC was hepatitis C virus infection. Although hepatitis C infection still causes many cases of HCC, the biggest contributor to the recent rise in cases is a condition called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which can progress to HCC.

In a new NCI-funded study, researchers have now identified a protein that could potentially be targeted to prevent both NASH and liver cancer: β2-spectrin.

Mice genetically modified to have no β2-spectrin in their livers did not develop NASH. And when the same mice were injected with chemicals that cause liver cancer, they developed fewer tumors than normal mice, Shuyun Rao, Ph.D., of George Washington University, and her colleagues reported December 15, 2021, in Science Translational Medicine.

The researchers also showed that they could treat normal mice with RNA molecules to reduce the amount of β2-spectrin in their livers. The RNA treatment prevented NASH in mice with healthy livers and reversed it in mice that had already developed the disease.

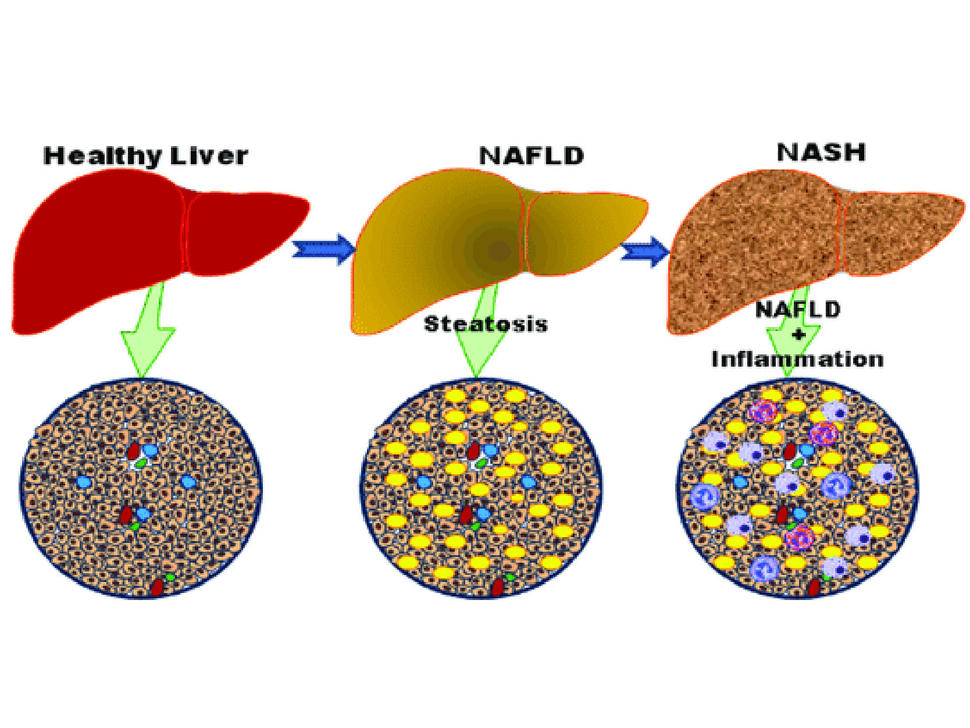

NASH arises from a milder liver condition, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

It's estimated that approximately 25% of adults worldwide have NAFLD, with rates varying by country. So if a safe β2-spectrin–blocking drug could be developed for use in humans, Dr. Rao said, “it could impact a lot of people.”

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and liver cancer

NAFLD is characterized by a buildup of fat in the liver. While people with NAFLD are at higher risk for other health problems, like cardiovascular disease, they don’t usually have severe liver problems.

“Initially, [NAFLD] is simply [an] accumulation of fat granules” in liver cells, explained Konstantin Salnikow, Ph.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Biology, who was not involved in the study. The condition can be controlled, or even reversed, with exercise and changes in a person's diet.

People with obesity are at higher risk for developing NAFLD. “Obesity is very common; a third of the world’s population has it,” said Lopa Mishra, M.D., the study’s senior investigator. And up to 90% of people with severe obesity are thought to have NAFLD.

In some cases, NAFLD progresses to a more severe condition called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH. In people with NASH, a buildup of fat causes liver inflammation and fibrosis, where scar tissue builds up in the liver. In some cases, NASH can result in liver cirrhosis, a more severe form of fibrosis.

And people with NASH often develop HCC. While it’s unclear what causes the transition, “up to 12% of people with NASH go on to develop [liver] cancer,” said Dr. Mishra.

Previous research, however, has suggested that a protein called TGF-β may be involved in this progression.

Studies have shown that TGF-β can suppress or promote the growth of many types of tumors, depending on the context, Dr. Salnikow said. For example, TGF-β prevents normal cells from becoming cancerous, but it promotes metastasis in cancer cells.

And TGF-β is known to promote fibrosis specifically. “It’s really the [severity of] fibrosis that predicts whether people with NASH will get cancer, and TGF-β plays a big role in fibrosis,” Dr. Mishra explained.

Dr. Mishra’s team decided to take a closer look at β2-spectrin because it organizes other proteins in the cellular communication pathway orchestrated by TGF-β. Indeed, an earlier study had found that cancer cells did not react to TGF-β activity as expected when β2-spectrin was absent.

Preventing fatty liver disease and liver cancer in mice

To investigate whether β2-spectrin promotes NAFLD or NASH, Dr. Rao and her team compared the livers of mice genetically engineered to lack the protein in their liver cells with those of normal mice.

The genetically modified mice did not seem to have impaired liver function despite the lack of β2-spectrin. “It was a big surprise,” said Dr. Mishra. Because β2-spectrin is found in almost all cells, researchers expected that it was crucial to cellular function.

The researchers went on to feed the mice one of two diets known to cause NAFLD and NASH: either a high-fat diet or a “western diet.” The western diet “has really been shown to reproduce human NASH” in mice, Dr. Mishra explained, and has “a different fat content, a different carbohydrate content” than the high-fat diet. While the western diet has a lower fat content than the high-fat diet, it has still been shown to cause NASH.

When fed either of these disease-causing diets, mice that lacked β2-spectrin in their livers did not develop NASH, whereas normal mice did. The genetically modified mice also gained less weight and had less body fat.

Losing β2-spectrin from their livers prevented NASH—but did it prevent liver cancer as well? To find out, the researchers needed to change their methods. Even in normal mice, HCC does not occur often enough to test whether removing β2-spectrin might prevent the cancer, explained Dr. Mishra.

To speed up the appearance of cancer in the mice, the researchers induced HCC with a chemical called DEN. Normal mice treated with DEN developed liver tumors, even when fed a standard diet.

Compared with normal mice, when mice lacking β2-spectrin in their livers were treated with DEN, they had far fewer liver tumors, and the tumors that did form were smaller on average.

The team was also able to prevent and treat NASH in normal mice by targeting β2-spectrin. To do so, they designed RNA molecules, known as small interfering RNAs (siRNA), that could reduce the amount of β2-spectrin produced in cells.

Mice treated with siRNA and then fed a high-fat diet gained less weight and had less body fat than mice that were untreated.

Furthermore, when mice that had already developed NASH after being fed a western diet were treated with the siRNA, their disease improved, as measured by lower fat and sugar levels in their blood.

To better assess whether their findings in mice might apply to humans, the researchers then turned to a different NASH model—a mix of human liver cells, immune cells, and support cells in a 3-D structure. This 3-D culture model, Dr. Salnikow explained, more closely mimics a human liver than just liver cells in culture.

The 3-D cultures treated with β2-spectrin siRNA had fewer of the characteristics typically seen in the liver of a person with NASH, including the activity of several genes, than 3-D cultures treated with a control treatment. It wasn’t possible for the researchers to tell whether cancer was prevented in this model, since the 3-D cultures don’t form tumors.

Bringing β2-spectrintargeted drugs to the clinic

A big question now is whether siRNA therapy for NASH could potentially be useful in humans. An siRNA drug is already approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat another form of liver disease called hepatic porphyria, Dr. Mishra noted.

“So, siRNA treatment strategies for the liver have been shown to work,” she said.

But there are still many steps to take before an siRNA drug like the one used in this study could be used to treat people with NAFLD or NASH, Dr. Mishra acknowledged. Although the mice used in their study “are looking absolutely fine,” she continued, further safety studies are needed before human studies can be launched.

And while targeting β2-spectrin with siRNA protected mice from chemically induced cancer, and also prevented and treated NAFLD in mice, it remains to be seen whether such a drug would prevent HCC in people with NASH, Dr. Rao and her colleagues wrote.

There are also open questions regarding the precise way that β2-spectrin promotes NAFLD. While Dr. Mishra’s team did identify some molecular mechanisms by which the protein drives fat accumulation in the liver, the question remains: “How does [β2-spectrin] actually turn on fatty liver disease?” asked Dr. Mishra.

The research team is also interested in identifying the specific parts of the β2-spectrin protein that are responsible for promoting NAFLD. This information could potentially be used to develop a small-molecule drug to block this activity of β2-spectrin.

This study may also have an impact on scientists’ understanding of NAFLD and liver cancer as a whole, according to Dr. Salnikow.

“This is the starting point of understanding the role of the TGF-β pathway” in the transition from NASH to liver cancer, he said. “This is only the tip of the iceberg.”