NIH scientists develop blood test to help improve liver cancer screening

- Posted:

240-760-6600

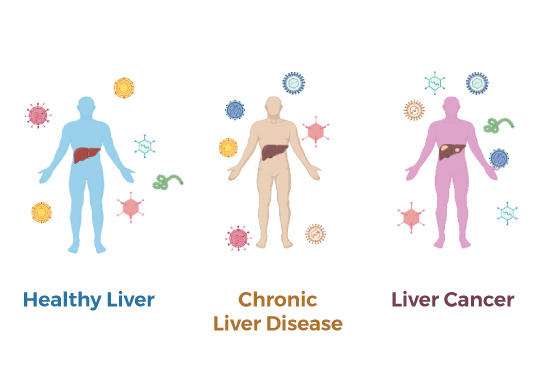

The blood test looks at past viral infections and can distinguish people who are likely to develop liver cancer from those with chronic liver disease and healthy livers.

Credit: Jinping Liu, Ph.D., University of Pennsylvania

Scientists have developed a new test that can help identify people who are likely to develop hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common form of liver cancer. The approach uses a simple blood test to check for the patient’s previous exposure to certain viruses.

A study of the new approach was led by researchers at the National Cancer Institute (NCI), part of the National Institutes of Health. The study also involved researchers from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and several academic centers. The findings were published June 10 in Cell.

“Together with existing screening tests, the new test could play an important role in screening people who are at risk for developing HCC. It could help doctors find and treat HCC early. The method is relatively simple and inexpensive, and it only requires a small blood sample,” said the study’s leader, Xin Wei Wang, Ph.D., co-leader of the NCI Center for Cancer Research (CCR) Liver Cancer Program.

Certain factors increase a person’s chances of developing HCC, such as infection with hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus or cirrhosis of the liver. People who have risk factors are recommended to get screened for HCC every six months with an ultrasound with or without a blood test for alpha-fetoprotein.

But not everyone with risk factors for HCC will develop the disease. Although screening can lead to earlier detection, most patients are diagnosed when the cancer is advanced and often incurable. However, HCC that is caught early has a much better chance of being cured.

“We need a better way to identify people who have the highest risk for HCC and who should get screened more frequently,” said Dr. Wang said, who is also part of NCI’s Translational Liver Cancer Consortium. Better early detection and surveillance approaches are particularly important because rates of HCC are rising in the United States.

“A main focus of the NCI CCR Liver Cancer Program is to develop new methods for early detection, diagnosis, and treatment, with the goal of improving outcomes for patients with HCC,” said Tim Greten, M.D., co-leader of the Liver Cancer Program and a collaborator of the study.

Many screening tests detect features of cancer cells. But those features can change over time, and not all cancer cells in a tumor have the same characteristics. The NCI team took a different approach: detecting features of the cancer’s environment rather than cancer cells themselves.

More research is providing evidence that cancer development is influenced by interactions between viruses and the immune system. The team reasoned that certain interactions between viruses and the immune system may raise the risk of developing HCC.

To explore that possibility, the scientists scanned people’s blood for “footprints” left behind by past viral infections. Because these footprints are left in antibodies, proteins made by the immune system, they also reflect how the immune system reacted to the infection. The mixture of footprints each person has creates a unique pattern, which the researchers called a viral exposure signature.

The team checked for the footprints of more than 1,000 different viruses in blood samples from around 900 people, including 150 who had HCC. They identified a specific viral exposure signature that could accurately distinguish people with HCC from people with chronic liver disease and healthy volunteers. This signature contained footprints from 61 different viruses.

The researchers then tested the signature on blood samples from 173 people with chronic liver disease who were part of a 20-year study. During that time, 44 of the participants developed HCC. Using blood samples taken when the cancer was diagnosed, the signature correctly identified those who developed HCC (area under the curve, AUC=0.98). Importantly, the signature also worked when the researchers used blood samples taken at the beginning of the study, up to 10 years before diagnosis (AUC=0.91).

The signature appeared to be far more accurate than an alpha-fetoprotein test (AUC=0.91 vs. 0.62). An AUC of 0.5 indicates that a test is no better than chance in identifying disease, whereas an AUC of 1.0 represents a test with perfect accuracy.

The scientists are continuing to study their approach and plan to test it in clinical trials. They are collaborating with Katherine McGlynn, Ph.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics to test the approach in a prospective surveillance study of people with risk factors for HCC.

It’s possible that viral infections—even ones that don’t cause cancer—may change the immune system in ways that influence the development of other cancers. For example, certain infections may lessen the immune system’s ability to keep cancer cells in check. NCI scientists are testing the viral exposure signature in a study of prostate cancer, and others are considering applying the approach to a screening study for ovarian, esophageal, liver, and breast cancer in Africa.

About the Center for Cancer Research (CCR): CCR comprises nearly 250 teams conducting basic, translational, and clinical research in the NCI intramural program—an environment supporting innovative science aimed at improving human health. CCR’s clinical program is housed at the NIH Clinical Center—the world’s largest hospital dedicated to clinical research. For more information about CCR and its programs, visit ccr.cancer.gov.

About the National Cancer Institute (NCI): NCI leads the National Cancer Program and NIH’s efforts to dramatically reduce the prevalence of cancer and improve the lives of cancer patients and their families, through research into prevention and cancer biology, the development of new interventions, and the training and mentoring of new researchers. For more information about cancer, please visit the NCI website at cancer.gov or call NCI’s contact center, the Cancer Information Service, at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237).

About the National Institutes of Health (NIH): NIH, the nation's medical research agency, includes 27 Institutes and Centers and is a component of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is the primary federal agency conducting and supporting basic, clinical, and translational medical research, and is investigating the causes, treatments, and cures for both common and rare diseases. For more information about NIH and its programs, visit nih.gov.