Study Suggests a Link between Stress and Cancer Coming Back

, by Nadia Jaber

For many cancer survivors, their worst nightmare is finding out that their cancer has come back. Even years after a seemingly successful treatment, cancer can start growing again, and scientists don’t know how this happens.

Now, a new study suggests that stress hormones may wake up dormant cancer cells that remain in the body after treatment. In experiments in mice, a stress hormone triggered a chain reaction in immune cells that prompted dormant cancer cells to wake up and form tumors again.

But if you are stressed, that doesn’t mean your cancer is going to come back, said the study’s lead researcher, Michela Perego, Ph.D., of The Wistar Institute Cancer Center. Several intermediate steps need to occur, Dr. Perego said, at least according to their studies in mice.

“There could be many different ways to wake dormant cells. We’ve shown one mechanism, but I’m very confident this is not the only one,” she added. The results of the new study were published December 2 in Science Translational Medicine.

While plenty of research has shown that stress can cause cancer to grow and spread in mice, studies haven’t shown a clear link between stress and cancer outcomes in people. But it’s difficult to study stress in people for several reasons, including challenges with defining and measuring stress.

Nevertheless, there could be many far-reaching effects of the new study findings, particularly in the realm of identifying new therapeutic leads, said Jeffrey Hildesheim, Ph.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Biology, who was not involved in the research.

“This study is like a gateway that will likely open up numerous other research directions into the effects of cancer therapies and stress on dormant tumor cells,” Dr. Hildesheim said. It could also spark research into the effects of nerves and the nervous system on tumor growth, he said.

Immune Cells Wake Up Dormant Cancer Cells

Some cancer treatments can push surviving cancer cells into hibernation. These dormant cells either stop growing or grow very slowly. Because there are so few of them, they’re impossible to find with standard tests, Dr. Perego explained. And they don’t usually cause any issues—unless they start growing again.

“We don’t know exactly what triggers them to come back. Why in that moment?” she said.

Dr. Perego studies how certain immune cells help cancer grow and spread. So, she wondered, could immune cells wake up dormant cancer cells?

To find out, her team created dormant cancer cells in the laboratory by genetically engineering lung cancer cells, or by treating lung, ovarian, and breast cancer cells with a common chemotherapy drug. Both kinds of dormant cancer cells survived but didn’t grow.

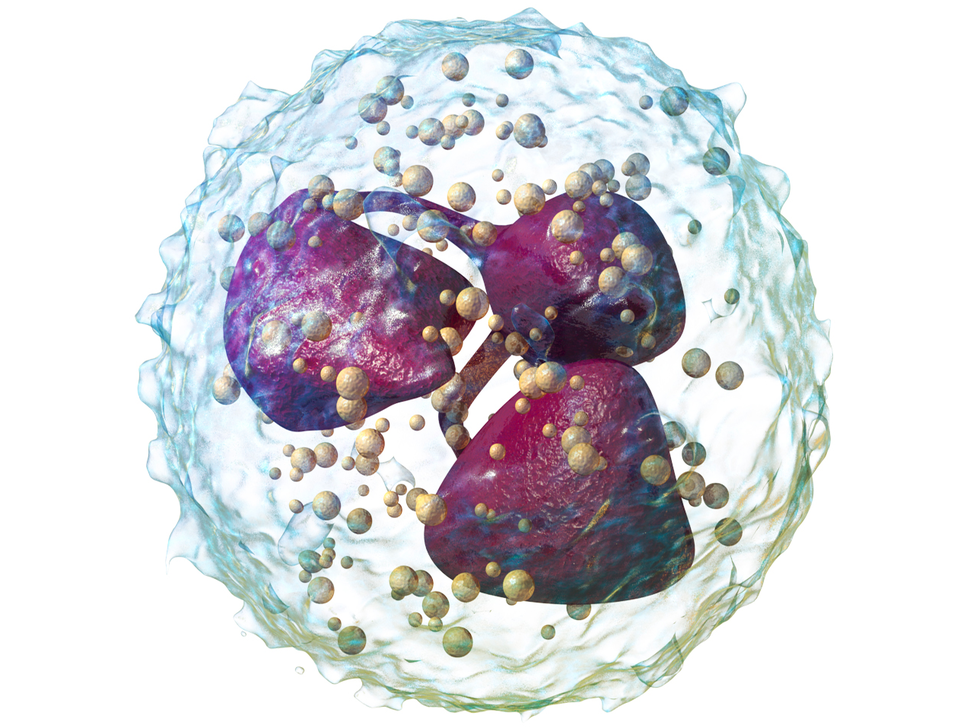

In lab dishes, dormant cells didn’t grow when mixed with B cells or T cells, two kinds of immune cells. But they started growing again when mixed with so-called “pro-tumor” neutrophils.

Neutrophils, a kind of white blood cell, are part of the body’s first line of defense against infections. But tumors can turn neutrophils into bad actors, coaxing them into helping the tumor grow and spread.

When the researchers transplanted dormant lung cancer cells into mice that lacked an immune system, these cells didn’t form tumors. But if the dormant cancer cells were transplanted along with pro-tumor neutrophils, most of the mice developed lung tumors.

Stress Hormones Alter Neutrophils

With that finding, Dr. Perego and her colleagues faced a key question: What turns neutrophils rogue if there are no tumors left in a patient’s body? Because some studies have linked chronic stress to cancer progression, the scientists explored the effects of stress on neutrophils.

Stress hormones like adrenaline and norepinephrine set off a chain reaction involving neutrophils and dormant cancer cells, the researchers found. In lab dishes, stress hormones caused neutrophils to spit out a protein duo known as S100A8/A9. These proteins made neutrophils produce certain lipids that, in turn, awakened dormant lung cancer cells.

A mixture of norepinephrine and neutrophils also woke up human cancer cells made dormant from chemotherapy.

What’s happening is “a type of cascade,” Dr. Perego said. “One component of this cascade alone doesn’t work. Neutrophils alone, S100A8/A9 alone, and stress hormones alone don’t work” to wake up dormant cells, she explained. “But when you have this chain of events…it reawakens dormant cells.”

Preventing Recurrences in Stressed Out Mice

The researchers next explored whether the same cascade occurred in mice that were stressed from being confined for a few hours a day.

Stressed mice had more neutrophils in their lungs and spleens than unstressed mice, the scientists found. The stressed mice also had more S100 proteins in their blood. Dormant lung cancer cells formed tumors in stressed mice but not in unstressed mice.

However, when stressed mice were treated with a beta blocker, a blood pressure medicine that blocks stress hormones, dormant cancer cells couldn’t form tumors. The researchers saw similar effects when mice were treated with tasquinimod, a drug that blocks the activity of S100 proteins and has been tested in people with prostate cancer.

The team also looked at blood samples from 80 people who had had surgery to remove their lung tumors. For 17 patients, the cancer came back (recurred) within 3 years of their surgery. For the others, the cancer came back more than 3 years later or didn’t come back at all.

Earlier recurrence was more likely among patients with high levels of S100 proteins or norepinephrine in their blood than among those with low levels. Similarly, a 2019 study linked levels of S100 proteins in melanoma tumors with cancer metastasis and how long patients lived. However, a recent analysis of several studies found that the use of beta blockers wasn’t linked with longer survival of cancer patients.

Opening the Floodgates for Research

Researchers have suspected that there might be a link between stress and cancer for some time. But “the mechanism behind that link remains somewhat elusive,” Dr. Hildesheim said. This study “makes a significant contribution” by identifying various components that might, in part, underlie that connection, he noted.

What’s more, this same mechanism could be contributing to cancer growth and treatment resistance in other ways, Dr. Hildesheim said. “The nervous system could be impacting [cancer] from multiple angles,” he added.

A 2019 study, for example, showed that stress hormones can increase the number of pro-tumor immune cells in tumors. That could mean that stress not only wakes up dormant tumor cells but also provides the right environment for them to grow, Dr. Hildesheim explained.

“It’s the worst of both worlds,” he said.

But, like Dr. Perego, he thinks it’s something that could be addressed by combining treatment approaches. Scientists are working to develop drugs that block the activity of or kill certain kinds of dormant cells called senescent cells. Finding ways to target senescent and dormant cells are two focuses of a recent partnership between NCI and Cancer Research UK.

Chemotherapy, radiation, and targeted therapy can all turn cancer cells into senescent cells. When combined with these traditional treatments, it’s possible that drugs that target senescent cells may prevent cancer from coming back, Dr. Hildesheim said.