Study Examines Whether Blood Test Can Identify Early Cancers

, by NCI Staff

In the first study of its kind, a blood test combined with imaging tests detected tumors—some at an early stage—in women without a history of cancer or any symptoms.

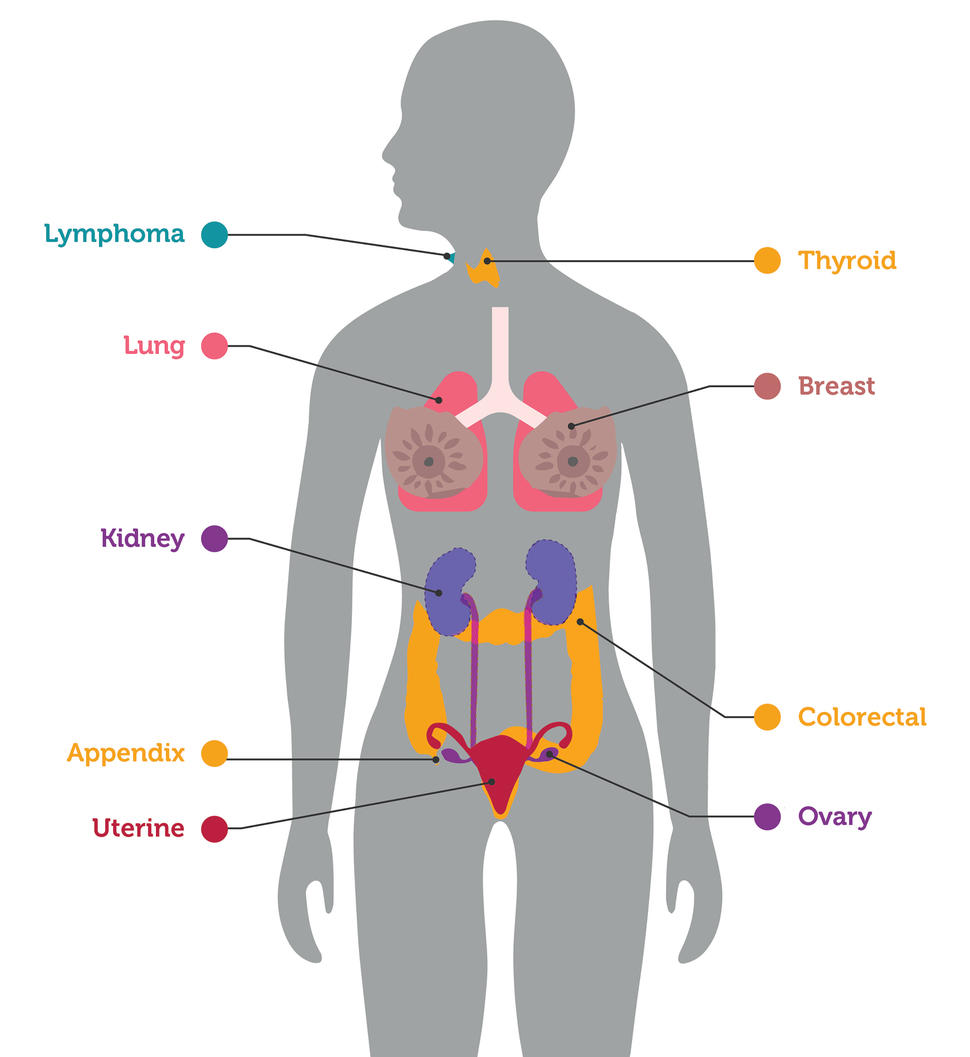

The blood test identified breast, lung, and colorectal cancers, for which there are recommended screening tests. But it also identified seven other cancer types for which no screening tests exist.

Researchers led by Nickolas Papadopoulos, Ph.D., of Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, designed the study to see whether it was possible to use such a blood test to detect cancers before symptoms developed. They also wanted to make sure the testing process did not cause participants distress or lead to many unnecessary diagnostic procedures.

The study was not designed to determine whether finding and treating the cancers identified by the test reduced the number of deaths from cancer among participants.

The findings were presented at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) annual meeting and published in Science on April 28.

Although it’s counterintuitive, detecting a cancer early does not necessarily reduce the likelihood of dying from cancer, explained David Ransohoff, M.D., of UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, who was not involved with the study. Some screening may actually cause more harm than good, Dr. Ransohoff said.

Such potential harms can include the identification of very early-stage cancers that would not have affected someone during their lifetime, a phenomenon known as overdiagnosis, or that may lead to unnecessary invasive procedures or treatments—known as overtreatment.

In the study, use of the blood test, along with standard imaging procedures, led to the detection of 26 cancers among approximately 10,000 study participants. The test also provided some false-positive findings, mistakenly indicating some women had cancer when further testing showed that they did not.

However, only 38 women who received false-positive test results ended up having additional follow-up tests after the initial imaging, and most of these women had noninvasive or minimally invasive testing.

A larger study that specifically examines whether such a test could reduce deaths from cancer is needed before the test could potentially be adopted as an everyday approach for cancer screening, explained Sudhir Srivastava, Ph.D., M.P.H., of NCI's Division of Cancer Prevention.

“But this is a landmark study in terms of its conception, design, and application. This likely shows how [cancer] screening will happen in the future,” he said.

Two-Way Communication with Tumors

All tumors, no matter how small, maintain a connection to the bloodstream to pull in needed nutrients. This communication goes two ways, with proteins and genetic material spilling from the tumor into the circulation.

Researchers have been taking advantage of this tumor-to-bloodstream spillover by developing what have come to be called liquid biopsies. These tests can use blood (or other bodily fluids) to noninvasively detect cancer or track the status of cancer in somebody undergoing treatment.

And “screening is top of the heap in terms of potential impact [of these tests]. It's also the greatest challenge,” said David Huntsman, M.D., of the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, speaking at the AACR meeting. “Screening requires high sensitivity and near-perfect specificity.” That is, a screening test must be very good at finding cancer if it exists. And it shouldn’t identify people as having cancer when they don’t.

Dr. Papadopoulos and his colleagues have been developing their test, called CancerSEEK, for over a decade. The version used in the study detects alterations in 16 genes associated with cancer, in pieces of tumor DNA circulating in the bloodstream. It also measures the blood levels of 9 proteins overproduced by some cancer types. In 2018, the team published results from a study where another version of the test correctly identified most women with endometrial cancer and one-third of women with ovarian cancer.

But the women in that study were already known to have cancer. Such cancers are likely to be larger, more advanced, and easier to pick up with a blood test than undiagnosed, early-stage cancers, explained Dr. Papadopoulos.

Reducing False Alarms

To see if CancerSEEK could find small, previously undetected cancers, the researchers enrolled 10,006 women aged 65 to 75 with no known cancer in their study, called DETECT-A. They included only women to increase the likelihood of picking up ovarian cancer, which is often not found until it’s already at an advanced stage and for which there is no approved screening test.

Several measures were taken during the trial to decrease the number of women experiencing stress or potentially unnecessary diagnostic procedures.

For example, women were told when enrolling in the trial that they might be contacted randomly for a second blood test regardless of their initial results. This reduced the chance of causing fear from a callback to confirm a positive result on the first test. Genetic counselors were available to participants at all stages of the trial, and women were strongly encouraged to receive standard screening tests, in compliance with recommendations, during the follow-up period.

If the initial blood test for a woman picked up high levels of one of the genes or proteins indicative of cancer, they were invited back for a second test. If the second test came back positive, and if other health conditions could not account for the test results, they were referred for a whole-body PET‒CT scan. Only participants with a finding on the PET‒CT imaging that was suspicious for cancer were referred to an oncologist for further diagnostic testing.

All these steps “were important in terms of minimizing overdiagnosis,” said Dr. Srivastava.

To Complement, Not Replace

Out of 10,006 women who enrolled in the study, 26 eventually received a diagnosis of cancer first detected by the blood test.

| Women Who Enrolled in the Study | 10,006 |

| Women Who Had an Initial Blood Test Suggestive of Cancer | 490 |

| Women Who Had PET‒CT Imaging Based on Results from Second Blood Test | 127 |

| Women Referred for Further Diagnostic Testing after Imaging | 64 |

| Women Found Not to Have Cancer after Additional Noninvasive Testing | 16 |

| Women Found Not to Have Cancer after Additional Minimally Invasive Testing | 19 |

| Women Who Had Surgery for a Precancerous Mass | 3 |

| Women Found to Have Cancer First Detected by the Blood Test | 26 |

Of those 26 cancers, 14 were in organs such as the ovaries, kidney, and lymphatic system, for which no approved screening tests exist. Nine of these were cancers that had not yet spread from their original location.

Such cancers “have a higher chance of successful treatment,” compared with cancers that have already spread widely, said Dr. Papadopoulos.

During the trial, 24 additional cancers not identified by the blood test were picked up by standard screening: 20 breast cancers, 3 lung cancers, and 1 colorectal cancer. Of the 24 cancers, 22 were early-stage cancers.

In addition, 46 women in the study received a diagnosis of cancer that was detected neither by the blood test nor standard screening. Most of these 46 diagnoses occurred after a woman reported symptoms.

"So, can such a [blood] test be performed safely, without triggering a large number of futile, invasive follow-up tests based on the test results? Yes," said Dr. Papadopoulos.

Another presentation during the same session at AACR highlighted an additional liquid biopsy test under development that successfully detected cancer in people already undergoing testing for a suspected cancer.

“Both studies have shown that we're moving in the right direction. But we're not there,” said Dr. Huntsman. These tests need to be shown to reduce the chance of dying from cancer “to get us to the point where these tests could be adopted.”

The CancerSEEK team is planning a larger study with the goal of applying for FDA approval, Dr. Papadopoulos said. That study will be similar in design to DETECT-A, but include men and a wider range of age groups. It will also use an updated version of the CancerSEEK test.

But FDA approval would be only the first step for such a test, Dr. Ransohoff cautioned. “The high bar is going to be set by the US Preventive Services Task Force and ... payers like the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. And then by doctors and patients,” he said. The general rule, he added, is that a screening test will not get this level of support until it shows it provides more benefit than harm.

“The reason that high bar is there is because, with screening, we're interfering in the lives of healthy people. So, we don't do it unless we're really sure that there's a benefit,” Dr. Ransohoff continued. “And the widely accepted definition of what benefit means is a mortality reduction from cancer. [Currently], we don’t know if there is one for the cancers targeted by these blood tests.”

There's a substantial amount of ongoing research into using a blood test to screen for multiple cancers, Dr. Srivastava noted. "While challenges remain in using these tests in people without symptoms, the two studies presented at AACR are groundbreaking, and offer hope for the eventual early detection of cancers that currently don't have a recommended screening test,” he said.

The hope for such blood tests is that they could eventually reduce the number of deaths from cancer types such as ovarian or liver cancer, which are uncommon but deadly when found late, said Dr. Papadopoulos. But it’s unlikely that a blood test would replace the cancer screening methods currently used in the clinic, he added.

“Any blood test needs to complement and add to standard-of-care screening [for breast, colorectal, and lung cancer], because standard-of-care screening works.”