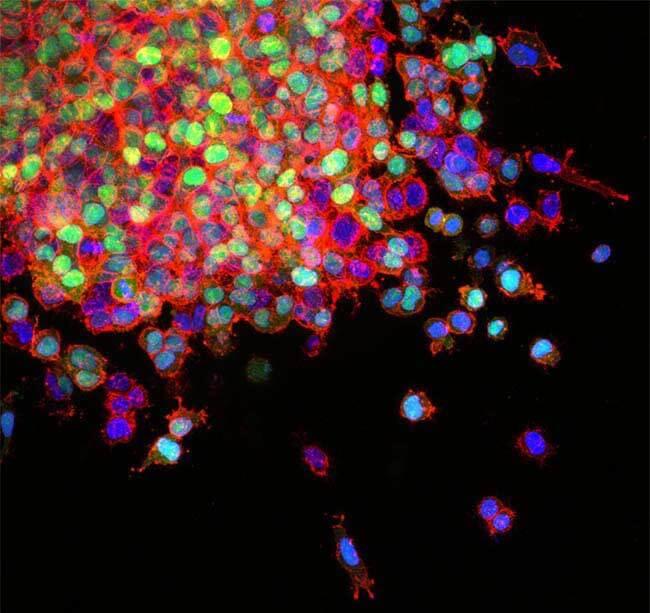

Cellular Invasion and Migration

A fundamental trait of metastatic tumor cells is the ability to migrate and invade into the surrounding tissue. Supported research focuses on cell intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms that enhance metastatic capability including cell invasion and motility as single cells or as clusters, phenotypic changes and the impact of the tumor microenvironment on the acquisition of metastatic properties.

Key research areas include:

- Basic mechanisms of single cell and collective motility and the impact of local or systemic changes on driving invasion and motility

- Altered gene and protein expression, changes in cell polarity, and phenotypic plasticity (e.g., epithelial-mesenchymal transition, mesenchymal-epithelial transition, etc.) that facilitate invasion and migration

- Dysregulated expression of molecular species, such as gene variants, RNA types (e.g., miRNA, lncRNA, noncoding RNAs), and dysregulated protein post-translational modifications that regulate or promote invasion and migration

- Altered protease activity and remodeling of extracellular matrix, loss of cell-cell or cell-matrix adhesion, and modulated cytoskeletal dynamics underlying invasion and migration

- The contribution of tumor, stromal and immune-related cells that enhance cell invasion and motility

- Mechanisms of perineural invasion (i.e., the process by which cancer cells grow and migrate along nerve fibers)

Research into mechanisms of motility, particularly in clusters, provides insight into how cancer cells can survive during metastatic spread.

Intravasation and Extravasation

Metastatic cells leaving the primary tumor enter blood or lymphatic vessels (intravasate) and subsequently exit (extravasate) at distal metastasis supporting sites or organs. Supported research focuses on mechanisms and consequences of tumor cell interactions with blood or lymphatic vessels, lymph nodes, and interactions with immune cells or blood components during circulation.

Key research areas include:

- Cell and vascular adhesion molecules

- Angiogenesis, vasculogenesis, and vascular permeability

- Mechanisms associated with mechanical, physiological, or cellular stresses that impact intravasation/extravasation processes

- Mechanisms and consequences of interactions between tumor cells and immune cells and immune cell-assisted intravasation, survival, and extravasation

- Role of coagulation components such as platelets that aid intravasation/extravasation processes

Recent studies have revealed that clusters of tumor cells entering the circulation exhibit a substantially greater ability to survive and colonize distal organs compared to single disseminated tumor cells.

Early Metastatic Dissemination

Metastasis-competent tumor cells may arise in the very early stages of tumor development— often before palpable primary tumors are detected—and enter the circulation. These earliest circulating disseminated cancer cells can have phenotypically distinct gene expression and metabolic profiles, and enhanced metastatic potential compared to disseminated cells derived from later stage tumors. Supported research focuses on identification, characterization, and behavior of circulating/disseminated tumor cells and the characteristics and circumstances by which they arise from the primary tumor.

Key research areas include:

- Identification of circulating tumor cells in blood or lymph, including the application of technological advances such as barcoding technologies, single cell sequencing, and intravital microscopy

- Phenotypic plasticity, characterization and biology of circulating tumor cells

- Mechanisms that facilitate tumor cell dissemination and survival in the circulation

- Models of early metastatic dissemination, including use of microfluidic platforms for metastasis research

- Models of metastatic dissemination via the nervous system

- Cancer stem/initiating cells and their role in metastasis

Research into early metastatic dissemination may improve both early detection and identify unique intervention strategies for potentially more aggressive metastasis.

The Metastatic Niche and Colonization

Colonization —the rate-limiting step in metastasis— is the ability of disseminated tumor cells not only to survive, but also to grow into metastatic lesions in secondary tissues or organs. How disseminated tumor cells ultimately home to or end up in such locations is determined by multiple factors. The sites for future metastatic colonization are often pre-conditioned by factors arising from the primary tumor and the homing or recruitment of distinct non-tumor cell types. Supported research focuses on the nature of these pre-conditioning factors, the contribution of the metastatic microenvironment in promoting colonization, mechanisms that promote metastatic outgrowth, and mechanisms associated with resistance to therapies.

Key research areas include:

- Cell-cell interactions, including the role of chemokines, cytokines, and other cell and matrix associated factors in metastatic niche conditioning

- Mechanisms by which extracellular vesicles or exosomes, or host systemic effects influence the pre-metastatic and metastatic niche formation

- Mechanisms of organotropism and homing including the influence of host pathology and physiology on these processes

- Stromal, neural, and immune cell profiling and cell function (e.g., colonization and proliferation) in the metastatic niche

- Proteases, adhesion receptors and remodeling of extracellular matrix in metastatic sites

- Mechanisms identifying how metastatic cells resist therapies

- Mechanisms and functional biology by which metastatic cells evade the immune system

- Interactions between cancer cells and their microenvironmental components within the metastatic niche

Research into understanding the metastatic niche and colonization highlights how metastasis is a whole-body physiology challenge, with complex communication between the metastatic niche and primary tumor. Recent work has found that skeletal muscle-derived reactive oxygen species incapacitate disseminated tumor cells explaining why this tissue is a rare site for metastasis.

Metastatic Dormancy

Disseminated tumors cells arriving at primed metastatic sites often persist in a dormant state for unspecified periods of time (months to decades). Critical areas of research include understanding how tumor cells maintain the dormant state; how tumor cells are instructed to emerge from the dormant state; and how tumor cells can be kept in a dormant state preventing their development into macrometastatic lesions.

Key research areas include:

- Tumor cell intrinsic dormancy programs and signatures

- Tumor cell extrinsic programs characterizing the influence of the metastatic microenvironment, including stromal, immune and nerve cells, on dormancy

- Angiogenic dormancy

- Cell intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms and factors that regulate emergence from dormancy

- Development of experimental models of dormancy

Research into understanding mechanisms that promote and/or override dormancy has potential to facilitate the identification of potential therapeutic opportunities to treat metastatic disease.

Systems Biology and Systemic Effects of Cancer

Cancer is a systemic disease that affects the physiological function of multiple organs. Altered function of an organ can occur in the absence of any detectable metastatic cancer cells within that organ and is known as a systemic effect. Cancer cachexia, a complex syndrome defined by progressive muscle and/or fat loss, is one such systemic effect that dramatically impacts a patient. Because metastasis and cancer cachexia are often intertwined, it is critical to understand their full impact on patients. Systems biology for metastasis or cancer cachexia can incorporate computational or mathematical models and/or incorporate a whole-body perspective investigating multiple biological systems such as immune, vascular, lymphatic, nervous systems and their interactions across biological and time scales.

- Computational or mathematical models to predict metastatic disease or describe the molecular mechanisms underlying cancer metastasis

- Generation and analysis of large-scale molecular datasets using systems biology approaches in metastasis

- Cancer cachexia and disease progression and metastasis

- Systemic effects that contribute to cancer cachexia or metastasis

- Emergent processes associated with metastasis

- Interactions between multiple physiological systems (e.g., immune, vascular, lymphatic and nervous systems) contributing to metastasis progression and colonization

Emerging research aims to mechanistically understand how cancers induce perturbations in physiological systems, such as the neuro-immune systems, that impact patient sequelae and create conditions permissive to metastatic growth.