Studying Early Detection for Men at High Risk

Men with certain inherited genetic traits are at increased risk for developing prostate cancer. Examples of such traits include inherited BRCA gene mutations and Lynch syndrome. No clear guidelines exist for when or how—or if—to screen men at high genetic risk for prostate cancer.

NCI researchers are using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the prostate in men at high risk of developing prostate cancer to learn more about how often and how early these cancers occur. They’re also testing whether regular scans in such men can detect cancers early, before they spread elsewhere in the body (metastasize).

Diagnosing Prostate Cancer

Improving biopsies for prostate cancer

Traditionally, prostate cancer has been diagnosed using needles inserted into the prostate gland in several places under the guidance of transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) imaging to collect samples of tissue. This approach is called systematic biopsy.

However, ultrasound does not generally show the location of cancer within the prostate. It is mainly used to make sure the biopsy needles go into the gland safely. Therefore, biopsy samples using ultrasound guidance can miss cancer altogether. Or they may identify low-grade cancer while missing areas of high-grade, potentially more aggressive cancer, particularly in Black men.

Some doctors, concerned that a systematic biopsy showing only low-grade cancer could have missed a high-grade cancer, may suggest surgery or radiation. However, in some cases these treatments will be for a cancer that may have never caused a problem, which is considered overtreatment.

Using MRI and ultrasound. Scientists at NCI have developed a procedure that combines magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with TRUS for more accurate prostate biopsies. MRI can locate potential areas of cancer within the gland but is not practical for real-time imaging to guide a prostate biopsy. The procedure, known as MRI-targeted biopsy, uses computers to fuse an MRI image with an ultrasound image. This lets doctors use ultrasound guidance to take biopsy samples of areas of possible cancer seen on MRI.

NCI researchers have found that combining MRI-targeted biopsy with systematic biopsy can increase the detection of high-grade prostate cancers while decreasing detection of low-grade cancers that are unlikely to progress.

Testing machine learning. Researchers are testing the use of machine learning, also called artificial intelligence (AI), to better recognize suspicious areas in a prostate MRI that should be biopsied. AI is also being developed to help pathologists who aren't prostate cancer experts accurately assess prostate cancer grade. Cancer grade is the most important factor in determining the need for treatment versus active surveillance.

Finding small amounts of prostate cancer using imaging and PSMA

NCI-supported researchers are developing new imaging techniques to improve the diagnosis of recurrent prostate cancer. A protein called prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is found in large amounts—and almost exclusively—on both cancerous and noncancerous prostate cells. By fusing a molecule that binds to PSMA to a compound used in PET imaging, scientists have been able to see tiny deposits of prostate cancer that are too small to be detected by regular imaging.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved two such compounds for use in PSMA-PET imaging of men with prostate cancer. These approvals are for men whose cancer may have spread to other parts of the body but is still considered curable, either with surgery or other treatments.

The ability to detect very small amounts of metastatic prostate cancer could help doctors and patients make better-informed treatment decisions. For example, if metastatic cancer is found when a man is first diagnosed, he may choose an alternative treatment to surgery because the cancer has already spread. Or doctors may be able to treat cancer recurrence—either in the prostate or metastatic disease—earlier, which may lead to better survival. Studies are being done to determine if such early detection can improve outcomes.

NCI researchers are testing whether PSMA-PET imaging can also identify men who are at high risk of their cancer recurring. Such imaging may eventually be able to help predict who needs more aggressive treatment—such as radiation therapy in addition to surgery—after diagnosis.

Research teams are also looking at:

- whether certain patterns seen on PSMA-PET tests taken over time may indicate an increased risk of recurrence after initial treatment

- how small metastases discovered with PSMA change over time, with or without treatment

New Prostate Cancer Treatments

Standard treatments for prostate cancer that has not spread elsewhere in the body are surgery or radiation therapy, with or without hormone therapy.

Active surveillance is also an option for men who have a low risk of their cancer spreading. This means monitoring the cancer with regular biopsies and other tests, and holding off on treatment unless there is evidence of progression. Rates of active surveillance more than doubled between 2014 and 2021, to almost 60% of US men diagnosed with low-risk prostate cancer.

Hormone therapy for prostate cancer

Over the last decade, several new approaches to hormone therapy for advanced or metastatic prostate cancer have been approved for clinical use.

Many prostate cancers that originally respond to treatment with standard hormone therapy become resistant over time, resulting in castrate-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). Four newer drugs have been shown to extend survival in some groups of men with CRPC. All inhibit the action of hormones that drive CRPC:

These drugs are now also used in some people whose prostate cancer still responds to standard hormone therapies but has spread elsewhere in the body (metastasized).

Scientists are continuing to study novel treatments and drugs, along with new combinations of existing treatments, in men with metastatic and castrate-resistant prostate cancer.

Hormone therapy for biochemically recurrent prostate cancer

A biochemical recurrence is a rise in the blood level of PSA in people with prostate cancer after treatment with surgery or radiation. In 2023, the FDA approved enzalutamide, given alone or with another drug called leuprolide, for some men who have a biochemical recurrence and are at high risk of their cancer spreading but don’t have signs on regular imaging that their cancer has come back.

Use of this drug combination can improve how long these men live without their cancer spreading. But it’s not yet known if using the drugs in this manner improves how long people live overall. Researchers are trying to determine which patients will benefit most from these types of treatments.

PARP inhibitors for prostate cancer

A PARP inhibitor is a substance that blocks an enzyme in cells called PARP. PARP helps repair DNA when it becomes damaged. Some prostate tumors have genetic changes that limit their ability to repair DNA damage. These tumors may be sensitive to treatment with PARP inhibitors. Some people also inherit genetic factors that limit their body’s ability to repair DNA damage. Prostate tumors in such people can also be treated with PARP inhibitors.

Two PARP inhibitors, olaparib (Lynparza) and rucaparib (Rubraca), have been approved for use alone in some men whose prostate cancer has such genetic changes and has metastasized, and whose disease has stopped responding to standard hormone treatments alone.

Ongoing studies are looking at combining PARP inhibitors with hormone therapies. Since 2023, the FDA has approved three such combinations for some men with metastatic prostate cancer:

- the hormone therapy enzalutamide (Xtandi) with the PARP inhibitor, talazoparib (Talzenna)

- the hormone therapy abiraterone (Zytiga) with the PARP inhibitor olaparib (Lynparza)

- the hormone therapy abiraterone with the PARP inhibitor niraparib (Akeega)

Immunotherapy: vaccines for prostate cancer

Immunotherapies are treatments that harness the power of the immune system to fight cancer. These treatments can either help the immune system attack the cancer directly or stimulate the immune system in a more general way.

Vaccines and checkpoint inhibitors are two types of immunotherapy being tested in prostate cancer. Treatment vaccines are injections that stimulate the immune system to recognize and attack a tumor.

One type of treatment vaccine called sipuleucel-T (Provenge) is approved for men with few or no symptoms from metastatic CRPC.

Immunotherapy: checkpoint inhibitors for prostate cancer

An immune checkpoint inhibitor is a type of drug that blocks proteins on immune cells, making the immune system more effective at killing cancer cells.

Two checkpoint inhibitors, pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and dostarlimab (Jemperli) have been approved for the treatment of tumors, including prostate cancers, that have specific genetic features. Pembrolizumab has also been approved for any tumor that has metastasized and has a high number of genetic mutations.

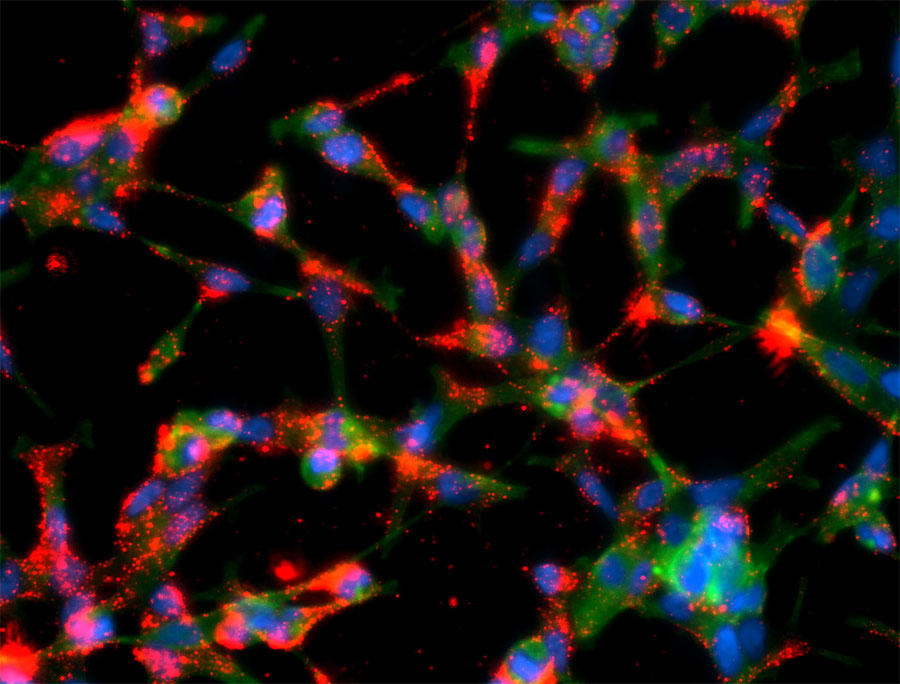

But relatively few prostate cancers have these features, and prostate cancer in general has largely been resistant to treatment with checkpoint inhibitors and other immunotherapies, such as CAR T-cell therapy.

Research is ongoing to find ways to help the immune system recognize prostate tumors and help immune cells penetrate prostate tumor tissue. Studies are looking at whether combinations of immunotherapy drugs, or immunotherapy drugs given with other types of treatment, may be more effective in treating prostate cancer than single immunotherapies alone.

PSMA-targeted radiation therapy

Scientists have developed targeted therapies based on PSMA, the same protein that is used for imaging prostate cancer. For treatment, the molecule that targets PSMA is chemically linked to a radioactive substance. This new compound can potentially find, bind to, and kill prostate cancer cells throughout the body.

In a recent clinical trial, men with a type of advanced prostate cancer who received a PSMA-targeting drug lived longer than those who received standard therapies. This trial led to FDA approval of the drug, Lu177-PSMA-617 (Pluvicto), to treat some people with metastatic prostate cancer who had previously received chemotherapy.

An ongoing study is testing the use of Lu177-PSMA-617 in some people with metastatic prostate cancer who haven't yet received chemotherapy. Other clinical trials are testing PSMA-targeting drugs in patients with earlier stages of prostate cancer, and in combination with other treatments, including targeted therapies like PARP inhibitors and immunotherapy.

Personalized clinical trials for prostate cancer

Research is uncovering more information about the genetic changes that happen as prostate cancers develop and progress. Although early-stage prostate cancer has relatively few genetic changes compared with other types of cancer, researchers have learned that metastatic prostate cancers usually accumulate more changes as they spread through the body.

These changes may make men with metastatic prostate cancers candidates for what are called “basket” clinical trials of new drugs. Such trials enroll participants based on the changes found in their cancer, not where in the body the cancer arose. In the NCI-MATCH trial, a high percentage of enrolled men with advanced prostate cancer had genetic changes that could potentially be targeted with investigational drugs.

NCI-Supported Research Programs

Many NCI-funded researchers working at the National Institutes of Health campus, as well as across the United States and world, are seeking ways to address prostate cancer more effectively. Some of this research is basic, exploring questions as diverse as the biological underpinnings of cancer and the social factors that affect cancer risk. And some is more clinical, seeking to translate basic information into improving patient outcomes. The programs listed below are a small sampling of NCI’s research efforts in prostate cancer.

- The Cancer Biomarkers Research Group promotes research on cancer biomarkers and manages the Early Detection Research Network (EDRN). EDRN is a network of NCI-funded institutions that are collaborating to discover and validate early detection biomarkers.

- Within the Center for Cancer Research, the Prostate Cancer Multidisciplinary Clinic (PCMC) provides comprehensive consultations on diagnosis and treatment options to people with newly-diagnosed prostate cancer.

- The Prostate Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (Prostate SPOREs) are designed to quickly move basic scientific findings into clinical settings. The Prostate SPOREs support the development of new therapies and technologies and studies to better understand how to prevent, monitor, and treat prostate cancer.

- The NCI Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET) focuses on using modeling to improve our understanding of which men are most likely to benefit from PSA-based screening. CISNET also studies treatment strategies for prostate cancer and approaches for reducing prostate cancer disparities.

- The NCI Genitourinary Malignancies Center of Excellence (GUM-COE) brings together scientists studying genitourinary cancers (GU) from across NCI’s Center for Cancer Research and the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, as well as investigators who study GU malignancies in other institutes of NIH. The goal is to provide a centralized resource and infrastructure to accelerate the discovery, development, and delivery of interventions for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of these cancers.

- The Research on Prostate Cancer in Men with African Ancestry (RESPOND) study is the largest-ever coordinated research effort to study biological and non-biological factors associated with aggressive prostate cancer in African American men. The study, launched by NCI and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities in partnership with the Prostate Cancer Foundation, is looking at the environmental and genetic factors related to the aggressiveness of prostate cancer in African American men to better understand why they disproportionally experience aggressive disease.

Clinical Trials

NCI funds and oversees both early- and late-phase clinical trials to develop new treatments and improve patient care. Trials are available for prostate cancer prevention, screening, and treatment.

Prostate Cancer Research Results

The following are some of our latest news articles on prostate cancer research:

View the full list of Prostate Cancer Research Results and Study Updates.