Rusfertide Nearly Eliminates Need for Phlebotomies to Treat Polycythemia Vera

, by Shana Spindler

For people with polycythemia vera, treatment with the drug rusfertide appears to substantially reduce their reliance on blood draws to avoid serious health problems. That’s according to results of the first-ever clinical trial to test a drug like rusfertide—which blocks the production of iron-rich blood cells—in people with this chronic blood cancer.

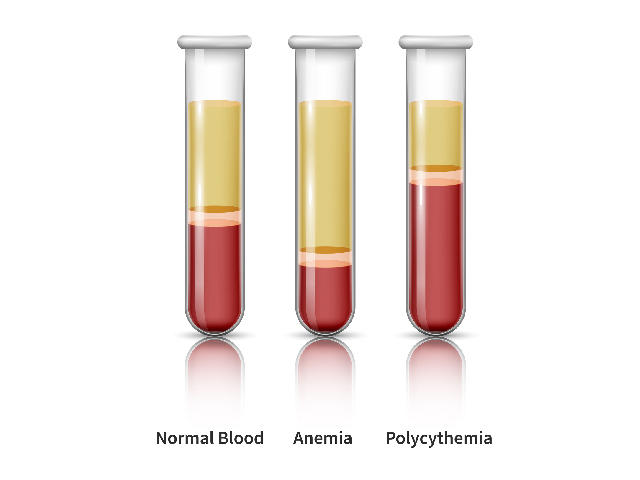

In people with polycythemia vera, the bone marrow makes too many red blood cells. This overproduction of cells thickens the blood and, if left untreated, increases the risk for blood clots, heart attack, and stroke.

For decades, the main treatment for polycythemia vera has been regular blood draws, or phlebotomy, to remove excess red blood cells. But this rudimentary treatment has downsides, including debilitating fatigue and brain fog. The need to make regular trips to a doctor’s office for the procedure is also time consuming and affects people’s quality of life.

“Basically, in a way, we still treat patients with polycythemia vera by bloodletting,” said Marina Kremyanskaya, M.D., Ph.D., of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City, who led the study.

So Dr. Kremyanskaya began studying treatments that specifically suppress red blood cell formation—calling it a “chemical phlebotomy.” Several of these drugs, known as hepcidin mimetics, are currently being studied in clinical trials. Rusfertide is the furthest along in testing.

The trial, called REVIVE, included 70 people with polycythemia vera who required frequent phlebotomies to keep their red blood cell numbers low. Adding rusfertide to their ongoing treatment of phlebotomy had a major impact, Dr. Kremyanskaya said.

For most participants who received rusfertide, “[their] need for phlebotomy was significantly reduced or eliminated,” she said, dropping from an average of nine phlebotomies per year before the trial to less than one phlebotomy per year after starting rusfertide.

Results of the trial were published February 22 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“People with polycythemia vera still want to live a normal life … and the problem is that a lot of patients are [constantly] very tired when they receive phlebotomy” over and over again, said Idoroenyi Amanam, M.D., of the City of Hope, who treats people with blood cancers like polycythemia vera but was not involved in the trial.

The findings from this trial are “exciting,” he said. But rusfertide is not yet approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to treat polycythemia vera. And for now, he continued, rusfertide is only available for those participating in a clinical trial.

Treatment options for polycythemia vera

The percentage of blood volume that is composed of red blood cells is known as the hematocrit. For those living with polycythemia vera, the goal of treatment is to maintain a hematocrit below 45%.

To ensure that they stay below that level, people with polycythemia vera regularly visit their doctor to check their hematocrit. If it’s too high, they then undergo therapeutic phlebotomy—a process akin to blood donation—in which a large needle is inserted into a vein to remove blood from the body. The process takes anywhere from 10 to 30 minutes, according to Dr. Kremyanskaya, but the office visit in total can stretch much longer and interfere with people planning their lives.

People with polycythemia vera who are more likely to have problems like blood clots may receive additional treatments to reduce their red blood cell counts. But these treatments also have downsides, including low blood counts and infections. The bottom line, Dr. Kremyanskaya said, is that, beyond phlebotomy, “there are actually very few treatment options.”

Adding rusfertide improves blood counts and symptoms

Rusfertide works by imitating a natural hormone produced by the liver called hepcidin, which controls iron metabolism—that is, how much iron is absorbed from food through the intestines and how much iron is released by iron-storing cells into the bloodstream.

Iron is important for a lot of cellular processes, but especially for red blood cell production, Dr. Kremyanskaya explained.

Treatment with rusfertide essentially tricks the body into behaving as if it has higher hepcidin levels, which causes iron levels to drop in the bloodstream, she continued. And without iron, red blood cell production stops.

Indeed, findings from laboratory and animal model studies suggested that increasing hepcidin activity in the body could potentially limit red blood cell production. Researchers have been testing various therapies that take advantage of this finding, including the hepcidin imitator rusfertide.

The REVIVE study—funded by Protagonist Therapeutics, the manufacturer of rusfertide—is divided into several parts. The findings recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine are from the first two parts of the study.

In the first part of the study, which spanned 7 months, all participants received an injection of rusfertide once a week and continued their ongoing therapy (phlebotomy alone or in combination with other therapy to reduce blood counts) as needed. In the second part of the study, which lasted an additional 3 months, 59 participants were randomly assigned to remain on rusfertide or switch to a placebo. The goal was to assess what would happen when rusfertide was withdrawn.

Before beginning treatment with rusfertide, the mean maximum hematocrit in participants was 50%. That level fell to 44.5% once rusfertide was added to their treatment. As a result, almost none of the participants needed a phlebotomy during the first part of the study.

In addition, participants reported reduced severity of their symptoms, such as fatigue, night sweats, problems concentrating, and itching.

In part two of the trial, 60% of those who stayed on rusfertide but only 17% of those who were switched to placebo had what the trial leaders defined as a response: they maintained a hematocrit below 45% and did not need a phlebotomy.

The most common side effect of rusfertide was a reaction at the injection site, Dr. Kremyanskaya said. For those who had a bad reaction, the injection site could be red, painful, and itchy. But, she noted, those bothersome reactions lessened as the participants remained on the drug.

VERIFYing the benefit

Rusfertide appears to help people with polycythemia vera maintain healthy hematocrit levels without the need for phlebotomy for more than 2 years, according to findings from the third and final part of the REVIVE trial, presented at the American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting in December 2023.

As encouraging as the REVIVE findings are for the reduced need for phlebotomy, the symptom data came from people who were not randomized in the first part of the trial, “and so we have to take it with a grain of salt and see what the randomized data shows,” Dr. Kremyanskaya said.

More definitive findings will come from a larger phase 3 trial, called VERIFY, that is now underway. Unlike the REVIVE study, in which all participants received the drug up front, the VERIFY trial will randomly assign participants to receive rusfertide or placebo from the beginning of the trial.

Watching for additional health problems

One important question to answer is if rusfertide reduces the risk of heart attack and stroke in people with polycythemia vera, Dr. Amanam noted. “The time frame [in the trial] was very short for follow-up, so we don’t have that information yet,” he said.

Another important issue to monitor is second cancers. People with polycythemia vera have an increased risk of both skin cancer and acute myeloid leukemia (AML), although it’s unclear why. Fueling the concern, some existing polycythemia vera treatments—such as the chemotherapy hydroxyurea—are also known to increase skin cancer risk.

As part of the REVIVE trial, all participants received skin examinations by a dermatologist before they began treatment and regularly during the study.

Whether or not rusfertide increases the risk of skin cancer is unknown, “but we need to be vigilant about monitoring,” Dr. Kremyanskaya emphasized.

In addition, Dr. Amanam said it will also be important to see if rusfertide treatment helps control the progression from polycythemia vera to AML.

But he’s hopeful that rusfertide may eventually offer a new option for people with polycythemia vera to recapture part of their lives. “People want to know, ‘Will this help me feel better … and will I be able to live my life in a way that I like to live it?’” he said.

Protagonist Therapeutics said it plans to seek FDA approval for rusfertide for treating polycythemia vera in late 2025.

With several clinical trials testing other hepcidin mimetics already ongoing, there’s a feeling among researchers that managing polycythemia vera may be reaching a turning point, Dr. Kremyanskaya said. “This is a new area of research in polycythemia vera that hopefully will lead to another [treatment option] for patients.”