Study Probes Awareness of Alcohol’s Link to Cancer

, by Anna Hopkins

Numerous changes need to be made to raise public awareness of the fact that drinking alcohol raises the risk of several types of cancer. That’s a key conclusion from a new study conducted by an NCI research team.

The study confirmed that most American adults aren’t aware of the link between alcohol consumption and cancer. It also found that, even among those who are aware, there’s a belief that it varies by the type of alcohol. For example, more participants were aware of the cancer risks from hard liquor and beer than about the risk from wine, with some participants believing wine lowers your cancer risk.

“All types of alcoholic beverages, including wine, increase cancer risk,” said Andrew Seidenberg, Ph.D., who led the study while he was a cancer prevention fellow at NCI. “Unfortunately, there have been very few attempts at educating the public about the alcohol–cancer link. Research is needed to identify what are the best messages and what are the best [ways] to communicate these messages.”

To conduct the study, Dr. Seidenberg, along with William Klein, Ph.D., associate director of NCI’s Behavioral Research Program, and their colleagues looked at responses to an annual health knowledge survey of US adults. The findings were published December 1 in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention.

The study’s findings are important, Dr. Klein said, because they help to “document gaps in awareness that, if addressed, can support system-level efforts to reduce the health impact of alcohol such as higher regulation and changes in social norms.”

Noelle LoConte, M.D., an oncologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who studies alcohol and cancer risk, said that these findings confirm what doctors have long observed.

“One of the most common statements I get when I ask people if they drink is, ‘Well, I only drink beer,’” implying that there is a distinction between beer and liquor in terms of their cancer risks, said Dr. LoConte, who was not involved in the study. “This study gets to the root of where that belief maybe comes from, that hard liquor is worse for you in some way.”

Researchers and health professionals can do more to help break down these misconceptions, Dr. LoConte added. “We need to really make sure that we reinforce the message that all alcohol increases cancer risk,” she said.

How alcohol causes cancer

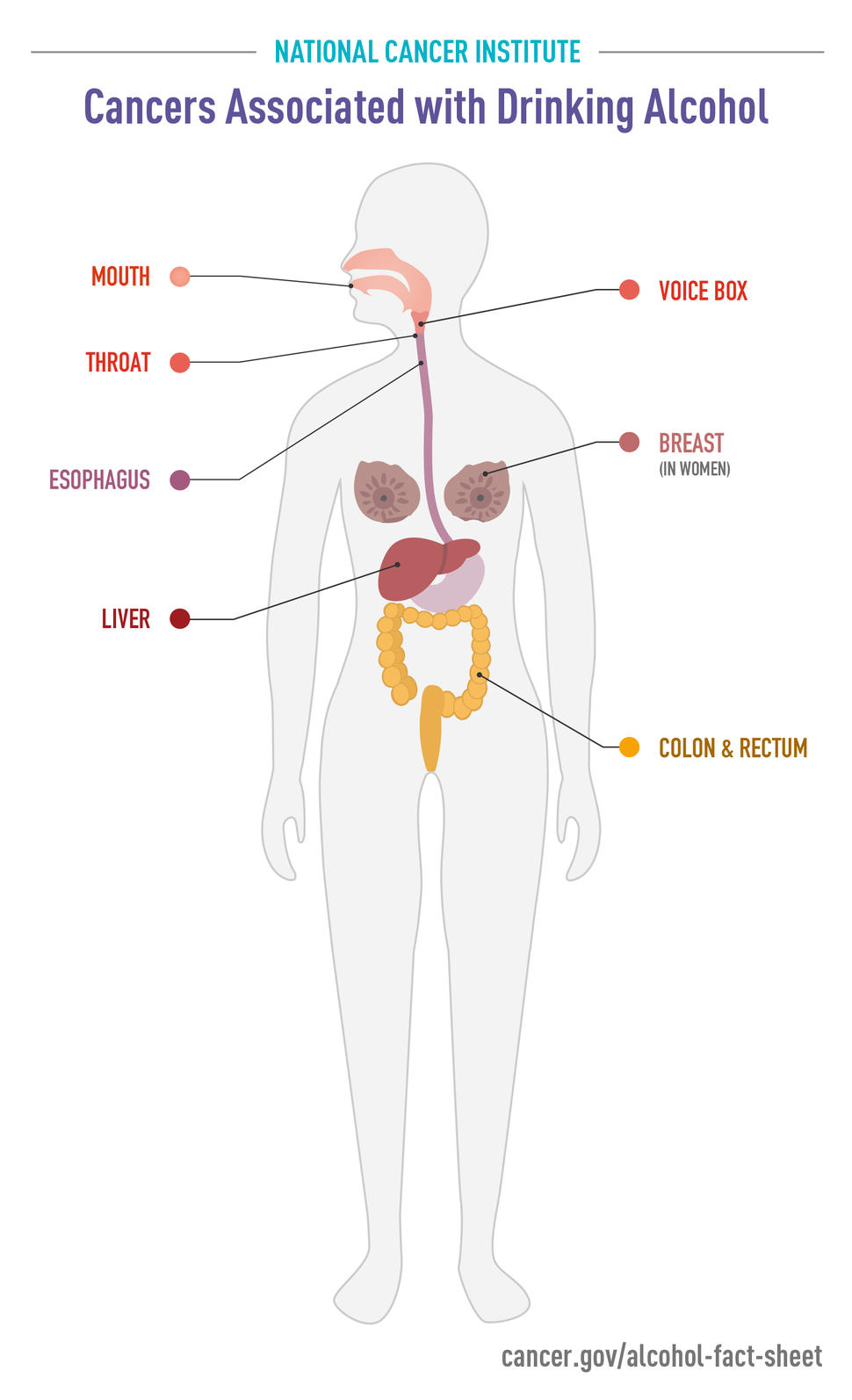

Nearly 4% of cancers diagnosed worldwide in 2020 can be attributed to alcohol consumption, according to the World Health Organization. In the United States alone, about 75,000 cancer cases and 19,000 cancer deaths are estimated to be linked to alcohol each year.

Alcoholic drinks contain ethanol, which is a known carcinogen, and there are several ways in which it may cause cancer. For example, ethanol can increase estrogen in the body, which increases the risk of breast cancer. The breakdown of ethanol in the body can also create high levels of acetaldehyde, which can damage DNA and cause liver, head and neck, and esophageal cancers.

Because cancer risk increases with the amount of ethanol consumed, all alcoholic beverages pose a risk. However, public awareness of this risk is lower than for other carcinogens.

Another recent survey, for example, found that 93% of the US public were aware of the cancer risk associated with tobacco, compared with only 39% for alcohol.

That’s not surprising, Dr. Klein said. There have been decades of public education campaigns about the health risks of tobacco, warning labels on tobacco products, and smokefree laws.

“System-level change, like regulations requiring health warning labels on cigarettes, would have been nearly impossible without greater awareness,” Dr. Klein said. “We just aren’t there yet for alcohol.”

Awareness varies by beverage type

To better understand public knowledge about the cancer risk posed by drinking alcohol and what factors might influence that awareness, Dr. Seidenberg and his colleagues analyzed data from NCI’s 2020 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS), a national mail survey that gathers information on the public’s knowledge about cancer and related health topics.

Participants in the survey are a nationally representative sample of adults aged 18 and older. The nearly 4,000 people who took part in the survey were asked how much does drinking several types of alcohol (wine, beer, and liquor) affect the risk of getting cancer.

Older studies linked moderate alcohol consumption with heart health benefits. However, based on more recent, comprehensive studies, public health experts now generally agree that alcohol—including wine—does not have a so-called “cardioprotective” effect. Nevertheless, the research team also asked participants about the purported heart health benefits of alcohol, to see if it was related to their awareness about alcohol and cancer risk.

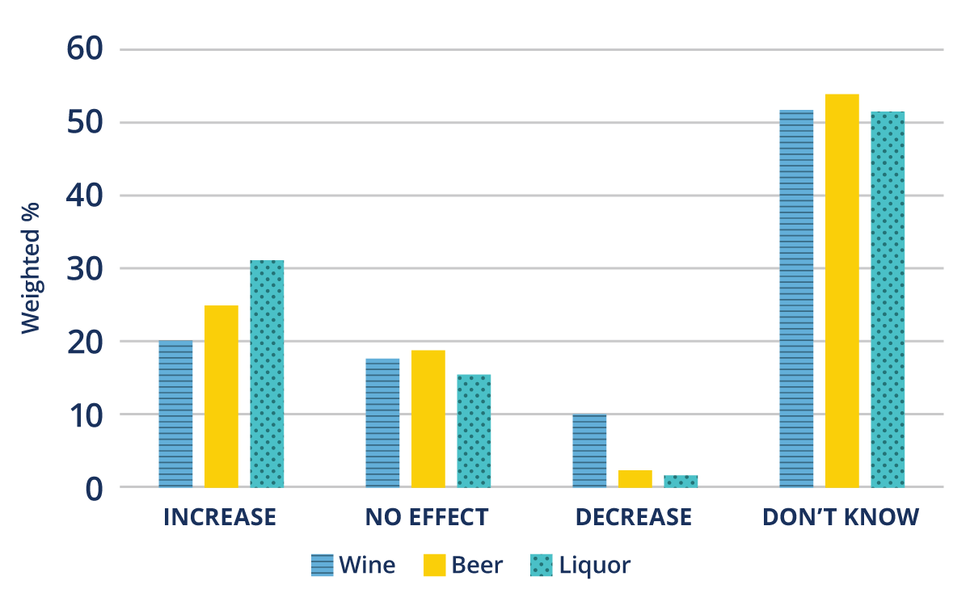

Overall, the researchers found that awareness of the cancer risk associated with drinking alcohol was low. Awareness was highest for liquor, but less than one-third of participants said that liquor increases cancer risk.

Participants were least aware of the cancer risk associated with wine. In fact, about 10% of participants believed that drinking wine actually decreases cancer risk.

The researchers noted similar perceptions about the link between alcohol type and heart disease: Fewer adults believed there is a risk associated with wine than there is from drinking beer and liquor, and more believed that wine lowers the risk of heart disease.

The study also found that people who believed drinking alcohol increased the risk of heart disease were more aware of the alcohol–cancer risk than those who were unsure or believed drinking lowered the effect on heart risk.

People who said they had searched for cancer information were more likely to know about the cancer risks posed by drinking beer and by drinking liquor than those who did not. But awareness of the risk from drinking wine was similar in both those who had and hadn’t sought cancer information.

There was also a difference in awareness based on race: Black adults were less likely to know about the link between wine and cancer than White adults. For all beverage types, those aged 18–39 were more likely to be aware of the cancer risk from alcohol than those aged 40–59 or 60 and older.

Increasing awareness through different approaches

Educating the public about the cancer risk from drinking alcohol, regardless of the beverage type, is especially urgent given the increase in drinking during the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Klein said. One study, for instance, found a 29% increase in drinking in the US in April 2020.

“We are worried that 10 to 20 years down the road, we're going to see a substantial increase in alcohol-related cancers,” Dr. Klein said.

Print and video campaigns are one approach that has been used to raise awareness. Public health campaigns about the cancer risk posed by alcohol in England and Australia have been effective at raising awareness with their target audiences.

Another method that has been shown to be effective is adding information about cancer risks to labels on alcoholic beverages, which currently state that there may be health risks associated with drinking but do not describe what those health risks are (beyond the risk of accidents and of birth defects when alcohol is consumed during pregnancy).

Improving labeling has public support: Another recent study from Drs. Seidenberg, Klein, and their colleagues found 65% of people surveyed would support adding more information about health risks to labels on alcohol containers, and those who were aware of the cancer risk were more likely to support additional labeling.

And health care providers can clearly play an important role in raising awareness, Dr. Klein said.

“It's very clear from our HINTS data that people trust physicians more than any other source of health information, and we've been trying to get out the message that [the doctor’s office is] really a place where this messaging should be more prominent,” said Dr. Klein. “And if it's not one's own [physician], maybe it's the nursing staff, or maybe it's pamphlets in the waiting room.”

The researchers cited the change in public perceptions and tighter regulations for tobacco, which show the importance of public health campaigns and physicians explaining risks to their patients. Dr. Klein noted, "[In] less than half a century, we've seen major changes in the way people think about tobacco."

In an accompanying editorial, Jennifer Hay, Ph.D., of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, and several colleagues agreed that improving awareness “could result in people making more informed decisions about their alcohol consumption,” including encouraging lighter drinkers to continue to limit their consumption and former drinkers to not start drinking again.

It’s imperative to approach this issue in multiple ways, they added, “including those focused on the individual, family, community, and regulation, with the common goal of addressing cancer-related harms associated with alcohol use.”

More research is needed to understand some of the disparities seen in this study, such as with age, Dr. LoConte said.

"We are seeing many more young people who are doing things like Dry January, or doing mocktails out at fancy restaurants, or pushing for those to be on menus,” she noted. Studies looking at why younger people are getting the message about alcohol’s health risks would be very helpful, she continued, because they could guide strategies for reaching other population groups.