For Kids with Medulloblastoma, Trial Suggests Radiation Can Be Tailored

, by Nadia Jaber

Radiation therapy for children and young adults with medulloblastoma—a type of fast-growing brain cancer—may eventually move away from a one-size-fits-all approach. Results of a large clinical trial suggest that some kids can safely get less radiation without limiting their long-term survival, whereas others may need the standard doses.

Although standard treatments cure more than 80% of children with what is known as average-risk medulloblastoma, radiation can cause long-lasting damage to their developing brains. These late effects include difficulties with speech, learning, hearing, and hormone functions.

The trial’s goal was to see if lowering the dose of radiation or delivering radiation to a smaller area of the brain could “maintain a high survival rate without the [negative] consequences of high doses of radiation,” said the study’s leader, Jeff Michalski, M.D., of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Delivering radiation to a smaller area of the brain around the tumor was as effective as radiation to a larger area, according to study results published June 10 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology. But a lower radiation dose didn’t work as well as the standard dose to treat the cancer. However, these patterns were nuanced for patients whose tumors had certain genetic features.

The study ushers in an era of precision medicine in radiotherapy for kids and young adults with medulloblastoma, said Jeffrey Buchsbaum, M.D., Ph.D., of NCI’s Radiation Research Program, who was not involved in the study. Precision medicine is an approach where treatments are tailored to the genetic features of an individual’s cancer.

The results are also driving new clinical trials testing customized treatments for groups of patients with similar genetic features in their cancers, Dr. Buchsbaum said.

Radiation for Medulloblastoma

When a child is diagnosed with medulloblastoma, the cancer is sorted into a risk category (low, average, or high risk) that reflects how aggressive the cancer is and whether it has spread beyond its original location in the brain.

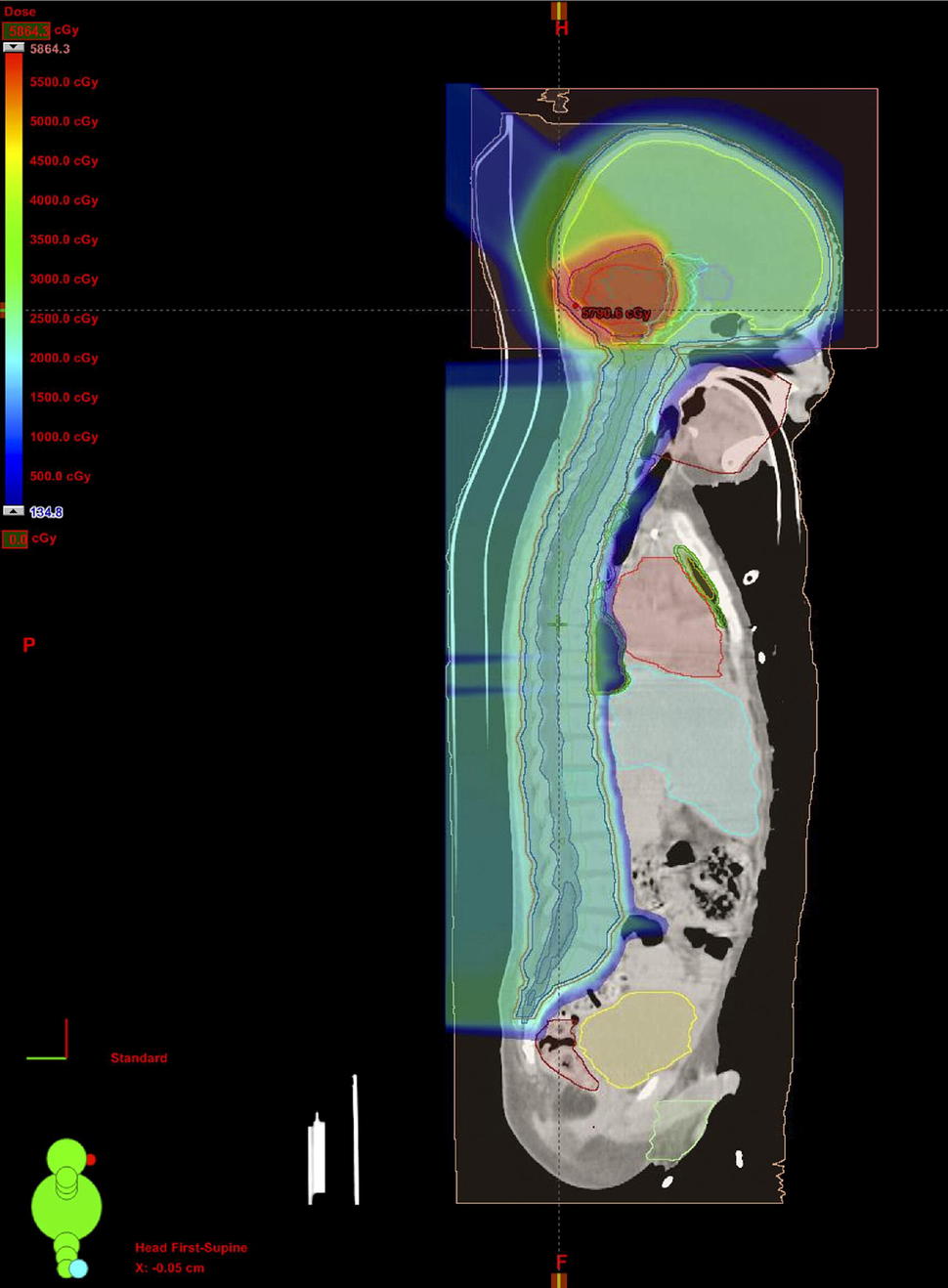

Children with average-risk medulloblastoma typically have surgery to remove as much of the tumor as possible, followed by chemotherapy plus several weeks of radiation. That includes radiation to the whole brain and spine, as well as an extra “boost” to the cerebellum and brain stem, where medulloblastoma tumors start growing.

It’s a very complex and intense treatment, Dr. Buchsbaum noted.

Based on encouraging results from smaller studies, the research team tested a lower dose and a smaller area, or volume, of radiation. They wanted to find out, Dr. Michalski said, “might those two things—reducing the dose and the volume—lead to better cognitive outcomes for the children?”

The study involved 549 children with average-risk medulloblastoma, aged 3 to 21, in six countries. During the study, which followed patients’ outcomes for a median of 9 years, participants took a series of hearing and IQ tests.

Several years after the trial started, basic research studies provided “a better understanding of the biology of medulloblastoma,” leading to a shift in the way the cancer is diagnosed, Dr. Michalski said. Based on this new understanding, doctors now categorize medulloblastoma into one of four subtypes, depending on the genetic changes in patients' tumors.

So, the research team went back and analyzed the genetic features of the participants’ tumors and looked at the study results from the lens of those four subtypes.

The study was funded by NCI and Children’s Oncology Group, two organizations with a long history of conducting clinical trials to reduce the intensity of treatments for children with cancer, Dr. Buchsbaum noted.

A Smaller Volume of Radiation Is Safe

All trial participants received either the standard radiation boost to the base of the skull, or a boost to a smaller area of the brain. The smaller the area, the less healthy tissue that will be hit with radiation, Dr. Buchsbaum explained. That can potentially spare areas of the brain involved in hearing, memory, and hormone regulation, he added.

Among all 464 participants who could be evaluated, 85% were alive after 5 years. And 81% lived for 5 years without having a cancer-related event. A patient was considered to have a cancer-related event if their cancer got worse or came back, if they developed a different kind of cancer (a second primary cancer), or if they died.

A similar percentage of children who received the standard boost and the smaller boost lived 5 years without having a cancer-related event (81% versus 83%). And rates of overall survival were nearly the same for both groups (85%).

In addition, there was some evidence that the smaller boost better preserved patients’ learning abilities—measured by IQ scores—but that needs to be studied further, Dr. Michalski said. However, the smaller boost didn’t reduce rates of hearing loss.

Although the smaller boost effectively treated patients with all four subtypes of medulloblastoma, it seemed to work even better for those with a subtype known as Sonic Hedgehog (SHH).

Nearly 91% of those with the SHH subtype who received the smaller boost lived for 5 years without a cancer-related event, compared with 75% of those who received the standard boost. And none of the patients with the SHH subtype who received the smaller boost developed a second primary cancer, whereas four patients who received the standard boost did.

Low-Dose Radiation Is Less Effective

The researchers also tested a lower radiation dose to the whole brain and spine in the youngest patients, those aged 3 to 7. Damage to the brain is a concern particularly for children younger than 7, whose brains are actively developing in certain key areas, the researchers noted.

Compared with the standard radiation dose, the lower dose caused smaller declines in IQ scores, the researchers found.

But, overall, the lower dose was not as good as the standard dose at keeping the cancer at bay. More children in the low-dose group had a cancer-related event in the following 5 years (29% versus 17%). And fewer children in the low-dose group were still alive after 5 years than those in the standard-dose group (78% versus 86%).

“So, the conclusion is that it’s not safe for all young patients with medulloblastoma to receive a reduced dose of radiation to the brain and spine,” Dr. Michalski said.

However, outcomes varied among patients with specific medulloblastoma subtypes. For example, the lower dose appeared to be just as effective as the standard dose for patients with the WNT subtype (pronounced “wint”).

On the other hand, the lower dose was far worse for those with the group 4 subtype. Among young children with the group 4 subtype, 23% in the low-dose group experienced a cancer-related event in the following 5 years, compared with 3% in the standard-dose group.

Several researchers, including Dr. Buchsbaum, are now conducting follow-up studies of low-dose radiation for children with the WNT subtype of medulloblastoma.

Children’s Oncology Group is also exploring whether drugs that protect against hearing damage may spare children from some of the late effects of the standard medulloblastoma treatments.