Treatments for Oropharyngeal Cancer Are Very Effective, But Are There Ways to Do Less Harm?

, by Carmen Phillips

UPDATE (February 25, 2025): This story has been extensively revised and updated to reflect findings from several clinical trials released since its initial publication.

Although he runs a family business in Florida, Jason Mendelsohn also makes time for something very important to him: raising awareness about oropharyngeal cancer and its strong link with the human papillomavirus (HPV).

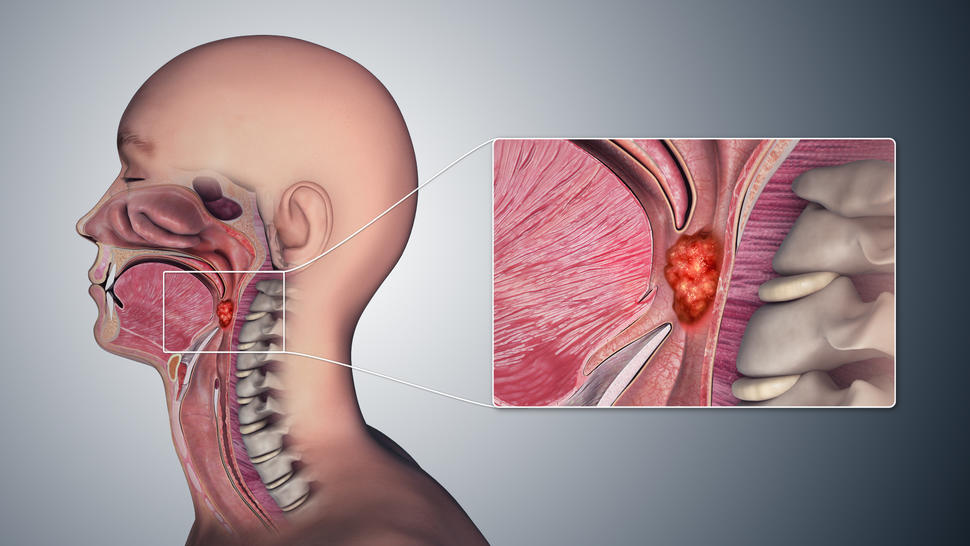

Mr. Mendelsohn was diagnosed with the disease in 2014. The tumor was in one of his tonsils, the most common location for this type of head and neck cancer. His treatment was tough, he explained, including radiation, which caused burning in his throat and severe swallowing problems for a time, and chemotherapy, which led to long bouts of pain and tingling in his toes and fingers, a common side effect called peripheral neuropathy.

While he was undergoing treatment, Mr. Mendelsohn spent more time than he would have liked in bed. “I did get to catch up on six seasons of ‘Lost’ in 2 and a half weeks,” he joked.

In many ways, Mr. Mendelsohn—who is married, has three children, and a decade or so later is in good health—represents the new reality of oropharyngeal cancer. At one time it was found most often in people in their 60s and 70s who were heavy drinkers or smokers. Now, it’s most frequently diagnosed in people between the ages of 40 and 60, predominantly white men, and caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV).

Biologically speaking, oropharyngeal cancers caused by alcohol and smoking and those caused by HPV aren’t the same disease, explained Sue Yom, M.D., Ph.D., a radiation oncologist at the University of California, San Francisco, who specializes in treating head and neck cancers.

People with HPV-positive disease have “such a different survival [rate] than the patients we used to see before,” Dr. Yom said. Their cancers are “so much more responsive to treatment.”

In fact, nearly all HPV-induced oropharyngeal cancers that have not spread beyond the throat area—called localized disease—can be eradicated in most patients by either of two different treatment approaches.

One approach is anchored by a form of robotic surgery, which can be followed by radiation and possibly chemotherapy with the drug cisplatin. But the regimen favored and used by most oncologists is a combination of intensive radiation therapy and high-dose cisplatin. Both regimens are recommended in widely used cancer treatment guidelines.

Although the cancer can come back in a small percentage of patients—regardless of which regimen is used—most are, in effect, cured.

But, as Mr. Mendelsohn’s story illustrates, that cure can come at a physical and mental cost. And, for some people, the harms—including difficulty swallowing, persistent dry mouth, dental problems, and hearing loss—last for years, with a substantial impact on their quality of life.

This tradeoff of a likely cure but with potentially long-lasting side effects has taken on even greater importance over the past two decades, as the number of people diagnosed each year with oropharyngeal cancer has been steadily increasing, explained NCI’s Charalampos Floudas, M.D., who specializes in treating head and neck cancers.

The situation has led many researchers to wonder if it would it be possible to dial down, or deintensify, the treatment of HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer, without jeopardizing the strong likelihood of a long, cancer-free life?

Numerous clinical trials testing less intense treatments, in fact, have been completed, Dr. Floudas said. To date, however, none have shown they are as effective as either of the two recommended regimens. But those setbacks haven’t deterred researchers, with many conducting new trials that are testing many different flavors of deintensification.

A strong case for radiation and high-dose cisplatin

While oncologists wait to see the results of those studies, the case for intensive radiation therapy and high-dose cisplatin has grown even stronger, with updated results from a 400-patient clinical trial called NRG-HN005.

Led by Dr. Yom, the trial compared intensive radiation plus high-dose cisplatin with two deintensification regimens: One that used a lower radiation dose and the other a lower radiation dose plus the immunotherapy drug nivolumab (Opdivo) instead of cisplatin.

As Dr. Yom reported at the 2024 annual meeting of the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO), progression-free survival 2 years after starting treatment—that is, how many people were still alive without their cancer starting to grow again—was 98% in the standard treatment group, “an astounding result,” she said.

The progression-free survival in the other two groups was approximately 90%, which is still quite good overall, Dr. Floudas noted. And although he agreed that the results in the standard treatment group “are very encouraging,” he said it will be important to see the difference in side effects between the three groups once the findings are published in a peer-reviewed journal.

According to Danielle Margalit, M.D., Ph.D., a head and neck cancer specialist at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, the trial was important not because it will change how most patients are treated but because it “really informs [clinical] practice tremendously.”

Intensive radiation with high-dose cisplatin now has the “largest body of scientific evidence and the highest cure rate among all regimens tested so far,” Dr. Margalit said during a presentation at the ASTRO meeting. The results leave no doubt that the regimen should “remain the standard of care.”

Dr. Yom agreed, although she noted that head and neck cancer experts were disappointed that the deintensified regimens didn’t perform better.

“However, the feedback I am getting is that we have learned a lot and need to continue to work on deintensification, taking these lessons forward,” she said.

More data on TORS

Although intensive radiation and high-dose cisplatin is the most commonly used initial treatment for localized HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer, at some hospitals the robotic surgery called TORS is routinely used in its place for selected patients, Dr. Floudas explained. Typically, however, these are large, academic cancer centers.

As is the case for other forms of robotic surgery, surgeons using TORS rely on a tiny camera and sleek metal arms with wrist-like appendages wielding surgical instruments to do their work. But unlike other robotic surgeries, in which the camera and arms are inserted through small incisions, with TORS they enter the body through a natural opening: the mouth.

The robotic system allows surgeons to potentially remove the entire tumor with none of the disfigurement that accompanied open surgery, which, with few exceptions, is no longer used to treat localized oropharyngeal cancer, explained Robert Ferris, M.D., executive director of the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. Dr. Ferris is the lead investigator on the largest trial to date of TORS to treat HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer, called E3311.

All 359 patients in the trial had TORS to remove the primary tumor and any small ones in nearby lymph nodes. From there, participants were placed into one of four groups, based on factors that put them at different levels of risk for their cancer coming back. Those factors included the extent of cancer in their neck lymph nodes at the time of surgery or if there was evidence of cancer in the “margins” around the surgically removed tumor.

Three of the four groups received radiation and chemotherapy after surgery, but not at doses as high as those used in the NRG-HN005 trial. Those in the lowest-risk group received no further treatment after surgery.

Updated results from the trial were presented in June 2024. Across all four groups in the trial, the progression-free survival rates 4.5 years after completing treatment were slightly lower than what was seen with intensive radiation and high-dose cisplatin in the NRG-HN005 trial, ranging from 95% in the second-lowest risk group to 85.5% in the highest-risk group.

The primary treatment–related side effects were throat pain and swallowing issues, but “these appear to resolve in the first few months,” Dr. Ferris noted. Both problems were more severe in those who got higher doses of radiation and chemotherapy, he said.

Even in the absence of randomized trials directly comparing TORS with intensive radiation and high-dose cisplatin, several researchers agreed that, based on the available evidence, robotic surgery alone or followed by lower doses of radiation and chemotherapy is suitable for many patients.

In many cases, Dr. Ferris argued, it comes down to “patient choice and selecting the right patient” for one regimen or the other.

When it comes to choosing surgery, however, he stressed that the surgeon should be experienced using TORS and undergo periodic assessments to get “recredentialed” in performing the procedure (which, at most centers, is usually done every 2 years).

Some deintensification is already happening

Treatment deintensification is already part of the everyday care of some HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer. That’s due, in part, to patients themselves.

“You have patients who say, ‘I’m never taking chemo,’ ‘Don’t ever cut me,’ ‘Radiation, no way I’m having it,’” Dr. Yom explained. Some patients “have that bright line” of what treatments they do and don’t want, she said.

Dr. Floudas agreed, adding that this is why in-depth conversations between patients and doctors about the benefits and risks of treatment are so important.

“When confronted with the full extent of [the likelihood of cure] and potential adverse events, different people are going to have different ‘risk profiles,’” he said. “There are people who want everything done to make their cancer go away, and there are others who, faced with a small but higher risk of recurrence [with a deintensified treatment] will say, ‘I’ll take my chances with that.’”

Ongoing trials in HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer

Dr. Yom advised that any deintensification should be done as part of a clinical trial. Of the ongoing trials involving deintensification, many include different forms of immunotherapy.

For example, a trial being conducted at the NIH Clinical Center, for which Dr. Floudas is an investigator, is testing an experimental HPV treatment vaccine. All patients in the trial will undergo TORS, but first they'll receive the treatment vaccine and a short course of chemotherapy . Those in whom the cancer appears to be eradicated after surgery may not need any further treatment, Dr. Floudas explained.

Other trials are also centered around TORS as the primary, or definitive, treatment. Several, for example, are testing using the levels of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in patients’ blood after surgery to make decisions about whether and how much radiation and/or chemotherapy to deliver.

It will take time to sort it all out, Dr. Yom cautioned. But she’s confident that change isn’t too far off.

“We are very close to having deintensification as a standard option,” she said. But doing so will require developing methods, including using markers like ctDNA and other information about the underlying biology of the tumor, “to select the right patients who can be safely deintensified,” she said. “The community wants to continue to work on this.”

That’s good news for patients, Mr. Mendelsohn said. Because of his involvement in the cancer advocacy community, he explained, he gets lots of questions from people who have just been diagnosed with the disease.

“I never give medical advice,” he said. “But I tell them to talk to their doctor and to really listen to the doctor.” Their oncologist may talk about possible options for less intensive treatment or suggest participating in a clinical trial of deintensified treatment.

Both options, Mr. Mendelsohn said, “should at least be part of the discussion.”