Persistent Poverty Linked to Increased Risk of Dying from Cancer

, by Elia Ben-Ari

It’s been known for some time that poverty is associated with worse cancer outcomes, including a higher risk of dying from cancer. These and other cancer disparities are thought to be caused by many different factors.

A new study by NCI researchers and their colleagues delves more deeply into the links between poverty and cancer deaths in the United States.

The study found that people who live in counties in the United States that experience persistent poverty are more likely to die from cancer than people in other counties. This risk was over and above the heightened risk seen in areas experiencing current—but not persistent—poverty, said study investigator Robert Croyle, Ph.D., director of NCI’s Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences (DCCPS).

These “intriguing findings…provide insight into the social factors that influence health among populations most likely to be adversely impacted—specifically, African Americans and Hispanic Americans,” said Brian Rivers, Ph.D., M.P.H., director of the Cancer Health Equity Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine, who was not involved in the new study.

The findings, which were published September 30 in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, have potentially important implications for policies and other measures aimed at reducing cancer disparities, said cancer epidemiologist Lauren Wallner, Ph.D., M.P.H., of the University of Michigan, who also was not involved in the study.

In addition to trying to modify factors that affect the risk of cancer at an individual level, such as smoking or obesity, “we need to think more broadly about also targeting structural and social factors and inequities” that adversely affect communities experiencing persistent poverty, Dr. Wallner said.

A "Sizeable" Effect of Living in Persistent Poverty

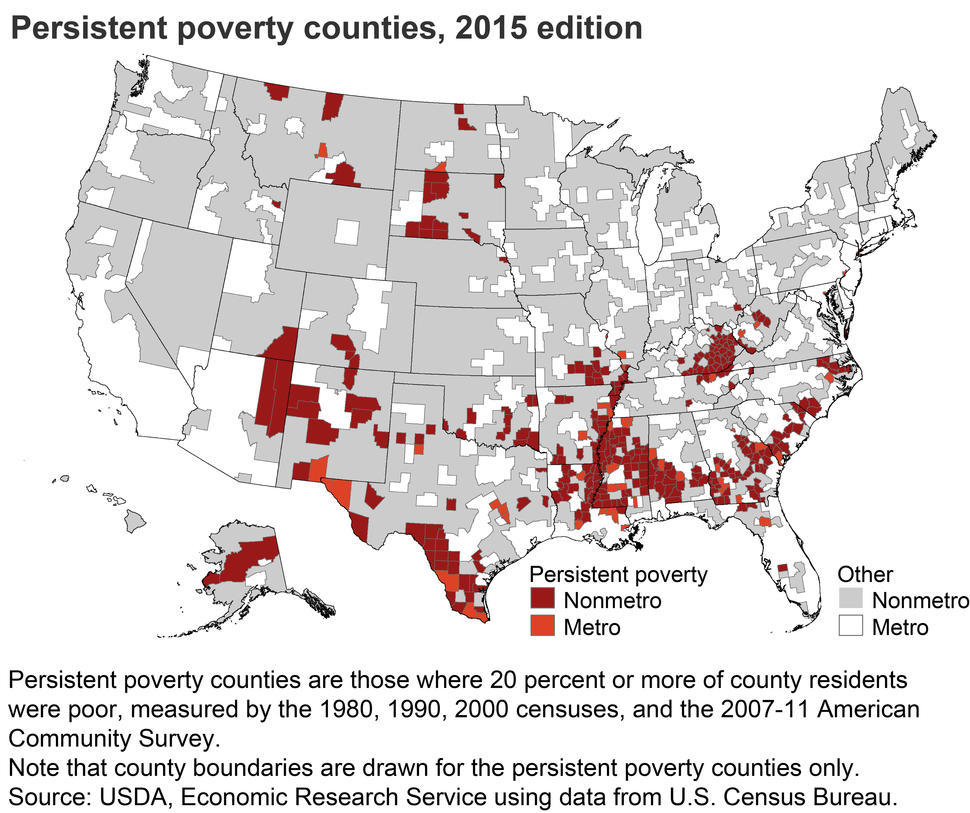

For the study, the researchers gathered cancer mortality data for 2007–2011 for each US county. Persistent poverty counties, according to the US Census, are defined as those with 20% or more of the population living below the federal poverty level since 1980. Current poverty counties were defined as having 20% or more of the population living below the federal poverty level during the study period.

Persistent poverty counties, which accounted for about 12% of all US counties, were unevenly distributed, with many clustered in the southeastern United States. The persistent poverty counties were mainly rural and had higher percentages of Black and Hispanic residents than counties without persistent poverty, the team found.

Previous studies have shown that cancer mortality is higher in rural areas of the United States, which tend to have higher rates of poverty, a lack of access to health care, and other challenges compared with most urban and suburban areas.

In 2007–2011, the annual death rate from all cancer types (overall cancer mortality) was 12% higher in counties with persistent poverty than in counties not experiencing persistent poverty (201.3 versus 179.3 deaths per 100,000 people).

Furthermore, overall cancer mortality was 7.4% higher in persistent poverty counties than in counties experiencing current but not persistent poverty.

The 12% increase in cancer mortality seen with persistent poverty “is a sizeable effect,” Dr. Wallner said. This difference “is approaching the magnitude of racial disparities in cancer mortality” for Black versus White people in the United States, which is about 16%, the study team wrote.

Looking across the most common types of cancer, the team found that persistent poverty was associated with markedly increased risks of dying from several specific cancers, including lung, colorectal, stomach, and liver cancers.

Historical Context Matters When Considering Cancer Disparities

Understanding the interaction among various risk factors associated with poor health outcomes, including living in persistent poverty, being a member of certain racial or ethnic groups, and living in a rural community is important, said study investigator Shobha Srinivasan, Ph.D., senior advisor for health disparities at DCCPS.

“All of these things pile on top of each other, but it’s important to disentangle them” and figure out the exact reasons for the higher cancer mortality rates in persistent poverty counties, Dr. Croyle said. “We’re trying to start systematically doing that … but it’s more complex than is often made out,” he added.

The new study, he continued, demonstrates “the importance of taking into consideration historical context when trying to understand health disparities, and of then developing strategies to reduce those disparities.” In other words, Dr. Croyle said, “you can’t look ahead without looking back.”

Addressing the factors that are fueling the disparities in cancer deaths will require action on many fronts, Dr. Wallner said.

For example, strategies to reduce cancer disparities could include creating outdoor areas where people feel safe exercising and providing access to grocery stores that sell healthy foods. Addressing problems such as racism, crime, and violence, which contribute to health disparities, will also be important, Dr. Rivers said.

To better address the structural and social factors that are driving cancer disparities in poverty-stricken communities, Dr. Rivers said, “we need to better involve leaders at the state and local level." That includes governors, mayors, county commissioners, and city council members, he added.

Developing strategies to address these disparities will require teamwork by experts from diverse fields, including epidemiologists, public policy experts, and economists, Dr. Srinivasan said.

Future Implications

The study did not capture how long people who died of cancer during the study period had lived in the county, Dr. Wallner said. “Living in persistent poverty for a longer time may have even more pronounced effects” on cancer mortality, she said.

In addition, the study did not include information on individual-level factors related to regional differences in cancer mortality, such as smoking or people’s attitudes about seeking medical care if they have cancer.

Nevertheless, Dr. Wallner said, “the study adds quite a bit to what we know about studying disparities above and beyond the individual-level contribution, and to our thinking about how poverty and resources in an area affect those disparities.”

In the future, Dr. Rivers said, scientists studying cancer and other health disparities “must expand how we measure poverty over time” instead of just looking at an individual’s socioeconomic status at one point in time.

Drs. Srinivasan and Croyle agreed that reaching out to, and building trust with, communities experiencing persistent poverty and including them and their residents in future studies also will be important.