Off Target: Investigating the Abscopal Effect as a Treatment for Cancer

, by NCI Staff

The patient had run out of treatment options. Her cancer, a rare form of sarcoma, had metastasized and was no longer responding to therapies.

As a next step, doctors at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis began to treat her largest tumor with proton beam radiation. The goals were to slow the tumor’s growth and keep the 67-year-old patient as comfortable as possible, recalled one of her doctors, Brian Baumann, M.D., a radiation oncologist.

But after one course of proton radiation, the doctors noticed a surprising change in her scans: Not only had the irradiated tumor shrunk, but so had untreated tumors in other parts of her body.

Over time, the tumors would continue to shrink, and eventually they went away.

“Nearly 3 years later, she is alive and doing very well,” said Dr. Baumann. His team reported recently that the patient appeared to have experienced a rare response to treatment known as the abscopal effect.

“The abscopal effect is a fascinating phenomenon,” Dr. Baumann said, noting that it was first observed in experiments with mice in the early 1950s.

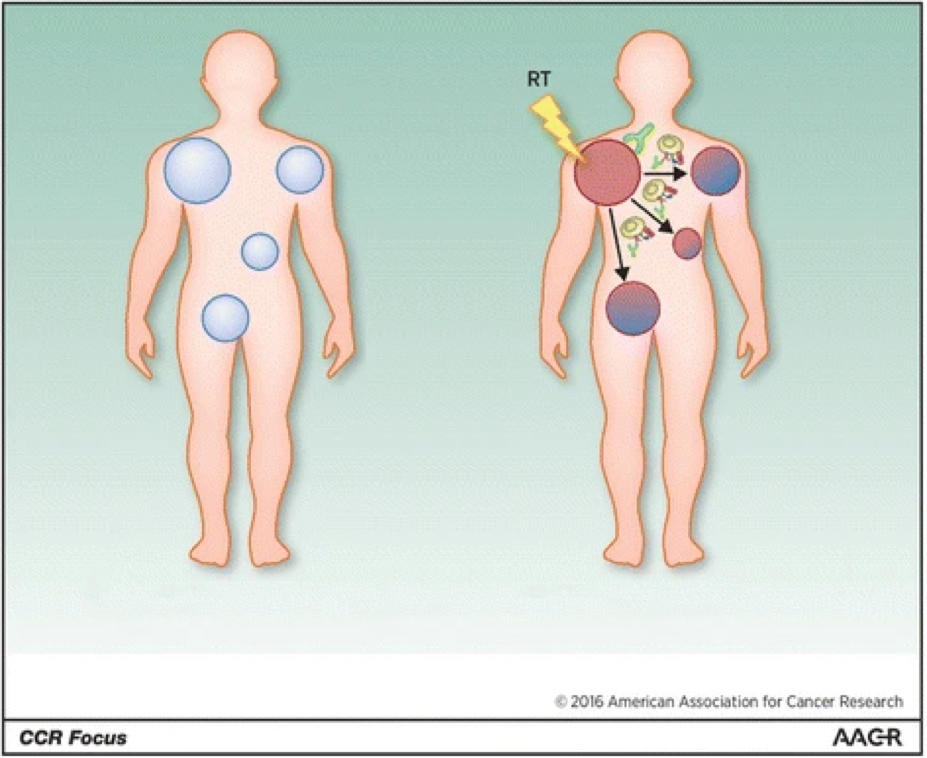

The abscopal effect occurs when radiation treatment—or another type of local therapy—not only shrinks the targeted tumor but also leads to the shrinkage of untreated tumors elsewhere in the body. Although the precise biological mechanisms responsible for the abscopal effect are still being investigated, the immune system is thought to play an important role.

Waking the Immune System

“When you treat a single tumor in a patient who experiences the abscopal effect, you’re waking up the immune system and enabling it to recognize other tumors in the body,” said Billy W. Loo, Jr., M.D., Ph.D., a radiation oncologist at the Stanford Cancer Institute.

In response to radiation, tumor cells may release material that is recognized by the immune system as a threat, potentially leading to an immune response throughout the body, explained Silvia Formenti, M.D., of Weill Cornell Medicine, whose research helped to establish a link between the abscopal effect and the immune system.

“The irradiated tumor can become a kind of vaccine,” added Dr. Formenti. This approach to treating cancer, which can be carried out in various ways, including with radiation therapy, is called in situ vaccination.

In recent years, the availability of new immunotherapy drugs and a greater understanding of how the immune system can work against cancer have contributed to a resurgence of interest in the abscopal effect among researchers, according to Dr. Loo.

The phrase “abscopal effect” was mentioned nearly 120 times in the PubMed database of scientific publications in 2019, up from just 4 mentions a decade ago.

Much of this work has focused on understanding why the abscopal effect occurs. Researchers have also been testing combinations of treatments that may increase the likelihood that the abscopal effect will occur in patients with metastatic cancer.

A Historical Link to Radiation

In the first description of the abscopal effect, in 1953, a researcher named R. H. Mole showed that radiation could shrink a tumor on one side of a mouse and lead to the regression of an untreated tumor on the other side of the animal.

To explain this treatment effect outside the field of radiation, Dr. Mole used the word abscopal, which is derived from the Latin for “away from the target.”

For several decades after Dr. Mole’s report, many radiation oncologists doubted the existence of the abscopal effect, as it was rarely observed. “Because the abscopal effect is unexpected and often dramatic, it became part of the lore of radiation oncology,” said Dr. Loo.

But he and others point to growing evidence that the phenomenon is real and could potentially be made to occur more reliably.

Abscopal responses have been documented in various types of cancer, including melanoma, breast, lung, and liver cancers. In recent years, the effect also has been reported in patients with less common cancers, such as pleural mesothelioma and cancer of the thymus.

Although the vast majority of radiation oncologists have never witnessed the abscopal effect in a patient, those who have say it is remarkable. “As a doctor, you are shocked when you see the abscopal effect in a patient,” said Dr. Formenti. “Once you have seen it, you will remember it forever.”

Overcoming Barriers to the Immune Response

The abscopal effect is uncommon in part because cancer cells have ways to prevent the immune system from finding and killing tumor cells.

“Given how many barriers there are that prevent the immune system from detecting and killing established tumors, radiation alone cannot be expected to elicit the abscopal effect,” said Dr. Formenti. "Some of the established barriers to the recognition and rejection of cancer cells must also be removed."

For the abscopal effect to occur, “you have to overcome the biological mechanisms that are preventing an immune response from eliminating tumors,” said Zachary Morris, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of Wisconsin, who has investigated treatments that could lead to the abscopal effect as part of the Cancer Moonshot℠.

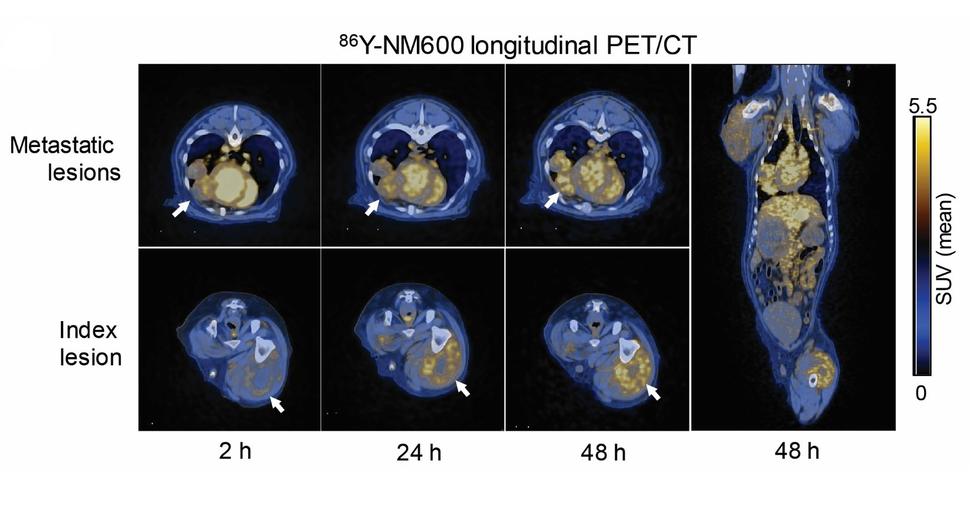

Dr. Morris and his colleagues have been testing in mice an approach designed to restore the ability of the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells once this ability has been lost.

In the approach, known as molecular radiation therapy, low doses of radiation are delivered to all of the tumors in a mouse; at the tumors, the radiation temporarily eradicates immune cells called lymphocytes that are preventing an immune response against cancer cells.

Dr. Morris pointed out that other lymphocytes in the body are unharmed by the radiation and would be available to mount an attack against tumors once the barriers preventing such attacks have been overcome.

“We plan to test the approach in dogs that develop cancer, which are a good model for humans because the cancers have occurred naturally,” he said.

Combining Immunotherapy and Radiation

Another strategy for triggering the abscopal effect is to combine radiation with drugs called immune checkpoint inhibitors, which enhance the immune response to cancer.

There is growing evidence from clinical trials that adding immune checkpoint inhibitors to radiation boosts the chances of an abscopal response in patients, compared with the use of radiation alone.

The two approaches, noted Dr. Morris, may be complementary. Radiation may help the immune system to recognize tumor cells, while immune checkpoint inhibitors help it to respond more strongly.

Although the combination therapy may increase the likelihood of an abscopal response in some patients, the approach still “does not reliably elicit the abscopal effect,” said Dr. Loo, adding that there is “considerable interest in learning how to optimize the strategy.”

Efforts are under way to improve the rates of abscopal responses among patients receiving both therapies, said Mansoor Ahmed, Ph.D., of NCI’s Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, who has led several scientific workshops on the abscopal effect.

“But the lack of data [from laboratory and animal studies] about which doses and methods of delivering radiation are most likely to trigger an abscopal response in combination with immunotherapy has been a big challenge for the field,” he continued.

Discovering Abscopal Responses

Meanwhile, researchers continue to report unexpected abscopal responses associated with the use of various types of treatments that are delivered directly into tumors.

For example, researchers at Columbia University recently observed the abscopal effect during experiments with bacteria that they engineered to deliver a type of immunotherapy drug known as a nanobody into individual mouse tumors. The drug targets a protein called CD47, which promotes the growth of some cancers.

When the bacteria were injected into a mouse tumor, they elicited an immune response that shrank the tumor. Some of the responding immune cells then migrated to other, untreated tumors and slowed their growth as well, the researchers found.

“As we expected, the tumor injected with bacteria disappeared within 10 days, but then we saw a very interesting abscopal effect in untreated tumors,” said coauthor Sreyan Chowdhury, a Ph.D. candidate at Columbia University. “This was a surprise.”

“We think the bacteria are serving a role that is similar to that of radiation in terms of stimulating an abscopal response,” he added, noting that once the bacteria were injected into a tumor, they did not themselves spread to other tumors.

The approach could be a way to stimulate the immune system to find and attack tumors that are too small to be detected using imaging tools, added coauthor Tal Danino, Ph.D., a biomedical engineer at Columbia.

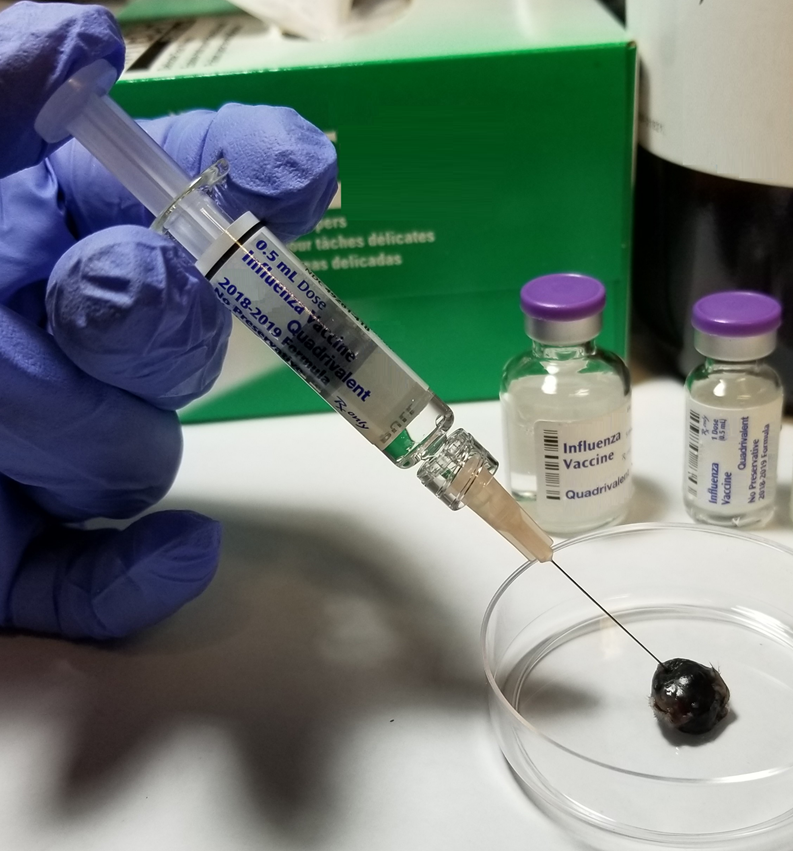

Flu vaccines may be another treatment that could elicit the abscopal effect when injected into tumors, according to findings from a recent study of mice that had melanoma tumors on opposite sides of their bodies.

Injecting a flu vaccine into one tumor not only reduced the growth of that tumor but also slowed the growth of the untreated tumor on the opposite side of the animal, researchers found.

“We saw the tumor growth slowing on both sides of the mouse almost simultaneously,” said lead investigator Andrew Zloza, M.D., Ph.D., of Rush University Medical Center, whose laboratory has investigated how infectious agents, such as HIV, alter the body’s response to cancer.

His team also injected flu vaccine into the tumors of mice with a form of breast cancer that spreads to the lungs, and the results were similar to those of the mice with melanoma.

In all of the mice, the flu vaccine drew certain immune cells that can recognize and attack cancer cells to the injected tumor. This changed the local tumor environment, setting the stage for the migration of some of these immune cells to other tumors, the researchers found.

“These immune cells can travel if there is a form of danger somewhere else,” said Dr. Zloza. “So, they can find the other tumors in the body.” More research, he noted, is needed to determine which types of immune cells were most important in the abscopal responses in the mice.

To try to improve their results, the researchers treated mice with an immune checkpoint inhibitor as well as the flu vaccine—and the strategy worked. The combination treatment yielded better responses in the mice than had occurred with the flu vaccine alone.

Flu vaccines approved by the Food and Drug Administration, which are inexpensive, readily available, and safe, could be tested in clinical trials as a potential treatment for cancer, noted Dr. Zloza, who is planning some of these trials.

“It’s time for a clinical trial,” he continued. “We need to see whether the flu vaccine can be repurposed as a cancer drug.”

Exploring Proton Radiation

The patient with sarcoma who was treated at Washington University School of Medicine and experienced the abscopal effect was among the first people to have such a response following treatment with proton radiation.

Dr. Baumann pointed out that, when it comes to triggering abscopal responses, proton radiation may have certain advantages over more conventional types of radiation, which use high-energy radiation from x-rays, gamma rays, or neutrons.

A difference between these types of radiation is that gamma and x-ray beams do not stop as they pass through the body, whereas the depth of proton therapy beams can be controlled, potentially limiting the amount of radiation that inadvertently reaches healthy tissues.

“With protons, you expose less of the body to radiation, which means you expose less of the blood and the circulating immune cells in the blood, which can kill tumor cells, to radiation,” Dr. Baumann explained.

“Immune cells are very sensitive to radiation,” he continued. “Higher exposure of immune cells to radiation can cause the immune cells to die, which may dampen the abscopal effect.”

More research, he added, is needed to explore the potential benefits of using proton radiation to treat other patients with the same type of sarcoma.

More Research and “New Rules”

Dr. Formenti noted that research is also needed to determine more effective and reproducible ways to use radiation to stimulate abscopal responses in patients with metastatic cancer.

Although many clinical trials are testing immunotherapy and radiation in patients with cancer, no large clinical trial has yet provided evidence to establish how the radiation should be delivered—and in which doses—to try to elicit the abscopal effect.

"We may have to change the way we deliver radiation to get the best results,” she said. “It may not be as simple as administering radiation the way it has generally been done.

“When it comes to the abscopal responses,” Dr. Formenti continued, “there may be some new rules we need to follow—and we are still figuring out what those rules are.”