Expanding Cancer Clinical Trial Access for Patients with HIV

, by Elad Sharon, M.D., M.P.H. and Thomas Uldrick, M.D.

UPDATE: On June 2, 2019, final results from the CITN-12 trial were presented at the American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting. The presentation, which included data from 30 trial participants, showed that participants’ HIV levels remained suppressed throughout the study, and most side effects were considered low-grade. Side effects attributed to pembrolizumab treatment included hypothyroidism, rash, and arthritis. One participant with Kaposi sarcoma (KS) who entered the trial with elevated levels of KS-associated herpesvirus had a substantial increase in levels of the virus and later died.

One trial participant with lung cancer had a complete disappearance of his disease (complete response) and continued to be cancer free 2 years after finishing treatment. In addition, two participants with non-Hodgkin lymphoma had partial reductions in their disease (partial response) and eight participants with KS saw their disease stabilize for at least 24 weeks.

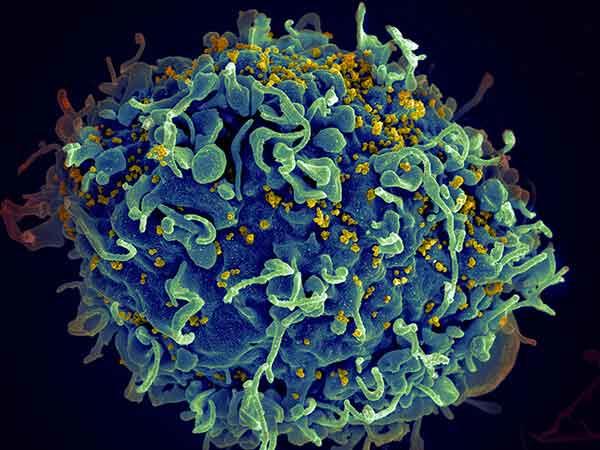

Infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was once a highly fatal disease. But decades of biomedical research, culminating in highly effective therapies, have transformed it into a manageable and chronic condition. With the availability of current antiretroviral therapies, most people with HIV can expect to live as long as people without the infection.

However, HIV-positive people are still at higher risk for some types of cancer than those who are HIV negative. And because people with HIV are living longer, more of them are developing cancers that are common in older age groups. In fact, in the United States, cancer is now the leading cause of death among people with HIV.

Unfortunately, people with HIV are typically excluded from participating in clinical trials of new cancer treatments because of concerns that the treatments may be unsafe for them. As a result, data on the use of these drugs in people with cancer who are HIV positive is not available from clinical trials.

Dr. Sharon is a senior investigator in NCI’s Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program. Dr. Uldrick, previously with NCI’s HIV and AIDS Malignancy Branch, is now an investigator at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. Both are a part of the Cancer Immunotherapy Trials Network-12 trial.

Because there is little evidence that the new treatments are safe or effective for people who are HIV positive, doctors are less likely to prescribe these newly approved cancer treatments to their patients with HIV (who would otherwise be eligible to receive them). This cycle of exclusions may significantly delay people with HIV from accessing potentially life-saving cancer therapies.

The issue is especially relevant in the case of immunotherapy, a new and promising class of cancer therapy. Certain immunotherapies are approved to treat cancers that HIV-positive individuals are at increased risk of developing, but doctors do not currently know if these treatments are safe or effective for people with HIV.

For many years, NCI has recommended that people with HIV should not be arbitrarily excluded from cancer clinical trials and has enrolled people with HIV in immunotherapy trials. Early results from one such NCI-sponsored trial appear to validate the inclusion of appropriately selected HIV-positive people in immunotherapy clinical trials.

The trial, conducted by NCI’s HIV and AIDS Malignancy Branch and the Cancer Immunotherapy Trials Network (CITN), is testing the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab (Keytruda®) specifically in people with advanced cancer who are HIV positive.

Interim results from the first 17 participants, presented by Dr. Uldrick on November 10 at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC), show that pembrolizumab had an acceptable safety profile for HIV-positive patients.

Exclusion of HIV-positive People from Immunotherapy Trials

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are immunotherapy drugs that help the immune system kill cancer cells. Several of these drugs are approved to treat a growing number of cancer types, and they have provided lasting responses—years long, in some cases—for some people with these cancers.

But many people with cancer who are HIV positive are not offered these therapies because they have routinely been excluded from the vast majority of immunotherapy clinical trials.

There are concerns that HIV infection could impact the safety and efficacy of immunotherapies because HIV infection weakens the immune system (especially if the infection is poorly controlled). There are additional concerns that antiretroviral therapies might interact with cancer drugs in a negative way, causing more side effects in HIV-positive individuals than in HIV-negative individuals. However, strong scientific evidence to support these concerns is lacking.

Here’s the catch-22: If HIV-positive patients are barred from participating in immunotherapy trials, we will never be able to determine if their exclusion is warranted.

NCI’s Role in Expanding Trial Access

The NCI-sponsored trial, called CITN-12, is evaluating pembrolizumab in people with HIV who have relapsed or refractory cancer and who are also taking antiretroviral therapy.

The preliminary results presented at the SITC meeting showed no negative interactions between pembrolizumab and antiretroviral therapy. Most of the treatment-related side effects participants developed were not considered to be severe (for example, fatigue and nausea). In addition, the side effects observed were similar to those observed in HIV-negative patients treated with pembrolizumab.

In the trial, the functionality of each participant’s immune system was measured by the number of immune cells, called helper T cells, in the patient’s blood before treatment with pembrolizumab. Based on this analysis, participants were separated into three levels of immune function: moderate dysfunction, mild dysfunction, or relatively normal.

There were no differences in the quantity and type of severe side effects based on patients’ level of immune function. These findings suggest that pembrolizumab treatment does not appear to lead to more side effects in patients with a weak immune system than in patients with normal immune system function.

Trial enrollment is ongoing, and the physicians leading the trial will continue to carefully evaluate the safety of pembrolizumab treatment. They will also evaluate the efficacy of the treatment, as well as its effect on HIV infection.

Although our results are very preliminary, they are encouraging. This trial, along with many other NCI-sponsored studies, has demonstrated that people with HIV can safely participate in clinical trials. Importantly, these trials have helped to define appropriate trial eligibility criteria for people with HIV that may inform the design of future clinical trials.

Broader clinical trial access will be a major advance for people with HIV and cancer. Including people with HIV on more clinical trials can lead to tremendous changes in how cancer is treated in these patients, with the potential to save many lives.