CAR T Cells: Expanding into Multiple Myeloma

, by NCI Staff

A box with updated information was added to this post on December 12 to reflect the presentation of new data.

Results from two early-phase clinical trials suggest that a form of immunotherapy that uses genetically engineered immune cells may be highly effective in patients with advanced multiple myeloma.

Both trials used CAR T cells that were engineered to target a protein on myeloma cells called B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA). Although most patients in the trials had good responses to the treatment, including many who experienced complete remissions, the length of time that most patients have been followed after receiving the treatment is still limited, researchers from both trials cautioned.

Preliminary findings from the trials were presented this week at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) annual meeting in Chicago. One trial was conducted in China and the other in the United States.

Serious side effects, including immune-related effects seen in other CAR T-cell trials, have been limited in the patients treated to date, reported the investigators leading the trials.

Although it’s still too early to determine whether these BCMA-targeted CAR T cells will eventually become standard treatments for multiple myeloma, some researchers were encouraged by the early results.

“The science behind [CAR T cells] is getting to be quite revolutionary,” said Michael Sabel, M.D., of the University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center, during a press briefing on the results of the Chinese trial. But more research is needed, Dr. Sabel continued, to validate these early findings and “to see if we can make this type of therapy accessible to more patients.”

An Emerging Form of Immunotherapy

A form of immunotherapy known as checkpoint inhibition is rapidly becoming an established part of everyday cancer care. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved checkpoint inhibitors, which are biologic drugs known as humanized monoclonal antibodies, for more types of cancer, including melanoma, lung cancer, lymphoma, and bladder cancer.

And in May, the agency approved the checkpoint inhibitor pembrolizumab (Keytruda®) for use in adults or children with advanced cancer—regardless of their type of cancer—whose tumors have one of two types of genetic alterations.

CAR T cells, on the other hand, use a patient's own immune cells to treat their disease and are still largely in the clinical development phase.

In this form of therapy, immune cells are collected from a patient’s blood; engineered in the laboratory to produce special receptors called chimeric-antigen receptors, or CARs, that attach to a specific target on cancer cells (an antigen); grown in the lab until they number in the billions; and then reinfused back into the patient.

Two companies have recently filed approval applications with FDA for their CAR T-cell therapies, one for lymphoma and the other for leukemia.

The CAR T-cell products under development differ from one another in several ways, including the antigen on tumor cells that they are engineered to target. Both of the CAR T-cell products that have been submitted for FDA approval, including one initially developed at NCI, target the CD19 antigen.

CAR T cells that target BCMA are relatively new. BCMA-targeted CAR T cells were first tested in 2014 at NCI, and several other ongoing trials, in addition to the two reported at ASCO, are testing them.

In blood cells, the expression of BCMA is limited primarily to normal and cancerous plasma cells, explained James Kochenderfer, M.D., of the Experimental Transplantation and Immunology Branch in NCI’s Center for Cancer Research. BCMA is expressed in most patients with multiple myeloma, he added, and it’s not expressed on any nonblood cells.

“The most important factor in deciding what antigen to target with a CAR is to pick one that is not expressed on essential normal tissues,” said Dr. Kochenderfer, senior author of the US-conducted trial. Dr. Kochenderfer’s lab developed the first BCMA-targeted CAR T cells and, in 2014, he and his colleagues at NCI conducted the first human trial to test BCMA-targeted CAR T cells.

Many Remissions

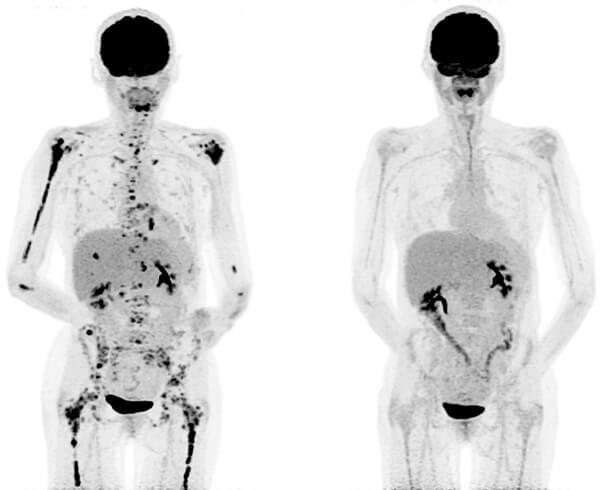

In the Chinese trial, which is being funded by Nanjing Legend Biotech, 33 of the 35 patients in the study went into complete remission within 2 months of receiving the BCMA-targeted CAR T cells, reported trial investigator Wanhong Zhao, M.D., Ph.D., of Xi’an Jiaotong University. The remaining two patients also had tumor responses, Dr. Zhao said.

Of the 19 patients who have been followed for at least 4 months, 14 have had what is called a stringent complete response (sCR)—that is, no evidence of the disease in their bone marrow or other markers of the disease in other tests—to the treatment, which the company is calling LCAR-B38M CAR T cells. Of the 14 patients with an sCR, the 5 who have been followed for at least a year still have no signs of cancer, Dr. Zhao said.

Jesus G. Berdeja, M.D., of the Sarah Cannon Research Institute in Tennessee, presented updated findings from the other trial of BCMA-targeted CAR T cells, which is being funded by bluebird bio, Inc. To date, 21 patients have been treated on the trial. Dr. Berdeja reported on data from 18 of these patients. (The remaining three have not been on the trial long enough to be evaluated.)

Of the 18 patients in the trial treated with the higher dose of CAR T cells, 17 (94%) had a tumor response. Ten of those responses (56%) were complete responses, Dr. Kochenderfer reported, and 9 of those 10 patients have no evidence of residual disease by the most sensitive tests available.

In several patients, responses to the one-time treatment have been maintained for more than a year.

Five patients experienced neurologic effects from the treatment, and 15 had at least mild CRS. In all cases the problems resolved quickly, Dr. Kochenderfer reported.

Celgene and bluebird, which are jointly developing bb2121, announced that they have begun enrolling patients in a phase 2 trial called KarMMa to continue to study the treatment in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma.

As is often done in phase I trials, different doses of the CAR T-cell product—which the company is calling bb2121—were tested, with the intention of gradually increasing the dose if no serious side effects were seen and establishing the best dose to test in larger trials.

Only one of the first three patients treated at the lowest dose of CAR T cells responded. Beyond this first-level dose, however, the overall response rate was 100%, with 27% of patients experiencing an sCR and the remainder having what is known as a very good partial response (based on widely used and accepted criteria).

“These patients were heavily pretreated,” Dr. Berdeja said. The median number of prior treatments was seven, he noted; all of the patients in the trial had at least one stem cell transplant, and several have had multiple transplants.

The strong responses in patients who had been so heavily pretreated are not the only encouraging findings from the trial, Dr. Berdeja said.

“What’s so striking is that the tumor cells are killed so quickly that all the other parameters [of treatment response] lag behind,” he said.

Manageable Side Effects

All patients undergoing CAR T-cell therapy are closely monitored for a known side effect called cytokine release syndrome (CRS), a massive storm of immune signaling cells called cytokines that can be fatal.

Minor cases of CRS were common in both trials, the researchers reported, but were generally short lived and managed with standard therapies.

Several patients in both trials experienced severe CRS following treatment, which was treated successfully with the drug tocilizumab (Actemra®).

No patients in either trial experienced neurotoxicity, another serious side effect that has been seen in several other trials of CAR T cells and, in one case, led a company to discontinue development of its lead CAR T cell treatment.

Differences in the Therapies, Trials

Unlike most other trials of CAR T cells, including the bluebird trial, patients in the Chinese trial received three smaller doses of the cells rather than a single large dose. Patients received a relatively small dose on their first day of therapy, and then two progressively larger doses on days 2 and 6.

This was done largely for safety reasons, explained Frank Fan, Ph.D., the chief scientific officer for Nanjing Legend. In some cases, if patients were experiencing CRS or any other potentially serious side effect after the second dose, the third dose was not given, Dr. Fan said.

The receptor on the LCAR-B38M CAR T cells is also different from those on most other CAR T cells in development, he continued, in that it can attach to two different parts of the same antigen. This difference, he believes, may improve its ability to bind to and kill tumor cells.

Interpreting the significance of the Chinese trial results is difficult because of some important missing details, said Marcela Maus, M.D., Ph.D., director of Cellular Immunotherapy at the Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center.

During an abstract discussion session at the meeting where the trial results were presented, Dr. Maus said more information is still needed on the extent and types of prior therapies received by patients, the criteria used to determine the treatment responses, and the composition of the T cells used in the therapy administered to patients.

In the bluebird trial, not only had all of the patients been heavily pretreated, Dr. Berdeja said, but nearly 30% of patients were resistant to all of the major drug classes used to treat multiple myeloma.

Next Steps

The researchers leading the Nanjing Legend trial are continuing to enroll patients in their trial and are filing the regulatory paperwork with FDA to launch a similar trial in the United States early next year, Dr. Fan said.

The bluebird trial will now proceed to what is known as the dose-expansion stage, Dr. Berdeja explained, using the dose established as most safe and effective in the trial’s initial dose-escalation stage.