Prevention of Ovarian Cancer

Women who carry harmful or potentially harmful mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes are at increased risk of developing ovarian cancer. Surgery to remove the ovaries and fallopian tubes in these women is the recommended treatment method and can reduce their lifetime risk of getting ovarian cancer by 95%. However, having this surgery causes immediate menopause. This may cause health problems if it is much earlier than naturally occurring menopause.

Research has shown that the most common type of ovarian cancer begins in the fallopian tubes, not in the ovaries. This discovery has led doctors to reconsider ways of preventing ovarian cancer.

- Removing fallopian tubes only. An ongoing NCI-supported clinical trial is testing whether removing the fallopian tubes but delaying removal of the ovaries will be as safe and effective to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer in women with BRCA1 mutations as removing both the ovaries and fallopian tubes at the same time. This would allow women to maintain premenopausal levels of hormones produced by the ovaries and delay many of the complications associated with menopause.

- Removal of fallopian tubes in people seeking to prevent pregnancy. The discovery that epithelial ovarian cancers most often start in the fallopian tubes has also led to changes in the way some gynecologists approach surgery to prevent pregnancy. Women seeking tubal ligation to prevent pregnancy (often called having your tubes tied) may be offered the option of having their tubes removed instead. Doing so might reduce the possibility of ovarian cancer in the future.

- Removal of fallopian tubes in people undergoing a hysterectomy. Similarly, some gynecologists recommend that their patients who are undergoing a hysterectomy also have their fallopian tubes removed.

- Testing relatives for gene mutations. NCI is funding efforts to test the relatives of women who have been diagnosed with ovarian cancer in the past. Researchers are locating women diagnosed with ovarian cancer with the hope to test them and/or their family members for ovarian cancer-related gene mutations. As a result, family members who learn they carry a mutation can take steps to reduce their risk. The overall goal is not only to prevent ovarian cancer, but also to find the best ways to communicate sensitive genetic information to ovarian cancer patients and their family members.

Ovarian Cancer Treatment

Surgery and chemotherapy are the main treatments for ovarian cancer. The location and type of cells where the cancer begins, and whether the cancer is high-grade or low-grade, influences how the cancer is treated. Surgery can cure most people with early-stage ovarian cancer that has not spread beyond the ovaries. For advanced ovarian cancer, the goal of surgery is to remove as much of the cancer as possible, called surgical debulking.

Platinum-based chemotherapy drugs, such as cisplatin or carboplatin, given in combination with other drugs, such as the targeted therapy bevacizumab (Avastin), are usually effective in treating epithelial ovarian cancer at any stage. However, in most people with advanced ovarian cancer, the cancer comes back. Treating the cancer again with platinum drugs may work, but eventually the tumors become resistant to these drugs.

Targeted Therapy

Targeted therapy uses drugs or other agents to attack specific types of cancer cells. PARP inhibitors are a type of targeted therapy that can stop a cancer cell from repairing its damaged DNA, causing the cell to die. Cancers in people who have certain mutations in the BRCA genes are considered particularly susceptible to PARP inhibitors. That’s because BRCA genes are involved in the repair of some types of DNA damage, so cancers with alterations in these genes already have defects in DNA repair.

The use of PARP inhibitors has transformed treatment for people with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer who have harmful mutations in a BRCA gene. Since the 2014 approval of olaparib (Lynparza), the first PARP inhibitor to be approved, the number of PARP inhibitors has grown and their uses for people with ovarian cancer have expanded. Now researchers are studying the benefits of combining PARP inhibitors with other drugs.

Clinical trials have shown that using PARP inhibitors as long-term therapy in women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer delayed progression of the cancer.

A different targeted therapy, mirvetuximab soravtansine (Elahere), is now available to treat women with ovarian cancer that is no longer responding to platinum drugs. FDA recently approved the drug to treat people with platinum-resistant ovarian tumors that produce an excess of a protein called FR-α. Results from a large clinical trial showed that people with this type of ovarian cancer treated with mirvetuximab lived longer overall than people treated with standard chemotherapy.

Treatment after Cancer Progression

Typically, chemotherapy and targeted therapies are stopped once ovarian cancer begins to come back. Clinical trials have shown that where there was more than a 6 month delay between stopping treatment and cancer being found again, resuming the drug bevacizumab (Avastin) in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy for patients previously treated with bevacizumab slowed the growth of platinum-sensitive disease. And in women who no longer benefited from platinum-based chemotherapy, non–platinum-based chemotherapy combined with bevacizumab kept the cancer in check longer than chemotherapy alone.

Targeted therapies may also be helpful for people with low-grade ovarian cancer. A trial of the drug trametinib in women with low-grade serous ovarian cancer that had come back showed that it delayed the cancer’s growth compared with treating the cancer with chemotherapy again.

Secondary Surgery

For women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer that has come back after being in remission, clinical trials have studied the use of secondary surgery or surgery to remove more tumor after the initial surgery with varying results.

- An NCI-funded phase 3 clinical trial, in patients whose doctor felt that a second surgery could be helpful for treating the cancer, found that secondary surgery followed by chemotherapy did not increase overall survival compared with chemotherapy alone. Of the studies listed, this one reflected the most likely scenario in real-world practice.

- A trial done in China studied a group of patients more likely to benefit from the intervention. The trial tested secondary surgery followed by chemotherapy and did show improvements in how long women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer lived without their cancer growing.

- In a third trial, conducted in Europe, researchers identified people with recurrent ovarian cancer who were most likely to benefit from surgery. They found that women who had secondary surgery followed by chemotherapy lived an average of nearly 8 months longer than women who only received chemotherapy.

In the Chinese and European trials, and in an analysis of 64 clinical trials and other studies, the benefits of secondary surgery were observed only in women who had all of their visible cancer removed.

NCI-Supported Research Programs

Many NCI-funded researchers at the National Institutes of Health campus, and across the United States and the world, are seeking ways to address ovarian cancer more effectively. Some research is basic, exploring questions as diverse as the biological underpinnings of ovarian cancer and the social factors that affect cancer risk. And some is more clinical, seeking to translate this basic information into improving patient outcomes.

The Women’s Malignancies Branch in NCI’s Center for Cancer Research conducts basic and clinical research in breast and gynecologic cancers, including early-phase clinical trials at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland.

The Ovarian Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPOREs) promote collaborative translational cancer research. This group works to improve prevention and treatment approaches, along with molecular diagnostics, in the clinical setting to help people with ovarian cancer.

The Ovarian Cancer Cohort Consortium, part of the NCI Cohort Consortium, is an international consortium of more than 20 cohort studies that follow people with ovarian cancer to improve understanding of ovarian cancer risk, early detection, tumor differences, and prognosis.

NCI’s clinical trials programs, the National Clinical Trials Network, Experimental Therapeutics Clinical Trials Network, and NCI Community Oncology Research Program, all conduct or support clinical studies of ovarian cancer.

Clinical Trials for Ovarian Cancer

NCI funds and oversees both early- and late-phase clinical trials to develop new treatments and improve patient care. Trials are available for the treatment of ovarian cancer.

Ovarian Cancer Research Results

The following are some of our latest news articles on ovarian cancer research:

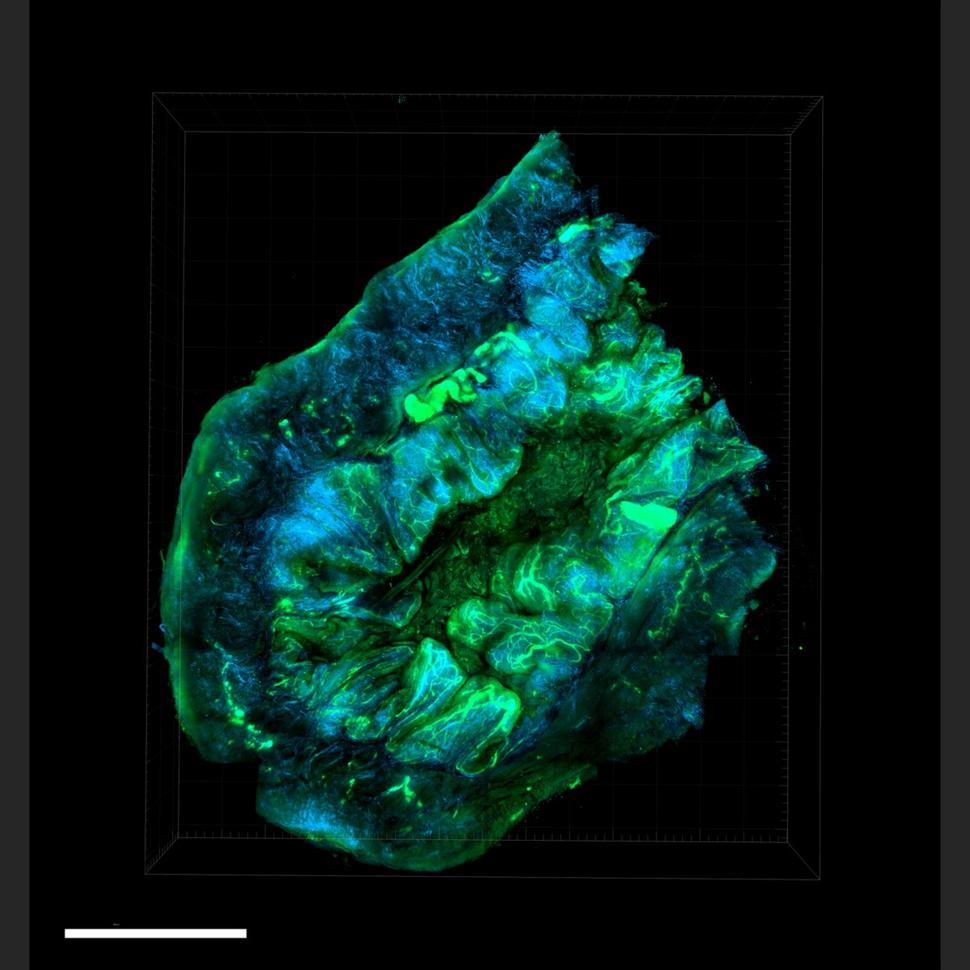

- What’s at the Root of Ovarian Cancer? New Study May Have Found Part of the Answer

- Approval of Elahere Expands Treatment Options for Some Advanced Ovarian Cancers

- Implanted “Drug Factories” Deliver Cancer Treatment Directly to Tumors

- Trametinib Is a New Treatment Option for Rare Form of Ovarian Cancer

- When Ovarian Cancer Returns, Surgery May Be a Good Choice for Selected Patients

- How Does Ovarian Cancer Form? A New Study Points to MicroRNA

View the full list of Ovarian Cancer Research Results and Study Updates.