Childhood Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors (PDQ®)–Patient Version

What is childhood gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor?

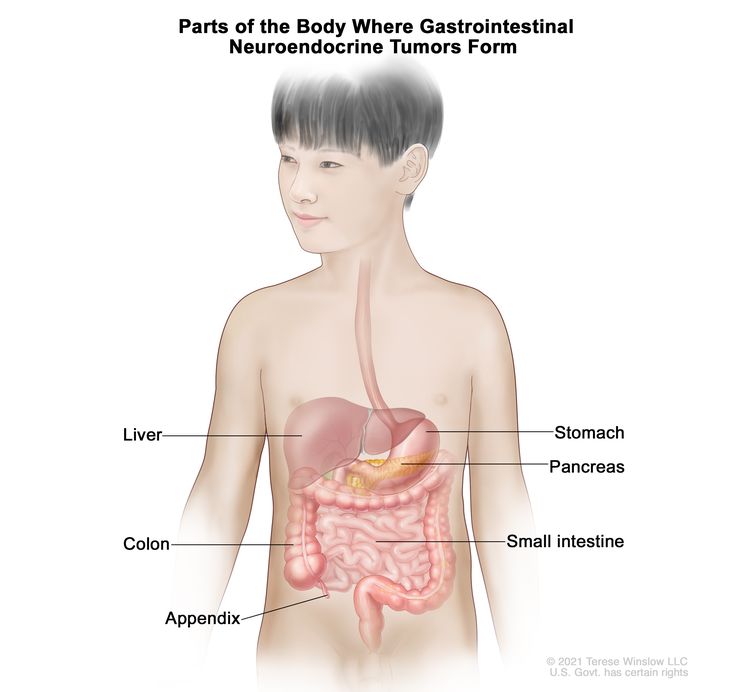

Childhood gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor (also called gastrointestinal carcinoid tumor) is a rare cancer that develops in neuroendocrine cells. These cells have features of both nerve cells and hormone-producing cells and are found throughout the body, most often in the chest and abdomen. In the digestive tract, these cells help control digestion and the movement of food through the stomach and intestines.

In children, these tumors most often form in the appendix, a small pouch connected to the beginning of the large intestine. They are usually found by accident during surgery to remove the appendix. Appendiceal neuroendocrine tumors in children tend to grow slowly and almost never spread to other parts of the body.

Rarely, neuroendocrine tumors can also form in other parts of the digestive system, such as the stomach, intestines, pancreas, or liver. Cancer that forms in these areas have a higher chance of spreading and may need more treatment.

Causes and risk factors for childhood gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors

Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors in children are caused by certain changes to the way gastrointestinal neuroendocrine cells function, especially how they grow and divide into new cells. Often, the exact cause of these changes is unknown. Learn more about how cancer develops at What Is Cancer?

A risk factor is anything that increases the chance of getting a disease. Children with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) or von Hipple Lindau (VHL) syndrome may have a higher risk of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors. Talk with your child's doctor if you think your child may be at risk.

Genetic counseling for children with gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor that is not in the appendix

It may not be clear from the family medical history whether your child's gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor is part of an inherited condition. Genetic counseling can assess the likelihood that your child's cancer is inherited and whether genetic testing is needed. Genetic counselors and other specially trained health professionals can discuss your child's diagnosis and your family's medical history to help you understand:

- the options for testing for changes in the MEN1 and VHL genes

- the risk of other cancers for your child

- the risk of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor or other cancers for your child's siblings

- the risk and benefits of learning genetic information

Genetic counselors can also help you cope with your child's genetic testing results, including how to discuss the results with family members. They can also advise you about whether other members of your family should receive genetic testing.

Learn about Genetic Testing for Inherited Cancer Risk.

Symptoms of childhood gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor

The symptoms of a gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor depend on where the tumor forms in the abdomen. It's important to check with your child's doctor if your child has any symptoms below.

Neuroendocrine tumors in the appendix are often found during an appendectomy for appendicitis. Appendicitis is a medical emergency that can cause:

- abdominal pain, especially on the lower right side of the abdomen

- fever

- nausea and vomiting

- diarrhea

A gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor that is not in the appendix may release hormones and other substances. Carcinoid syndrome occurs when a neuroendocrine tumor in the digestive tract releases the hormone serotonin and other substances. It may cause:

- redness and a warm feeling in the face, neck, and upper chest

- a fast heartbeat

- trouble breathing

- sudden drop in blood pressure which can cause restlessness, confusion, weakness, dizziness, and pale, cool, and clammy skin

- diarrhea

These symptoms may be caused by problems other than a gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor. The only way to know is for your child to see a doctor.

Tests to diagnose childhood gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor

If your child has symptoms that suggest a gastrointestinal tumor, the doctor will need to find out if they are due to cancer or another problem. The doctor will ask when the symptoms started and how often your child has been having them. The doctor will also ask about your child's personal and family medical history and do a physical exam. Depending on these results, they may recommend other tests. If your child is diagnosed with gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor, the results of these tests will help plan treatment.

The tests used to diagnose gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor may include:

Blood chemistry study

Blood chemistry study uses a blood sample to measure the amounts of certain substances released into the blood by organs and tissues in the body. An unusual amount of a substance can be a sign of disease.

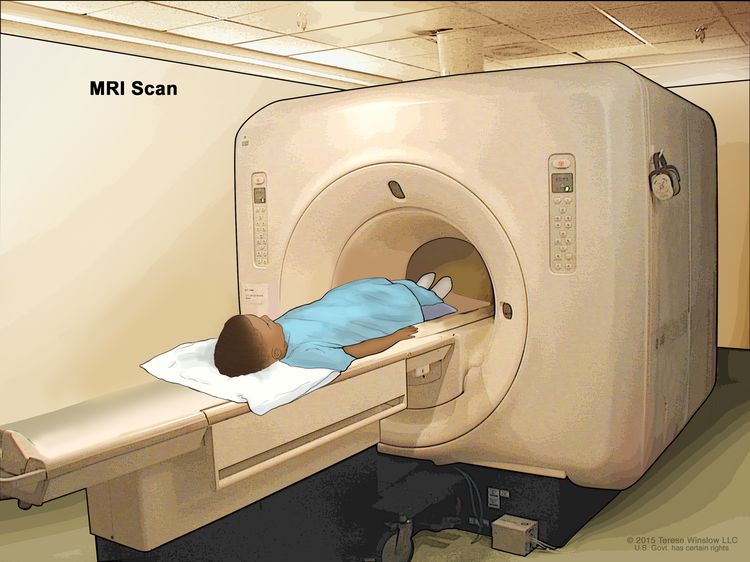

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas in the body. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI).

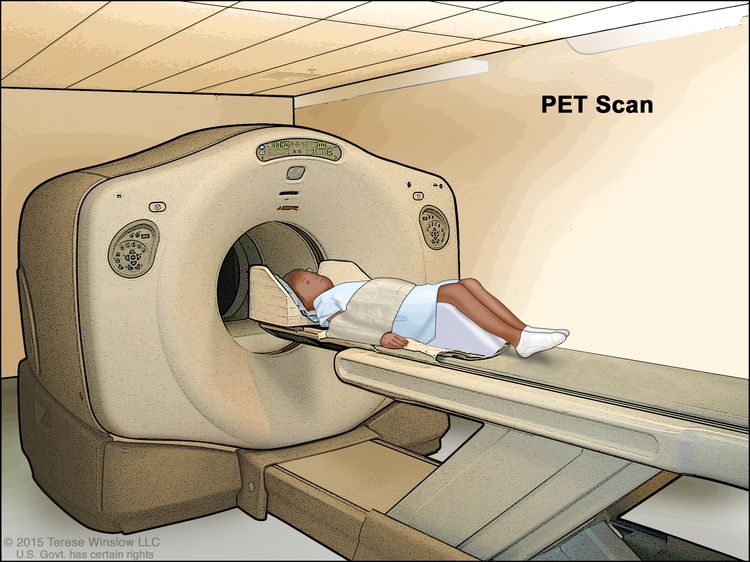

PET scan

PET scan (positron emission tomography scan) uses a small amount of radioactive sugar (also called radioactive glucose) that is injected into a vein. The PET scanner rotates around the body and makes pictures of where sugar is being used by the body. Cancer cells show up brighter in the pictures because they are more active and take up more sugar than normal cells do.

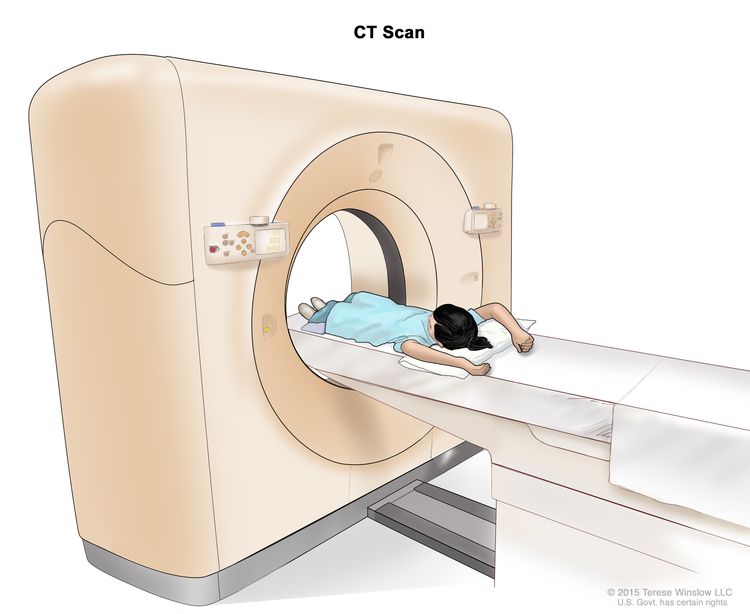

CT scan

CT scan (CAT scan) uses a computer linked to an x-ray machine to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. The pictures are taken from different angles and are used to create 3-D views of tissues and organs. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography. Learn more about Computed Tomography (CT) Scans and Cancer.

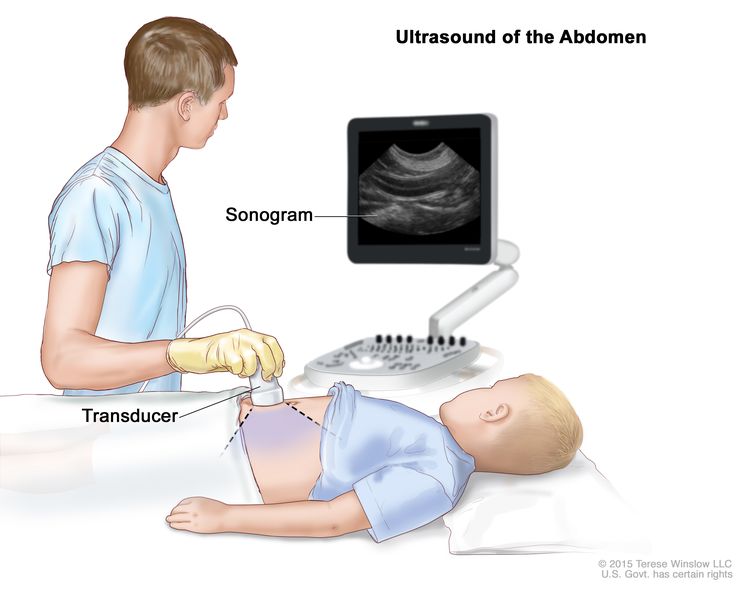

Ultrasound

Ultrasound uses high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) that bounce off internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram.

24-hour urine test

A 24-hour urine test collects urine for 24 hours to measure the amounts of certain substances, such as hormones. An unusual amount of a substance can be a sign of disease in the organ or tissue that makes it. The urine sample is checked to see if it contains 5-HIAA (a breakdown product of the hormone serotonin which may be made by neuroendocrine tumors). This test is used to help diagnose carcinoid syndrome.

Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy

Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy is a type of radionuclide scan that may be used to find tumors. A very small amount of radioactive octreotide (a hormone that attaches to tumors) is injected into a vein and travels through the blood. The radioactive octreotide attaches to the tumor and a special camera that detects radioactivity is used to show where the tumors are in the body. This procedure is also called octreotide scan and SRS.

Getting a second opinion

You may want to get a second opinion to confirm your child’s cancer diagnosis and treatment plan. If you seek a second opinion, you will need to get medical test results and reports from the first doctor to share with the second doctor. The second doctor will review the genetic test report, pathology report, slides, and scans. This doctor may agree with the first doctor, suggest changes to the treatment plan, or provide more information about your child’s cancer.

To learn more about choosing a doctor and getting a second opinion, visit Finding Cancer Care. You can contact NCI's Cancer Information Service via chat, email, or phone (both in English and Spanish) for help finding a doctor or hospital that can provide a second opinion. For questions you might want to ask at your appointments, visit Questions to Ask Your Doctor About Cancer.

Types of treatment for childhood gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor

Who treats children with gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor?

A pediatric oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating children with cancer, oversees treatment of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor. The pediatric oncologist works with other pediatric health care providers who are experts in treating children with cancer and who specialize in certain areas of medicine. Other specialists may include:

Treatment options

There are different types of treatment for children and adolescents with a gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor. You and your child's cancer care team will work together to decide treatment. Many factors will be considered, such as your child's overall health and whether the cancer is newly diagnosed or has come back.

Your child's treatment plan will include information about the cancer, the goals of treatment, treatment options, and the possible side effects. It will be helpful to talk with your child's cancer care team before treatment begins about what to expect. For help every step of the way, visit our booklet, Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents.

Types of treatment your child might have include:

Surgery

Surgery to remove the tumor is the only treatment needed for neuroendocrine tumor in the appendix. Surgery is also used alone or with other therapies to treat neuroendocrine tumors outside the appendix.

Embolization

Embolization is a treatment in which contrast dye and particles are injected into the hepatic artery through a catheter (thin tube). The particles block the artery, cutting off blood flow to the tumor. Sometimes a small amount of a radioactive substance is attached to the particles. Most of the radiation is trapped near the tumor to kill the cancer cells. This is called radioembolization.

Radioactive drug

A radioactive drug contains a radioactive substance and is used to diagnose or treat disease, including cancer. Lutetium Lu 177-dotatate is a radioactive drug used to treat gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor.

Clinical trials

For some children, joining a clinical trial may be an option. There are different types of clinical trials for childhood cancer. For example, a treatment trial tests new treatments or new ways of using current treatments. Supportive care and palliative care trials look at ways to improve quality of life, especially for those who have side effects from cancer and its treatment.

You can use the clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials accepting participants. The search allows you to filter trials based on the type of cancer, your child's age, and where the trials are being done. Clinical trials supported by other organizations can be found on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

Learn more about clinical trials, including how to find and join one, at Clinical Trials Information for Patients and Caregivers.

Treatment of childhood gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor

Treatment of neuroendocrine tumor in the appendix in children is surgery to remove the appendix.

Treatment of neuroendocrine tumor in the large intestine, pancreas, or stomach is usually surgery.

Treatment of neuroendocrine tumor that cannot be removed by surgery, multiple tumors, or tumors that have spread may include:

- embolization

- radioactive drug (lutetium Lu 177-dotatate)

If the cancer comes back after treatment, your child's doctor will talk with you about what to expect and possible next steps. There might be treatment options that may shrink the cancer or control its growth. If there are no treatments, your child can receive care to control symptoms from cancer so they can be as comfortable as possible.

Prognostic factors for childhood gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor

If your child has been diagnosed with a gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor, you likely have questions about how serious the cancer is and your child's chances of survival. The likely outcome or course of a disease is called prognosis.

Prognosis depends on:

- where the tumor first formed in the body

- the size of the tumor

- whether the tumor has spread to other parts of the body

- whether the tumor is newly diagnosed or has recurred (come back)

The prognosis for neuroendocrine tumors in the appendix in children is usually excellent after surgery to remove the tumor. Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors that are not in the appendix may be larger or have spread to other parts of the body at the time of diagnosis and usually do not respond well to chemotherapy. Larger tumors are more likely to recur (come back).

No two people are alike, and responses to treatment can vary greatly. Your child's cancer care team is in the best position to talk with you about your child's prognosis.

Side effects and late effects of treatment

Cancer treatments can cause side effects. Which side effects your child might have depends on the type of treatment they receive, the dose, and how their body reacts. Talk with your child's treatment team about which side effects to look for and ways to manage them.

To learn more about side effects that begin during treatment for cancer, visit Side Effects.

Problems from cancer treatment that begin 6 months or later after treatment and continue for months or years are called late effects. Late effects of cancer treatment may include:

- physical problems

- changes in mood, feelings, thinking, learning, or memory

- second cancers (new types of cancer) or other problems

Some late effects may be treated or controlled. It is important to talk with your child's doctors about the possible late effects caused by some treatments. Learn more about Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer.

Follow-up care

As your child goes through treatment, they will have follow-up tests or check-ups. Some of the tests that were done to diagnose the cancer may be repeated to see how well the treatment is working. Decisions about whether to continue, change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests.

Some of the tests will continue to be done from time to time after treatment has ended. The results of these tests can show if your child's condition has changed or if the cancer has recurred (come back).

To learn more about follow-up tests, visit Tests to diagnose childhood gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumor.

Coping with your child's cancer

When your child has cancer, every member of the family needs support. Taking care of yourself during this difficult time is important. Reach out to your child’s treatment team and to people in your family and community for support. To learn more, visit Support for Families: Childhood Cancer and the booklet Children with Cancer: A Guide for Parents.

Related resources

For more childhood cancer information and other general cancer resources, visit:

About This PDQ Summary

About PDQ

Physician Data Query (PDQ) is the National Cancer Institute's (NCI's) comprehensive cancer information database. The PDQ database contains summaries of the latest published information on cancer prevention, detection, genetics, treatment, supportive care, and complementary and alternative medicine. Most summaries come in two versions. The health professional versions have detailed information written in technical language. The patient versions are written in easy-to-understand, nontechnical language. Both versions have cancer information that is accurate and up to date and most versions are also available in Spanish.

PDQ is a service of the NCI. The NCI is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH is the federal government’s center of biomedical research. The PDQ summaries are based on an independent review of the medical literature. They are not policy statements of the NCI or the NIH.

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary has current information about the treatment of childhood gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors. It is meant to inform and help patients, families, and caregivers. It does not give formal guidelines or recommendations for making decisions about health care.

Reviewers and Updates

Editorial Boards write the PDQ cancer information summaries and keep them up to date. These Boards are made up of experts in cancer treatment and other specialties related to cancer. The summaries are reviewed regularly and changes are made when there is new information. The date on each summary ("Updated") is the date of the most recent change.

The information in this patient summary was taken from the health professional version, which is reviewed regularly and updated as needed, by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board.

Clinical Trial Information

A clinical trial is a study to answer a scientific question, such as whether one treatment is better than another. Trials are based on past studies and what has been learned in the laboratory. Each trial answers certain scientific questions in order to find new and better ways to help cancer patients. During treatment clinical trials, information is collected about the effects of a new treatment and how well it works. If a clinical trial shows that a new treatment is better than one currently being used, the new treatment may become "standard." Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Clinical trials can be found online at NCI's website. For more information, call the Cancer Information Service (CIS), NCI's contact center, at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237).

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. The content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text. It cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless the whole summary is shown and it is updated regularly. However, a user would be allowed to write a sentence such as “NCI’s PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks in the following way: [include excerpt from the summary].”

The best way to cite this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Childhood Gastrointestinal Neuroendocrine Tumors. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/gi-neuroendocrine-tumors/patient/child-gi-neuroendocrine-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>.

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use in the PDQ summaries only. If you want to use an image from a PDQ summary and you are not using the whole summary, you must get permission from the owner. It cannot be given by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the images in this summary, along with many other images related to cancer can be found in Visuals Online. Visuals Online is a collection of more than 3,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

The information in these summaries should not be used to make decisions about insurance reimbursement. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website’s E-mail Us.