Lymphedema (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version

Overview

Lymphedema occurs when disruption of normal lymphatic drainage leads to accumulation of protein-rich lymph fluid in the interstitial space. Cancer survivors who experience lymphedema report poor physical functioning, impaired ability to engage in normal activities of daily living, and increased psychological distress.[1-5]

Estimates of the prevalence of lymphedema vary widely due to differences in the type of cancer, measurement methods, diagnostic criteria, and timing of evaluations relative to cancer diagnosis and treatment. In a survey conducted in 2006 and 2010, 6,593 cancer survivors were asked to identify ongoing concerns. Approximately 20% of respondents reported concerns related to lymphedema. Of these individuals, 50% to 60% reported receiving care for lymphedema.[6] These results align reasonably well with a survey study of women survivors of ovarian, endometrial, and colorectal cancers, who met criteria for lymphedema based on a validated survey that demonstrated a point prevalence of 37%, 33%, and 31%, respectively.[3] Similarly, a randomized intervention study in women with breast cancer demonstrated, by limb volume measurements or physician diagnosis, that 42% of subjects had lymphedema at 18 months after surgery.[7][Level of evidence: I]

Lymphedema is a common delayed effect of cancer treatment that negatively impacts survivors' quality of life. This summary reviews the anatomy of the lymphatic system, the pathophysiology of lymphedema secondary to cancer, and epidemiology. The summary also provides clinicians with information related to risk factors, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. The summary does not deal with congenital lymphedema or lymphedema not related to cancer.

In this summary, unless otherwise stated, evidence and practice issues as they relate to adults are discussed. The evidence and application to practice related to children may differ significantly from information related to adults. When specific information about the care of children is available, it is summarized under its own heading.

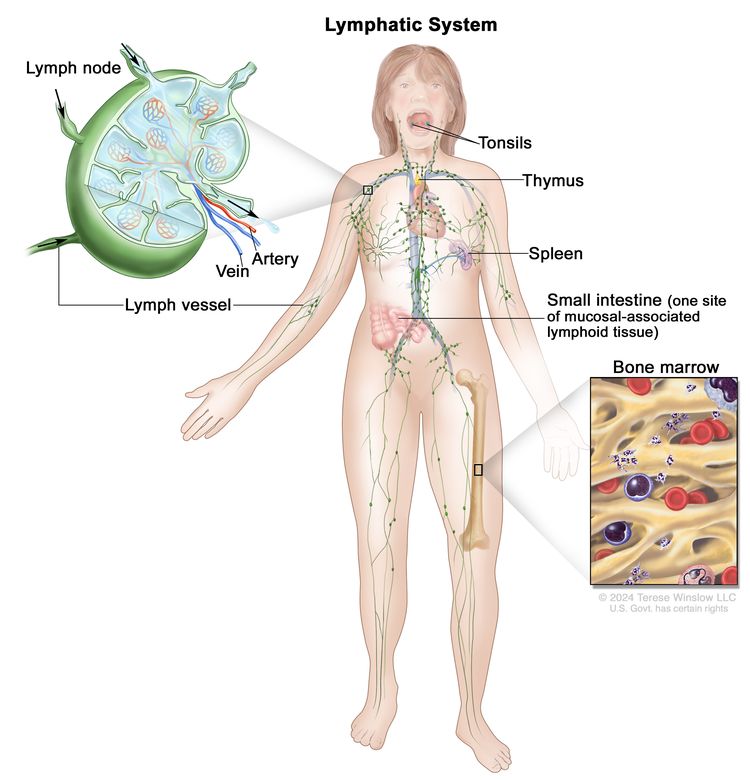

Anatomy of the Lymphatic System

The human lymphatic system generally includes superficial or primary lymphatic vessels that form a complex dermal network of capillary-like channels. Primary lymphatic vessels lack muscular walls and do not have valves. They drain into larger, secondary lymphatic vessels located in the subdermal space. Secondary lymphatic vessels run parallel to the superficial veins and drain into deeper lymphatic vessels located in the subcutaneous fat adjacent to the fascia. Unlike the primary vessels, the secondary and deeper lymphatic vessels have muscular walls and numerous valves to accomplish active and unidirectional lymphatic flow.

An intramuscular system of lymphatic vessels that parallels the deep arteries and drains the muscular compartment, joints, and synovium also exists. The superficial and deep lymphatic systems probably function independently, except in abnormal states, although there is evidence that they communicate near lymph nodes.[8] Lymph drains from the lower limbs into the lumbar lymphatic trunk. The lumbar lymphatic trunk joins the intestinal lymphatic trunk and cisterna chyli to form the thoracic duct, which empties into the left subclavian vein. The lymphatic vessels of the left arm drain into the left subclavian lymphatic trunk and then into the left subclavian vein. The lymphatic vessels of the right arm drain into the right subclavian lymphatic trunk and then into the right subclavian vein.

Pathophysiology of Lymphedema

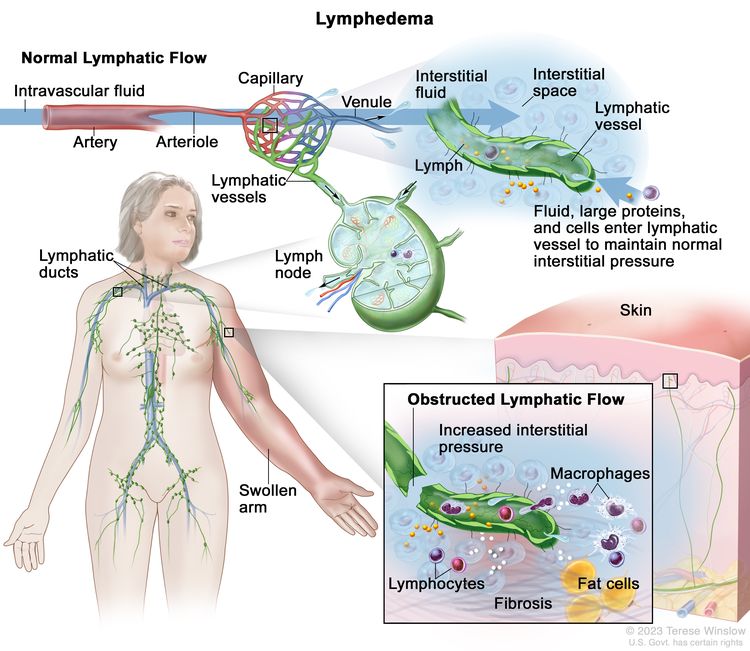

Body fluids can be discussed in terms of their composition and the specific fluid compartment where they are located. Intracellular fluid includes all fluid enclosed by the plasma membranes of cells. Extracellular fluid (ECF) surrounds all cells in the body. ECF has two primary constituents: intravascular plasma and the interstitial fluid that surrounds all cells not in the plasma. Lymphedema is the abnormal accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the interstitial space that is accompanied by inflammation and, eventually, fibrosis.

The formation of interstitial fluid comes from the movement of intravascular fluid across the capillary membranes due to arteriolar blood pressure. Much of the interstitial fluid returns to the intravascular fluid via the postcapillary venules. The dynamics of fluid production are influenced by arterial and venous hydrostatic pressures, tissue pressure, oncotic pressures of the intravascular and interstitial fluid, and membrane permeability. Normally, the dynamics favor a net gain of interstitial fluid, with the excess removed via lymphatic channels. Because lymphatic vessels often lack a basement membrane, they can resorb molecules too large for venous uptake as well. In short, the lymphatic system controls the pressure, volume, and composition of the interstitial fluid.

Lymphatic obstruction leads to increased interstitial fluid, which often contains large proteins and cellular debris. Through mechanisms not fully understood, the increased interstitial fluid induces inflammation, destruction or sclerosis of the lymphatic vessels, fibrosis, and, ultimately, adipose tissue hypertrophy.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Accurate estimates of the incidence and prevalence of lymphedema are difficult to provide, due in part to differences in the definition of lymphedema (e.g., patient self-reports vs. objective volume measurements) and the timing of assessment for lymphedema relative to cancer treatment. Other factors are differences in surgical techniques related to the type of lymph node dissection or the total dose, fractions, and field of radiation administered.

Common risk factors for developing lymphedema include the following:

- Extent of local surgery.

- Anatomical location of lymph node dissection.

- Radiation to lymph nodes.

- Localized infection or delayed wound healing.

- Tumor causing lymphatic obstruction of the anterior cervical, thoracic, axillary, pelvic, or abdominal nodes.

- Intrapelvic or intra-abdominal tumors that involve or directly compress lymphatic vessels and/or the cisterna chyli and thoracic duct.

- Having a higher disease stage.

- Overweight (body mass index [BMI] ≥25 kg/m2) or obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2).[9]

- Black race and Hispanic ethnicity.[10]

- Rurality.[10]

References

- Ridner SH: Quality of life and a symptom cluster associated with breast cancer treatment-related lymphedema. Support Care Cancer 13 (11): 904-11, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dunberger G, Lindquist H, Waldenström AC, et al.: Lower limb lymphedema in gynecological cancer survivors--effect on daily life functioning. Support Care Cancer 21 (11): 3063-70, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Zhang X, McLaughlin EM, Krok-Schoen JL, et al.: Association of Lower Extremity Lymphedema With Physical Functioning and Activities of Daily Living Among Older Survivors of Colorectal, Endometrial, and Ovarian Cancer. JAMA Netw Open 5 (3): e221671, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Pyszel A, Malyszczak K, Pyszel K, et al.: Disability, psychological distress and quality of life in breast cancer survivors with arm lymphedema. Lymphology 39 (4): 185-92, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gjorup CA, Groenvold M, Hendel HW, et al.: Health-related quality of life in melanoma patients: Impact of melanoma-related limb lymphoedema. Eur J Cancer 85: 122-132, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Beckjord EB, Reynolds KA, van Londen GJ, et al.: Population-level trends in posttreatment cancer survivors' concerns and associated receipt of care: results from the 2006 and 2010 LIVESTRONG surveys. J Psychosoc Oncol 32 (2): 125-51, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Paskett ED, Le-Rademacher J, Oliveri JM, et al.: A randomized study to prevent lymphedema in women treated for breast cancer: CALGB 70305 (Alliance). Cancer 127 (2): 291-299, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Horsley JS, Styblo T: Lymphedema in the postmastectomy patient. In: Bland KI, Copeland EM, eds.: The Breast: Comprehensive Management of Benign and Malignant Diseases. Saunders, 1991, pp 701-6.

- McLaughlin SA, Brunelle CL, Taghian A: Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: Risk Factors, Screening, Management, and the Impact of Locoregional Treatment. J Clin Oncol 38 (20): 2341-2350, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Montagna G, Zhang J, Sevilimedu V, et al.: Risk Factors and Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Patients With Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema. JAMA Oncol 8 (8): 1195-1200, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

Disease-Specific Lymphedema

Breast Cancer

A systematic review found the prevalence of lymphedema to be 21.4% (14.9%–29.8%) in patients with breast cancer.[1] The incidence increased for up to 2 years after breast cancer diagnosis or surgery, and it was higher in women who underwent axillary lymph node dissection versus sentinel lymph node biopsy (19.9% vs. 5.6%). As a result, omission of axillary dissection in women with an involved sentinel lymph node is now an accepted practice. This practice is a result of a phase III randomized study (ACOSOG-Z0011) that showed no difference in overall survival in women who did not undergo a complete axillary dissection, compared with those who did.[2] Additional risk factors for lymphedema development included greater number of lymph nodes dissected, having a mastectomy, and overweight or obesity.[1,3] In a prospective study of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by axillary lymph node dissection (ACOSOG-Z1071), the incidence of lymphedema after a median follow-up of 3 years was 37.8% (95% confidence interval [CI], 33.1%–43.2%). Increasing body mass index (BMI) (hazard ratio [HR], 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01–1.06), duration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (HR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.01–2.17), number of lymph nodes removed, and number of involved lymph nodes were associated with lymphedema symptoms.[4]

Several risk factors for breast cancer–related lymphedema (BCRL) were demonstrated in a study using data from a 2-year, prospective observational study of 304 patients with breast cancer who had axillary lymph node dissection and radiation therapy. The cumulative incidence of lymphedema was measured by a more than 10% increase in arm volume, and univariate and multivariable analyses were performed. On multivariable analysis, Black race and Hispanic ethnicity (odds ratio [OR], 3.88; 95% CI, 2.14–7.08, and OR, 3.01; 95% CI, 1.10–7.62, respectively; P < .001 for each), receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (OR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.16–3.95; P = .01), older age (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02–1.07 per 1-year increase; P = .001), and a longer follow-up interval (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.30–1.90 per 6-month increase; P < .001) were independently associated with an increased risk.[5][Level of evidence: II]

Another study examined risk factors for BCRL related to treatment, comorbidities, and lifestyle in 918 women enrolled in a Prospective Surveillance and Early Intervention (PSEI) trial. Women were randomly assigned to either bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS) or tape measurement (TM).[6] In a secondary analysis, risk factors were used to test for factor associations with outcomes (no lymphedema, subclinical lymphedema, progression to chronic lymphedema after intervention, progression to chronic lymphedema without intervention). Factors associated with BCRL risk included axillary lymph node dissection (P < .001), taxane-based chemotherapy (P < .001), regional nodal irradiation (P ≤ .001), BMI greater than 30 (P = .002), and rurality (P = .037).[6]

Gynecological Cancers

A cohort study supports the evidence that a significant proportion of women experience lower-limb lymphedema after treatment of gynecological cancer or colorectal cancer. The highest prevalence (36.5%) among ovarian cancer survivors, followed by endometrial cancer survivors (32.5%) and colorectal cancer survivors (31.4%).[7]

In one study, 802 of 1,774 women diagnosed with a gynecological cancer between 1999 and 2004 responded to a survey about lymphedema.[8] Twenty-five percent of the respondents reported lower-extremity edema; 10% had been diagnosed with lymphedema. Most respondents (75%) had been diagnosed with these conditions within the first year of a cancer diagnosis. Women with vulvar cancer were most likely to have symptoms (36%). Lymph node dissection increased the risk of symptoms in women with cervical cancer but not uterine cancer. The range of symptoms included heavy legs, pain, and skin tightness. Standing all day, long-distance travel, and hot weather were precipitating conditions. The most common treatments were compression garments, massage, and lymphatic exercises. The findings related to high prevalence in patients with vulvar cancer and occurrence of symptoms within the first year have been verified.[9]

Serial limb volume measurements were obtained from a cohort of women who underwent a lymph node dissection for vulvar (n = 42), endometrial (n = 734), or cervical (n = 138) cancer 4 to 6 weeks after surgery and then every 3 months.[10] The incidence of an increase in limb volume of more than 10% was 43% for vulvar cancer, 34% for endometrial cancer, and 33% for cervical cancer. The incidence of severe lymphedema (>40% increase in volume) was less than 2% in all cohorts. The peak incidence was at the 4- to 6-week time point, but new cases were identified at all time points. The risk-factor analysis identified a reduced risk in women older than 65 years and a higher risk in women who had more than eight lymph nodes removed in the endometrial cohort.

Head and Neck Cancer

Patients with head and neck cancer are susceptible to external and internal lymphedema. External lymphedema typically presents with submental edema or lower neck swelling. Internal lymphedema is more widely distributed in the anatomical regions of the oropharynx. In a small cross-sectional study with video-assisted examinations, 59 of 61 patients had some degree of lymphedema.[11][Level of evidence: II] Sixty-one percent of the patients had only internal lymphedema, 35% had internal and external lymphedema, and 4% had only external lymphedema. Postoperative radiation therapy was a risk factor for combined lymphedema. Chemotherapy was a risk factor for patients with internal lymphedema only.

Melanoma

One single-center, cross-sectional study reported on lymphedema after either sentinel lymph node biopsy or lymph node dissection in 435 patients who were treated for melanoma between 1997 and 2015.[12] The authors reported a lymphedema prevalence of 25%. Forty-eight patients (44%) had International Society of Lymphology (ISL) stage I lymphedema (pitting edema), and 61 patients (56%) had ISL stage II or III lymphedema. Multivariate analyses identified as potential predictive factors the primary site of disease on the affected limb, inguinal surgery, and persistent pain at the site of lymph node surgery. Limb cellulitis was a risk factor for ISL stage II and III lymphedema. The same investigators also reported on health-related quality of life in an earlier publication. In another smaller, single-institution, retrospective study of 66 patients who underwent therapeutic nodal dissection, the rate of permanent lymphedema for inguinal node dissection was 38%, compared with 12% for axillary node dissection.[13] Another potentially relevant variable is the type of dissection. A 2017 systematic review did not find an appreciable difference between the rate of lymphedema after therapeutic lymphadenectomy and completion of lymph node sampling after a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy.[14] In both instances, the rate was around 20%.

Prostate Cancer

There are few studies of lymphedema after prostate cancer therapy. A small cross-sectional survey of men who underwent radical prostatectomy reported that 19 of 54 respondents (35.2%) had bilateral lower-extremity lymphedema.[15][Level of evidence: II] Of note, 25 respondents reported that they had received manual lymphatic drainage therapy. Men who did not experience regression experienced more distress related to physical and mental functioning than those who did. An elevated BMI and poor general health were risk factors for lymphedema.

Sarcoma

One study measured patient demographics, surgical outcomes data, functional outcomes, and lymphedema severity with a validated scale for 289 patients who underwent limb preservation surgery of an extremity sarcoma between 2000 and 2007.[16] The mean time from surgery was 35 months (range, 12–60 months). Eighty-three patients had some degree of lymphedema, including 58 with mild but definite swelling, 22 with moderate swelling, and 3 with considerable swelling. No patients had grade 4 or very severe swelling with shiny skin and skin cracking. Univariate analysis demonstrated that radiation therapy, tumor size, and tumor depth correlated with severity. The location of the sarcoma (upper or lower extremity), lymph node dissection (yes or no), and BMI did not correlate with severity. Multivariable analysis demonstrated that tumor size was the only independent predictor.

References

- DiSipio T, Rye S, Newman B, et al.: Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 14 (6): 500-15, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Giuliano AE, Ballman KV, McCall L, et al.: Effect of Axillary Dissection vs No Axillary Dissection on 10-Year Overall Survival Among Women With Invasive Breast Cancer and Sentinel Node Metastasis: The ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 318 (10): 918-926, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- McLaughlin SA, Brunelle CL, Taghian A: Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: Risk Factors, Screening, Management, and the Impact of Locoregional Treatment. J Clin Oncol 38 (20): 2341-2350, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Armer JM, Ballman KV, McCall L, et al.: Factors Associated With Lymphedema in Women With Node-Positive Breast Cancer Treated With Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Axillary Dissection. JAMA Surg 154 (9): 800-809, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Montagna G, Zhang J, Sevilimedu V, et al.: Risk Factors and Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Patients With Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema. JAMA Oncol 8 (8): 1195-1200, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Koelmeyer LA, Gaitatzis K, Dietrich MS, et al.: Risk factors for breast cancer-related lymphedema in patients undergoing 3 years of prospective surveillance with intervention. Cancer 128 (18): 3408-3415, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Zhang X, McLaughlin EM, Krok-Schoen JL, et al.: Association of Lower Extremity Lymphedema With Physical Functioning and Activities of Daily Living Among Older Survivors of Colorectal, Endometrial, and Ovarian Cancer. JAMA Netw Open 5 (3): e221671, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Beesley V, Janda M, Eakin E, et al.: Lymphedema after gynecological cancer treatment : prevalence, correlates, and supportive care needs. Cancer 109 (12): 2607-14, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ryan M, Stainton MC, Slaytor EK, et al.: Aetiology and prevalence of lower limb lymphoedema following treatment for gynaecological cancer. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 43 (2): 148-51, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Carter J, Huang HQ, Armer J, et al.: GOG 244 - The LymphEdema and Gynecologic cancer (LEG) study: The association between the gynecologic cancer lymphedema questionnaire (GCLQ) and lymphedema of the lower extremity (LLE). Gynecol Oncol 155 (3): 452-460, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jeans C, Brown B, Ward EC, et al.: Comparing the prevalence, location, and severity of head and neck lymphedema after postoperative radiotherapy for oral cavity cancers and definitive chemoradiotherapy for oropharyngeal, laryngeal, and hypopharyngeal cancers. Head Neck 42 (11): 3364-3374, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gjorup CA, Groenvold M, Hendel HW, et al.: Health-related quality of life in melanoma patients: Impact of melanoma-related limb lymphoedema. Eur J Cancer 85: 122-132, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Deban M, Vallance P, Jost E, et al.: Higher Rate of Lymphedema with Inguinal versus Axillary Complete Lymph Node Dissection for Melanoma: A Potential Target for Immediate Lymphatic Reconstruction? Curr Oncol 29 (8): 5655-5663, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Moody JA, Botham SJ, Dahill KE, et al.: Complications following completion lymphadenectomy versus therapeutic lymphadenectomy for melanoma - A systematic review of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol 43 (9): 1760-1767, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Neuberger M, Schmidt L, Wessels F, et al.: Onset and burden of lower limb lymphedema after radical prostatectomy: a cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer 30 (2): 1303-1313, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Friedmann D, Wunder JS, Ferguson P, et al.: Incidence and Severity of Lymphoedema following Limb Salvage of Extremity Soft Tissue Sarcoma. Sarcoma 2011: 289673, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

Diagnosis of Lymphedema

Signs, Symptoms, and Physical Examination

Lymphedema is typically evident by clinical findings such as unilateral, nonpitting edema, usually with involvement of the digits, in a patient with known risk factors (e.g., a breast cancer patient with previous axillary dissection). Other causes of limb swelling, including deep venous thrombosis, malignancy, and infection, should be considered in the differential diagnosis and excluded with appropriate studies, if indicated.

Lymphedema in patients with head and neck cancer can present slightly differently. External lymphedema does show swelling in the head and neck area, but internal lymphedema does not. Instead, patients with lymphedema related to internal head and neck cancer can present with complaints of voice changes, dysphagia, and possible difficulty breathing.

Diagnostic Testing

Limb measurements

The wide variety of methods for evaluating limb volume and lack of standardization make it difficult for the clinician to assess the at-risk limb. Options include water displacement, tape measurement, infrared scanning, and bioelectrical impedance measures.[1]

The most common method for diagnosing upper-extremity lymphedema is circumferential upper-extremity measurement using specific anatomical landmarks.[2] Arm circumference measurements are used to estimate volume differences between the affected and unaffected arms. Sequential measurements are taken at four points on both arms: the metacarpal-phalangeal joints, the wrist, 10 cm distal to the lateral epicondyles, and 15 cm proximal to the lateral epicondyles. Differences of 2 cm or more at any point compared with the unaffected arm are considered by some experts to be clinically significant. However, measuring specific differences between arms may have limited clinical relevance because of implications, such as a 3-cm difference between the arm of an obese woman and the arm of a thin woman. In addition, there can be inherent anatomical variations in circumference between the dominant and nondominant limb related to differences in muscle mass. In addition, variations after breast cancer treatment may occur with atrophy of the ipsilateral arm or hypertrophy of the contralateral arm.[3] A small study comparing various methods of assessing upper-limb lymphedema did not show superiority of any one method.[1] Sequential measurements over time, including pretreatment measurements, may prove to be more clinically meaningful.

The water displacement method is another way to evaluate arm edema. A volume difference of 200 mL or more between the affected and opposite arms is typically considered to be a cutoff point to define lymphedema.[4]

Magnetic resonance lymphography (MRL)

This technique involves the intracutaneous injection of a paramagnetic contrast agent, followed by imaging of the lymphatic anatomy, dermal flow patterns, and adjacent fatty tissue. One study of 50 women with breast cancer–related lymphedema compared the lymphatic vessel morphology in their affected and unaffected arms.[5][Level of evidence: II] The lymphedema was staged according to the ISL's 2016 staging system.[6][Level of evidence: IV] In all patients, the lymph fluid was in the subcutis but not the subfascial compartment of the affected arm. In stage I patients, the lymphatics were tortuous and dilated, but there was no dermal backflow or regeneration of the lymphatics. In stage II patients, there was soft tissue fibrosis and adipose tissue hypertrophy. The lymphatics were tortuous and dilated, with areas of dermal backflow and regeneration. In stage III patients, the lymphatics were unrecognizable, and there was confluent dermal backflow. The soft tissue fibrosis was more advanced. MRL is safe, feasible, and provides high anatomical detail. However, its role in lymphedema diagnosis remains to be determined.

Staging and grading of severity

The staging system of the ISL reflects likely changes over time based on the pathophysiology of lymphedema. The stages include the following:

- Stage 0: This stage, referred to as subclinical lymphedema, is characterized by impaired lymph flow.

- Stage I: This stage is spontaneously reversible and typically marked by pitting edema, an increase in upper-extremity girth, and heaviness.

- Stage II: This moderate stage is characterized by a spongy consistency of the tissue without signs of pitting edema. Tissue fibrosis can then cause the limbs to harden and increase in size.[2] The swelling at this stage is mostly fluid.

- Stage III: In the most advanced stage,[2] swelling is mostly secondary to fat hypertrophy, so there is no pitting edema.

The severity of lymphedema may be evaluated using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), which was developed for grading adverse events in the context of clinical trials.[7] A key advantage of the CTCAE approach is that it includes both objective measures (interlimb discrepancy) and subjective clinical assessments in diagnosing lymphedema. This approach allows the clinician to address troublesome signs and symptoms that may occur without significant interlimb discrepancy. The CTCAE volume 3 criteria are:

- Grade 1: 5% to 10% interlimb discrepancy in volume or circumference at point of greatest visible difference; swelling or obscuration of anatomical architecture on close inspection; pitting edema.

- Grade 2: More than 10% to 30% interlimb discrepancy in volume or circumference at point of greatest visible difference; readily apparent obscuration of anatomical architecture; obliteration of skin folds; readily apparent deviation from normal anatomical contour.

- Grade 3: More than 30% interlimb discrepancy in volume; lymphorrhea; gross deviation from normal anatomical contour; interference with activities of daily living (ADL).

- Grade 4: Progression to malignancy (e.g., lymphangiosarcoma); amputation indicated; disabling lymphedema.

The fifth version of the CTCAE is more streamlined and does not include limb volumes:[8]

- Grade 1: Trace thickening or faint discoloration.

- Grade 2: Marked discoloration; leathery skin texture; papillary formation; limitation in instrumental ADL.

- Grade 3: Severe symptoms; limitation in self-care ADL.

References

- Ridner SH, Montgomery LD, Hepworth JT, et al.: Comparison of upper limb volume measurement techniques and arm symptoms between healthy volunteers and individuals with known lymphedema. Lymphology 40 (1): 35-46, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bicego D, Brown K, Ruddick M, et al.: Exercise for women with or at risk for breast cancer-related lymphedema. Phys Ther 86 (10): 1398-405, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Petrek JA: Commentary: prospective trial of complete decongestive therapy for upper extremity lymphedema after breast cancer therapy. Cancer J 10 (1): 17-9, 2004.

- Mondry TE, Riffenburgh RH, Johnstone PA: Prospective trial of complete decongestive therapy for upper extremity lymphedema after breast cancer therapy. Cancer J 10 (1): 42-8; discussion 17-9, 2004 Jan-Feb. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sheng L, Zhang G, Li S, et al.: Magnetic Resonance Lymphography of Lymphatic Vessels in Upper Extremity With Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema. Ann Plast Surg 84 (1): 100-105, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Executive Committee: The Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Lymphedema: 2016 Consensus Document of the International Society of Lymphology. Lymphology 49 (4): 170-84, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cheville AL, McGarvey CL, Petrek JA, et al.: The grading of lymphedema in oncology clinical trials. Semin Radiat Oncol 13 (3): 214-25, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- National Cancer Institute: Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), Version 5.0. Bethesda, Md: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, 2017. Available online. Last accessed Dec. 18, 2024.

Prevention and Treatment Options Overview for Lymphedema

There are many potential interventions to reduce the risk of lymphedema or ameliorate its negative consequences. In general, the prevention and treatment interventions may be divided into nonsurgical and surgical approaches. Nonsurgical interventions may be further divided into pharmacological, compressive, or exercise related. Conservative options should be tried and exhausted prior to considering surgical options. This section provides an overview of the various interventions, followed by a more detailed analysis of individual trials based on the type of cancer.

Nonsurgical Options

Compression garments

Compression garments are used to prevent and treat lymphedema by helping to decrease excess formation of interstitial fluid, prevent reflux of lymphatic fluid, and give a barrier to help muscle pumping of fluid up the lymphatic system.[1][Level of evidence: I] Use of flat knit (inelastic) compression garments is better than elastic compression in both the reduction and maintenance phase of stages II and III lymphedema. Inelastic compression garments allow the lymph fluid to be better propelled through the impaired lymphatic system via skeletal muscles. Flat knit garments also have the advantage of applying pressure to firm and soften edema. This pressure is applied at a uniform gradient over a large area. Circular knit garments deliver more pressure in the distal (narrow) part of the garment and are better for venous insufficiency than lymphedema.

Elastic garments are best used for stage I lymphedema and lymphedema that has been converted to stage II after complete decongestive therapy (CDT).

Intermittent external pneumatic compression

This approach should be used in conjunction with compression garments and only if compression is not enough to prevent or treat lymphedema. Concerns regarding the use of intermittent pneumatic compression include the optimum amount of pressure, treatment schedule, and the need for maintenance therapy after the initial reduction in edema.[2][Level of evidence: I] There is a theoretical concern that pressures higher than 60 mm Hg and long-term use may injure lymphatic vessels.

Intermittent external pneumatic compression may improve lymphedema management when used adjunctively with decongestive lymphatic therapy. A small randomized trial of 23 women with new breast cancer–associated lymphedema found an additional significant volume reduction, compared with manual lymphatic drainage alone (45% vs. 26%).[3][Level of evidence: I] Similarly, improvements were also found in the maintenance phase of therapy.

There are several barriers to multidisciplinary decongestive therapy, including cost, inadequate number of trained therapists, and time commitment. In response to these barriers, a group of researchers conducted a trial of a garment under commercial development.[4] The device was fit to patients, who were instructed to use it twice daily for 8 weeks. The investigators randomly assigned subjects to the device group or a wait-list control group. Use of the device was feasible, although most subjects found twice a day too burdensome. The treated subjects reported greater perceived ability to control lymphedema and subjectively had less swelling. There were no serious adverse events related to device usage. The economic costs of advanced compressive devices in lymphedema related to venous insufficiency compared favorably with other compressive techniques in a study of claims data.[5]

Complete decongestive therapy (CDT)

CDT is the standard of care for stage II lymphedema. However, the optimal program has not been established.

CDT has two phases:

- Phase 1—Decongestion/reduction: Skin/wound care, exercise, manual lymphatic drainage, and compression bandages, performed daily for an average of 15 days.

- Phase 2—Maintenance: Skin/wound care, exercise, manual lymphatic drainage as needed, and compression garments.

One study compared manual lymphatic drainage with exercise to treat lymphedema in 39 people with oral cavity cancer.[6] Exercise and manual lymphatic drainage each improved neck range of motion and controlled lymphedema, but they appeared to have a better effect when done together.

A systematic review of manual lymphatic drainage in patients with breast cancer reported on ten studies.[7] Four of the studies reported that manual lymphatic drainage could reduce the incidence of lymphedema (risk ratio, 0.58; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.37–0.93). However, seven of the studies did not show a statistical difference in volumetric changes. They did see a statistical difference in pain control, but not in quality of life.

Physical exercise

Physical exercise may be valuable in the treatment of lymphedema for several reasons, including improvement in lymph flow from muscle contractions and overall cardiovascular function.[8] Conversely, early concerns that exercise may cause harm have not been confirmed.[9,10] Results from a small randomized study suggest that resistance exercise may be offered concurrently with CDT.[11][Level of evidence: I]

A systematic review and meta-analysis reported on 12 prevention and 36 treatment studies of exercise to either prevent or treat cancer-related lymphedema.[8] Most studies (11 of 12 and 32 of 36) enrolled patients with breast cancer. In addition, while most studies investigated some form of resistance training, a few used aerobic exercise alone. The relative risk of developing lymphedema after exercise was 0.90 (95% CI, 0.72–1.13), which was not significant. However, there was a suggested benefit in patients who had more than five lymph nodes removed. In this case, the relative risk was 0.49 (95% CI, 0.28–0.85). For patients in the treatment studies, the standardized mean difference (SMD) in measured outcomes was −0.11 (95% CI, −0.22 to 0.01). The difference compared with the control condition was −0.10 (95% CI, −0.24 to 0.04). Significant differences were detected for discrete outcomes such as pain, upper-body function and strength, lower-body strength, fatigue, and quality of life for those in the exercise group (SMD, 0.3–0.8; P < .05).

The American College of Sports Medicine advises that a supervised, progressive resistance exercise program is safe for patients with or at risk for lymphedema after breast cancer. There is not adequate data about the safety of unsupervised exercise. The safety of exercise in other cancers is unknown.[12][Level of evidence: IV]

Pharmacological therapy

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

The potential benefit of the NSAID ketoprofen on lymphedema was demonstrated in a pair of small trials.[13] The rationale for the use of NSAIDs rests on observations of histopathological inflammatory changes in the affected tissue and a possible relationship between persistent inflammation and impaired lymphangiogenesis. The authors reported an open-label trial, followed by a small placebo-controlled trial. In the latter, 18 patients were treated with placebo and 16 patients were treated with ketoprofen for 4 months. In both trials, ketoprofen treatment led to a significant reduction in skin thickness and an improvement in the histopathological appearance of the skin. In neither trial, however, were there changes in limb volume or skin impedance. These promising early results require verification, given the potential gastrointestinal and cardiovascular risks of NSAIDs.

Surgical Options

The surgical options for the treatment of lymphedema include lymphatico-venous anastomoses (LVA), vascularized lymph node transplantation (VLNT), and reduction of excess tissue volume by excision of liposuction. Several informative reviews describe the surgical decision making involved in selecting patients and the type of operation.[14]

There are limited data to guide the choice between liposuction and microsurgical techniques, and some investigators propose a combined approach.[15] The choice of microsurgical techniques may be aided by imaging and clinical grading of lymphedema severity. One proposal suggests that patients are candidates for LVA if they have partial obstruction seen on lymphoscintigraphy and grade 1 or 2 lymphedema with patent lymphatic ducts observed on indocyanine green lymphography . On the other hand, VLNT may be better for patients exhibiting a total obstruction seen on lymphoscintigraphy and grade 3 or 4 lymphedema without patent lymphatic ducts observed on indocyanine green lymphography.[16]

Lymphatico-venous anastomosis

LVA surgery is typically used in patients with early-grade lymphedema due to difficulties in finding lymphatic vessels. One study reported results for 42 patients with later-grade, lower-extremity lymphedema who underwent preoperative magnetic resonance lymphangiography and ultrasound.[17] The imaging allowed patients to have an average of five successful anastomoses per limb. Clinical outcomes were favorable, raising the possibility of expanded indications for this surgery.

Immediate lymphatic reconstruction at the time of cancer surgery is under active investigation.

Vascularized lymph node transfer

VLNT involves harvesting healthy lymph nodes and their relevant venous and arterial vessels from a donor site and transferring them to the nodal basin of the affected extremity. The proposed mechanisms of action include providing alternative routes of lymphatic drainage and encouraging lymphangiogenesis to provide new lymph vessels to the extremity. At present, there is scant but promising clinical data on the efficacy of VLNT.[18]

A systematic review and summary of patients with breast cancer–related lymphedema who underwent CDT or VLNT [19] examined the evidence that both interventions favorably impact health-related quality of life measures. As anticipated, the data for VLNT was more limited (two studies, 65 patients) than for CDT (14 studies, 569 patients). However, within these limits, the data for VLNT indicated that improvements were commonly seen. The data for CDT were more heterogenous, and the improvement was often less significant. These data give clinicians a reason to consider surgical intervention, although at present the standard practice seems to be CDT.

In a retrospective study of 124 patients with breast cancer–related lymphedema, the degree of improvement in limb circumference and reduction in episodes of cellulitis appeared to be greater in patients who underwent VLNT than in those who underwent LVA.[16] In addition to the usual caution in interpreting retrospective data, the patients who underwent VLNT were ineligible for LVA based on lymphography results. This finding seems to support the use of imaging to guide patient selection. Two small cohort studies of VLNT in patients with breast cancer demonstrated apparent improvements in objective limb measurements and subjective measures of patients’ health-related quality of life.[20][Level of evidence: III]; [21][Level of evidence: II]

Liposuction

Nonpitting chronic lymphedema may be due to adipose tissue hypertrophy. In this case, liposuction to remove the excess adipose tissue is an option. Compression garments are still needed after the liposuction. In addition, excision of the redundant skin after liposuction may be required.[22]

One retrospective study compared the frequency of documented episodes of erysipelas in 130 patients before and after they underwent liposuction.[23] As anticipated, the mean excess arm volume decreased from 1,607 mL to negative 43 mL, and the ratio of affected to normal arm decreased from 1.5 to 1.0. The recorded occurrence of erysipelas decreased from 0.47 to 0.06 attacks per year. Similar results were reported in another study,[24] in which the authors reviewed the charts of 105 women with breast cancer–related lymphedema refractory to compressive therapies who underwent liposuction between 1993 and 2012. Notably, patients had to have nonpitting edema. All women benefited, and the benefit persisted for at least 5 years by measurement.

Laser therapy

Low-level laser therapy (LLT) is a noninvasive technique in which affected tissues receive phototherapy of various wavelengths within 650 to 1,000 nanometers. The role of LLT in the care of people with lymphedema is not established, although a 2017 systematic review found promising evidence.[25] The proposed mechanisms of action include cellular proliferation of macrophages with reduction in fibrosis, reduced inflammatory mediators, lymphangiogenesis, and improved lymphatic flow.[25] In addition, carbon dioxide laser treatment may also lead to clinical improvements, though the data are currently only from small case series.[26] The carbon dioxide laser stimulates remodeling of abnormal collagen by matrix metalloproteinases and dermal neocollagenesis by fibroblasts and supports generation of new lymphatic vessels.

References

- Nadal Castells MJ, Ramirez Mirabal E, Cuartero Archs J, et al.: Effectiveness of Lymphedema Prevention Programs With Compression Garment After Lymphatic Node Dissection in Breast Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Front Rehabil Sci 2: 727256, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dini D, Del Mastro L, Gozza A, et al.: The role of pneumatic compression in the treatment of postmastectomy lymphedema. A randomized phase III study. Ann Oncol 9 (2): 187-90, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Szuba A, Achalu R, Rockson SG: Decongestive lymphatic therapy for patients with breast carcinoma-associated lymphedema. A randomized, prospective study of a role for adjunctive intermittent pneumatic compression. Cancer 95 (11): 2260-7, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ridner SH, Dietrich MS, Deng J, et al.: Advanced pneumatic compression for treatment of lymphedema of the head and neck: a randomized wait-list controlled trial. Support Care Cancer 29 (2): 795-803, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lerman M, Gaebler JA, Hoy S, et al.: Health and economic benefits of advanced pneumatic compression devices in patients with phlebolymphedema. J Vasc Surg 69 (2): 571-580, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tsai KY, Liao SF, Chen KL, et al.: Effect of early interventions with manual lymphatic drainage and rehabilitation exercise on morbidity and lymphedema in patients with oral cavity cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 101 (42): e30910, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lin Y, Yang Y, Zhang X, et al.: Manual Lymphatic Drainage for Breast Cancer-related Lymphedema: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin Breast Cancer 22 (5): e664-e673, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hayes SC, Singh B, Reul-Hirche H, et al.: The Effect of Exercise for the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer-Related Lymphedema: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 54 (8): 1389-1399, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel A, et al.: Weight lifting in women with breast-cancer-related lymphedema. N Engl J Med 361 (7): 664-73, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Singh B, Disipio T, Peake J, et al.: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Exercise for Those With Cancer-Related Lymphedema. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 97 (2): 302-315.e13, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Do JH, Kim W, Cho YK, et al.: EFFECTS OF RESISTANCE EXERCISES AND COMPLEX DECONGESTIVE THERAPY ON ARM FUNCTION AND MUSCULAR STRENGTH IN BREAST CANCER RELATED LYMPHEDEMA. Lymphology 48 (4): 184-96, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Campbell KL, Winters-Stone KM, Wiskemann J, et al.: Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors: Consensus Statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc 51 (11): 2375-2390, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rockson SG, Tian W, Jiang X, et al.: Pilot studies demonstrate the potential benefits of antiinflammatory therapy in human lymphedema. JCI Insight 3 (20): , 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schaverien MV, Coroneos CJ: Surgical Treatment of Lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 144 (3): 738-758, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Forte AJ, Boczar D, Huayllani MT, et al.: Pharmacotherapy Agents in Lymphedema Treatment: A Systematic Review. Cureus 11 (12): e6300, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Engel H, Lin CY, Huang JJ, et al.: Outcomes of Lymphedema Microsurgery for Breast Cancer-related Lymphedema With or Without Microvascular Breast Reconstruction. Ann Surg 268 (6): 1076-1083, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cha HG, Oh TM, Cho MJ, et al.: Changing the Paradigm: Lymphovenous Anastomosis in Advanced Stage Lower Extremity Lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 147 (1): 199-207, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gould DJ, Mehrara BJ, Neligan P, et al.: Lymph node transplantation for the treatment of lymphedema. J Surg Oncol 118 (5): 736-742, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Fish ML, Grover R, Schwarz GS: Quality-of-Life Outcomes in Surgical vs Nonsurgical Treatment of Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: A Systematic Review. JAMA Surg 155 (6): 513-519, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Aljaaly HA, Fries CA, Cheng MH: Dorsal Wrist Placement for Vascularized Submental Lymph Node Transfer Significantly Improves Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 7 (2): e2149, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gratzon A, Schultz J, Secrest K, et al.: Clinical and Psychosocial Outcomes of Vascularized Lymph Node Transfer for the Treatment of Upper Extremity Lymphedema After Breast Cancer Therapy. Ann Surg Oncol 24 (6): 1475-1481, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Chen WF, Zeng WF, Hawkes PJ, et al.: Lymphedema Liposuction with Immediate Limb Contouring. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 7 (11): e2513, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lee D, Piller N, Hoffner M, et al.: Liposuction of Postmastectomy Arm Lymphedema Decreases the Incidence of Erysipelas. Lymphology 49 (2): 85-92, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hoffner M, Ohlin K, Svensson B, et al.: Liposuction Gives Complete Reduction of Arm Lymphedema following Breast Cancer Treatment-A 5-year Prospective Study in 105 Patients without Recurrence. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 6 (8): e1912, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Baxter GD, Liu L, Petrich S, et al.: Low level laser therapy (Photobiomodulation therapy) for breast cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review. BMC Cancer 17 (1): 833, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Menzer C, Aleisa A, Wilson BN, et al.: Efficacy of laser CO2 treatment for refractory lymphedema secondary to cancer treatments. Lasers Surg Med 54 (3): 337-341, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

Disease-Specific Interventions for Prevention or Treatment of Lymphedema

Breast Cancer: Prevention of Lymphedema

Compression garments

A randomized study of women who underwent an axillary dissection suggested that compression sleeves worn from the first postoperative day until 3 months after completion of adjuvant therapy reduced the risk of lymphedema.[1][Level of evidence: I] Women (n = 155) who were randomly assigned to the compression intervention had less arm swelling, as determined by bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS) thresholds and relative arm volume increase (RAVI), than women assigned to usual care. The cumulative incidence of arm swelling at 1 year was 42% by BIS and 14% by RAVI in women who received compression garments, compared with 52% and 25%, respectively, for usual care. The hazard ratio for developing arm swelling in the compression group relative to the control group was 0.61 (95% confidence interval, 0.43–0.85; P = .004) by BIS and 0.56 (95% CI, 0.33–0.96; P = .034) by RAVI. There were no differences in patient-reported outcomes.

Exercise

A randomized trial suggested that exercise might help prevent lymphedema after breast cancer surgery.[2][Level of evidence: I] The investigators randomly assigned 77 eligible women to a control arm or to 12 months of gym membership with a 13-week training session in weightlifting. Eligibility criteria included a diagnosis of breast cancer within 1 to 5 years, at least two lymph nodes removed, a body mass index (BMI) of less than 50, no prior history of lymphedema, and no asymmetry in the arms greater than 10%. The primary outcome was an increase in affected arm volume of greater than 5% at 1 year. A secondary outcome was clinician-defined lymphedema. The percentages of women who met the criteria for the primary outcome in the control and weightlifting cohorts were 17% and 11%, respectively (P = .04). The reduction in the rate in women who had five or more lymph nodes removed was even greater (22% in the control cohort vs. 7% in the weightlifting cohort; P = .003). However, there were no differences in the rates of clinician-defined lymphedema, which were much lower in each arm (4.4% in the control cohort vs. 1.5% in the weightlifting cohort).

A 2021 randomized trial studied patients with breast cancer who underwent either an axillary or sentinel lymph node dissection.[3][Level of evidence: I] The investigators randomly assigned 568 women to one of two groups. All subjects met with a trained lymphedema prevention educator and received information about lymphedema, including preventive self-care practices. The 315 women receiving the active intervention met with a physical therapist who provided an individual exercise program, weights, and an elastic compression sleeve to wear. The primary end point was the lymphedema-free rate at 18 months. Lymphedema was defined by either an increase in volume of the affected extremity of more than 10% or a doctor’s diagnosis. There were no differences between groups in the primary end point. Overall, 69% of participants in the education-only arm and 70% in the intervention arm were free of lymphedema at 18 months. But adherence in the intervention arm was poor (less than 50%) due to time constraints and a perceived lack of benefit. There were no differences in health-related quality of life between the cohorts.[4]

At present, exercise therapy with compression garments may not effectively prevent lymphedema. Exercise with other interventions has been investigated. For example, one study reported the results of a randomized trial of manual lymphatic drainage in addition to exercise therapy in preventing lymphedema.[5][Level of evidence: I] The investigators randomly assigned 160 women to receive or not receive manual lymphatic drainage in addition to exercise and suggestions to minimize lymphedema. Participants underwent serial volume measurements. At 6 months, 24% of women in the intervention group and 19% in the control group had an increase in volume of greater than 200 mL.

Breast Cancer: Treatment of Lymphedema

Complete decongestive therapy (CDT)

Compression sleeves alone may prevent progression of less severe lymphedema, but women often need more intensive interventions.[6][Level of evidence: I] In one study, 103 women had post–breast cancer lymphedema that caused at least a 10% increase in volume in the affected arm compared with the unaffected arm. Participants were randomly assigned to either CDT comprising elastic compression garments plus 20 daily manual lymphatic drainage sessions with a trained therapist (n = 57) or elastic compression garments alone (n = 46).[7][Level of evidence: I] The primary outcome was the percentage change in excess arm volume from baseline to 6 weeks. The women assigned to CDT experienced greater absolute volume loss than the women treated with compression garments alone (250 mL vs. 143 mL). However, there were no differences in the mean reduction of excess arm volume between the groups due to baseline differences in arm volumes in the two cohorts. In addition, there were no differences in the secondary outcomes and arm function.

Physical exercise

The results of randomized trials of physical exercise compared with usual care do not consistently demonstrate a benefit for patients with breast cancer and lymphedema. One study showed that women who underwent wide excision and axillary dissection and were randomly assigned to a supervised exercise program (3 hours per week for 12 weeks) reported fewer lymphedema-related symptoms than women assigned to a control group.[8][Level of evidence: I] The exercise group demonstrated greater reduction in extracellular fluid, as assessed with bioimpedance spectroscopy, compared with the control group. There was no significant difference in dermal thickness of the breast, as assessed by ultrasound.

Based on promising results of a facility-based exercise intervention, one trial used a 2 x 2 factorial design to test a home-based exercise program, with or without a weight-loss intervention led by a dietitian.[9][Level of evidence: I] The investigators randomly assigned 351 eligible women into one of four groups: control (n = 90), exercise alone (n = 87), weight loss alone (n = 87), and combined exercise and weight loss (n = 87). All patients received compression garments and consultations with certified lymphedema therapists. Eligibility criteria included evidence of lymphedema by clinical exam or history of lymphedema more than 6 months after surgery, a BMI between 25 and 50, and the ability to exercise but no history of consistent exercising. The primary outcome was the percentage difference between affected and nonaffected limbs. Secondary outcomes included clinician evaluation, patient surveys, and rates of lymphedema exacerbation or cellulitis. There were no differences of note between the various groups in the outcomes. This result raises the possibility that home-based therapies are inferior to facility-based treatment. The role of weight loss, if any, remains to be further elucidated.

Lymph node transplantation

A randomized trial of microsurgical lymph node transplantation and compression-physiotherapy versus compression-physiotherapy alone was reported.[10][Level of evidence: I] The 18 patients who underwent surgery had a greater reduction in limb volume (57% vs. 18%), fewer infectious complications from the lymphedema, and improved symptoms and functional status, compared with patients who received only compression-physiotherapy. The authors estimated that the procedure was cost effective when accounting for the reduction in complications from lymphedema.

Cervical Cancer: Prevention of Lymphedema

One study enrolled 120 women with cervical cancer who underwent a laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy. Participants were randomly assigned to an education-alone intervention or a CDT intervention.[11][Level of evidence: I] The CDT consisted of training in manual lymphatic drainage, followed by self-administered manual lymphatic drainage at home, compression hosiery, and an aerobic exercise program. The interventions were initiated 7 to 10 days after surgery. Additional eligibility criteria included more than 20 lymph nodes removed or anticipated radiation therapy (both of which are risk factors for lower-extremity lymphedema after surgery for cervical cancer). The primary outcome was limb volume calculated from multiple circumference measurements. Secondary outcomes included patients' self-reported symptoms related to lymphedema. After a follow-up of 1 year, 20 of 58 patients (24%) in the control arm and 8 of 59 (14%) in the CDT arm developed lymphedema (P = .008). The excess volume was less in the experimental arm as well. However, there were no differences in patient-reported symptoms or severity grading of the lymphedema. These promising results were supported by a smaller pilot study[12] and a retrospective review of a single-institution experience with women who developed lymphedema after treatment of a variety of gynecological cancers.[13]

Head and Neck Cancer: Treatment of Lymphedema

Systematic review

A systematic review examined publications related to lymphedema treatment in patients who had been treated for head and neck cancers.[14] The authors identified 23 primary studies, including 14 cohort studies, 7 case reports, and 2 randomized controlled trials. The interventions included manual lymphatic drainage, acupuncture, selenium supplementation, and liposuction.

CDT

A small randomized trial in patients with lymphedema after surgery for head and neck cancer assigned 21 patients to one of three groups: control (n = 7), CDT (n = 7), and home-based therapy (n = 7).[15] The patients who received home-based therapy were taught manual lymphatic drainage techniques. The patients who received CDT wore a compression face mask and received manual lymphatic drainage from a trained therapist; the time commitment was significant. Patients in the CDT group experienced greater volume reduction and no fibrotic complications. The small sample size and the time commitment required to receive CDT suggested the effect should be verified in a larger study before wider adoption.

Advanced pneumatic compression device

The shortage of trained lymphedema therapists and the inconvenience of multiple clinic visits have encouraged the development of a device patients can use at home. In a small randomized trial of such a device, patients were assigned to the device (n = 24) or a wait-list control (n = 25).[16] At 8 weeks, subjects in the active treatment arm reported less distressing symptoms, and repeat endoscopic exams revealed less edema, compared with the control subjects. Assessments of function were not changed. The authors noted that patients tended to use the device once daily rather than the prescribed twice daily. Further study is required.

Liposuction

There is a small randomized trial of submental liposuction in patients who complained of swelling after treatment of head and neck cancer. The ten patients who underwent liposuction reported greater improvements in personal appearance, compared with control subjects, at 6 months. No adverse effects from liposuction were reported.[17][Level of evidence: I]

Sarcoma of the Extremity: Prevention of Lymphedema

One study compared the incidence of lymphedema in a cohort of eight patients with thigh sarcoma, who had lymphatico-venous anastomoses performed in combination with resection of thigh soft-tissue tumors, with a historical cohort of 20 patients.[18] Only one of eight patients experienced lymphedema, compared with nine patients in the historical cohort. Patient self-reported symptoms were uncommon in the eight patients.

References

- Paramanandam VS, Dylke E, Clark GM, et al.: Prophylactic Use of Compression Sleeves Reduces the Incidence of Arm Swelling in Women at High Risk of Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol 40 (18): 2004-2012, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel AB, et al.: Weight lifting for women at risk for breast cancer-related lymphedema: a randomized trial. JAMA 304 (24): 2699-705, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Paskett ED, Le-Rademacher J, Oliveri JM, et al.: A randomized study to prevent lymphedema in women treated for breast cancer: CALGB 70305 (Alliance). Cancer 127 (2): 291-299, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Naughton MJ, Liu H, Seisler DK, et al.: Health-related quality of life outcomes for the LEAP study-CALGB 70305 (Alliance): A lymphedema prevention intervention trial for newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. Cancer 127 (2): 300-309, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Devoogdt N, Geraerts I, Van Kampen M, et al.: Manual lymph drainage may not have a preventive effect on the development of breast cancer-related lymphoedema in the long term: a randomised trial. J Physiother 64 (4): 245-254, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Blom KY, Johansson KI, Nilsson-Wikmar LB, et al.: Early intervention with compression garments prevents progression in mild breast cancer-related arm lymphedema: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Oncol 61 (7): 897-905, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dayes IS, Whelan TJ, Julian JA, et al.: Randomized trial of decongestive lymphatic therapy for the treatment of lymphedema in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 31 (30): 3758-63, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kilbreath SL, Ward LC, Davis GM, et al.: Reduction of breast lymphoedema secondary to breast cancer: a randomised controlled exercise trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 184 (2): 459-467, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schmitz KH, Troxel AB, Dean LT, et al.: Effect of Home-Based Exercise and Weight Loss Programs on Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema Outcomes Among Overweight Breast Cancer Survivors: The WISER Survivor Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 5 (11): 1605-1613, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dionyssiou D, Demiri E, Tsimponis A, et al.: A randomized control study of treating secondary stage II breast cancer-related lymphoedema with free lymph node transfer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 156 (1): 73-9, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wang X, Ding Y, Cai HY, et al.: Effectiveness of modified complex decongestive physiotherapy for preventing lower extremity lymphedema after radical surgery for cervical cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Gynecol Cancer 30 (6): 757-763, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Shallwani SM, Towers A, Newman A, et al.: Feasibility of a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial Examining a Multidimensional Intervention in Women with Gynecological Cancer at Risk of Lymphedema. Curr Oncol 28 (1): 455-470, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Liao SF, Li SH, Huang HY: The efficacy of complex decongestive physiotherapy (CDP) and predictive factors of response to CDP in lower limb lymphedema (LLL) after pelvic cancer treatment. Gynecol Oncol 125 (3): 712-5, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tyker A, Franco J, Massa ST, et al.: Treatment for lymphedema following head and neck cancer therapy: A systematic review. Am J Otolaryngol 40 (5): 761-769, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ozdemir K, Keser I, Duzlu M, et al.: The Effects of Clinical and Home-based Physiotherapy Programs in Secondary Head and Neck Lymphedema. Laryngoscope 131 (5): E1550-E1557, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ridner SH, Dietrich MS, Deng J, et al.: Advanced pneumatic compression for treatment of lymphedema of the head and neck: a randomized wait-list controlled trial. Support Care Cancer 29 (2): 795-803, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Alamoudi U, Taylor B, MacKay C, et al.: Submental liposuction for the management of lymphedema following head and neck cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 47 (1): 22, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wagner JM, Dadras M, Ufton D, et al.: Prophylactic lymphaticovenous anastomoses for resection of soft tissue tumors of the thigh to prevent secondary lymphedema-a retrospective comparative cohort analysis. Microsurgery 42 (3): 239-245, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

Latest Updates to This Summary (12/18/2024)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

Added level of evidence I.

Added level of evidence II.

Added level of evidence II.

Added level of evidence II.

Added level of evidence II and level of evidence IV.

Prevention and Treatment Options Overview for Lymphedema

Added level of evidence I.

Added level of evidence I.

Added level of evidence IV.

Added level of evidence II and level of evidence III.

Disease-Specific Interventions for Prevention or Treatment of Lymphedema

Added level of evidence I.

Added level of evidence I.

Added level of evidence I.

Added level of evidence I.

Added level of evidence I.

Added level of evidence I.

Added level of evidence I.

Added level of evidence I.

Added level of evidence I.

Added level of evidence I.

This summary is written and maintained by the PDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of NCI. The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or NIH. More information about summary policies and the role of the PDQ Editorial Boards in maintaining the PDQ summaries can be found on the About This PDQ Summary and PDQ® Cancer Information for Health Professionals pages.

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the diagnosis and treatment of lymphedema. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewers for Lymphedema are:

- Larry D. Cripe, MD (Indiana University School of Medicine)

- James T. Pastrnak, MD (Indiana University School of Medicine)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's Email Us. Do not contact the individual Board Members with questions or comments about the summaries. Board members will not respond to individual inquiries.

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board uses a formal evidence ranking system in developing its level-of-evidence designations.

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as “NCI’s PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary].”

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board. PDQ Lymphedema. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/lymphedema/lymphedema-hp-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389244]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in Visuals Online, a collection of over 2,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

The information in these summaries should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website’s Email Us.