Childhood Craniopharyngioma Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version

General Information About Childhood Craniopharyngioma

Primary brain tumors, including craniopharyngiomas, are a diverse group of diseases that together constitute the most common solid tumors of childhood. Brain tumors are classified according to an integrated assessment of histology and molecular characteristics, with tumor location and extent of spread as important factors that affect treatment and prognosis.

Craniopharyngiomas are uncommon pediatric brain tumors. They are believed to be congenital in origin, arising from ectodermal remnants, Rathke cleft, or other embryonal epithelium. They often occur in the suprasellar region with an intrasellar portion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) imaging are used to diagnose craniopharyngiomas, but histological confirmation is generally required before treatment.

The treatment of patients with newly diagnosed craniopharyngiomas may include surgery, radiation therapy, cyst drainage, and intracystic therapies. The treatment of patients with recurrent craniopharyngiomas depends on the initial treatment used. With current treatment strategies, the 5-year and 10-year survival rates reach 80% to 90% for children between the ages of 0 and 14 years.[1]

The PDQ childhood brain tumor treatment summaries are organized primarily according to the World Health Organization Classification of Central Nervous System (CNS) Tumours.[2,3] For a full description of the classification of CNS tumors and a link to the corresponding treatment summary for each type of brain tumor, see Childhood Brain and Spinal Cord Tumors Summary Index.

Incidence

Craniopharyngiomas are relatively uncommon, accounting for about 3% of all intracranial tumors in children.[1,4,5]

No predisposing factors have been identified.

Anatomy

Clinical Presentation

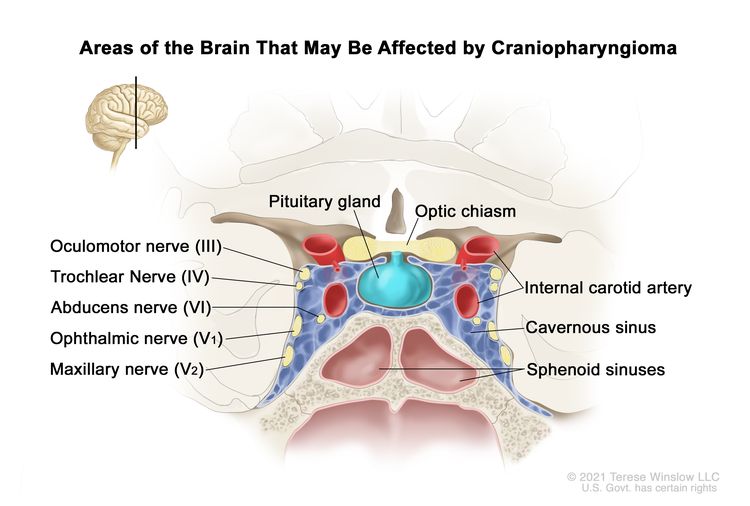

Craniopharyngiomas occur in the suprasellar region, near the pituitary gland, optic nerves, and optic chiasm (see Figure 2). This proximity commonly leads to injury of these surrounding structures, both by the tumor and interventions used to treat the tumor. Endocrine function is most frequently affected,[6-11] with patients suffering from neuroendocrine deficits such as growth hormone, thyroid, and cortisol deficiencies. Additionally, tumor proximity to the optic nerves and chiasm may result in visual compromise.[12][Level of evidence C1]; [7,13-15] Some patients present with obstructive hydrocephalus caused by tumor growth within the third ventricle. Rarely, tumors may extend into the posterior fossa, and patients may present with headache, diplopia, ataxia, and hearing loss.[16]

Diagnostic Evaluation

CT and MRI scans are often diagnostic for childhood craniopharyngiomas, with most tumors demonstrating intratumoral calcifications and a solid and cystic component. MRI of the spinal axis is not routinely performed.

Craniopharyngiomas without calcification may be confused with other tumor types, including germ cell tumors, hypothalamic/chiasmatic astrocytomas, or Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Biopsy or resection is required to confirm the diagnosis.[17]

Apart from imaging, patients undergo endocrine testing and formal vision examination, including visual-field evaluation.

Prognosis

Regardless of the treatment modality, the 5-year and 10-year overall survival rates range from 80% to 90% in children between the ages of 0 and 14 years.[1,18-21] The event-free survival (EFS) rates can be more variable, depending on therapy and clinical characteristics of the patient and tumor. EFS rates range from 23% for younger children to 65% for school-aged children.[22,23]

References

- Ostrom QT, Cioffi G, Waite K, et al.: CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2014-2018. Neuro Oncol 23 (12 Suppl 2): iii1-iii105, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, et al.: The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro Oncol 23 (8): 1231-1251, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, ed.: WHO Classification of Tumours: Central Nervous System Tumours. Vol. 6. 5th ed. IARC Press; 2021.

- Karavitaki N, Wass JA: Craniopharyngiomas. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 37 (1): 173-93, ix-x, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Garnett MR, Puget S, Grill J, et al.: Craniopharyngioma. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2: 18, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- van Schaik J, Hoving EW, Müller HL, et al.: Hypothalamic-Pituitary Outcome after Treatment for Childhood Craniopharyngioma. Front Horm Res 54: 47-57, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jimenez RB, Ahmed S, Johnson A, et al.: Proton Radiation Therapy for Pediatric Craniopharyngioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 110 (5): 1480-1487, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bogusz A, Müller HL: Childhood-onset craniopharyngioma: latest insights into pathology, diagnostics, treatment, and follow-up. Expert Rev Neurother 18 (10): 793-806, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tan TS, Patel L, Gopal-Kothandapani JS, et al.: The neuroendocrine sequelae of paediatric craniopharyngioma: a 40-year meta-data analysis of 185 cases from three UK centres. Eur J Endocrinol 176 (3): 359-369, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cohen M, Bartels U, Branson H, et al.: Trends in treatment and outcomes of pediatric craniopharyngioma, 1975-2011. Neuro Oncol 15 (6): 767-74, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Fouda MA, Scott RM, Marcus KJ, et al.: Sixty years single institutional experience with pediatric craniopharyngioma: between the past and the future. Childs Nerv Syst 36 (2): 291-296, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Nuijts MA, Veldhuis N, Stegeman I, et al.: Visual functions in children with craniopharyngioma at diagnosis: A systematic review. PLoS One 15 (10): e0240016, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wan MJ, Zapotocky M, Bouffet E, et al.: Long-term visual outcomes of craniopharyngioma in children. J Neurooncol 137 (3): 645-651, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ravindra VM, Okcu MF, Ruggieri L, et al.: Comparison of multimodal surgical and radiation treatment methods for pediatric craniopharyngioma: long-term analysis of progression-free survival and morbidity. J Neurosurg Pediatr 28 (2): 152-159, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Felicetti F, Brignardello E, van Santen HM, eds.: Endocrine and Metabolic Late Effects in Cancer Survivors. Basel, Switzerland: Karger, 2021.

- Zhou L, Luo L, Xu J, et al.: Craniopharyngiomas in the posterior fossa: a rare subgroup, diagnosis, management and outcomes. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 80 (10): 1150-4, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rossi A, Cama A, Consales A, et al.: Neuroimaging of pediatric craniopharyngiomas: a pictorial essay. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 19 (Suppl 1): 299-319, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Muller HL: Childhood craniopharyngioma. Recent advances in diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Horm Res 69 (4): 193-202, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Müller HL: Childhood craniopharyngioma--current concepts in diagnosis, therapy and follow-up. Nat Rev Endocrinol 6 (11): 609-18, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Zacharia BE, Bruce SS, Goldstein H, et al.: Incidence, treatment and survival of patients with craniopharyngioma in the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program. Neuro Oncol 14 (8): 1070-8, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ostrom QT, Cioffi G, Gittleman H, et al.: CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2012-2016. Neuro Oncol 21 (Suppl 5): v1-v100, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Beckhaus J, Friedrich C, Boekhoff S, et al.: Outcome after pediatric craniopharyngioma: the role of age at diagnosis and hypothalamic damage. Eur J Endocrinol 188 (3): , 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Merchant TE, Dangda S, Hoehn ME, et al.: Pediatric Craniopharyngioma: The Effect of Visual Deficits and Hormone Deficiencies on Long-Term Cognitive Outcomes After Conformal Photon Radiation Therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 115 (3): 581-591, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

Histopathological Classification of Childhood Craniopharyngioma

Craniopharyngiomas are histologically benign and often occur in the suprasellar region, with an intrasellar portion. They may be locally invasive and typically do not metastasize to remote brain locations.

Craniopharyngiomas are classified under the category of tumors of the sella region according to the defined entities below. The two entities were previously described as subtypes of craniopharyngioma. However, based on the different populations they tend to affect, combined with distinct clinical, histological, and molecular characteristics, these are now considered unique diagnoses.[1]

- Adamantinomatous: Adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas most frequently occur in children.[2] These tumors are typically composed of a solid portion formed by nests and trabeculae of epithelial tumor cells, with an abundance of calcification, and a cystic component that is filled with a dark, oily fluid. Wet keratin is also characteristic of this tumor type. Adamantinomatous craniopharyngiomas are more locally aggressive than are papillary craniopharyngiomas and have a significantly higher rate of recurrence.[3] Activating CTNNB1 gene variants are found in most adamantinomatous tumors.[1,4-6]

- Papillary: Papillary craniopharyngiomas occur primarily in adults. BRAF V600E variants are observed in nearly all papillary craniopharyngiomas.[1,5,6]

References

- Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, et al.: The 2021 WHO Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Neuro Oncol 23 (8): 1231-1251, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Karavitaki N, Wass JA: Craniopharyngiomas. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 37 (1): 173-93, ix-x, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Pekmezci M, Louie J, Gupta N, et al.: Clinicopathological characteristics of adamantinomatous and papillary craniopharyngiomas: University of California, San Francisco experience 1985-2005. Neurosurgery 67 (5): 1341-9; discussion 1349, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sekine S, Shibata T, Kokubu A, et al.: Craniopharyngiomas of adamantinomatous type harbor beta-catenin gene mutations. Am J Pathol 161 (6): 1997-2001, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Brastianos PK, Taylor-Weiner A, Manley PE, et al.: Exome sequencing identifies BRAF mutations in papillary craniopharyngiomas. Nat Genet 46 (2): 161-5, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Goschzik T, Gessi M, Dreschmann V, et al.: Genomic Alterations of Adamantinomatous and Papillary Craniopharyngioma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 76 (2): 126-134, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

Stage Information for Childhood Craniopharyngioma

There is no generally applied staging system for childhood craniopharyngiomas. For treatment purposes, patients are grouped as having newly diagnosed or recurrent disease.

Treatment Option Overview for Childhood Craniopharyngioma

Treatments for pediatric craniopharyngiomas have traditionally included maximal safe surgical resection and radiation therapy to treat residual tumor. Additionally, intracystic therapies such as radioactive phosphorus P 32, bleomycin, and interferon-alpha have been used. Evidence has demonstrated that conservative surgical approaches lead to better neuroendocrine and quality-of-life outcomes in patients.[1,2] Additionally, as the biological understanding of molecular and inflammatory drivers of these tumors have been identified, targeted therapies are now being studied.

Table 1 describes the treatment options for newly diagnosed and recurrent childhood craniopharyngioma.

| Treatment Group | Treatment Options |

|---|---|

| Newly diagnosed childhood craniopharyngioma | Complete resection with or without radiation therapy |

| Subtotal resection with radiation therapy | |

| Primary cyst drainage with or without radiation therapy | |

| Intracystic therapy | |

| Progressive or recurrent childhood craniopharyngioma | Surgery |

| Radiation therapy, including radiosurgery | |

| Intracystic therapy (intracavitary instillation of radioactive phosphorus P 32 or bleomycin for those with cystic recurrences, where these agents are available) | |

| Systemic and targeted therapy | |

| Observation |

References

- Lohkamp LN, Kasper EM, Pousa AE, et al.: An update on multimodal management of craniopharyngioma in children. Front Oncol 13: 1149428, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bogusz A, Müller HL: Childhood-onset craniopharyngioma: latest insights into pathology, diagnostics, treatment, and follow-up. Expert Rev Neurother 18 (10): 793-806, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Newly Diagnosed Childhood Craniopharyngioma

There is no consensus on the optimal treatment for patients with newly diagnosed craniopharyngioma, in part because of the lack of prospective randomized trials that compare the different treatment options. Treatment is individualized on the basis of the following factors:

- Tumor size.

- Tumor location.

- Extension of the tumor.

- Potential short-term and long-term toxicity, partially related to baseline neuroendocrine and vision deficits (i.e., more conservative surgical approaches may be prioritized in patients who do not have existing neuroendocrine or visual deficits to mitigate the risk of surgical morbidity).[1]

Established treatment options for newly diagnosed childhood craniopharyngioma include the following:

Complete Resection With or Without Radiation Therapy

It may be possible to remove all visible tumor and achieve long-term disease control.[2-4][Level of evidence C1] A 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate of about 65% has been reported.[5] Reported recurrence rates range from less than 10% to nearly 50%.[6,7] Gross-total resection is often technically challenging because the tumor is surrounded by vital structures, including the optic nerves and chiasm, the carotid artery and its branches, the pituitary and hypothalamus, and the third cranial nerve. These structures may limit the ability to remove the entire tumor. Conservative surgical approaches are often used to preserve functional and quality-of-life outcomes.[8,9][Level of evidence C1]

Many surgical approaches have been described, and the choice is determined by tumor size, location, extension, and the patient's baseline signs and symptoms of disease. Surgical approaches include the following:

- Craniotomy: As noted above, gross-total resection may be technically challenging because the tumor is surrounded by vital structures. The surgeon often has a limited view of the hypothalamic and sellar regions, and portions of the mass may remain after surgery, accounting for some recurrences. An understanding of the complex variations in how the tumors grow anatomically may help facilitate gross-total resection.[10] Nonetheless, almost all craniopharyngiomas attach to the pituitary stalk. Of the patients who undergo complete resection, virtually all will require lifelong pituitary hormone replacement with multiple medications.[3,11]

- Transsphenoidal approach: A transsphenoidal approach has been proven possible in patients of all ages and for tumors of various sizes localized within the sella.[12]; [13][Level of evidence C1] The development of expanded endonasal techniques with endoscopic visualization has allowed increased use of this approach, even for sizeable childhood tumors, which is similar to the experience in adults.[14] A complete resection can be obtained using this approach, with associated complications of panhypopituitarism and the risk of cerebrospinal fluid leaks.[15,16] When an endonasal approach is not possible, a craniotomy is required.

Complications of complete resection using either approach include the following:

If the surgeon indicates that the tumor was not completely removed or if postoperative imaging reveals residual craniopharyngioma, radiation therapy may be recommended to prevent early progression.[19][Level of evidence C2] For more information, see the Subtotal Resection With Radiation Therapy section.

Routine surveillance using magnetic resonance imaging is performed for several years after complete resection because of the possibility of tumor recurrence.

Subtotal Resection With Radiation Therapy

The goal of limited surgery can be to establish a diagnosis, drain cystic components of the tumor, and decompress surrounding anatomical structures. In subtotal resections, removal of the tumor from the pituitary stalk or hypothalamus is typically avoided to minimize the late effects associated with complete resection.[20]

Surgery is often followed by radiation therapy, because radiation therapy can decrease the risk of recurrence after a subtotal resection.[21] With this approach, the 5-year PFS rates are approximately 70% to 90%,[5,22-25]; [26][Level of evidence C1] and the 10-year overall survival (OS) rates exceed 90%, which are similar to the rates in patients who undergo a gross-total resection.[27,28][Level of evidence C1]; [29][Level of evidence C2] Most often, radiation therapy is timed to immediately follow subtotal resection. However, in certain cases, such as in young patients or in patients without existing neuroendocrine or visual deficits, serial imaging may be used to delay or avoid radiation therapy for as long as feasible.[7,30] The standard approach to radiation therapy involves fractionated external-beam radiation, with a recommended dose of 50 to 54 Gy, in 1.8-Gy fractions, restricting the optic chiasm dose to 54 Gy.[31-34] Newer radiation technologies such as intensity-modulated photon therapy and proton-beam radiation therapy may reduce the radiation dose to uninvolved parts of the brain and spare normal tissue.[23,34-36] It is unknown whether such techniques reduce the late effects of radiation therapy.[26,34,36,37] Transient cyst enlargement may be noted during radiation therapy, and serial imaging may be required during radiation therapy to assess cyst changes and consider updates to radiation mapping.[38][Level of evidence C3]

Surgical complications with a subtotal resection can be similar to, but are less likely than, with a complete resection. If radiation therapy is used, additional complications must be considered, including the following:

A phase II single-arm study included 94 patients (aged 12 months to 21 years) with craniopharyngiomas who were treated with proton-beam radiation therapy after individualized surgical resection. These patients were compared with a historical cohort of patients who were treated with photon-beam radiation therapy.[41] The survival outcomes of patients who received proton therapy were similar to those of patients who received photon therapy. The cumulative incidence rates of necrosis, vasculopathy, changes in vision, and severe complications were also similar between the two groups of patients. However, patients treated with proton therapy in the more recent cohort had superior cognitive outcomes.

A long-term study of 101 children who were treated for craniopharyngiomas evaluated visual, neurocognitive, and endocrine outcomes after photon radiation therapy. Race and presence of a shunt affected baseline scores.[42] For children who presented with lower intelligence quotient (IQ) scores at diagnosis, the impact of treatment often resulted in an IQ score reduction to the borderline mental disability range of 70 to 84. The investigators demonstrated that age at treatment (younger children had worse outcomes), radiation dose to the temporal lobes and hippocampi, and visual impairment significantly impacted neurocognitive function after radiation therapy. This study demonstrates the importance of these factors in the treatment and late effects of craniopharyngioma.

A report from the prospective registry study KiProReg examined the use of proton-beam therapy in 84 children younger than 18 years with craniopharyngioma.[43] The estimated 3-year OS rate was 98.2%, and the PFS rate was 94.7%. With a median follow-up of 4.3 years, late toxicities appeared acceptable. Sixty-three of the patients were treated with pencil-beam scanning, which is considered an advancement in proton technology.

Primary Cyst Drainage With or Without Radiation Therapy

For predominantly cystic craniopharyngiomas, stereotactic drainage of the cyst, insertion of a catheter from which drainage can be facilitated, or cyst fenestration are other therapeutic alternatives.[7,44] This can be followed by observation or radiation therapy, depending on clinical and tumor characteristics . This procedure may also allow the surgeon to use the following two-staged approach:[45]

- Draining the cyst to relieve pressure and complicating symptoms.

- Resecting the tumor or employing radiation therapy later.

Intracystic Therapy

Intracystic therapies include peginterferon alpha, radioactive phosphorus P 32 (32P) or other compounds,[46-48]; [49][Level of evidence B4] and interferon-alpha (which is no longer commercially available).[50]; [51][Level of evidence C1]; [52][Level of evidence C2] Bleomycin has previously been used.[53]; [54][Level of evidence C2]

A systematic review of publications on the treatment of cystic craniopharyngiomas with radioisotope brachytherapy from 2010 to 2021 identified 66 pediatric patients (N = 228).[55] With a minimum follow-up of 5 years, partial and complete responses were achieved in 89% of children with purely cystic lesions, compared with 58% of children with nonexclusively cystic lesions. Visual improvement was achieved in 64% of the patients with purely cystic lesions, and endocrine improvement was achieved in 20% of these patients. The observed progression rate was 3% for patients with purely cystic lesions. Treatment with intracystic brachytherapy, most commonly using 32P and yttrium Y 90, can be considered for patients with purely cystic craniopharyngiomas.

Treatment Options Under Clinical Evaluation

Information about NCI-supported clinical trials can be found on the NCI website. For information about clinical trials sponsored by other organizations, see the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

Preclinical contemporary evaluations have identified active molecular and immune pathways in craniopharyngioma that may be targetable using commercially available or investigational agents. Specifically, MAPK and RAF pathways and immune/inflammatory targets such as PD-1 pathway components and IL-6 have been identified.[7,56-61][Level of evidence C1]

The following is an example of a national and/or institutional clinical trial that is currently being conducted:

- NCT05465174 (Nivolumab and Tovorafenib [DAY101] for Treatment of Craniopharyngioma in Children and Young Adults): This study assesses the tolerability and efficacy of combination therapy with PD-1 (nivolumab) and pan-RAF kinase (tovorafenib) inhibition for the treatment of children and young adults with craniopharyngioma.

References

- Cohen M, Bartels U, Branson H, et al.: Trends in treatment and outcomes of pediatric craniopharyngioma, 1975-2011. Neuro Oncol 15 (6): 767-74, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mortini P, Losa M, Pozzobon G, et al.: Neurosurgical treatment of craniopharyngioma in adults and children: early and long-term results in a large case series. J Neurosurg 114 (5): 1350-9, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Elliott RE, Hsieh K, Hochm T, et al.: Efficacy and safety of radical resection of primary and recurrent craniopharyngiomas in 86 children. J Neurosurg Pediatr 5 (1): 30-48, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Zhang YQ, Ma ZY, Wu ZB, et al.: Radical resection of 202 pediatric craniopharyngiomas with special reference to the surgical approaches and hypothalamic protection. Pediatr Neurosurg 44 (6): 435-43, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Yang I, Sughrue ME, Rutkowski MJ, et al.: Craniopharyngioma: a comparison of tumor control with various treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus 28 (4): E5, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Müller HL, Merchant TE, Puget S, et al.: New outlook on the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of childhood-onset craniopharyngioma. Nat Rev Endocrinol 13 (5): 299-312, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Apps JR, Muller HL, Hankinson TC, et al.: Contemporary Biological Insights and Clinical Management of Craniopharyngioma. Endocr Rev 44 (3): 518-538, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lohkamp LN, Kasper EM, Pousa AE, et al.: An update on multimodal management of craniopharyngioma in children. Front Oncol 13: 1149428, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bogusz A, Müller HL: Childhood-onset craniopharyngioma: latest insights into pathology, diagnostics, treatment, and follow-up. Expert Rev Neurother 18 (10): 793-806, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Morisako H, Goto T, Goto H, et al.: Aggressive surgery based on an anatomical subclassification of craniopharyngiomas. Neurosurg Focus 41 (6): E10, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sands SA, Milner JS, Goldberg J, et al.: Quality of life and behavioral follow-up study of pediatric survivors of craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg 103 (4 Suppl): 302-11, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bakhsheshian J, Jin DL, Chang KE, et al.: Risk factors associated with the surgical management of craniopharyngiomas in pediatric patients: analysis of 1961 patients from a national registry database. Neurosurg Focus 41 (6): E8, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Locatelli D, Massimi L, Rigante M, et al.: Endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal surgery for sellar tumors in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 74 (11): 1298-302, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Chivukula S, Koutourousiou M, Snyderman CH, et al.: Endoscopic endonasal skull base surgery in the pediatric population. J Neurosurg Pediatr 11 (3): 227-41, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mazzatenta D, Zoli M, Guaraldi F, et al.: Outcome of Endoscopic Endonasal Surgery in Pediatric Craniopharyngiomas. World Neurosurg 134: e277-e288, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lee JA, Cooper RL, Nguyen SA, et al.: Endonasal Endoscopic Surgery for Pediatric Sellar and Suprasellar Lesions: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 163 (2): 284-292, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Müller HL, Gebhardt U, Teske C, et al.: Post-operative hypothalamic lesions and obesity in childhood craniopharyngioma: results of the multinational prospective trial KRANIOPHARYNGEOM 2000 after 3-year follow-up. Eur J Endocrinol 165 (1): 17-24, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Clark AJ, Cage TA, Aranda D, et al.: Treatment-related morbidity and the management of pediatric craniopharyngioma: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Pediatr 10 (4): 293-301, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lin LL, El Naqa I, Leonard JR, et al.: Long-term outcome in children treated for craniopharyngioma with and without radiotherapy. J Neurosurg Pediatr 1 (2): 126-30, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Elowe-Gruau E, Beltrand J, Brauner R, et al.: Childhood craniopharyngioma: hypothalamus-sparing surgery decreases the risk of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98 (6): 2376-82, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Müller HL: Childhood craniopharyngioma: current controversies on management in diagnostics, treatment and follow-up. Expert Rev Neurother 10 (4): 515-24, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Winkfield KM, Tsai HK, Yao X, et al.: Long-term clinical outcomes following treatment of childhood craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 56 (7): 1120-6, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jimenez RB, Ahmed S, Johnson A, et al.: Proton Radiation Therapy for Pediatric Craniopharyngioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 110 (5): 1480-1487, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Eveslage M, Calaminus G, Warmuth-Metz M, et al.: The Postopera tive Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with Craniopharyngioma. Dtsch Arztebl Int 116 (18): 321-328, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Merchant TE, Hua CH, Shukla H, et al.: Proton versus photon radiotherapy for common pediatric brain tumors: comparison of models of dose characteristics and their relationship to cognitive function. Pediatr Blood Cancer 51 (1): 110-7, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Merchant TE, Kun LE, Hua CH, et al.: Disease control after reduced volume conformal and intensity modulated radiation therapy for childhood craniopharyngioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 85 (4): e187-92, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schoenfeld A, Pekmezci M, Barnes MJ, et al.: The superiority of conservative resection and adjuvant radiation for craniopharyngiomas. J Neurooncol 108 (1): 133-9, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Edmonston DY, Wu S, Li Y, et al.: Limited surgery and conformal photon radiation therapy for pediatric craniopharyngioma: long-term results from the RT1 protocol. Neuro Oncol 24 (12): 2200-2209, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Clark AJ, Cage TA, Aranda D, et al.: A systematic review of the results of surgery and radiotherapy on tumor control for pediatric craniopharyngioma. Childs Nerv Syst 29 (2): 231-8, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Beckhaus J, Friedrich C, Boekhoff S, et al.: Outcome after pediatric craniopharyngioma: the role of age at diagnosis and hypothalamic damage. Eur J Endocrinol 188 (3): , 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kiehna EN, Merchant TE: Radiation therapy for pediatric craniopharyngioma. Neurosurg Focus 28 (4): E10, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Harrabi SB, Adeberg S, Welzel T, et al.: Long term results after fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy (FSRT) in patients with craniopharyngioma: maximal tumor control with minimal side effects. Radiat Oncol 9: 203, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lo AC, Howard AF, Nichol A, et al.: Long-term outcomes and complications in patients with craniopharyngioma: the British Columbia Cancer Agency experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 88 (5): 1011-8, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bishop AJ, Greenfield B, Mahajan A, et al.: Proton beam therapy versus conformal photon radiation therapy for childhood craniopharyngioma: multi-institutional analysis of outcomes, cyst dynamics, and toxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 90 (2): 354-61, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Winkfield KM, Linsenmeier C, Yock TI, et al.: Surveillance of craniopharyngioma cyst growth in children treated with proton radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 73 (3): 716-21, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Beltran C, Roca M, Merchant TE: On the benefits and risks of proton therapy in pediatric craniopharyngioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 82 (2): e281-7, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Boehling NS, Grosshans DR, Bluett JB, et al.: Dosimetric comparison of three-dimensional conformal proton radiotherapy, intensity-modulated proton therapy, and intensity-modulated radiotherapy for treatment of pediatric craniopharyngiomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 82 (2): 643-52, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Shi Z, Esiashvili N, Janss AJ, et al.: Transient enlargement of craniopharyngioma after radiation therapy: pattern of magnetic resonance imaging response following radiation. J Neurooncol 109 (2): 349-55, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ishida M, Hotta M, Tsukamura A, et al.: Malignant transformation in craniopharyngioma after radiation therapy: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Neuropathol 29 (1): 2-8, 2010 Jan-Feb. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Aquilina K, Merchant TE, Rodriguez-Galindo C, et al.: Malignant transformation of irradiated craniopharyngioma in children: report of 2 cases. J Neurosurg Pediatr 5 (2): 155-61, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Merchant TE, Hoehn ME, Khan RB, et al.: Proton therapy and limited surgery for paediatric and adolescent patients with craniopharyngioma (RT2CR): a single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 24 (5): 523-534, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Merchant TE, Dangda S, Hoehn ME, et al.: Pediatric Craniopharyngioma: The Effect of Visual Deficits and Hormone Deficiencies on Long-Term Cognitive Outcomes After Conformal Photon Radiation Therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 115 (3): 581-591, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bischoff M, Khalil DA, Frisch S, et al.: Outcome After Modern Proton Beam Therapy in Childhood Craniopharyngioma: Results of the Prospective Registry Study KiProReg. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 120 (1): 137-148, 2024. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cinalli G, Spennato P, Cianciulli E, et al.: The role of transventricular neuroendoscopy in the management of craniopharyngiomas: three patient reports and review of the literature. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 19 (Suppl 1): 341-54, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schubert T, Trippel M, Tacke U, et al.: Neurosurgical treatment strategies in childhood craniopharyngiomas: is less more? Childs Nerv Syst 25 (11): 1419-27, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Julow J, Backlund EO, Lányi F, et al.: Long-term results and late complications after intracavitary yttrium-90 colloid irradiation of recurrent cystic craniopharyngiomas. Neurosurgery 61 (2): 288-95; discussion 295-6, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Barriger RB, Chang A, Lo SS, et al.: Phosphorus-32 therapy for cystic craniopharyngiomas. Radiother Oncol 98 (2): 207-12, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Maarouf M, El Majdoub F, Fuetsch M, et al.: Stereotactic intracavitary brachytherapy with P-32 for cystic craniopharyngiomas in children. Strahlenther Onkol 192 (3): 157-65, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kickingereder P, Maarouf M, El Majdoub F, et al.: Intracavitary brachytherapy using stereotactically applied phosphorus-32 colloid for treatment of cystic craniopharyngiomas in 53 patients. J Neurooncol 109 (2): 365-74, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ierardi DF, Fernandes MJ, Silva IR, et al.: Apoptosis in alpha interferon (IFN-alpha) intratumoral chemotherapy for cystic craniopharyngiomas. Childs Nerv Syst 23 (9): 1041-6, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cavalheiro S, Di Rocco C, Valenzuela S, et al.: Craniopharyngiomas: intratumoral chemotherapy with interferon-alpha: a multicenter preliminary study with 60 cases. Neurosurg Focus 28 (4): E12, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kilday JP, Caldarelli M, Massimi L, et al.: Intracystic interferon-alpha in pediatric craniopharyngioma patients: an international multicenter assessment on behalf of SIOPE and ISPN. Neuro Oncol 19 (10): 1398-1407, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Linnert M, Gehl J: Bleomycin treatment of brain tumors: an evaluation. Anticancer Drugs 20 (3): 157-64, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hukin J, Steinbok P, Lafay-Cousin L, et al.: Intracystic bleomycin therapy for craniopharyngioma in children: the Canadian experience. Cancer 109 (10): 2124-31, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Guimarães MM, Cardeal DD, Teixeira MJ, et al.: Brachytherapy in paediatric craniopharyngiomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis of recent literature. Childs Nerv Syst 38 (2): 253-262, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Petralia F, Tignor N, Reva B, et al.: Integrated Proteogenomic Characterization across Major Histological Types of Pediatric Brain Cancer. Cell 183 (7): 1962-1985.e31, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Apps JR, Carreno G, Gonzalez-Meljem JM, et al.: Tumour compartment transcriptomics demonstrates the activation of inflammatory and odontogenic programmes in human adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma and identifies the MAPK/ERK pathway as a novel therapeutic target. Acta Neuropathol 135 (5): 757-777, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hengartner AC, Prince E, Vijmasi T, et al.: Adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma: moving toward targeted therapies. Neurosurg Focus 48 (1): E7, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Coy S, Rashid R, Lin JR, et al.: Multiplexed immunofluorescence reveals potential PD-1/PD-L1 pathway vulnerabilities in craniopharyngioma. Neuro Oncol 20 (8): 1101-1112, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Grob S, Mirsky DM, Donson AM, et al.: Targeting IL-6 Is a Potential Treatment for Primary Cystic Craniopharyngioma. Front Oncol 9: 791, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Donson AM, Apps J, Griesinger AM, et al.: Molecular Analyses Reveal Inflammatory Mediators in the Solid Component and Cyst Fluid of Human Adamantinomatous Craniopharyngioma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 76 (9): 779-788, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Progressive or Recurrent Childhood Craniopharyngioma

Progression or recurrence of craniopharyngioma varies according to the type of up-front therapy, but it has been reported to be between 20% (patients who received a subtotal resection and radiation therapy) and 90% (patients who received a subtotal resection without radiation therapy).[1-3]

Treatment options for recurrent childhood craniopharyngioma include the following:

Surgery

The management of recurrent craniopharyngioma is determined largely by previous therapy. Repeat attempts at gross-total resections are difficult, and long-term disease control is achieved less often.[4][Level of evidence C2]; [3] Complications are more frequent than with initial surgery.[5][Level of evidence C2]

Radiation Therapy

If not previously employed, external-beam radiation therapy remains an option, including the consideration of radiosurgery in selected circumstances.[6][Level of evidence C2] Repeat irradiation in different forms is also an option when considering prior radiation exposures and toxicities. Reirradiation has been shown to be feasible in regaining tumor control and providing symptom relief.[7][Level of evidence C3] The types of radiation therapy can range from standard conformal radiation approaches to Gamma Knife therapy.[8][Level of evidence C3]

Intracystic Therapy

Cystic recurrences may be treated with intracavitary instillation of varying agents via placement of an Ommaya catheter.[9] These agents have included radioactive 32P or other compounds,[10-12]; [13][Level of evidence B4] bleomycin,[14]; [15][Level of evidence C2] or, previously, interferon-alpha (which is no longer commercially available).[16]; [17][Level of evidence C1]; [18][Level of evidence C2] These strategies have been useful in certain cases, and a low risk of complications has been reported. However, none of these approaches has shown efficacy against solid portions of the tumor.

Systemic and Targeted Therapy

Although systemic therapy is generally not used, a small series has shown that the use of subcutaneous peginterferon alpha-2b to manage cystic recurrences can result in durable responses; however, this agent is no longer commercially available.[19][Level of evidence C2]

Observation

In select cases of asymptomatic patients with minimal (<25%) tumor progression, it may be possible to safely observe these patients. Intervention can begin when new symptoms develop or further tumor growth is identified on subsequent imaging.[20]

Treatment Options Under Clinical Evaluation

Information about NCI-supported clinical trials can be found on the NCI website. For information about clinical trials sponsored by other organizations, see the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

Preclinical contemporary evaluations have identified active molecular and immune pathways in craniopharyngioma that may be targetable using commercially available or investigational agents. Specifically, MAPK and RAF pathways and immune/inflammatory targets such as PD-1 pathway components and IL-6 have been identified.[21-27][Level of evidence C1]

The following are examples of national and/or institutional clinical trials that are currently being conducted:

- NCT05465174 (Nivolumab and Tovorafenib [DAY101] for Treatment of Craniopharyngioma in Children and Young Adults): This study assesses the tolerability and efficacy of combination therapy with PD-1 (nivolumab) and pan-RAF kinase (tovorafenib) inhibition for the treatment of children and young adults with craniopharyngioma.

- NCT05286788 (Binimetinib [Mektovi] for the Treatment of Pediatric Adamantinomatous Craniopharyngioma): This phase II study will treat pediatric patients diagnosed with recurrent adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma with binimetinib (mektovi).

- NCT05233397 (Tocilizumab [Actemra] for the Treatment of Progressive or Recurrent Pediatric Adamantinomatous Craniopharyngioma): This phase II study will treat pediatric patients diagnosed with recurrent adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma with tocilizumab (actemra).

References

- Yang I, Sughrue ME, Rutkowski MJ, et al.: Craniopharyngioma: a comparison of tumor control with various treatment strategies. Neurosurg Focus 28 (4): E5, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bogusz A, Müller HL: Childhood-onset craniopharyngioma: latest insights into pathology, diagnostics, treatment, and follow-up. Expert Rev Neurother 18 (10): 793-806, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Liubinas SV, Munshey AS, Kaye AH: Management of recurrent craniopharyngioma. J Clin Neurosci 18 (4): 451-7, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Vinchon M, Dhellemmes P: Craniopharyngiomas in children: recurrence, reoperation and outcome. Childs Nerv Syst 24 (2): 211-7, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jang WY, Lee KS, Son BC, et al.: Repeat operations in pediatric patients with recurrent craniopharyngiomas. Pediatr Neurosurg 45 (6): 451-5, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Xu Z, Yen CP, Schlesinger D, et al.: Outcomes of Gamma Knife surgery for craniopharyngiomas. J Neurooncol 104 (1): 305-13, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Foran SJ, Laperriere N, Edelstein K, et al.: Reirradiation for recurrent craniopharyngioma. Adv Radiat Oncol 5 (6): 1305-1310, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kobayashi T: Long-term results of gamma knife radiosurgery for 100 consecutive cases of craniopharyngioma and a treatment strategy. Prog Neurol Surg 22: 63-76, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Steinbok P, Hukin J: Intracystic treatments for craniopharyngioma. Neurosurg Focus 28 (4): E13, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Julow J, Backlund EO, Lányi F, et al.: Long-term results and late complications after intracavitary yttrium-90 colloid irradiation of recurrent cystic craniopharyngiomas. Neurosurgery 61 (2): 288-95; discussion 295-6, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Barriger RB, Chang A, Lo SS, et al.: Phosphorus-32 therapy for cystic craniopharyngiomas. Radiother Oncol 98 (2): 207-12, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Maarouf M, El Majdoub F, Fuetsch M, et al.: Stereotactic intracavitary brachytherapy with P-32 for cystic craniopharyngiomas in children. Strahlenther Onkol 192 (3): 157-65, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kickingereder P, Maarouf M, El Majdoub F, et al.: Intracavitary brachytherapy using stereotactically applied phosphorus-32 colloid for treatment of cystic craniopharyngiomas in 53 patients. J Neurooncol 109 (2): 365-74, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Linnert M, Gehl J: Bleomycin treatment of brain tumors: an evaluation. Anticancer Drugs 20 (3): 157-64, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hukin J, Steinbok P, Lafay-Cousin L, et al.: Intracystic bleomycin therapy for craniopharyngioma in children: the Canadian experience. Cancer 109 (10): 2124-31, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ierardi DF, Fernandes MJ, Silva IR, et al.: Apoptosis in alpha interferon (IFN-alpha) intratumoral chemotherapy for cystic craniopharyngiomas. Childs Nerv Syst 23 (9): 1041-6, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cavalheiro S, Di Rocco C, Valenzuela S, et al.: Craniopharyngiomas: intratumoral chemotherapy with interferon-alpha: a multicenter preliminary study with 60 cases. Neurosurg Focus 28 (4): E12, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kilday JP, Caldarelli M, Massimi L, et al.: Intracystic interferon-alpha in pediatric craniopharyngioma patients: an international multicenter assessment on behalf of SIOPE and ISPN. Neuro Oncol 19 (10): 1398-1407, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Yeung JT, Pollack IF, Panigrahy A, et al.: Pegylated interferon-α-2b for children with recurrent craniopharyngioma. J Neurosurg Pediatr 10 (6): 498-503, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Fouda MA, Karsten M, Staffa SJ, et al.: Management strategies for recurrent pediatric craniopharyngioma: new recommendations. J Neurosurg Pediatr 27 (5): 548-555, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Petralia F, Tignor N, Reva B, et al.: Integrated Proteogenomic Characterization across Major Histological Types of Pediatric Brain Cancer. Cell 183 (7): 1962-1985.e31, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Apps JR, Muller HL, Hankinson TC, et al.: Contemporary Biological Insights and Clinical Management of Craniopharyngioma. Endocr Rev 44 (3): 518-538, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Apps JR, Carreno G, Gonzalez-Meljem JM, et al.: Tumour compartment transcriptomics demonstrates the activation of inflammatory and odontogenic programmes in human adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma and identifies the MAPK/ERK pathway as a novel therapeutic target. Acta Neuropathol 135 (5): 757-777, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hengartner AC, Prince E, Vijmasi T, et al.: Adamantinomatous craniopharyngioma: moving toward targeted therapies. Neurosurg Focus 48 (1): E7, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Coy S, Rashid R, Lin JR, et al.: Multiplexed immunofluorescence reveals potential PD-1/PD-L1 pathway vulnerabilities in craniopharyngioma. Neuro Oncol 20 (8): 1101-1112, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Grob S, Mirsky DM, Donson AM, et al.: Targeting IL-6 Is a Potential Treatment for Primary Cystic Craniopharyngioma. Front Oncol 9: 791, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Donson AM, Apps J, Griesinger AM, et al.: Molecular Analyses Reveal Inflammatory Mediators in the Solid Component and Cyst Fluid of Human Adamantinomatous Craniopharyngioma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 76 (9): 779-788, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

Late Effects in Patients Treated for Childhood Craniopharyngioma

Quality-of-life issues are important to pediatric patients with craniopharyngiomas and are difficult to generalize because of the various treatment modalities. In one series of 261 patients diagnosed with craniopharyngiomas before 2000, hypothalamic involvement was associated with lower overall survival (OS), impaired quality of life, and severe obesity.[1][Level of evidence C1] Other studies investigating quality of life in large, multi-institutional cohorts have correlated worse quality-of-life outcomes with variables such as older age at diagnosis, hypothalamic involvement, degree of postoperative hypothalamic injury, and degree of tumor resection.[2,3] Regardless of therapy, most patients with craniopharyngiomas experience long-term effects from the tumor and associated therapies.[2-6][Level of evidence B3]

Late effects of treatment for childhood craniopharyngioma include the following:

- Behavioral issues and memory deficits. Although intelligence quotient is usually maintained, behavioral issues and other cognitive domains such as memory, executive function, and attention are commonly impacted.[4,6-8] Memory and neurocognitive effects may be mitigated by the use of proton radiation therapy and conformal plans to avoid surrounding normal brain anatomy such as the hypothalamus and hippocampus.[9]; [10][Level of evidence B3]

- Visual disturbances. Visual disturbances, including visual field and acuity defects, have been reported. These deficits may be decreased with less aggressive surgical approaches or radiation therapy alone.[11][Level of evidence C1]; [6,10]

- Endocrine abnormalities. Endocrine abnormalities result in the almost universal need for lifelong endocrine replacement with multiple pituitary hormones.[5,8]; [12-14][Level of evidence C1] Similar to visual disturbances, endocrine injury can be offset by limited surgical resection [5,6,15-17] and intracystic therapies that minimize invasive interventions.[18]

- Decreased height. Growth hormone replacement therapy is used to improve growth in children treated for craniopharyngiomas. Growth hormone replacement initiated in childhood results in increases in height without impact on OS and progression-free survival when compared with children who did not receive growth hormone.[19][Level of evidence C1]; [20] Growth hormone administration beginning 1 year after diagnosis may be associated with early improvements in quality of life when measured at 3 years postdiagnosis.[21][Level of evidence C1] Published consensus guidelines do not support an increased risk of recurrence with use of growth hormones. They recommend considering growth hormone replacement therapy as early as 3 months after completing cancer therapy in patients who have stable disease and significant growth deficits.[22][Level of evidence D]

- Obesity. Obesity, which can be life-threatening, and the development of metabolic syndrome, including nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, can occur.[23,24] Children who undergo complete resection or subtotal resection may develop obesity, suggesting that a predilection to obesity may be a component of the disease itself, not the result of direct hypothalamic injury.[25][Level of evidence C1] Severe obesity seen in patients with craniopharyngiomas is more likely a result of a combination of factors such as tumor location and treatment characteristics, with multifaceted downstream impacts.[26][Level of evidence C1] In a study of 709 patients with craniopharyngiomas, posterior hypothalamic involvement or operative injury to the posterior hypothalamus appeared to be a key factor in the development of severe obesity.[3]

- Vasculopathies and stroke. Vasculopathies and subsequent strokes may result from local irradiation.[27,28] Previous studies have suggested that long-term growth hormone replacement may reduce the risk of stroke. Studies have also shown that pretreatment characteristics such as existing vascular injury, vessel location in the surgical field, and larger radiation doses to vascular structures increase the risk of long-term vessel stenosis.[28]; [29][Level of evidence C1] In a study of 94 pediatric patients with craniopharyngiomas who were treated with surgery and 54 Gy of proton therapy, the strongest predictor of postradiation therapy vasculopathy was preexisting vasculopathy.[29] The impact of proton radiation therapy was negligible within the operative corridor. Despite the high incidence (n = 27, 28.7%) of imaging-only evidence of subclinical stenosis events, only five patients required a revascularization procedure. In one of these patients, high-grade stenosis was present before radiation therapy. Two patients had previous tumor recurrences that required multiple resections before radiation therapy.

- Subsequent neoplasms. Subsequent neoplasms may result from local irradiation.[27] Secondary malignancies related to radiation therapy that specifically involve the pituitary/sellar region can range from malignant tumors, such as high-grade gliomas, to meningiomas. This risk is increased in patients who are younger at the time of radiation therapy.[30]

For information about the incidence, type, and monitoring of late effects in childhood and adolescent cancer survivors, see Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer.

References

- Sterkenburg AS, Hoffmann A, Gebhardt U, et al.: Survival, hypothalamic obesity, and neuropsychological/psychosocial status after childhood-onset craniopharyngioma: newly reported long-term outcomes. Neuro Oncol 17 (7): 1029-38, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Eveslage M, Calaminus G, Warmuth-Metz M, et al.: The Postopera tive Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents with Craniopharyngioma. Dtsch Arztebl Int 116 (18): 321-328, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Beckhaus J, Friedrich C, Boekhoff S, et al.: Outcome after pediatric craniopharyngioma: the role of age at diagnosis and hypothalamic damage. Eur J Endocrinol 188 (3): , 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Apps JR, Muller HL, Hankinson TC, et al.: Contemporary Biological Insights and Clinical Management of Craniopharyngioma. Endocr Rev 44 (3): 518-538, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Müller HL: Childhood craniopharyngioma: current controversies on management in diagnostics, treatment and follow-up. Expert Rev Neurother 10 (4): 515-24, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bogusz A, Müller HL: Childhood-onset craniopharyngioma: latest insights into pathology, diagnostics, treatment, and follow-up. Expert Rev Neurother 18 (10): 793-806, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Winkfield KM, Tsai HK, Yao X, et al.: Long-term clinical outcomes following treatment of childhood craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 56 (7): 1120-6, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Giese H, Haenig B, Haenig A, et al.: Neurological and neuropsychological outcome after resection of craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosurg 132 (5): 1425-1434, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Özyurt J, Thiel CM, Lorenzen A, et al.: Neuropsychological outcome in patients with childhood craniopharyngioma and hypothalamic involvement. J Pediatr 164 (4): 876-881.e4, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Merchant TE, Hoehn ME, Khan RB, et al.: Proton therapy and limited surgery for paediatric and adolescent patients with craniopharyngioma (RT2CR): a single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 24 (5): 523-534, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wan MJ, Zapotocky M, Bouffet E, et al.: Long-term visual outcomes of craniopharyngioma in children. J Neurooncol 137 (3): 645-651, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Vinchon M, Weill J, Delestret I, et al.: Craniopharyngioma and hypothalamic obesity in children. Childs Nerv Syst 25 (3): 347-52, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dolson EP, Conklin HM, Li C, et al.: Predicting behavioral problems in craniopharyngioma survivors after conformal radiation therapy. Pediatr Blood Cancer 52 (7): 860-4, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kawamata T, Amano K, Aihara Y, et al.: Optimal treatment strategy for craniopharyngiomas based on long-term functional outcomes of recent and past treatment modalities. Neurosurg Rev 33 (1): 71-81, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Müller HL: Consequences of craniopharyngioma surgery in children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96 (7): 1981-91, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Marcus HJ, Rasul FT, Hussein Z, et al.: Craniopharyngioma in children: trends from a third consecutive single-center cohort study. J Neurosurg Pediatr 25 (3): 242-250, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Clark AJ, Cage TA, Aranda D, et al.: Treatment-related morbidity and the management of pediatric craniopharyngioma: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Pediatr 10 (4): 293-301, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lohkamp LN, Kasper EM, Pousa AE, et al.: An update on multimodal management of craniopharyngioma in children. Front Oncol 13: 1149428, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Boekhoff S, Bogusz A, Sterkenburg AS, et al.: Long-term Effects of Growth Hormone Replacement Therapy in Childhood-onset Craniopharyngioma: Results of the German Craniopharyngioma Registry (HIT-Endo). Eur J Endocrinol 179 (5): 331-341, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Nguyen Quoc A, Beccaria K, González Briceño L, et al.: GH and Childhood-onset Craniopharyngioma: When to Initiate GH Replacement Therapy? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 108 (8): 1929-1936, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Heinks K, Boekhoff S, Hoffmann A, et al.: Quality of life and growth after childhood craniopharyngioma: results of the multinational trial KRANIOPHARYNGEOM 2007. Endocrine 59 (2): 364-372, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Boguszewski MCS, Boguszewski CL, Chemaitilly W, et al.: Safety of growth hormone replacement in survivors of cancer and intracranial and pituitary tumours: a consensus statement. Eur J Endocrinol 186 (6): P35-P52, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Elowe-Gruau E, Beltrand J, Brauner R, et al.: Childhood craniopharyngioma: hypothalamus-sparing surgery decreases the risk of obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98 (6): 2376-82, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hoffmann A, Bootsveld K, Gebhardt U, et al.: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and fatigue in long-term survivors of childhood-onset craniopharyngioma. Eur J Endocrinol 173 (3): 389-97, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tan TS, Patel L, Gopal-Kothandapani JS, et al.: The neuroendocrine sequelae of paediatric craniopharyngioma: a 40-year meta-data analysis of 185 cases from three UK centres. Eur J Endocrinol 176 (3): 359-369, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Otte A, Müller HL: Childhood-onset Craniopharyngioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 106 (10): e3820-e3836, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kiehna EN, Merchant TE: Radiation therapy for pediatric craniopharyngioma. Neurosurg Focus 28 (4): E10, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lo AC, Howard AF, Nichol A, et al.: A Cross-Sectional Cohort Study of Cerebrovascular Disease and Late Effects After Radiation Therapy for Craniopharyngioma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 63 (5): 786-93, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lucas JT, Faught AM, Hsu CY, et al.: Pre- and Posttherapy Risk Factors for Vasculopathy in Pediatric Patients With Craniopharyngioma Treated With Surgery and Proton Radiation Therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 113 (1): 152-160, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Burman P, van Beek AP, Biller BM, et al.: Radiotherapy, Especially at Young Age, Increases the Risk for De Novo Brain Tumors in Patients Treated for Pituitary/Sellar Lesions. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102 (3): 1051-1058, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

Latest Updates to This Summary (11/26/2024)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

Treatment of Newly Diagnosed Childhood Craniopharyngioma

Added text to state that a report from the prospective registry study KiProReg examined the use of proton-beam therapy in 84 children younger than 18 years with craniopharyngioma. The estimated 3-year overall survival rate was 98.2%, and the progression-free survival rate was 94.7%. With a median follow-up of 4.3 years, late toxicities appeared acceptable. Sixty-three of the patients were treated with pencil-beam scanning, which is considered an advancement in proton technology (cited Bischoff et al. as reference 43).

Late Effects in Patients Treated for Childhood Craniopharyngioma

Added Nguyen Quoc et al. as reference 20.

This summary is written and maintained by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of NCI. The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or NIH. More information about summary policies and the role of the PDQ Editorial Boards in maintaining the PDQ summaries can be found on the About This PDQ Summary and PDQ® Cancer Information for Health Professionals pages.

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of childhood craniopharyngioma. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewers for Childhood Craniopharyngioma Treatment are:

- Kenneth J. Cohen, MD, MBA (Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins Hospital)

- Karen J. Marcus, MD, FACR (Dana-Farber of Boston Children's Cancer Center and Blood Disorders Harvard Medical School)

- Roger J. Packer, MD (Children's National Hospital)

- D. Williams Parsons, MD, PhD (Texas Children's Hospital)

- Malcolm A. Smith, MD, PhD (National Cancer Institute)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's Email Us. Do not contact the individual Board Members with questions or comments about the summaries. Board members will not respond to individual inquiries.

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board uses a formal evidence ranking system in developing its level-of-evidence designations.

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as “NCI’s PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary].”

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Childhood Craniopharyngioma Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/brain/hp/child-cranio-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389330]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in Visuals Online, a collection of over 2,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

Based on the strength of the available evidence, treatment options may be described as either “standard” or “under clinical evaluation.” These classifications should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website’s Email Us.