Esophageal Cancer Screening (PDQ®)–Patient Version

What Is Screening?

Screening is looking for cancer before a person has any symptoms. This can help find cancer at an early stage. When abnormal tissue or cancer is found early, it may be easier to treat. By the time symptoms appear, cancer may have begun to spread.

Scientists are trying to better understand which people are more likely to get certain types of cancer. They also study the things we do and the things around us to see if they cause cancer. This information helps doctors recommend who should be screened for cancer, which screening tests should be used, and how often the tests should be done.

It is important to remember that your doctor does not necessarily think you have cancer if he or she suggests a screening test. Screening tests are given when you have no cancer symptoms.

If a screening test result is abnormal, you may need to have more tests done to find out if you have cancer. These are called diagnostic tests.

General Information About Esophageal Cancer

Key Points

- Esophageal cancer is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in the tissues of the esophagus.

- Esophageal cancer is found more often in men.

- Smoking, heavy alcohol use, and Barrett esophagus can affect the risk of developing esophageal cancer.

Esophageal cancer is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in the tissues of the esophagus.

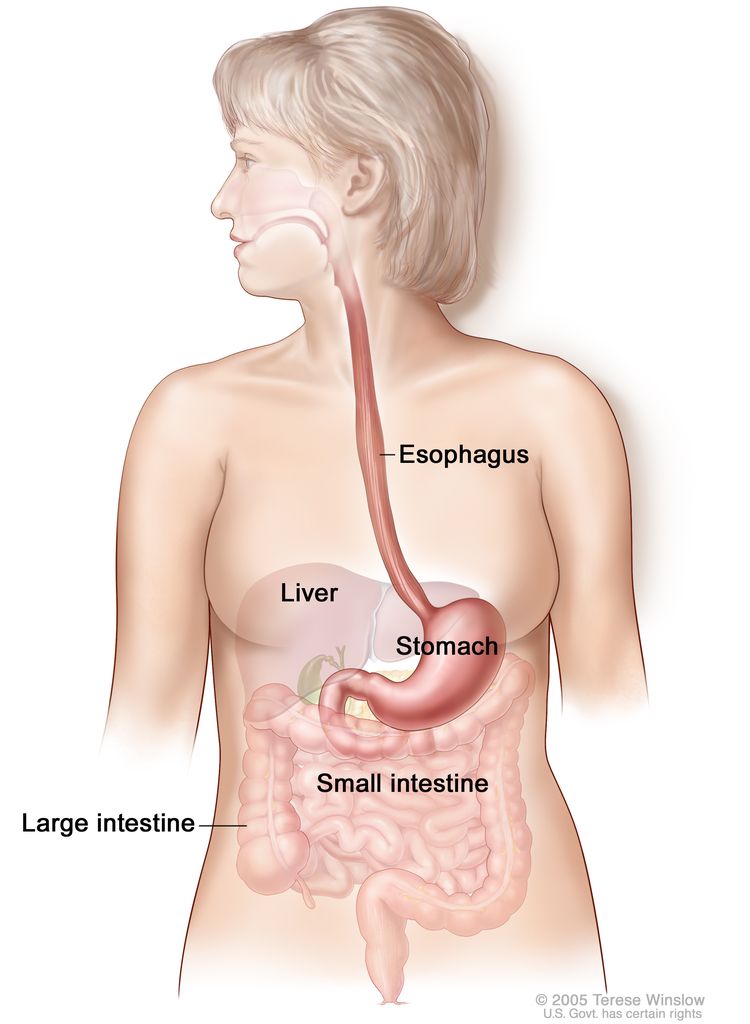

The esophagus is the hollow, muscular tube that moves food and

liquid from the throat to the stomach. The wall of the esophagus is made up of several tissue layers,

including mucous membrane, muscle, and connective tissue. Esophageal cancer

starts in the inside lining of the esophagus and spreads outward through the

other layers as it grows.

The two most common types of esophageal cancer are named for the type of cells that become cancerous:

- Squamous cell carcinoma: Cancer forms in the thin, flat cells lining the inside of the esophagus. This cancer is most often found in the upper and middle part of the esophagus but can occur anywhere along the esophagus. This is also called epidermoid carcinoma.

- Adenocarcinoma: Cancer begins in glandular cells. Glandular cells in the lining of the esophagus produce and release fluids such as mucus. Adenocarcinoma usually forms in the lower part of the esophagus, near the stomach.

Other PDQ summaries containing information related to esophageal cancer include:

Esophageal cancer is found more often in men.

Men are about four times more likely than women to develop esophageal cancer. There are more new cases of esophageal adenocarcinoma each year and fewer new cases of squamous cell carcinoma. Although the rates of squamous cell carcinoma are declining overall, they remain much higher in Black men than in White men. The chance of developing esophageal cancer increases with age in all racial and ethnic groups. White men are more likely to develop esophageal cancer at higher rates than Black men in all age groups. In women, the rates of developing this disease are higher in Black women until age 74 years, after which White women have higher rates.

Smoking, heavy alcohol use, and Barrett esophagus can affect the risk of developing esophageal cancer.

Anything that increases the chance of getting a disease is called a risk factor. Having a risk factor does not mean that you will get cancer; not having risk factors doesn’t mean that you will not get cancer. People who think they may be at risk should discuss this with their doctor.

Risk factors for squamous cell esophageal cancer include:

- using tobacco

- drinking a lot of alcohol

- being malnourished (lacking nutrients and/or calories)

- having a human papillomavirus (HPV) infection

- having tylosis (a rare inherited disorder that causes thickening of the skin on the hands and feet and is associated with an increased risk of squamous cell esophageal cancer)

- having achalasia (a rare condition that affects the ability of food and liquids to pass from the esophagus into the stomach)

- having swallowed lye (a chemical found in some cleaning fluids)

- drinking very hot liquids on a regular basis

Risk factors for esophageal adenocarcinoma include:

- having gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- having Barrett esophagus

- having a history of using drugs that relax the lower esophageal sphincter (the ring of muscle that opens and closes the opening between the esophagus and the stomach)

- having excess body weight (overweight)

Esophageal Cancer Screening

Key Points

- Tests are used to screen for different types of cancer when a person does not have symptoms.

- There is no standard or routine screening test for esophageal cancer.

- Esophagoscopy

- Biopsy

- Brush cytology

- Balloon cytology

- Chromoendoscopy

- Fluorescence spectroscopy

- Screening tests for esophageal cancer are being studied in clinical trials.

Tests are used to screen for different types of cancer when a person does not have symptoms.

Scientists study screening tests to find those with the fewest harms and most benefits. Cancer screening trials also are meant to show whether early detection (finding cancer before it causes symptoms) helps a person live longer or decreases a person's chance of dying from the disease. For some types of cancer, the chance of recovery is better if the disease is found and treated at an early stage.

There is no standard or routine screening test for esophageal cancer.

Although there are no standard or routine screening tests for esophageal cancer, the following tests are being used or studied to screen for it:

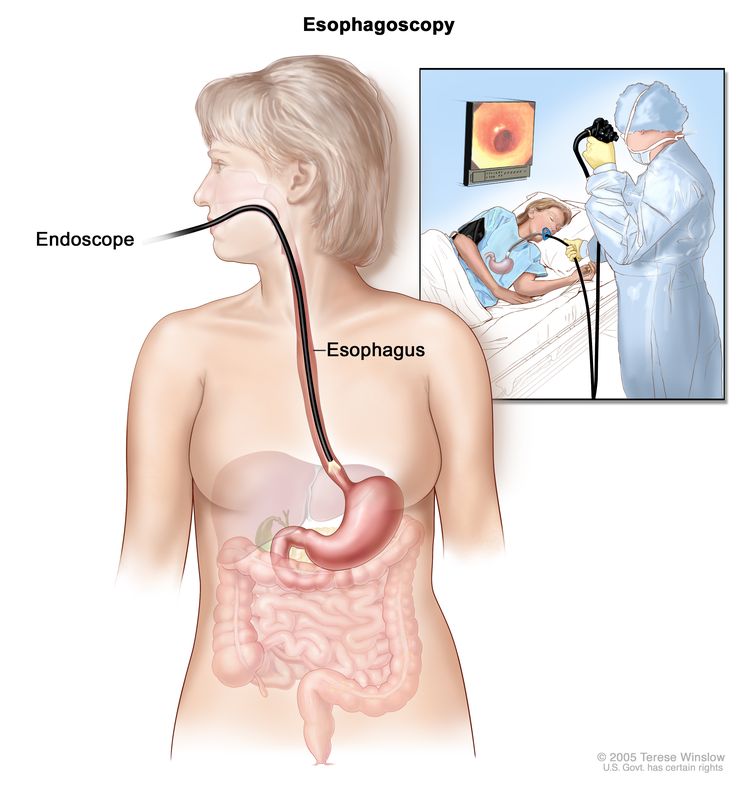

Esophagoscopy

A procedure to look inside the esophagus to check for abnormal areas. An esophagoscope is inserted through the mouth or nose and down the throat into the esophagus. An esophagoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove tissue samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer.

Biopsy

The removal of cells or tissues so they can be viewed under a microscope by a pathologist to check for signs of cancer. Taking biopsy samples from several different areas in the lining of the lower part of the esophagus may detect early Barrett esophagus. This procedure may be used for patients who have risk factors for Barrett esophagus.

Brush cytology

A procedure in which cells are brushed from the lining of the esophagus and viewed under a microscope to see if they are abnormal. This may be done during an esophagoscopy.

Balloon cytology

A procedure in which cells are collected from the lining of the esophagus using a deflated balloon that is swallowed by the patient. The balloon is then inflated and pulled out of the esophagus. Esophageal cells on the balloon are viewed under a microscope to see if they are abnormal.

Chromoendoscopy

A procedure in which a dye is sprayed onto the lining of the esophagus during esophagoscopy. Increased staining of certain areas of the lining may be a sign of early Barrett esophagus.

Fluorescence spectroscopy

A procedure that uses a special light to view tissue in the lining of the esophagus. The light probe is passed through an endoscope and shines on the lining of the esophagus. The light given off by the cells lining the esophagus is then measured. Malignant tissue gives off less light than normal tissue.

Screening tests for esophageal cancer are being studied in clinical trials.

Information about clinical trials supported by NCI can be found on NCI’s clinical trials search webpage. Clinical trials supported by other organizations can be found on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

Risks of Esophageal Cancer Screening

Key Points

- Screening tests have risks.

- The risks of esophageal cancer screening tests include:

- Finding esophageal cancer may not improve health or help a person live longer.

- False-negative test results can occur.

- False-positive test results can occur.

- Side effects may be caused by the test itself.

Screening tests have risks.

Decisions about screening tests can be difficult. Not all screening tests are helpful, and most have risks. Before having any screening test, you may want to discuss the test with your doctor. It is important to know the risks of the test and whether it has been proven to reduce the risk of dying from cancer.

The risks of esophageal cancer screening tests include:

Finding esophageal cancer may not improve health or help a person live longer.

Screening may not improve your health or help you live longer if you have advanced esophageal cancer or if it has already spread to other places in your body.

Some cancers never cause symptoms or become life-threatening, but if found by a screening test, the cancer may be treated. It is not known if treatment of these cancers will help you live longer than if no treatment were given, and treatments for cancer may have serious side effects.

False-negative test results can occur.

Screening test results may appear to be normal even though esophageal cancer is present. A person who receives a false-negative test result (one that shows there is no cancer when there really is) may delay seeking medical care even if there are symptoms.

False-positive test results can occur.

Screening test results may appear to be abnormal even though no cancer is present. A false-positive test result (one that shows there is cancer when there really isn't) can cause anxiety and is usually followed by more tests (such as biopsy), which also have risks.

Side effects may be caused by the test itself.

There are rare but serious side effects that may occur with esophagoscopy and biopsy. These include:

About This PDQ Summary

About PDQ

Physician Data Query (PDQ) is the National Cancer Institute's (NCI's) comprehensive cancer information database. The PDQ database contains summaries of the latest published information on cancer prevention, detection, genetics, treatment, supportive care, and complementary and alternative medicine. Most summaries come in two versions. The health professional versions have detailed information written in technical language. The patient versions are written in easy-to-understand, nontechnical language. Both versions have cancer information that is accurate and up to date and most versions are also available in Spanish.

PDQ is a service of the NCI. The NCI is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH is the federal government’s center of biomedical research. The PDQ summaries are based on an independent review of the medical literature. They are not policy statements of the NCI or the NIH.

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary has current information about esophageal cancer screening. It is meant to inform and help patients, families, and caregivers. It does not give formal guidelines or recommendations for making decisions about health care.

Reviewers and Updates

Editorial Boards write the PDQ cancer information summaries and keep them up to date. These Boards are made up of experts in cancer treatment and other specialties related to cancer. The summaries are reviewed regularly and changes are made when there is new information. The date on each summary ("Updated") is the date of the most recent change.

The information in this patient summary was taken from the health professional version, which is reviewed regularly and updated as needed, by the PDQ Screening and Prevention Editorial Board.

Clinical Trial Information

A clinical trial is a study to answer a scientific question, such as whether one treatment is better than another. Trials are based on past studies and what has been learned in the laboratory. Each trial answers certain scientific questions in order to find new and better ways to help cancer patients. During treatment clinical trials, information is collected about the effects of a new treatment and how well it works. If a clinical trial shows that a new treatment is better than one currently being used, the new treatment may become "standard." Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Clinical trials can be found online at NCI's website. For more information, call the Cancer Information Service (CIS), NCI's contact center, at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237).

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. The content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text. It cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless the whole summary is shown and it is updated regularly. However, a user would be allowed to write a sentence such as “NCI’s PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks in the following way: [include excerpt from the summary].”

The best way to cite this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Screening and Prevention Editorial Board. PDQ Esophageal Cancer Screening. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/esophageal/patient/esophageal-screening-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389194]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use in the PDQ summaries only. If you want to use an image from a PDQ summary and you are not using the whole summary, you must get permission from the owner. It cannot be given by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the images in this summary, along with many other images related to cancer can be found in Visuals Online. Visuals Online is a collection of more than 3,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

The information in these summaries should not be used to make decisions about insurance reimbursement. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website’s E-mail Us.