Pancreatic Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version

General Information About Pancreatic Cancer

This summary provides information about the treatment of exocrine pancreatic cancer.

Incidence and Mortality

Estimated new cases and deaths from pancreatic cancer in the United States in 2025:[1]

- New cases: 67,440.

- Deaths: 51,980.

The incidence of pancreatic cancer has markedly increased over the past several decades. In the United States, it ranks as the fourth leading cause of cancer death in men and the third leading cause of cancer death in women.[1] Despite the high mortality rate associated with pancreatic cancer, its etiology is poorly understood.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for development of pancreatic cancer include:[2,3]

- A family history of pancreatic cancer.

- Cigarette smoking.

- Obesity.

- Chronic pancreatitis.

- Certain genetic disorders (such as those associated with the BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, and ATM genes).

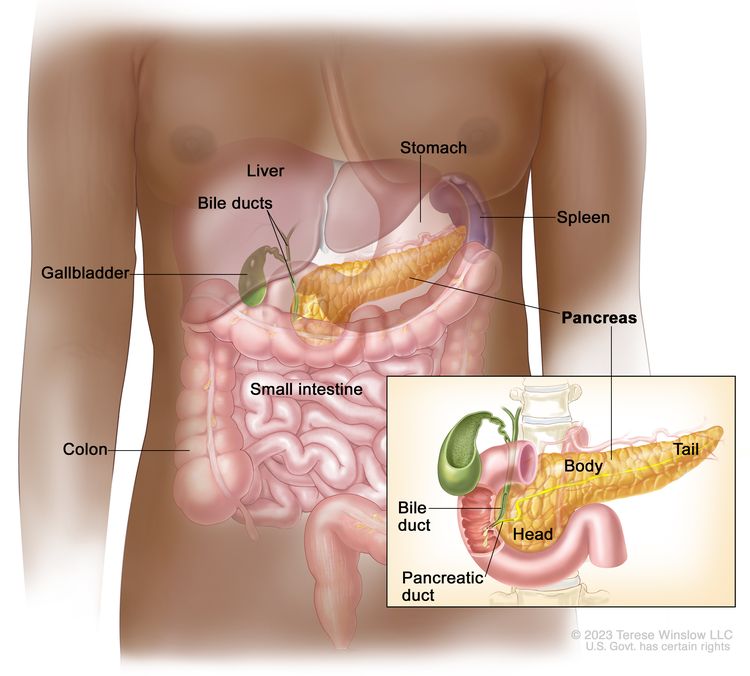

Anatomy

Cancers of the pancreas are commonly identified by the site of involvement within the pancreas. Surgical approaches differ for masses in the head, body, tail, or uncinate process of the pancreas.

Clinical Features

Pancreatic cancer symptoms depend on the site of the tumor within the pancreas and the degree of tumor involvement.

In the early stages of pancreatic cancer, there are not many noticeable symptoms. As the cancer grows, symptoms may include:

- Jaundice.

- Light-colored stools or dark urine.

- Pain in the upper or middle abdomen and back.

- Weight loss for no known reason.

- Loss of appetite.

- Fatigue.

Diagnostic and Staging Evaluation

Pancreatic cancer is difficult to detect and diagnose for the following reasons:

- There are no noticeable signs or symptoms in the early stages of pancreatic cancer.

- The signs of pancreatic cancer, when present, are like the signs of many other illnesses, such as pancreatitis or an ulcer.

- The pancreas is obscured by other organs in the abdomen and is difficult to visualize clearly on imaging tests.

To appropriately treat pancreatic cancer, it is crucial to evaluate whether the cancer can be resected.

Imaging

Imaging tests may help diagnose pancreatic cancer and identify patients with disease that is not amenable to resection. Imaging tests may include:[4]

Peritoneal cytology

In a case series of 228 patients, positive peritoneal cytology had a positive predictive value of 94%, specificity of 98%, and sensitivity of 25% for determining unresectability.[7]

Tumor markers

No tumor-specific markers exist for pancreatic cancer. Markers such as serum cancer antigen (CA) 19-9 have low specificity. Most patients with pancreatic cancer have an elevated CA 19-9 level at diagnosis. Increased CA 19-9 levels during or after definitive therapy may identify patients with progressive tumor growth.[8][Level of evidence C2] However, the presence of a normal CA 19-9 level does not preclude recurrence.

Prognosis and Survival

The primary factors that influence prognosis are:

- Whether the tumor is localized and can be completely resected.

- Whether the tumor has spread to lymph nodes or elsewhere.

Exocrine pancreatic cancer is rarely curable and has an overall survival (OS) rate of less than 6%.[9] Pancreatic cancer is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, and treatment decisions are complex. Management with a comprehensive multidisciplinary team should be considered.

The highest cure rate occurs when the tumor is truly localized to the pancreas; however, this stage of disease accounts for less than 20% of cases. For patients with localized disease and small cancers (<2 cm) with no lymph node metastases and no extension beyond the capsule of the pancreas, complete surgical resection is associated with an actuarial 5-year survival rate of 18% to 24%.[10][Level of evidence C1]

Surgical resection is the mainstay of curative treatment and provides a survival benefit in patients with small, localized pancreatic tumors, but it should be considered only alongside systemic therapy. Patients with unresectable, metastatic, or recurrent disease are unlikely to benefit from surgical resection.

Patients with any stage of pancreatic cancer are candidates for clinical trials because of the poor response to chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgery as conventionally used.

Information about ongoing clinical trials for pancreatic cancer is available from the NCI website.

Palliative Therapy

Palliation of symptoms may be achieved with conventional treatment (systemic chemotherapy).

Palliative measures that may improve quality of life without affecting OS include:[11,12]

- Surgical or radiological biliary decompression.

- Relief of gastric outlet obstruction.

- Pain control.

- Psychological care to address the potentially disabling psychological events associated with the diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer.[13]

References

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2025. American Cancer Society, 2025. Available online. Last accessed January 16, 2025.

- Tersmette AC, Petersen GM, Offerhaus GJ, et al.: Increased risk of incident pancreatic cancer among first-degree relatives of patients with familial pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 7 (3): 738-44, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Nöthlings U, Wilkens LR, Murphy SP, et al.: Meat and fat intake as risk factors for pancreatic cancer: the multiethnic cohort study. J Natl Cancer Inst 97 (19): 1458-65, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Riker A, Libutti SK, Bartlett DL: Advances in the early detection, diagnosis, and staging of pancreatic cancer. Surg Oncol 6 (3): 157-69, 1997. [PUBMED Abstract]

- John TG, Greig JD, Carter DC, et al.: Carcinoma of the pancreatic head and periampullary region. Tumor staging with laparoscopy and laparoscopic ultrasonography. Ann Surg 221 (2): 156-64, 1995. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Minnard EA, Conlon KC, Hoos A, et al.: Laparoscopic ultrasound enhances standard laparoscopy in the staging of pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg 228 (2): 182-7, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Merchant NB, Conlon KC, Saigo P, et al.: Positive peritoneal cytology predicts unresectability of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Am Coll Surg 188 (4): 421-6, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Willett CG, Daly WJ, Warshaw AL: CA 19-9 is an index of response to neoadjunctive chemoradiation therapy in pancreatic cancer. Am J Surg 172 (4): 350-2, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin 63 (1): 11-30, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Yeo CJ, Abrams RA, Grochow LB, et al.: Pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: postoperative adjuvant chemoradiation improves survival. A prospective, single-institution experience. Ann Surg 225 (5): 621-33; discussion 633-6, 1997. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, et al.: Surgical palliation of unresectable periampullary adenocarcinoma in the 1990s. J Am Coll Surg 188 (6): 658-66; discussion 666-9, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Baron TH: Expandable metal stents for the treatment of cancerous obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract. N Engl J Med 344 (22): 1681-7, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Passik SD, Breitbart WS: Depression in patients with pancreatic carcinoma. Diagnostic and treatment issues. Cancer 78 (3 Suppl): 615-26, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

Cellular Classification of Pancreatic Cancer

Pancreatic cancer includes the following carcinomas:

Malignant

- Duct cell carcinoma (90% of all cases).

- Acinar cell carcinoma.

- Adenosquamous carcinoma.

- Cystadenocarcinoma (serous and mucinous types).

- Giant cell carcinoma.

- Invasive adenocarcinoma associated with cystic mucinous neoplasm or intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm.

- Mixed type (ductal-endocrine or acinar-endocrine).

- Mucinous carcinoma.

- Pancreatoblastoma.

- Papillary-cystic neoplasm (Frantz tumor). This tumor has lower malignant potential and may be cured with surgery alone.[1,2]

- Papillary mucinous carcinoma.

- Signet ring carcinoma.

- Small cell carcinoma.

- Unclassified.

- Undifferentiated carcinoma.

Borderline Malignancies

- Intraductal papillary mucinous tumor with dysplasia.[3]

- Mucinous cystic tumor with dysplasia.

- Pseudopapillary solid tumor.

References

- Sanchez JA, Newman KD, Eichelberger MR, et al.: The papillary-cystic neoplasm of the pancreas. An increasingly recognized clinicopathologic entity. Arch Surg 125 (11): 1502-5, 1990. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Warshaw AL, Compton CC, Lewandrowski K, et al.: Cystic tumors of the pancreas. New clinical, radiologic, and pathologic observations in 67 patients. Ann Surg 212 (4): 432-43; discussion 444-5, 1990. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, et al.: Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas: an increasingly recognized clinicopathologic entity. Ann Surg 234 (3): 313-21; discussion 321-2, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

Stage Information for Pancreatic Cancer

The staging system for pancreatic exocrine cancer continues to evolve. Clinical staging is guided by resectability, which is strongly influenced by surgical judgment. Consensus guidelines for surgical resectability (e.g., National Comprehensive Cancer Network, MD Anderson Cancer Center, American Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association, and International Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association) continue to be refined, but are traditionally stratified by the following tumor characteristics:

- Resectable: tumors without vascular involvement.

- Borderline resectable: tumors with involvement of vasculature, involvement of local structures, or other evidence of a high risk of R1 resection.

- Locally advanced: tumors with local invasion (primarily vascular involvement) that preclude surgical intervention.

- Metastatic: cancer that has spread beyond the primary pancreatic tumor to other organs.

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) has designated staging by TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) classification.[1]

AJCC Stage Groupings and TNM Definitions

| Stage | TNM | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis. | |||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Exocrine Pancreas. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 337–47. | |||

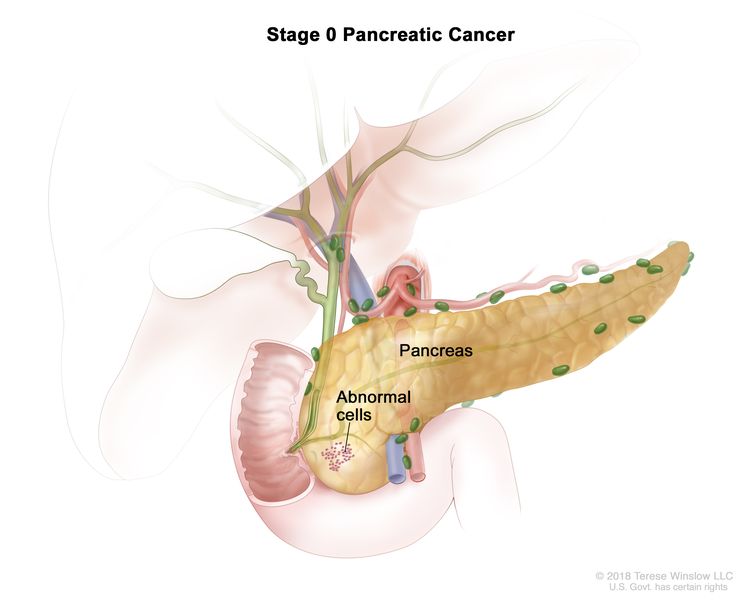

| 0 | Tis, N0, M0 | Tis = Carcinoma in situ. This includes high-grade pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIn-3), intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with high-grade dysplasia, intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm with high-grade dysplasia, and mucinous cystic neoplasm with high-grade dysplasia. |

|

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastases. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

| Stage | TNM | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis. | |||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Exocrine Pancreas. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 337–47. | |||

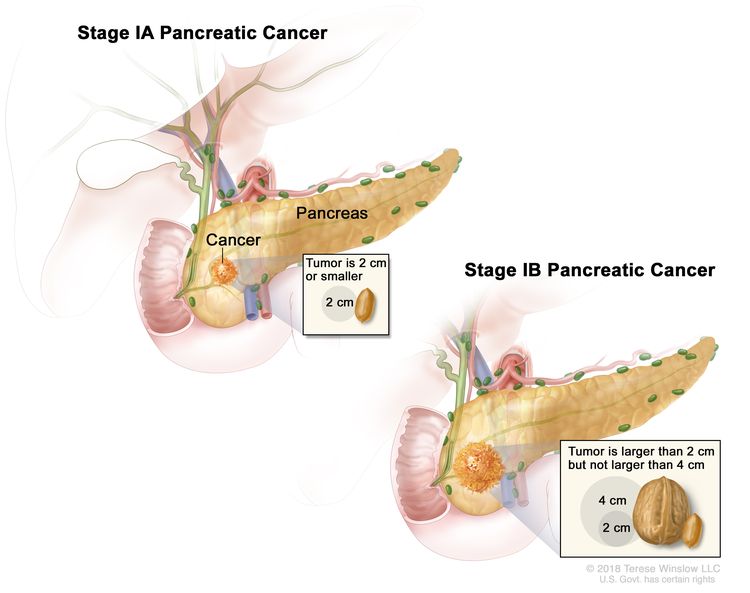

| IA | T1, N0, M0 | T1 = Tumor ≤2 cm in greatest dimension. |

|

| –T1a = Tumor ≤0.5 cm in greatest dimension. | |||

| –T1b = Tumor >0.5 cm and <1 cm in greatest dimension. | |||

| –T1c = Tumor 1–2 cm in greatest dimension. | |||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastases. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

| IB | T2, N0, M0 | T2 = Tumor >2 cm and ≤4 cm in greatest dimension. | |

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastases. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

| Stage | TNM | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis. | |||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Exocrine Pancreas. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 337–47. | |||

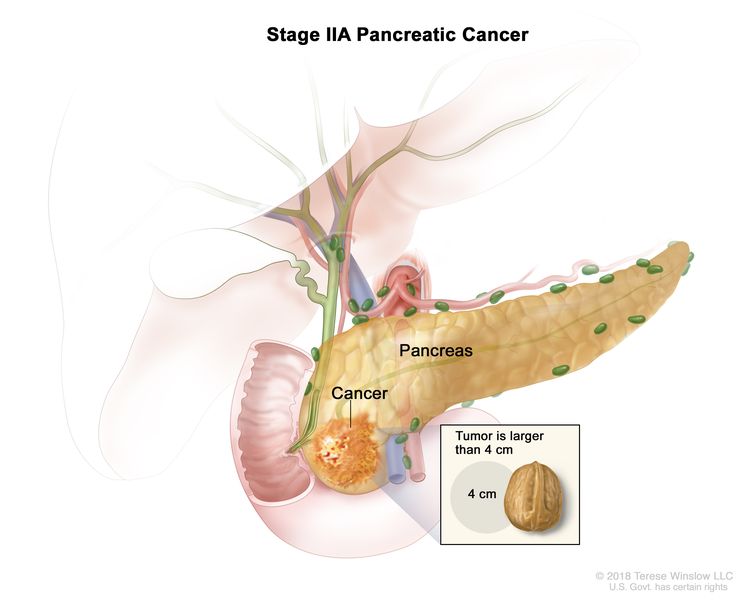

| IIA | T3, N0, M0 | T3 = Tumor >4 cm in greatest dimension. |

|

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastases. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

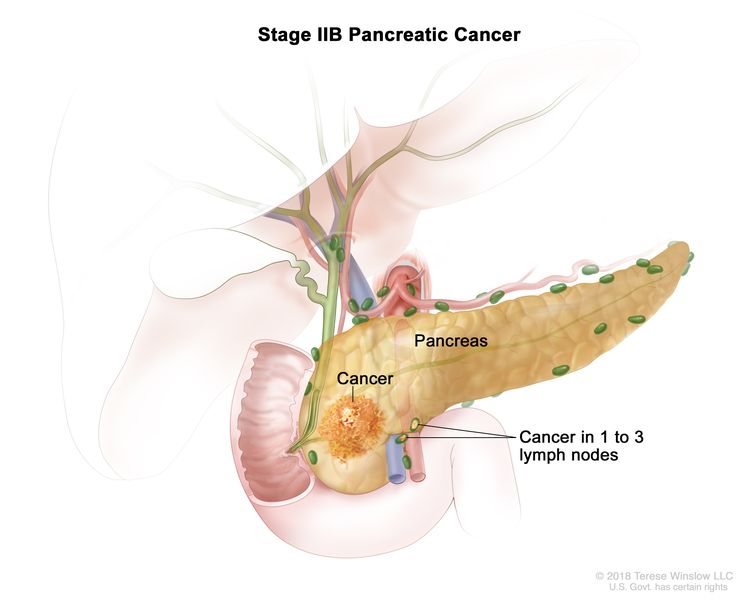

| IIB | T1, N1, M0 | T1 = Tumor ≤2 cm in greatest dimension. |

|

| –T1a = Tumor ≤0.5 cm in greatest dimension. | |||

| –T1b = Tumor >0.5 cm and <1 cm in greatest dimension. | |||

| –T1c = Tumor 1–2 cm in greatest dimension. | |||

| N1 = Metastasis in one to three regional lymph nodes. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

| T2, N1, M0 | T2 = Tumor >2 cm and ≤4 cm in greatest dimension. | ||

| N1 = Metastasis in one to three regional lymph nodes. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

| T3, N1, M0 | T3 = Tumor >4 cm in greatest dimension. | ||

| N1 = Metastasis in one to three regional lymph nodes. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

| Stage | TNM | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis. | |||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Exocrine Pancreas. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 337–47. | |||

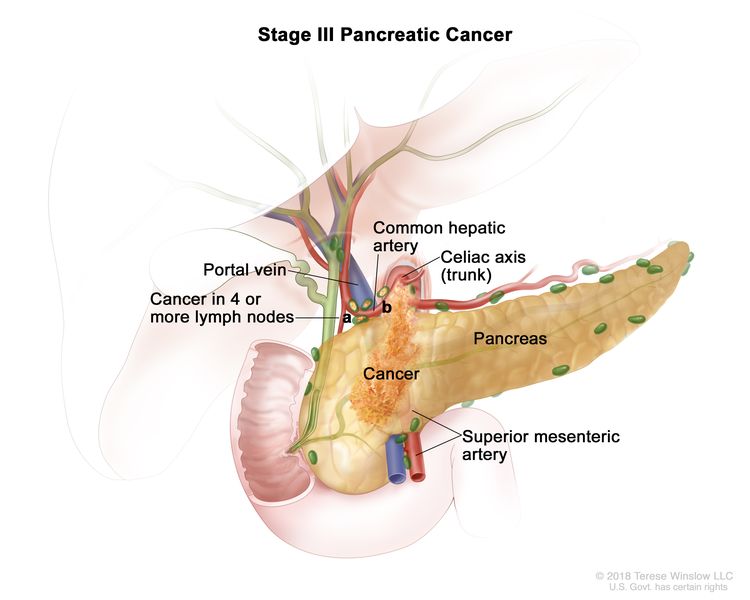

| III | T1, N2, M0 | T1 = Tumor ≤2 cm in greatest dimension. |

|

| –T1a = Tumor ≤0.5 cm in greatest dimension. | |||

| –T1b = Tumor >0.5 cm and <1 cm in greatest dimension. | |||

| –T1c = Tumor 1–2 cm in greatest dimension. | |||

| N2 = Metastasis in four or more regional lymph nodes. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

| T2, N2, M0 | T2 = Tumor >2 cm and ≤4 cm in greatest dimension. | ||

| N2 = Metastasis in four or more regional lymph nodes. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

| T3, N2, M0 | T3 = Tumor >4 cm in greatest dimension. | ||

| N2 = Metastasis in four or more regional lymph nodes. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

| T4, Any N, M0 | T4 = Tumor involves celiac axis, superior mesenteric artery, and/or common hepatic artery, regardless of size. | ||

| NX = Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed. | |||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastases. | |||

| N1 = Metastasis in one to three regional lymph nodes. | |||

| N2 = Metastasis in four or more regional lymph nodes. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

| Stage | TNM | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis. | |||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Exocrine Pancreas. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 337–47. | |||

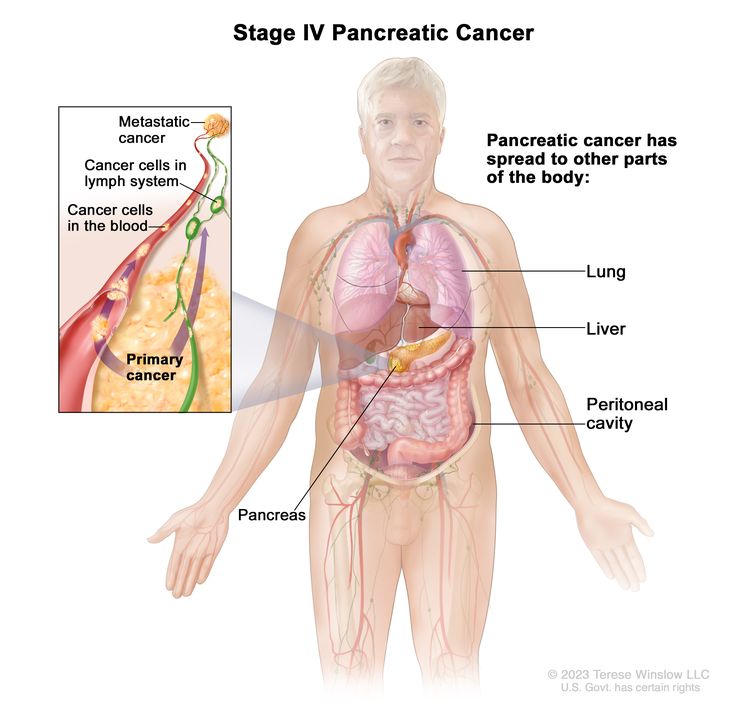

| IV | Any T, Any N, M1 | TX = Primary tumor cannot be assessed. |

|

| T0 = No evidence of primary tumor. | |||

| Tis = Carcinoma in situ. This includes high-grade pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIn-3), intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm with high-grade dysplasia, intraductal tubulopapillary neoplasm with high-grade dysplasia, and mucinous cystic neoplasm with high-grade dysplasia. | |||

| T1 = Tumor ≤2 cm in greatest dimension. | |||

| –T1a = Tumor ≤0.5 cm in greatest dimension. | |||

| –T1b = Tumor >0.5 cm and <1 cm in greatest dimension. | |||

| –T1c = Tumor 1–2 cm in greatest dimension. | |||

| T2 = Tumor >2 cm and ≤4 cm in greatest dimension. | |||

| T3 = Tumor >4 cm in greatest dimension. | |||

| T4 = Tumor involves celiac axis, superior mesenteric artery, and/or common hepatic artery, regardless of size. | |||

| NX = Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed. | |||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastases. | |||

| N1 = Metastasis in one to three regional lymph nodes. | |||

| N2 = Metastasis in four or more regional lymph nodes. | |||

| M1 = Distant metastasis. | |||

References

- Kakar S, Pawlik TM, Allen PJ: Exocrine Pancreas. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp. 337–47.

Treatment Option Overview for Pancreatic Cancer

Surgical resection, when feasible, remains the primary treatment modality for patients with pancreatic cancer. On occasion, resection can lead to long-term survival, and it provides effective palliation.[1-3][Level of evidence C1] Treatment is often guided by resectability, but this may vary depending on surgical judgment and experience. Referral to a high-volume center should be considered.[4]

Postoperative chemotherapy improves overall survival, but the role of chemoradiation remains controversial.

Complications of pancreatic cancer include:

- Malabsorption: Frequently, malabsorption caused by exocrine insufficiency contributes to malnutrition. Pancreatic enzyme replacement can help alleviate this problem.

- Pain: Celiac axis and intrapleural nerve blocks can provide highly effective and long-lasting control of pain for some patients. For more information, see Cancer Pain.

The survival rate of patients with any stage of pancreatic exocrine cancer is poor. Clinical trials are appropriate for patients with any stage of disease and should be considered before palliative approaches are selected.

Information about ongoing clinical trials for pancreatic cancer is available from the NCI website.

| Clinical Stage | Treatment Options |

|---|---|

| Resectable or borderline resectable pancreatic cancer | Neoadjuvant therapy |

| Surgery | |

| Postoperative chemotherapy | |

| Postoperative chemoradiation therapy | |

| Preoperative chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy (under clinical evaluation) | |

| Alternative radiation techniques (under clinical evaluation) | |

| Locally advanced pancreatic cancer | Chemotherapy with or without targeted therapy |

| Chemoradiation therapy | |

| Surgery | |

| Palliative surgery | |

| Clinical trials evaluating novel agents in combination with chemotherapy or chemoradiation therapy for patients with unresectable tumors | |

| Intraoperative radiation therapy and/or implantation of radioactive sources (under clinical evaluation) | |

| Metastatic or recurrent pancreatic cancer | Chemotherapy with or without targeted therapy |

| Clinical trials evaluating new anticancer agents alone or in combination with chemotherapy |

Palliative therapies can be considered in patients with any stage of disease. For more information, see the Palliative Therapy section.

Capecitabine and Fluorouracil Dosing

The DPYD gene encodes an enzyme that catabolizes pyrimidines and fluoropyrimidines, like capecitabine and fluorouracil. An estimated 1% to 2% of the population has germline pathogenic variants in DPYD, which lead to reduced DPD protein function and an accumulation of pyrimidines and fluoropyrimidines in the body.[5,6] Patients with the DPYD*2A variant who receive fluoropyrimidines may experience severe, life-threatening toxicities that are sometimes fatal. Many other DPYD variants have been identified, with a range of clinical effects.[5-7] Fluoropyrimidine avoidance or a dose reduction of 50% may be recommended based on the patient's DPYD genotype and number of functioning DPYD alleles.[8-10] DPYD genetic testing costs less than $200, but insurance coverage varies due to a lack of national guidelines.[11] In addition, testing may delay therapy by 2 weeks, which would not be advisable in urgent situations. This controversial issue requires further evaluation.[12]

References

- Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, et al.: Pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer of the head of the pancreas. 201 patients. Ann Surg 221 (6): 721-31; discussion 731-3, 1995. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Conlon KC, Klimstra DS, Brennan MF: Long-term survival after curative resection for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clinicopathologic analysis of 5-year survivors. Ann Surg 223 (3): 273-9, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Yeo CJ, Abrams RA, Grochow LB, et al.: Pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: postoperative adjuvant chemoradiation improves survival. A prospective, single-institution experience. Ann Surg 225 (5): 621-33; discussion 633-6, 1997. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lidsky ME, Sun Z, Nussbaum DP, et al.: Going the Extra Mile: Improved Survival for Pancreatic Cancer Patients Traveling to High-volume Centers. Ann Surg 266 (2): 333-338, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sharma BB, Rai K, Blunt H, et al.: Pathogenic DPYD Variants and Treatment-Related Mortality in Patients Receiving Fluoropyrimidine Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 26 (12): 1008-1016, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lam SW, Guchelaar HJ, Boven E: The role of pharmacogenetics in capecitabine efficacy and toxicity. Cancer Treat Rev 50: 9-22, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Shakeel F, Fang F, Kwon JW, et al.: Patients carrying DPYD variant alleles have increased risk of severe toxicity and related treatment modifications during fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy. Pharmacogenomics 22 (3): 145-155, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Amstutz U, Henricks LM, Offer SM, et al.: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for Dihydropyrimidine Dehydrogenase Genotype and Fluoropyrimidine Dosing: 2017 Update. Clin Pharmacol Ther 103 (2): 210-216, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Henricks LM, Lunenburg CATC, de Man FM, et al.: DPYD genotype-guided dose individualisation of fluoropyrimidine therapy in patients with cancer: a prospective safety analysis. Lancet Oncol 19 (11): 1459-1467, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lau-Min KS, Varughese LA, Nelson MN, et al.: Preemptive pharmacogenetic testing to guide chemotherapy dosing in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies: a qualitative study of barriers to implementation. BMC Cancer 22 (1): 47, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Brooks GA, Tapp S, Daly AT, et al.: Cost-effectiveness of DPYD Genotyping Prior to Fluoropyrimidine-based Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Colon Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 21 (3): e189-e195, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Baker SD, Bates SE, Brooks GA, et al.: DPYD Testing: Time to Put Patient Safety First. J Clin Oncol 41 (15): 2701-2705, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Resectable or Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer

Treatment Options for Resectable or Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer

Treatment options for resectable or borderline resectable pancreatic cancer include:

- Neoadjuvant therapy: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without chemoradiation therapy.

- Surgery: Radical pancreatic resection including:

- Postoperative chemotherapy: Radical pancreatic resection followed by chemotherapy.[3]

- Postoperative chemoradiation therapy: Radical pancreatic resection followed by fluorouracil (5-FU) chemotherapy and radiation therapy.[4-8]

- Preoperative chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy (under clinical evaluation).

- Alternative radiation techniques (under clinical evaluation).

Palliative therapies can be considered in patients with any stage of disease. For more information, see the Palliative Therapy section.

Neoadjuvant therapy

Neoadjuvant therapy is chemotherapy with or without chemoradiation therapy given before surgery. The role of neoadjuvant therapy has been evaluated in retrospective studies (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results [SEER] Program database and National Cancer Database) and is recommended by multiple consensus guidelines for the management of patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. It is being evaluated in patients with resectable or borderline resectable pancreatic cancer in several ongoing trials.[9-11]

Evidence (neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without chemoradiation therapy):

- The phase II, multicenter, randomized A021501 trial (NCT02839343) enrolled 126 patients with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer from institutions in the National Clinical Trials Network cooperative groups between 2017 and 2019. Patients were assigned to receive either eight 2-week cycles of modified FOLFIRINOX (oxaliplatin, leucovorin, irinotecan, and 5-FU) (n = 65) or seven 2-week cycles of modified FOLFIRINOX followed by stereotactic body radiotherapy (33 Gy–40 Gy in 5 fractions) or hypofractionated image-guided radiotherapy (25 Gy in 5 fractions) (n = 55). Patients without disease progression then underwent surgery followed by four 2-week cycles of adjuvant FOLFOX6 (oxaliplatin, leucovorin, and 5-FU).[12]

- In the neoadjuvant chemotherapy-alone arm, the median overall survival (OS) was 29.8 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 21.1–36.6) with a 43% microscopically margin-negative (R0) resection rate. This was compared with estimated historical controls of median OS at 18 months.[12][Level of evidence C3]

- Grade 3 or greater treatment-related adverse events occurred in 57% of patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone.

- The neoadjuvant chemotherapy with radiation arm was closed at interim futility analysis because of low R0 resection rates (33%) in the first 30 patients enrolled.

- The multicenter phase III PREOPANC trial included 246 patients diagnosed with resectable or borderline resectable pancreatic cancer between 2013 and 2017. Patients at 16 Dutch centers were randomly assigned to receive either diagnostic laparoscopy, neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy, surgical resection, and four cycles of adjuvant gemcitabine or up-front surgery and six cycles of adjuvant gemcitabine. Neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy included the following: cycle 1 (21 days) with gemcitabine 1,000 mg/m2 on days 1 and 8; cycle 2 (28 days) with gemcitabine on days 1, 8, and 15 with 15 concurrent fractions of hypofractionated radiation (36 Gy) to the tumor and suspected associated lymph nodes; and cycle 3 (21 days) with gemcitabine on days 1 and 8.[13]

- The 5-year OS rate was 20.5% (95% CI, 14.2%–29.8%) for patients who received neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy and 6.5% (95% CI, 3.1%–13.7%) for patients who received up-front surgery (hazard ratio [HR], 0.73; 95% CI, 0.56–0.96; P = .025).[13][Level of evidence A1]

- The median OS was 15.7 months in the neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy group and 14.3 months in the up-front surgery group.

- In the intention-to-treat arm, 61% of patients who received neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy underwent resection, resulting in R0 resection for 41% of patients and node-negative disease for 65% of patients. The resection rate was 72% in the up-front surgery arm, resulting in R0 resection in 28% of patients and node-negative disease in 18% of patients.

The optimal neoadjuvant therapy regimen is unknown, and additional chemotherapy regimens are being evaluated in the following trials: ALLIANCE (NCT04340141), PREOPANC-3 (NCT04927780), PANACHE-01-PRODIGE (NCT02959879), and NorPACT-01 (NCT02919787).

Surgery

Complete resection can yield 5-year survival rates of 18% to 24%, but ultimate control remains poor because of the high incidence of both local and distant tumor recurrence. Thus, systemic therapy is also recommended.[14-16][Level of evidence C1]

Approximately 20% of patients present with pancreatic cancer amenable to local surgical resection, with operative mortality rates of approximately 1% to 16%.[17-21] Using information from the Medicare claims database, a national cohort study of more than 7,000 patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy between 1992 and 1995 revealed higher in-hospital mortality rates at low-volume hospitals (<1 pancreaticoduodenectomy per year) versus high-volume hospitals (>5 per year) (16% vs. 4%, respectively; P < .01).[17]

Postoperative chemotherapy

Historically, multiple randomized trials have established that adjuvant gemcitabine monotherapy [22] or adjuvant 5-FU monotherapy [3] improve OS for 6 months after surgical resection compared with surgery alone. More recent studies have looked at newer combination regimens that might further improve outcomes after surgical resection.

For patients with good performance status, adjuvant FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy or the combination of gemcitabine and capecitabine should be considered. However, for older patients or patients with marginal performance status, adjuvant gemcitabine or 5-FU monotherapy can be considered. In Asia, S-1 (tegafur, gimeracil, and oteracil potassium) is an appropriate alternative to gemcitabine-based therapies.

Evidence (postoperative chemotherapy):

- FOLFIRINOX: In the randomized, open-label, phase III PRODIGE-24 trial (NCT01526135), 493 patients with R0/R1 resections were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive six cycles of gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 on days 1, 8, and 15 of a 28-day cycle) or 12 cycles of FOLFIRINOX (oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2, leucovorin 400 mg/m2, irinotecan 150 mg/m2, and 5-FU 2,400 mg/m2 over 46 hours every 2 weeks).[23,24][Level of evidence A1]

- With a median follow-up of 69.7 months, the median disease-free survival (DFS) was 21.4 months (95% CI, 17.5–26.7) in the FOLFIRINOX group and 12.8 months in the gemcitabine group (95% CI, 11.6–15.2) (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.54–0.82; P < .001).

- The median OS was 53.5 months (95% CI, 43.5–58.4) in the FOLFIRINOX group and 35.5 months (95% CI, 30.1–40.3) in the gemcitabine group (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.54–0.85; P = .001). The 5-year OS rate was 43.2% in the FOLFIRINOX group and 31.4% in the gemcitabine group.

- Toxicity was higher with combination therapy; 75.9% of patients who received FOLFIRINOX had grade 3 or 4 toxicities, compared with 52.9% of those who received gemcitabine, with similar rates of neutropenia (although 62.2% of patients on FOLFIRINOX received granulocyte colony-stimulating factor). Thirty-three percent of patients who received FOLFIRINOX stopped treatment prematurely, compared with 21% of patients who received gemcitabine alone.

- Gemcitabine and capecitabine: The European Study for Pancreatic Cancer (ESPAC-4 [NCT00058201]) trial randomly assigned 732 patients with resected pancreatic cancer to receive either six cycles of gemcitabine alone (1,000 mg/m2 given weekly for 3 weeks of every 4 weeks) or oral capecitabine (1,660 mg/m2 given for 21 days followed by 7 days of rest [one cycle]).[25][Level of evidence A1]

- With a median follow-up of 43.2 months, the median OS for patients in the gemcitabine/capecitabine group was 28.0 months (95% CI, 23.5–31.5) compared with 25.5 months for the gemcitabine-alone group (95% CI, 22.7–27.9; HR, 0.82; P = .032). Treatment with gemcitabine/capecitabine yielded an improvement in the estimated 5-year OS rate from 16.3% with gemcitabine alone to 28.8% with gemcitabine/capecitabine.

- There was no significant difference in overall rates of grade 3/4 toxicities between treatment arms. Compared with gemcitabine alone, capecitabine was associated with higher rates of grade 3/4 diarrhea (5% vs. 2%), neutropenia (38% vs. 24%), and hand-foot syndrome (7% vs. 0%).

- There was no significant effect on the quality of life in the treatment groups.

- Based on these findings, the adjuvant combination of gemcitabine and capecitabine is the standard of care after a resection for pancreatic cancer.

- S-1: The Japan Adjuvant Study Group of Pancreatic Cancer (JASPAC-01) study was a phase III, multicenter, noninferiority trial conducted in Japan that randomly assigned 385 patients to receive either gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 weekly for 3 weeks of every 4 weeks) for six cycles or S-1 (tegafur, gimeracil, and oteracil potassium) (given orally twice a day for 4 weeks followed by a 2-week break).[26][Level of evidence A1]

- The prespecified criteria for early discontinuation was met at interim analysis for efficacy with all of the protocol treatments completed. On early interim analysis, the HRmortality was 0.57 (95% CI, 0.44–0.72; P for noninferiority < .001; P for superiority < .001). These results were associated with a 5-year OS rate of 24.4% in the gemcitabine group and 44.1% in the S-1 group.

- Grade 3 or 4 leukopenia, neutropenia, and liver transaminitis were observed more frequently in the gemcitabine group, and stomatitis and diarrhea were experienced more frequently in the S-1 group.

- Among Japanese patients, adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 can be a new standard of care for resected pancreatic patients. Additional studies are needed to validate these results in patients of other races and ethnicities.

- The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of S-1 may be different between Eastern and Western patient populations because grade 3/4 gastrointestinal toxicities, especially diarrhea, have been reported more commonly in the Western patient population. S-1 is not currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in the United States.

- Gemcitabine: Charité Onkologie (CONKO)-001 was a multicenter phase III trial of 368 patients with resected pancreatic cancer who were randomly assigned to receive six cycles of adjuvant gemcitabine versus observation.[22][Level of evidence B1] In contrast to the previous trials, the primary end point was DFS.

- With a median follow-up of 136 months, long-term follow-up of the CONKO-001 study demonstrated a significant improvement in OS that favors gemcitabine (median survival, 22.8 months vs. 20.2 months; HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.61–0.95, P = .01). Gemcitabine compared with observation alone yielded improved survival rates at 5 years of 20.7% for the gemcitabine arm versus 10.4% for the observation-alone arm, and the survival rates at 10 years were 12.2% for the gemcitabine arm versus 7.7% for the observation-alone arm.[27][Level of evidence A1]

- Gemcitabine or 5-FU: The ESPAC-3 trial (NCT00058201) randomly assigned 1,088 patients who had undergone complete macroscopic resection to either 6 months of 5-FU (425 mg/m2) and leucovorin (20 mg/m2) on days 1 to 5 every 28 days or 6 months of gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2) on days 1, 8, and 15 every 28 days.[3][Level of evidence A1]

- Median OS was 23.0 months (95% CI, 21.1–25.0) for patients treated with 5-FU plus leucovorin and 23.6 months (95% CI, 21.4–26.4) for those treated with gemcitabine (HR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.81–1.08; P = .39).

Postoperative chemoradiation therapy

The role of postoperative therapy (chemotherapy with or without chemoradiation therapy) in the management of this disease remains controversial because much of the randomized clinical trial data available are statistically underpowered and provide conflicting results.[4-8]

Evidence (postoperative chemoradiation therapy):

Several phase III trials examined the potential OS benefit of postoperative adjuvant 5-FU–based chemoradiation therapy:

- Gastrointestinal Study Group (GITSG): A small randomized trial conducted by the GITSG in 1985 compared surgery alone with surgery followed by chemoradiation.[4][Level of evidence A1];[5][Level of evidence B4]

- The investigators reported a significant but modest improvement in median-term and long-term survival over resection alone with postoperative bolus 5-FU and regional split-course radiation given at a dose of 40 Gy.

- European Organisation for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC): An attempt by the EORTC to reproduce the results of the GITSG trial failed to confirm a significant benefit for adjuvant chemoradiation therapy over resection alone;[6][Level of evidence A1] however, this trial treated patients with pancreatic and periampullary cancers (with a potentially better prognosis).

- A subset analysis of the patients with primary pancreatic tumors indicated a trend toward improved median, 2-year, and 5-year OS with adjuvant therapy (17.1 months, 37%, and 20%, respectively) compared with surgery alone (12.6 months, 23%, and 10%, respectively); P = .09 for median survival).

- An updated analysis of a subsequent ESPAC-1 trial examined only patients who underwent strict randomization after pancreatic resection. The patients were assigned to one of four groups (observation, bolus 5-FU chemotherapy, bolus 5-FU chemoradiation therapy, or chemoradiation therapy followed by additional chemotherapy).[7,8,28][Level of evidence A1]

- With a 2 × 2 factorial design reported at a median follow-up of 47 months, a median survival benefit was observed for only the patients who received postoperative 5-FU chemotherapy. However, these results were difficult to interpret because of a high rate of protocol nonadherence and the lack of a separate analysis for each of the four groups in the 2 × 2 design.

- U.S. Gastrointestinal Intergroup: The U.S. Gastrointestinal Intergroup has reported the results of a randomized phase III trial (Radiation Therapy Oncology Group [RTOG]-9704) that included 451 patients with resected pancreatic cancers who were assigned to receive either postoperative infusional 5-FU plus infusional 5-FU and concurrent radiation or adjuvant gemcitabine plus infusional 5-FU and concurrent radiation.[29][Level of evidence A1] The primary end points were OS for all patients and OS for patients with pancreatic head tumors.

- A 5-year update of RTOG-9704 reported that patients with pancreatic head tumors (n = 388) had a median survival of 20.5 months and a 5-year OS rate of 22% with gemcitabine, versus a median survival of 17.1 months and a 5-year OS rate of 18% with 5-FU (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.67–1.05; P = .12).[30]

- Univariate analysis showed no difference in OS. However, on multivariate analysis, patients on the gemcitabine arm with pancreatic head tumors experienced a trend toward improved OS (P = .08). Distant relapse remained the predominant site of first failure (78%).

The EORTC/U.S. Gastrointestinal Intergroup RTOG-0848 phase III adjuvant trial evaluating the impact of chemoradiation therapy after completion of a full course of gemcitabine with or without erlotinib has closed and results are pending.

Additional trials are still warranted to determine more effective systemic therapy for this disease.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Dalton RR, Sarr MG, van Heerden JA, et al.: Carcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas: is curative resection justified? Surgery 111 (5): 489-94, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Brennan MF, Moccia RD, Klimstra D: Management of adenocarcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas. Ann Surg 223 (5): 506-11; discussion 511-2, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Bassi C, et al.: Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid vs gemcitabine following pancreatic cancer resection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 304 (10): 1073-81, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Further evidence of effective adjuvant combined radiation and chemotherapy following curative resection of pancreatic cancer. Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group. Cancer 59 (12): 2006-10, 1987. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kalser MH, Ellenberg SS: Pancreatic cancer. Adjuvant combined radiation and chemotherapy following curative resection. Arch Surg 120 (8): 899-903, 1985. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Klinkenbijl JH, Jeekel J, Sahmoud T, et al.: Adjuvant radiotherapy and 5-fluorouracil after curative resection of cancer of the pancreas and periampullary region: phase III trial of the EORTC gastrointestinal tract cancer cooperative group. Ann Surg 230 (6): 776-82; discussion 782-4, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Neoptolemos JP, Dunn JA, Stocken DD, et al.: Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy in resectable pancreatic cancer: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 358 (9293): 1576-85, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, et al.: A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 350 (12): 1200-10, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Stessin AM, Meyer JE, Sherr DL: Neoadjuvant radiation is associated with improved survival in patients with resectable pancreatic cancer: an analysis of data from the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) registry. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 72 (4): 1128-33, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Versteijne E, Vogel JA, Besselink MG, et al.: Meta-analysis comparing upfront surgery with neoadjuvant treatment in patients with resectable or borderline resectable pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg 105 (8): 946-958, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mokdad AA, Minter RM, Zhu H, et al.: Neoadjuvant Therapy Followed by Resection Versus Upfront Resection for Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: A Propensity Score Matched Analysis. J Clin Oncol 35 (5): 515-522, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Katz MHG, Shi Q, Meyers J, et al.: Efficacy of Preoperative mFOLFIRINOX vs mFOLFIRINOX Plus Hypofractionated Radiotherapy for Borderline Resectable Adenocarcinoma of the Pancreas: The A021501 Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 8 (9): 1263-1270, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Versteijne E, van Dam JL, Suker M, et al.: Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy Versus Upfront Surgery for Resectable and Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer: Long-Term Results of the Dutch Randomized PREOPANC Trial. J Clin Oncol 40 (11): 1220-1230, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cameron JL, Crist DW, Sitzmann JV, et al.: Factors influencing survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. Am J Surg 161 (1): 120-4; discussion 124-5, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, et al.: Pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer of the head of the pancreas. 201 patients. Ann Surg 221 (6): 721-31; discussion 731-3, 1995. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Yeo CJ, Abrams RA, Grochow LB, et al.: Pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: postoperative adjuvant chemoradiation improves survival. A prospective, single-institution experience. Ann Surg 225 (5): 621-33; discussion 633-6, 1997. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Birkmeyer JD, Finlayson SR, Tosteson AN, et al.: Effect of hospital volume on in-hospital mortality with pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery 125 (3): 250-6, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cameron JL, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ, et al.: One hundred and forty-five consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies without mortality. Ann Surg 217 (5): 430-5; discussion 435-8, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Spanknebel K, Conlon KC: Advances in the surgical management of pancreatic cancer. Cancer J 7 (4): 312-23, 2001 Jul-Aug. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Balcom JH, Rattner DW, Warshaw AL, et al.: Ten-year experience with 733 pancreatic resections: changing indications, older patients, and decreasing length of hospitalization. Arch Surg 136 (4): 391-8, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, et al.: Resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas-616 patients: results, outcomes, and prognostic indicators. J Gastrointest Surg 4 (6): 567-79, 2000 Nov-Dec. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, et al.: Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 297 (3): 267-77, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Conroy T, Hammel P, Hebbar M, et al.: FOLFIRINOX or Gemcitabine as Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. N Engl J Med 379 (25): 2395-2406, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Conroy T, Castan F, Lopez A, et al.: Five-Year Outcomes of FOLFIRINOX vs Gemcitabine as Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 8 (11): 1571-1578, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Neoptolemos JP, Palmer DH, Ghaneh P, et al.: Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 389 (10073): 1011-1024, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Uesaka K, Boku N, Fukutomi A, et al.: Adjuvant chemotherapy of S-1 versus gemcitabine for resected pancreatic cancer: a phase 3, open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial (JASPAC 01). Lancet 388 (10041): 248-57, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Oettle H, Neuhaus P, Hochhaus A, et al.: Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and long-term outcomes among patients with resected pancreatic cancer: the CONKO-001 randomized trial. JAMA 310 (14): 1473-81, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Choti MA: Adjuvant therapy for pancreatic cancer--the debate continues. N Engl J Med 350 (12): 1249-51, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Regine WF, Winter KA, Abrams RA, et al.: Fluorouracil vs gemcitabine chemotherapy before and after fluorouracil-based chemoradiation following resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 299 (9): 1019-26, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Regine WF, Winter KA, Abrams R, et al.: Fluorouracil-based chemoradiation with either gemcitabine or fluorouracil chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: 5-year analysis of the U.S. Intergroup/RTOG 9704 phase III trial. Ann Surg Oncol 18 (5): 1319-26, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer

Treatment Options for Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer

While locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer are both incurable, their natural histories may be different. An autopsy series demonstrated that 30% of patients presenting with locally advanced disease died without evidence of distant metastases.[1][Level of evidence A1] Therefore, investigators have struggled to determine whether chemoradiation therapy for patients presenting with locally advanced disease is warranted.

Treatment options for locally advanced pancreatic cancer include:

- Chemotherapy with or without targeted therapy.

- Chemoradiation therapy: Chemotherapy followed by chemoradiation for patients without metastatic disease.

- Surgery: Radical pancreatic resection.

- Palliative surgery: Palliative surgical biliary and/or gastric bypass, percutaneous radiologic biliary stent placement, or endoscopic biliary stent placement.[2,3]

- Clinical trials evaluating novel agents in combination with chemotherapy or chemoradiation therapy for patients with unresectable tumors.

- Intraoperative radiation therapy and/or implantation of radioactive sources (under clinical evaluation).[4,5]

Palliative therapies can be considered in patients with any stage of disease. For more information, see the Palliative Therapy section.

Chemotherapy with or without targeted therapy

Chemotherapy is the primary treatment modality for patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancers and uses the same regimens as those used to treat patients with metastatic disease.

Evidence (chemotherapy):

- FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine: A multicenter phase II/III trial included 342 patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score of 0 or 1.[6][Level of evidence A1] The patients were randomly assigned to receive FOLFIRINOX (oxaliplatin [85 mg/m2], irinotecan [180 mg/m2], leucovorin [400 mg/m2], and fluorouracil [5-FU; 400 mg/m2] given as a bolus followed by 2,400 mg/m2 given as a 46-hour continuous infusion, every 2 weeks) or gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 weekly for 7 of 8 weeks and then weekly for 3 of 4 weeks).

- The median overall survival (OS) was 11.1 months in the FOLFIRINOX group compared with 6.8 months in the gemcitabine group (hazard ratio [HR]death, 0.57; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.45–0.73; P < .001).

- Median progression-free survival (PFS) was 6.4 months in the FOLFIRINOX group and 3.3 months in the gemcitabine group (HRdisease progression, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.37–0.59; P < .001).

- FOLFIRINOX was more toxic than gemcitabine; 5.4% of patients in this group had febrile neutropenia. At 6 months, 31% of the patients in the FOLFIRINOX group had a definitive degradation of quality of life, versus 66% in the gemcitabine group (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.30–0.70; P < .001).

- Based on this trial, FOLFIRINOX is considered a standard treatment option for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

- Gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel versus gemcitabine: A multicenter, international, phase III trial (NCT00844649) included 861 patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Patients had a Karnofsky Performance Status of at least 70 and had not previously received chemotherapy for metastatic disease.[7][Level of evidence A1] Patients who received adjuvant gemcitabine or any other chemotherapy were excluded. The patients were randomly assigned to receive gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2) and nab-paclitaxel (125 mg/m2 of body-surface area) weekly for 3 of 4 weeks or gemcitabine monotherapy (1,000 mg/m2 weekly for 7 of 8 weeks and then weekly for 3 of 4 weeks).

- The median OS was 8.5 months in the nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine group compared with 6.7 months in the gemcitabine group (HRdeath, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.62–0.83; P < .001).

- Median PFS was 5.5 months in the nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine group and 3.7 months in the gemcitabine group (HRdisease progression, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.58–0.82; P < .001).

- Nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine was more toxic than gemcitabine. The most common grade 3 toxicities in the nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine group were neutropenia (38%), fatigue (17%), and neuropathy (17%); febrile neutropenia occurred in 3% of patients. In the gemcitabine-alone group, the most common grade 3 toxicities were neutropenia (27%), fatigue (1%), and neuropathy (1%); febrile neutropenia occurred in 1% of patients.

- In the nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine group, the median time from grade 3 neuropathy to grade 1 or resolution was 29 days. Of patients with grade 3 peripheral neuropathy, 44% were able to resume treatment at a reduced dose within a median of 23 days after onset of a grade 3 event.

- Based on this trial, nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine is a standard treatment option for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

- Quality-of-life data were not measured for this regimen, and this study did not address the efficacy of nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine versus FOLFIRINOX.

- Gemcitabine versus 5-FU: Gemcitabine has demonstrated activity in patients with pancreatic cancer and is a useful palliative agent.[8-10] A phase III trial of gemcitabine versus 5-FU as first-line therapy in patients with advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas reported a significant improvement in survival among patients treated with gemcitabine (the 1-year survival rate was 18% with gemcitabine compared with 2% with 5-FU; P = .003).[9][Level of evidence A1]

- Gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine and erlotinib: The National Cancer Institute of Canada performed a phase III trial (CAN-NCIC-PA3 [NCT00026338]) that compared gemcitabine alone with the combination of gemcitabine and erlotinib (100 mg/d) in patients with advanced or metastatic pancreatic carcinomas.[11][Level of evidence A1]

- The addition of erlotinib modestly prolonged survival when combined with gemcitabine versus gemcitabine alone (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.69–0.99; P = .038).

- The median and 1-year survival rates for patients who received erlotinib were 6.2 months and 23%. The median and 1-year survival rates for patients who received placebo were 5.9 months and 17%.

- Platinum analogue or fluoropyrimidine versus single-agent gemcitabine: Many phase III studies have evaluated a combination regimen with either a platinum analogue (cisplatin or oxaliplatin) or fluoropyrimidine versus single-agent gemcitabine.[12,13]

- None of these phase III trials have demonstrated a statistically significant advantage favoring the use of combination chemotherapy in the first-line treatment of metastatic pancreatic cancer.

- 5-FU, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (OFF regimen) versus best supportive care (BSC): Second-line chemotherapy after progression on a gemcitabine-based regimen may be beneficial. The Charité Onkologie (CONKO)-003 investigators randomly assigned patients requiring a second line of chemotherapy to either the OFF regimen or BSC.[14,15][Level of evidence C1] The OFF regimen consisted of leucovorin (200 mg/m2) followed by 5-FU (2,000 mg/m2 [24-hour continuous infusion] on days 1, 8, 15, and 22) and oxaliplatin (85 mg/m2 on days 8 and 22). After a rest of 3 weeks, the next cycle was started on day 43. The trial was terminated early because of poor accrual, and only 46 patients were randomly assigned to either the OFF regimen or BSC.

- The median survival was 4.82 months (95% CI, 4.29–5.35) with the OFF treatment regimen and 2.30 months (95% CI, 1.76–2.83) with BSC alone (HR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.24–0.83).

- Median OS was 9.09 months for the sequence of gemcitabine/OFF and 7.90 months for gemcitabine/BSC.

- The early closure of the study and the very small number of patients made the P values misleading. Therefore, second-line chemotherapy with the OFF regimen may be falsely associated with improved survival.

Chemoradiation therapy

The role of chemoradiation in locally advanced pancreatic cancer remains controversial. Table 7 summarizes phase III randomized studies of chemoradiation for locally advanced pancreatic cancer.

| Trial | Regimen | Chemoradiation | Radiation Alone | Chemotherapy Alone | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-FU = fluorouracil; ECOG = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FFCD = Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive; GEM = gemcitabine; GITSG = Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group; Gy = gray (unit of absorbed radiation of ionizing radiation); P value = probability value; XRT = radiation therapy. | |||||

| Pre-2000 | |||||

| GITSG [16] | Radiation alone vs. 5-FU/60 Gy XRT | 40 wk | 20 wk | <.01 | |

| ECOG [17] | Radiation vs. 5-FU, mitomycin C/59 Gy XRT | 8.4 mo | 7.1 mo | .16 | |

| Post-2000 | |||||

| FFCD [18] | GEM vs. GEM, cisplatin, 60 Gy XRT | 8.6 mo | 13 mo | .03 | |

| ECOG [19] | GEM vs. GEM/50.4 Gy XRT | 11.1 mo | 9.2 mo | .017 | |

Evidence (chemoradiation therapy):

Three trials evaluated combined modality therapy versus radiation therapy alone.[16-18] The trials had substantial deficiencies in design or analysis. Initially, the standard of practice was to give chemoradiation therapy based on data from the first two studies. However, with the publication of the third study, standard practice changed to chemotherapy followed by chemoradiation in the absence of metastases.

- LAP07 (NCT00634725): The LAP07 study was an international, randomized, phase III study based on the results of the Groupe Coopérateur Multidisciplinaire en Oncologie (GERCOR) study. In total, 449 patients were enrolled between 2008 and 2011, with random assignment via a two-step randomization process. In the first step, patients were randomly assigned to induction gemcitabine (n = 223) or gemcitabine plus erlotinib (n = 219) for four cycles. For the second step, patients with controlled tumors were randomly assigned (n = 269) a second time to receive either chemotherapy (n = 136) or chemoradiation therapy (n = 133). A total dose of 54 Gy in 30 daily fractions was prescribed with concurrent capecitabine at a dose of 800 mg/m2 twice daily on days of radiation therapy.[20][Level of evidence A1]

- The primary end point was OS. After interim analysis, the study was stopped early because of futility.

- With a median follow-up of 36.7 months, the median OS from the date of the first randomization was not significantly different between chemotherapy at 16.5 months (95% CI, 14.5–18.5) and chemoradiation therapy at 15.2 months (95% CI, 13.9–17.3; P = .83).

- Median OS after the first randomization was 13.6 months (95% CI, 12.3–15.3) for the patients who received gemcitabine and was 11.9 months (95% CI, 10.4–13.5; P = .09) for the patients who received gemcitabine plus erlotinib.

The LAP07 study represents the most robust, prospective, randomized phase III data regarding the role of chemoradiation therapy in the setting of gemcitabine-based induction chemotherapy that demonstrates no OS benefit. However, this study was initiated before the advent of FOLFIRINOX chemotherapy, which has been widely adopted into the locally advanced setting. The role of chemoradiation in the setting of more active chemotherapy regimens, including gemcitabine/paclitaxel and FOLFIRINOX, has yet to be evaluated.

- Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group (GITSG) GITSG-9273 trial: Before 2000, several phase III trials evaluated combined modality therapy versus radiation therapy alone. Before the use of gemcitabine for patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer, investigators from the GITSG randomly assigned 106 patients with locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma to receive external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) (60 Gy) alone or concurrent EBRT (either 40 Gy or 60 Gy) plus bolus 5-FU.[16][Level of evidence A1]

- The study was stopped early when the chemoradiation therapy groups were found to have better efficacy. The 1-year survival rate was 11% for patients who received EBRT alone compared with 38% for patients who received chemoradiation therapy with 40 Gy and 36% for patients who received chemoradiation therapy with 60 Gy.

- After an additional 88 patients were enrolled in the combined modality arms, there was a trend toward improved survival with 60 Gy EBRT plus 5-FU, but the difference in time-to-progression and OS was not statistically significant when compared with the 40 Gy arm.[21]

- ECOG E-8282 trial: Investigators from the ECOG randomly assigned 114 patients to receive radiation therapy (59.4 Gy) alone or with concurrent infusional 5-FU (1,000 mg/m2/d on days 2–5 and 28–31) plus mitomycin (10 mg/m2 on day 2).[17]

- The trial reported no difference in OS between the two groups.

- Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive–Société Française de Radiothérapie Oncologie (FFCD-SFRO) trial: As it became clear that radiation therapy alone was an inadequate treatment, investigators evaluated combined modality approaches versus chemotherapy alone. Investigators from the FFCD-SFRO randomly assigned 119 patients to induction chemoradiation therapy (60 Gy in 2 Gy fractions with 300 mg/m2/d of continuous-infusion 5-FU on days 1–5 for 6 weeks and 20 mg/m2/d of cisplatin on days 1–5 during weeks 1 and 5) or induction gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 weekly for 7 weeks). Maintenance gemcitabine was administered to both groups until stopped by disease progression or treatment discontinuation as a result of toxicity.[22][Level of evidence A1]

- Median survival was superior in the gemcitabine group (13 vs. 8.6 months; P = .03).

- Nonhematological grade 3 to 4 toxicities (primarily gastrointestinal) were significantly more common in the chemoradiation therapy group (44% vs. 18%; P = .004), and fewer patients completed at least 75% of induction therapy (42% vs. 73%).

- Nonetheless, the survival benefit persisted in a per-protocol analysis of patients receiving at least 75% of planned therapy. Notably, the dose intensity of maintenance gemcitabine was significantly less in the chemoradiation therapy group because of a greater incidence of grades 3 to 4 hematological toxicities (71% vs. 27%; P = .0001).

- As a result of this study, giving induction chemoradiation therapy has lost support.

- ECOG: The results of the FFCD-SFRO study counter the results of a study from ECOG in which investigators randomly assigned 74 patients to either gemcitabine alone or gemcitabine with radiation followed by gemcitabine.[19] Of note, the study was closed early as the result of poor accrual.

- The primary end point was survival, which was 9.2 months (95% CI, 7.9–11.4) for chemotherapy and 11.1 months (95% CI, 7.6–15.5) for combined modality therapy (one-sided P = .017 by stratified log-rank test).

- Grades 4 and 5 toxicity were greater in the chemoradiation therapy arm than in the chemotherapy arm (41% vs. 9%).

- GERCOR: Given the increased toxicity of chemoradiation therapy and the early development of metastatic disease in a large percentage of patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer, investigators are pursuing a strategy of selecting patients with localized disease for chemoradiation therapy. With this strategy, the selected patients have an absence of progressive disease locally or systemically after several months of chemotherapy.[23][Level of evidence C1]

- A retrospective analysis of 181 patients enrolled in prospective phase II and III GERCOR studies revealed that 29% had metastatic disease after 3 months of gemcitabine-based chemotherapy.

- For the remaining 71%, median OS was significantly longer among patients treated with chemoradiation therapy than among patients treated with additional chemotherapy (15.0 months vs. 11.7 months; P = .0009).

Surgery

Patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer have tumors that are technically unresectable because of local vessel impingement or invasion by tumor. However, with the combination of chemotherapy and chemoradiation therapy, some patients may become candidates for radical pancreatic resection.

Palliative surgery

A significant proportion (approximately one-third) of patients with pancreatic cancer present with locally advanced disease. Patients may benefit from palliation of biliary obstruction by endoscopic, surgical, or radiological means.[24]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Fu B, Yachida S, et al.: DPC4 gene status of the primary carcinoma correlates with patterns of failure in patients with pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 27 (11): 1806-13, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- van den Bosch RP, van der Schelling GP, Klinkenbijl JH, et al.: Guidelines for the application of surgery and endoprostheses in the palliation of obstructive jaundice in advanced cancer of the pancreas. Ann Surg 219 (1): 18-24, 1994. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Baron TH: Expandable metal stents for the treatment of cancerous obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract. N Engl J Med 344 (22): 1681-7, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tepper JE, Noyes D, Krall JM, et al.: Intraoperative radiation therapy of pancreatic carcinoma: a report of RTOG-8505. Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 21 (5): 1145-9, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Reni M, Panucci MG, Ferreri AJ, et al.: Effect on local control and survival of electron beam intraoperative irradiation for resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 50 (3): 651-8, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al.: FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 364 (19): 1817-25, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, et al.: Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med 369 (18): 1691-703, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rothenberg ML, Moore MJ, Cripps MC, et al.: A phase II trial of gemcitabine in patients with 5-FU-refractory pancreas cancer. Ann Oncol 7 (4): 347-53, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Burris HA, Moore MJ, Andersen J, et al.: Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 15 (6): 2403-13, 1997. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Storniolo AM, Enas NH, Brown CA, et al.: An investigational new drug treatment program for patients with gemcitabine: results for over 3000 patients with pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer 85 (6): 1261-8, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, et al.: Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol 25 (15): 1960-6, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Poplin E, Feng Y, Berlin J, et al.: Phase III, randomized study of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin versus gemcitabine (fixed-dose rate infusion) compared with gemcitabine (30-minute infusion) in patients with pancreatic carcinoma E6201: a trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 27 (23): 3778-85, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Colucci G, Labianca R, Di Costanzo F, et al.: Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with single-agent gemcitabine as first-line treatment of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: the GIP-1 study. J Clin Oncol 28 (10): 1645-51, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Pelzer U, Kubica K, Stieler J, et al.: A randomized trial in patients with gemcitabine refractory pancreatic cancer. Final results of the CONKO 003 study. [Abstract] J Clin Oncol 26 (Suppl 15): A-4508, 2008.

- Pelzer U, Schwaner I, Stieler J, et al.: Best supportive care (BSC) versus oxaliplatin, folinic acid and 5-fluorouracil (OFF) plus BSC in patients for second-line advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III-study from the German CONKO-study group. Eur J Cancer 47 (11): 1676-81, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- A multi-institutional comparative trial of radiation therapy alone and in combination with 5-fluorouracil for locally unresectable pancreatic carcinoma. The Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group. Ann Surg 189 (2): 205-8, 1979. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cohen SJ, Dobelbower R, Lipsitz S, et al.: A randomized phase III study of radiotherapy alone or with 5-fluorouracil and mitomycin-C in patients with locally advanced adenocarcinoma of the pancreas: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group study E8282. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 62 (5): 1345-50, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Chauffert B, Mornex F, Bonnetain F, et al.: Phase III trial comparing initial chemoradiotherapy (intermittent cisplatin and infusional 5-FU) followed by gemcitabine vs. gemcitabine alone in patients with locally advanced non metastatic pancreatic cancer: a FFCD-SFRO study. [Abstract] J Clin Oncol 24 (Suppl 18): A-4008, 180s, 2006.

- Loehrer PJ, Feng Y, Cardenes H, et al.: Gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine plus radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced pancreatic cancer: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol 29 (31): 4105-12, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hammel P, Huguet F, van Laethem JL, et al.: Effect of Chemoradiotherapy vs Chemotherapy on Survival in Patients With Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer Controlled After 4 Months of Gemcitabine With or Without Erlotinib: The LAP07 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 315 (17): 1844-53, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Moertel CG, Frytak S, Hahn RG, et al.: Therapy of locally unresectable pancreatic carcinoma: a randomized comparison of high dose (6000 rads) radiation alone, moderate dose radiation (4000 rads + 5-fluorouracil), and high dose radiation + 5-fluorouracil: The Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group. Cancer 48 (8): 1705-10, 1981. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Chauffert B, Mornex F, Bonnetain F, et al.: Phase III trial comparing intensive induction chemoradiotherapy (60 Gy, infusional 5-FU and intermittent cisplatin) followed by maintenance gemcitabine with gemcitabine alone for locally advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer. Definitive results of the 2000-01 FFCD/SFRO study. Ann Oncol 19 (9): 1592-9, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Huguet F, André T, Hammel P, et al.: Impact of chemoradiotherapy after disease control with chemotherapy in locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma in GERCOR phase II and III studies. J Clin Oncol 25 (3): 326-31, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sohn TA, Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, et al.: Surgical palliation of unresectable periampullary adenocarcinoma in the 1990s. J Am Coll Surg 188 (6): 658-66; discussion 666-9, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Metastatic or Recurrent Pancreatic Cancer

Treatment Options for Metastatic or Recurrent Pancreatic Cancer

Treatment options for metastatic or recurrent pancreatic cancer include:

- Chemotherapy with or without targeted therapy.

- Clinical trials evaluating new anticancer agents alone or in combination with chemotherapy.

Palliative therapies can be considered in patients with any stage of disease. For more information, see the Palliative Therapy section.

Chemotherapy with or without targeted therapy

Because of the low objective response rate and limited efficacy of palliative chemotherapy regimens, all newly diagnosed patients should consider enrolling in clinical trials. Multiagent chemotherapy combinations have been shown to prolong outcomes compared with single-agent gemcitabine.[1-3]

Evidence (single-agent chemotherapy):

- Gemcitabine versus fluorouracil (5-FU): A phase III trial of gemcitabine versus 5-FU as first-line therapy in patients with advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas reported a significant improvement in survival among patients treated with gemcitabine (the 1-year survival rate was 18% with gemcitabine vs. 2% with 5-FU; P = .003).[1][Level of evidence A1]

Evidence (multiagent chemotherapy):

- FOLFIRINOX (leucovorin, 5-FU, irinotecan, and oxaliplatin) versus gemcitabine: A multicenter phase II/III trial included 342 patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status score of 0 or 1.[4][Level of evidence A1] The patients were randomly assigned to receive FOLFIRINOX (oxaliplatin [85 mg/m2], irinotecan [180 mg/m2], leucovorin [400 mg/m2], and 5-FU [400 mg/m2] given as a bolus followed by 2,400 mg/m2 given as a 46-hour continuous infusion, every 2 weeks) or gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 weekly for 7 of 8 weeks and then weekly for 3 of 4 weeks).

- The median overall survival (OS) was 11.1 months in the FOLFIRINOX group compared with 6.8 months in the gemcitabine group (hazard ratio [HR]death, 0.57; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.45–0.73; P < .001).

- Median progression-free survival (PFS) was 6.4 months in the FOLFIRINOX group and 3.3 months in the gemcitabine group (HR for disease progression, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.37–0.59; P < .001).

- FOLFIRINOX was more toxic than gemcitabine; 5.4% of patients in this group had febrile neutropenia. At 6 months, 31% of the patients in the FOLFIRINOX group had a definitive degradation of quality of life versus 66% in the gemcitabine group (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.30–0.70; P < .001).

- Based on this trial, FOLFIRINOX is considered a standard treatment option for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

- NALIRIFOX (5-FU, irinotecan sucrosofate [also called nanoliposomal irinotecan], and oxaliplatin) versus gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel: The multicenter, open-label, phase III NAPOLI 3 study (NCT04083235) included 770 patients with confirmed pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma who had not been treated previously for metastatic disease. The patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive NALIRIFOX (irinotecan sucrosofate [50 mg/m2], oxaliplatin [60 mg/m2], leucovorin [400 mg/m2], and 5-FU [2,400 mg/m2] as an intravenous infusion over 46 hours on days 1 and 15 of cycles lasting 28 days) or nab-paclitaxel (125 mg/m2) and gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2 given intravenously on days 1, 8, and 15 of cycles lasting 28 days). The primary end point was OS from randomization to death due to any cause, for NALIRIFOX versus gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel. Secondary end points included PFS and overall response rate by RECIST version 1.1.[5]

- The median OS was 11.1 months (95% CI, 10.0–12.1) in the NALIRIFOX group and 9.2 months (95% CI, 8.3–10.6) in the nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine group (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.7–0.99; P = .036). The median follow-up was 16.1 months.[5][Level of evidence A1]

- The median PFS was 7.4 months in the NALIRIFOX group and 5.6 months in the nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine group (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.58–0.83; P < .0001).

- The overall response rate was 42% in the NALIRIFOX group and 36% in the nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine group (P = .11). The median duration of response was 7.3 months in the NALIRIFOX group and 5 months in the nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine group (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.48–0.93).

- There were 369 patients (>99%) with any adverse event in the NALIRIFOX group and 376 patients (99%) with any adverse event in the nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine group. The most common grade 3 to 4 toxicities in the NALIRIFOX group were diarrhea (20%), hypokalemia (15%), neutropenia (14%), and nausea (12%). The most common grade 3 to 4 toxicities in the nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine group were neutropenia (25%) and anemia (17%). Of note, hematological toxicities (i.e., neutropenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia) were lower in the NALIRIFOX group than the nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine group. Peripheral neuropathy was noted in 3% of patients in the NALIRIFOX group compared with 6% of patients in the gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel group.

Based on this trial, NALIRIFOX is a standard first-line treatment option for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

- Gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel versus gemcitabine: A multicenter, international, phase III trial (NCT00844649) included 861 patients with metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Patients had a Karnofsky Performance Status of at least 70 and had not previously received chemotherapy for metastatic disease.[6][Level of evidence A1] Patients who received adjuvant gemcitabine or any other chemotherapy were excluded. The patients were randomly assigned to receive gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2) and nab-paclitaxel (125 mg/m2 of body-surface area) weekly for 3 of 4 weeks or gemcitabine monotherapy (1,000 mg/m2 weekly for 7 of 8 weeks and then weekly for 3 of 4 weeks).

- The median OS was 8.5 months in the nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine group compared with 6.7 months in the gemcitabine group (HRdeath, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.62–0.83; P < .001).

- Median PFS was 5.5 months in the nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine group and 3.7 months in the gemcitabine group (HRdisease progression, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.58–0.82; P < .001).

- Nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine was more toxic than gemcitabine. The most common grade 3 toxicities in the nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine group were neutropenia (38%), fatigue (17%), and neuropathy (17%); febrile neutropenia occurred in 3% of patients. In the gemcitabine-alone group, the most common grade 3 toxicities were neutropenia (27%), fatigue (1%), and neuropathy (1%); febrile neutropenia occurred in 1% of patients.

- In the nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine group, the median time from grade 3 neuropathy to grade 1 neuropathy or resolution was 29 days. Of patients with grade 3 peripheral neuropathy, 44% were able to resume treatment at a reduced dose within a median of 23 days after onset of a grade 3 event.

- Based on this trial, nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine is a standard treatment option for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

- Quality-of-life data were not measured for this regimen, and this study did not address the efficacy of nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine versus FOLFIRINOX.

- Gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine and erlotinib: The National Cancer Institute of Canada performed a phase III trial (CAN-NCIC-PA3 [NCT00026338]) that compared gemcitabine alone with the combination of gemcitabine and erlotinib (100 mg/d) in patients with advanced or metastatic pancreatic carcinomas.[7][Level of evidence A1]

- The addition of erlotinib modestly prolonged survival when combined with gemcitabine alone (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.69–0.99; P = .038).

- The corresponding median survival rate for patients receiving erlotinib was 6.2 months versus 5.9 months for patients receiving placebo. The 1-year survival rate for patients receiving erlotinib was 23% versus 17% for patients receiving placebo.

Evidence (second-line chemotherapy):

- Irinotecan sucrosofate with or without 5-FU and leucovorin: The NAPOLI-1 trial (NCT01494506) evaluated the role of irinotecan sucrosofate in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer who were previously treated with gemcitabine-based therapies.[8] Irinotecan sucrosofate is an encapsulated formulation of irinotecan designed to increase intratumoral levels of irinotecan and its active metabolite. In this study, a total of 417 patients were randomly assigned to receive either irinotecan sucrosofate monotherapy (120 mg/m2 every 3 weeks; n = 151), 5-FU and leucovorin (n = 149), or irinotecan sucrosofate (80 mg/m2 every 2 weeks plus 5-FU) and leucovorin (n = 117).[8][Level of evidence B1]

- Median OS was 6.1 months (95% CI, 4.8–8.9) in patients who received irinotecan sucrosofate with 5-FU and 4.2 months (95% CI, 3.6–4.9) in patients who received 5-FU and leucovorin (P = .012). Median OS was 4.9 months (95% CI, 4.2–5.6) for patients who received irinotecan sucrosofate monotherapy, compared with 4.2 months (95% CI, 3.6–4.9) for those who received 5-FU and leucovorin (unstratified HR, 0.99; P = .94). On multivariate analysis, irinotecan sucrosofate plus 5-FU and leucovorin was associated with improved OS (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.42–0.81).

- Grade 3 or 4 adverse events occurred most frequently in the patients who received irinotecan sucrosofate plus 5-FU and leucovorin and included neutropenia (27%), diarrhea (13%), vomiting (11%), and fatigue (14%).

- Despite differences in survival and toxicity between regimens, quality of life was not significantly different between treatment groups.

- The benefit of using irinotecan sucrosofate rather than unencapsulated irinotecan has not been established because the regimen for the control arm of this study was 5-FU/leucovorin. Additionally, the value of using irinotecan sucrosofate after FOLFIRINOX in the first-line setting is not clear.

- 5-FU, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin (OFF regimen) versus best supportive care (BSC): Second-line chemotherapy after progression on a gemcitabine-based regimen may be beneficial. The Charité Onkologie (CONKO)-003 investigators randomly assigned patients requiring a second line of chemotherapy to either an OFF regimen or BSC.[2]; [3][Level of evidence C1] The OFF regimen consisted of leucovorin (200 mg/m2) followed by 5-FU (2,000 mg/m2 [24 hours continuous infusion] on days 1, 8, 15, and 22) and oxaliplatin (85 mg/m2 on days 8 and 22). After a rest of 3 weeks, the next cycle was started on day 43. The trial was terminated early because of poor accrual, and only 46 patients were randomly assigned to either the OFF regimen or BSC.