Ovarian Borderline Tumors Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version

General Information About Ovarian Borderline Tumors

Incidence and Mortality

Ovarian borderline tumors (i.e., tumors of low malignant potential) account for 15% of all epithelial ovarian cancers. Nearly 75% of borderline tumors are stage I at the time of diagnosis.[1] Recognizing these tumors is important because their prognosis and treatment is different from the frankly malignant invasive carcinomas. Ovarian borderline tumors can also become low-grade serous tumors. For more information, see the Treatment of Low-Grade Serous Carcinoma section in Ovarian Epithelial, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer Treatment.

A review of 22 series (which included 953 patients), with a mean follow-up of 7 years, revealed a survival rate of 92% for patients with advanced-stage ovarian borderline tumors, if patients with so-called invasive implants were excluded. The causes of death in these patients were determined to be benign complications of disease (e.g., small bowel obstruction), complications of therapy, and only rarely (0.7% of patients), malignant transformation.[2] In one series, the 5-, 10-, 15-, and 20-year survival rates of patients with borderline tumors (all stages), as demonstrated by clinical life table analysis, were 97%, 95%, 92%, and 89%, respectively.[3] In this series, mortality rates were stage dependent: 0.7% of patients with stage I tumors, 4.2% of patients with stage II tumors, and 26.8% of patients with stage III tumors died of disease.[3] The Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique reported an extremely good prognosis for ovarian borderline tumors, with a 10-year survival rate of approximately 95%.[1] These survival rates are clearly in contrast with the 30% survival rate for patients with invasive tumors (all stages).

Another large retrospective study showed that early stage, serous histology, and younger age were associated with more favorable prognoses in patients with ovarian borderline tumors.[4]

Endometrioid Tumors

Endometrioid borderline tumors are less common and should not be regarded as malignant because they seldom, if ever, metastasize. However, malignant transformation can occur and may be associated with a similar tumor outside of the ovary. Such tumors are the result of either a second primary or rupture of the primary endometrial tumor.[5]

References

- Berek JS, Renz M, Kehoe S, et al.: Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum: 2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 155 (Suppl 1): 61-85, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kurman RJ, Trimble CL: The behavior of serous tumors of low malignant potential: are they ever malignant? Int J Gynecol Pathol 12 (2): 120-7, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Leake JF, Currie JL, Rosenshein NB, et al.: Long-term follow-up of serous ovarian tumors of low malignant potential. Gynecol Oncol 47 (2): 150-8, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kaern J, Tropé CG, Abeler VM: A retrospective study of 370 borderline tumors of the ovary treated at the Norwegian Radium Hospital from 1970 to 1982. A review of clinicopathologic features and treatment modalities. Cancer 71 (5): 1810-20, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Norris HJ: Proliferative endometrioid tumors and endometrioid tumors of low malignant potential of the ovary. Int J Gynecol Pathol 12 (2): 134-40, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

Stage Information for Ovarian Borderline Tumors

Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique (FIGO) Staging

FIGO and the American Joint Committee on Cancer have designated staging to define ovarian borderline tumors; the FIGO system is most commonly used.[1,2]

| Stage | Definition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique. | ||

| aAdapted from FIGO Committee for Gynecologic Oncology.[1] | ||

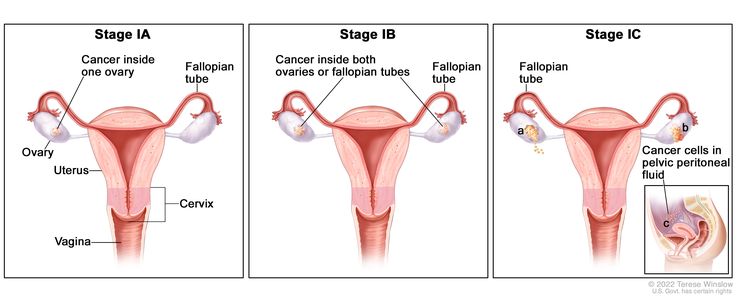

| I | Tumor confined to ovaries or fallopian tube(s). |

|

| IA | Tumor limited to one ovary (capsule intact) or fallopian tube; no tumor on ovarian or fallopian tube surface; no malignant cells in the ascites or peritoneal washings. | |

| IB | Tumor limited to both ovaries (capsules intact) or fallopian tubes; no tumor on ovarian or fallopian tube surface; no malignant cells in the ascites or peritoneal washings. | |

| IC | Tumor limited to one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes, with any of the following: | |

| IC1: Surgical spill. | ||

| IC2: Capsule ruptured before surgery or tumor on ovarian or fallopian tube surface. | ||

| IC3: Malignant cells in the ascites or peritoneal washings. | ||

| Stage | Definition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique. | ||

| aAdapted from FIGO Committee for Gynecologic Oncology.[1] | ||

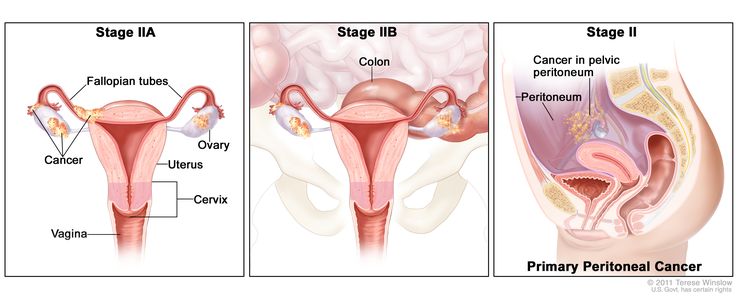

| II | Tumor involves one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes with pelvic extension (below the pelvic brim) or primary peritoneal cancer. |

|

| IIA | Extension and/or implants on uterus and/or fallopian tubes and/or ovaries. | |

| IIB | Extension to other pelvic intraperitoneal tissues. | |

| Stage | Definition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique. | ||

| aAdapted from FIGO Committee for Gynecologic Oncology.[1] | ||

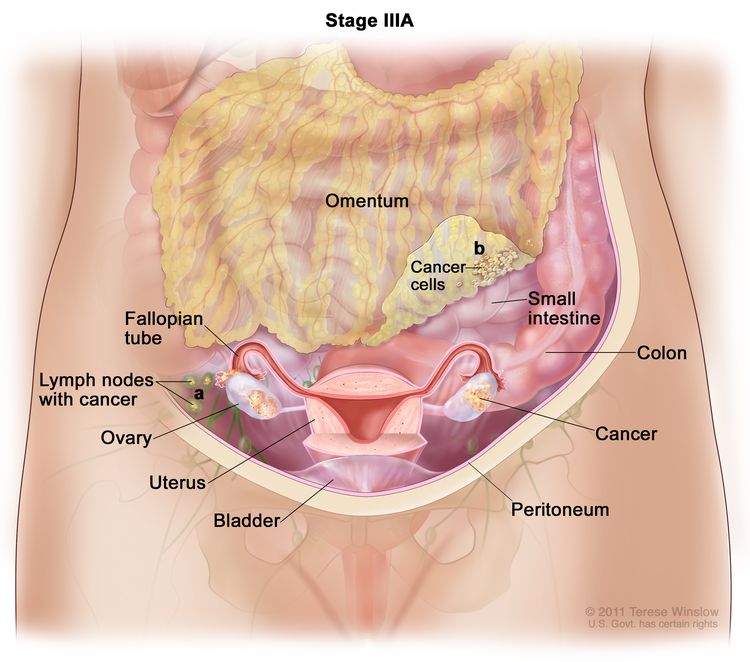

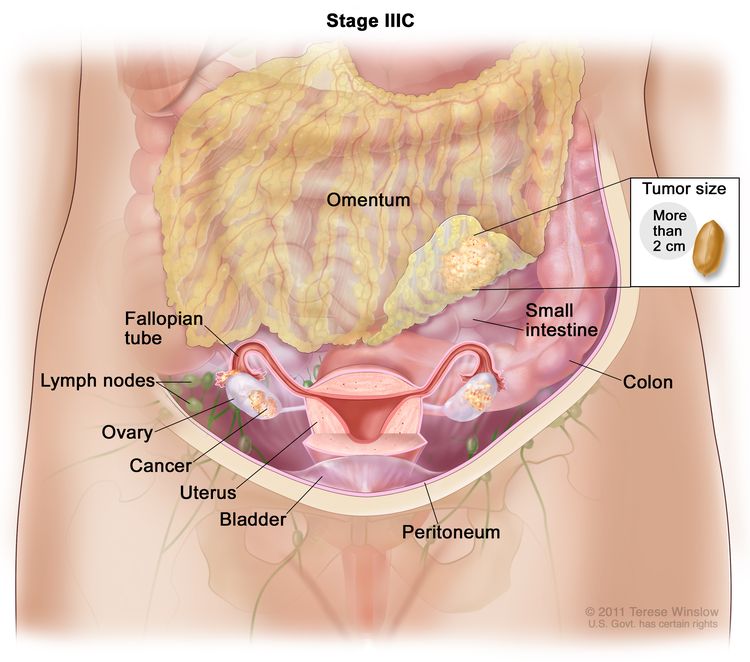

| III | Tumor involves one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes, or primary peritoneal cancer, with cytologically or histologically confirmed spread to the peritoneum outside the pelvis and/or metastasis to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes. | |

| IIIA1 | Positive retroperitoneal lymph nodes only (cytologically or histologically proven): |

|

| IIIA1(I): Metastasis ≤10 mm in greatest dimension. | ||

| IIIA1(ii): Metastasis >10 mm in greatest dimension. | ||

| IIIA2 | Microscopic extrapelvic (above the pelvic brim) peritoneal involvement with or without positive retroperitoneal lymph nodes. | |

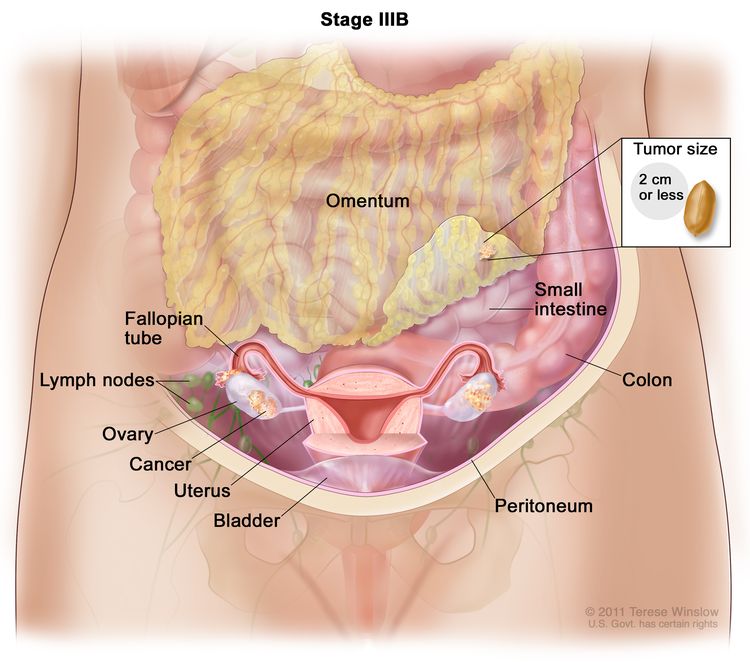

| IIIB | Macroscopic peritoneal metastasis beyond the pelvis ≤2 cm in greatest dimension, with or without metastasis to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes. |

|

| IIIC | Macroscopic peritoneal metastasis beyond the pelvis >2 cm in greatest dimension, with or without metastasis to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes (includes extension of tumor to capsule of liver and spleen without parenchymal involvement of either organ). |

|

| Stage | Definition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique. | ||

| aAdapted from FIGO Committee for Gynecologic Oncology.[1] | ||

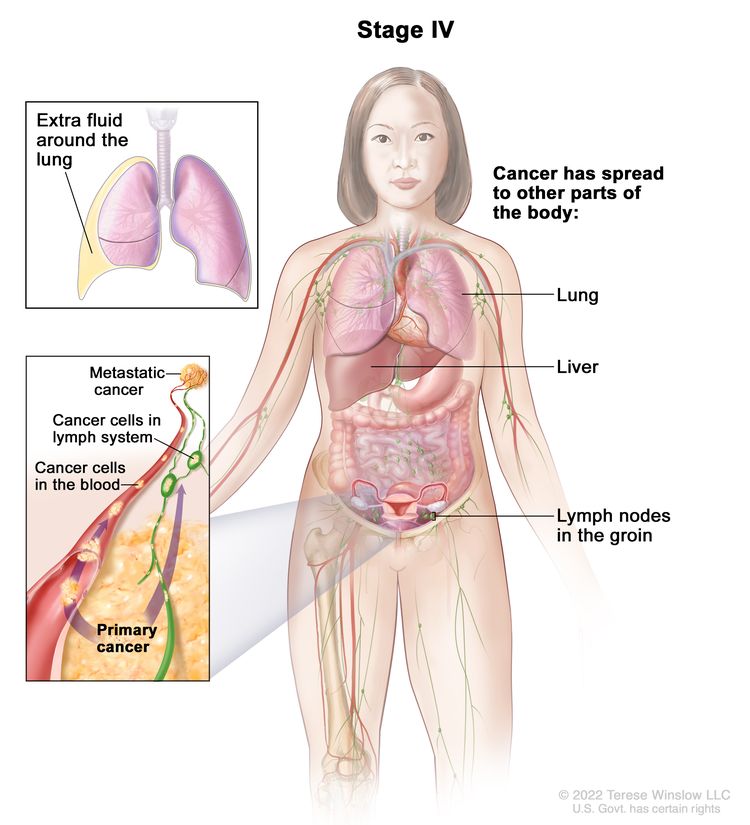

| IV | Distant metastasis excluding peritoneal metastases. |

|

| IVA | Pleural effusion with positive cytology. | |

| IVB | Parenchymal metastases and metastases to extra-abdominal organs (including inguinal lymph nodes and lymph nodes outside of the abdominal cavity). | |

References

- Berek JS, Renz M, Kehoe S, et al.: Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum: 2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 155 (Suppl 1): 61-85, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ovary, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp 681-90.

Treatment of Early-Stage Ovarian Borderline Tumors

Treatment Options for Early-Stage Ovarian Borderline Tumors

Treatment options for early-stage ovarian borderline tumors include:

Surgery

In early-stage disease (stage I or II), no additional treatment is indicated for patients with a completely resected borderline tumor.[1]

Importance of Staging for Treatment

The value of complete staging has not been demonstrated for patients with early-stage disease, but the opposite ovary should be carefully evaluated for evidence of bilateral disease. The impact of surgical staging on therapeutic management has not been defined. However, in a study of 29 patients with presumed localized disease, 7 patients were upstaged after complete surgical staging.[2]

In two other studies, 16% and 18% of patients with presumed localized borderline tumors were upstaged as a result of a staging laparotomy.[3,4] In one of these studies, the yield for serous tumors was 30.8%, compared with 0% for mucinous tumors.[3]

In another study, patients with localized intraperitoneal disease and negative lymph nodes had a low incidence of recurrence (5%), whereas patients with localized intraperitoneal disease and positive lymph nodes had a statistically significant higher incidence of recurrence (50%).[5]

Fertility Preservation

When a patient wishes to retain childbearing potential, a unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is adequate therapy.[6,7] In the presence of bilateral ovarian cystic neoplasms, or for patients with a single ovary, a partial oophorectomy can be used to preserve fertility.[8] Some physicians stress the importance of limiting ovarian cystectomy to patients with stage IA disease whose cystectomy specimen margins are tumor free.[9]

In a large series, the relapse rate was higher for patients who underwent more conservative surgery (cystectomy > unilateral oophorectomy > total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy [TAHBSO]). However, differences were not statistically significant, and the survival rates were nearly 100% for all groups.[5,10] When childbearing is not a consideration, a TAHBSO is appropriate therapy. Once a patient's family is complete, most, but not all,[9] physicians favor removal of remaining ovarian tissue as there is risk of recurrence of a borderline tumor or, rarely, a carcinoma.[3,6]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Tropé C, Kaern J, Vergote IB, et al.: Are borderline tumors of the ovary overtreated both surgically and systemically? A review of four prospective randomized trials including 253 patients with borderline tumors. Gynecol Oncol 51 (2): 236-43, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Yazigi R, Sandstad J, Munoz AK: Primary staging in ovarian tumors of low malignant potential. Gynecol Oncol 31 (3): 402-8, 1988. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Snider DD, Stuart GC, Nation JG, et al.: Evaluation of surgical staging in stage I low malignant potential ovarian tumors. Gynecol Oncol 40 (2): 129-32, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Leake JF, Rader JS, Woodruff JD, et al.: Retroperitoneal lymphatic involvement with epithelial ovarian tumors of low malignant potential. Gynecol Oncol 42 (2): 124-30, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Leake JF, Currie JL, Rosenshein NB, et al.: Long-term follow-up of serous ovarian tumors of low malignant potential. Gynecol Oncol 47 (2): 150-8, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kaern J, Tropé CG, Abeler VM: A retrospective study of 370 borderline tumors of the ovary treated at the Norwegian Radium Hospital from 1970 to 1982. A review of clinicopathologic features and treatment modalities. Cancer 71 (5): 1810-20, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lim-Tan SK, Cajigas HE, Scully RE: Ovarian cystectomy for serous borderline tumors: a follow-up study of 35 cases. Obstet Gynecol 72 (5): 775-81, 1988. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rice LW, Berkowitz RS, Mark SD, et al.: Epithelial ovarian tumors of borderline malignancy. Gynecol Oncol 39 (2): 195-8, 1990. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Piura B, Dgani R, Blickstein I, et al.: Epithelial ovarian tumors of borderline malignancy: a study of 50 cases. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2 (4): 189-197, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Casey AC, Bell DA, Lage JM, et al.: Epithelial ovarian tumors of borderline malignancy: long-term follow-up. Gynecol Oncol 50 (3): 316-22, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Advanced-Stage Ovarian Borderline Tumors

Treatment Options for Advanced-Stage Ovarian Borderline Tumors

Treatment options for advanced-stage ovarian borderline tumors include:

Surgery

Patients with advanced disease should undergo a total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, node sampling, and aggressive cytoreductive surgery. Patients with stage III or IV disease with no gross residual tumor had a survival rate of 100% in some series, regardless of the follow-up duration.[1,2] Patients with gross residual disease had a 7-year survival rate of only 69% in a large series, [3] and survival appeared to be inversely proportional to the length of follow-up.[3]

Chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy are not indicated for patients with more advanced-stage disease and microscopic or gross residual disease. Scant evidence exists that postoperative chemotherapy or radiation therapy alters the course of this disease in any beneficial way.[1,3-6] In a retrospective study of 364 patients without residual tumor, adjuvant therapy had no effect on disease-free or corrected survival when stratified for disease stage.[7] Patients without residual tumor who received no adjuvant treatment had a survival rate equal to or greater than the treated groups. No controlled studies have compared postoperative treatment with no postoperative treatment.

In a review of 150 patients with borderline ovarian tumors, the survival of patients with residual tumors smaller than 2 cm was significantly better than survival for those with residual tumors measuring 2 cm to 5 cm or tumors measuring larger than 5 cm (P < .05).[8] It is not clear whether invasive implants imply a worse prognosis. Some investigators have correlated invasive implants with a poor prognosis,[9] while others have not.[2,10] Some studies have suggested DNA ploidy of the tumors can identify patients who will develop aggressive disease.[11,12] One study could not correlate DNA ploidy of the primary serous tumor with patient survival, but found that aneuploid invasive implants were associated with a poor prognosis.[13] No evidence indicates that treating patients with aneuploid tumors would have an impact on survival. No significant associations were found between TP53 and HER2/neu overexpression and tumor recurrence or patient survival.[14]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Barnhill D, Heller P, Brzozowski P, et al.: Epithelial ovarian carcinoma of low malignant potential. Obstet Gynecol 65 (1): 53-9, 1985. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bostwick DG, Tazelaar HD, Ballon SC, et al.: Ovarian epithelial tumors of borderline malignancy. A clinical and pathologic study of 109 cases. Cancer 58 (9): 2052-65, 1986. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Leake JF, Currie JL, Rosenshein NB, et al.: Long-term follow-up of serous ovarian tumors of low malignant potential. Gynecol Oncol 47 (2): 150-8, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Casey AC, Bell DA, Lage JM, et al.: Epithelial ovarian tumors of borderline malignancy: long-term follow-up. Gynecol Oncol 50 (3): 316-22, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tumors of the ovary: neoplasms derived from coelomic epithelium. In: Morrow CP, Curtin JP: Synopsis of Gynecologic Oncology. 5th ed. Churchill Livingstone, 1998, pp 233-281.

- Sutton GP, Bundy BN, Omura GA, et al.: Stage III ovarian tumors of low malignant potential treated with cisplatin combination therapy (a Gynecologic Oncology Group study). Gynecol Oncol 41 (3): 230-3, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kaern J, Tropé CG, Abeler VM: A retrospective study of 370 borderline tumors of the ovary treated at the Norwegian Radium Hospital from 1970 to 1982. A review of clinicopathologic features and treatment modalities. Cancer 71 (5): 1810-20, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tamakoshi K, Kikkawa F, Nakashima N, et al.: Clinical behavior of borderline ovarian tumors: a study of 150 cases. J Surg Oncol 64 (2): 147-52, 1997. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bell DA, Scully RE: Serous borderline tumors of the peritoneum. Am J Surg Pathol 14 (3): 230-9, 1990. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Michael H, Roth LM: Invasive and noninvasive implants in ovarian serous tumors of low malignant potential. Cancer 57 (6): 1240-7, 1986. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Friedlander ML, Hedley DW, Swanson C, et al.: Prediction of long-term survival by flow cytometric analysis of cellular DNA content in patients with advanced ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 6 (2): 282-90, 1988. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kaern J, Trope C, Kjorstad KE, et al.: Cellular DNA content as a new prognostic tool in patients with borderline tumors of the ovary. Gynecol Oncol 38 (3): 452-7, 1990. [PUBMED Abstract]

- de Nictolis M, Montironi R, Tommasoni S, et al.: Serous borderline tumors of the ovary. A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and quantitative study of 44 cases. Cancer 70 (1): 152-60, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Eltabbakh GH, Belinson JL, Kennedy AW, et al.: p53 and HER-2/neu overexpression in ovarian borderline tumors. Gynecol Oncol 65 (2): 218-24, 1997. [PUBMED Abstract]

Latest Updates to This Summary (02/12/2025)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

General Information About Ovarian Borderline Tumors

Added text to state that ovarian borderline tumors can also become low-grade serous tumors.

Revised text to state that the Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique reported an extremely good prognosis for ovarian borderline tumors, with a 10-year survival rate of approximately 95%.

This summary is written and maintained by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of NCI. The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or NIH. More information about summary policies and the role of the PDQ Editorial Boards in maintaining the PDQ summaries can be found on the About This PDQ Summary and PDQ® Cancer Information for Health Professionals pages.

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of ovarian borderline tumors. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewers for Ovarian Borderline Tumors Treatment are:

- Olga T. Filippova, MD (Lenox Hill Hospital)

- Marina Stasenko, MD (New York University Medical Center)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's Email Us. Do not contact the individual Board Members with questions or comments about the summaries. Board members will not respond to individual inquiries.

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board uses a formal evidence ranking system in developing its level-of-evidence designations.

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as “NCI’s PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary].”

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Ovarian Borderline Tumors Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/ovarian/hp/ovarian-borderline-tumors-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389466]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in Visuals Online, a collection of over 2,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

Based on the strength of the available evidence, treatment options may be described as either “standard” or “under clinical evaluation.” These classifications should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website’s Email Us.