Skin Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version

General Information About Skin Cancer

There are three main types of skin cancer:

- Basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

- Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

- Melanoma.

BCC and SCC are the most common forms of skin cancer and together are referred to as nonmelanoma skin cancers. This summary addresses the treatment of BCC and SCC of the skin and the related noninvasive lesion actinic keratosis. For more information about the treatment of melanoma, see Melanoma Treatment.

Incidence and Mortality

Nonmelanoma skin cancer is the most common cancer in the United States. BCC is the more common type, accounting for about three-quarters of nonmelanoma skin cancers.[1] The incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer appears to be increasing in some,[2] but not all,[3] areas of the United States. Overall U.S. incidence rates have likely been increasing for a number of years.[4] At least some of this increase may be attributable to increasing skin cancer awareness and the resulting examination and biopsy of skin lesions.

The total number and incidence rate of nonmelanoma skin cancers cannot be estimated precisely because reporting to cancer registries is not required. However, based on extrapolation of Medicare fee-for-service data to the U.S. population, it has been estimated that the total number of people treated for nonmelanoma skin cancers in 2012 was about 3.3 million.[5,6] That number exceeds all other annual new cases of cancer estimated by the American Cancer Society, which total about 2 million.[6] Although nonmelanoma skin cancer is the most common of all malignancies, it accounts for less than 0.1% of patient deaths caused by cancer.

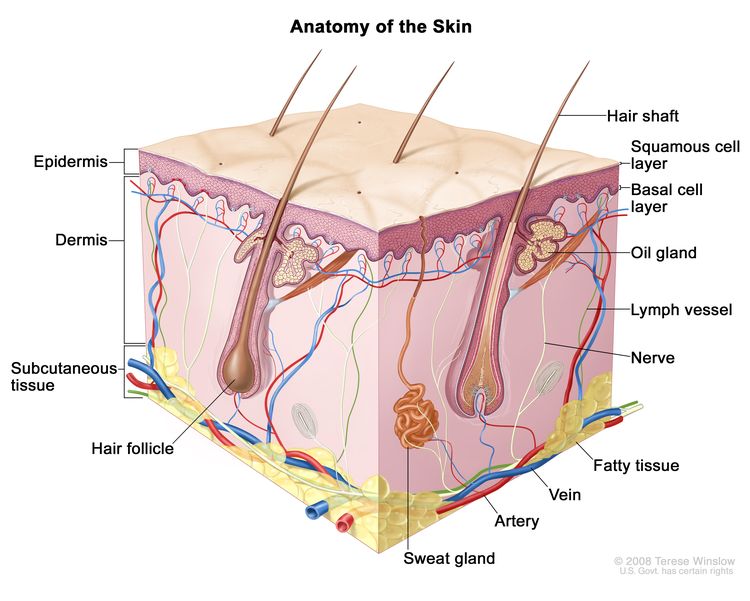

Anatomy

Risk Factors

Risk factors for nonmelanoma skin cancer include:

- Sun and UV radiation exposure (including tanning beds). Epidemiological evidence suggests that cumulative exposure to UV radiation and the sensitivity of an individual’s skin to UV radiation are risk factors for skin cancer, though the type of exposure (i.e., high-intensity exposure and short-duration exposure vs. chronic exposure) and pattern of exposure (i.e., continuous pattern vs. intermittent pattern) may differ among the three main skin cancer types.[7-9] Skin cancers are more common in the southern latitudes of the Northern hemisphere.

- History of sunburns. People who have had sunburns are predisposed to the development of SCC.

- Light complexion and eye color. Individuals with a light complexion (fair skin that freckles and burns easily), light-colored eyes (blue, green, or other light-colored eyes), and light-colored hair (red or blond) who have had substantial exposure to sunlight are at an increased risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancer.

- Family history or personal history of BCC, SCC, actinic keratosis, familial dysplastic nevus syndrome, or atypical nevi.

- Chronic cutaneous inflammation. People with chronic cutaneous inflammation, as seen in long-standing skin ulcers, are predisposed to the development of SCC.

- Immune suppression. Organ transplant recipients receiving immunosuppressive drugs and individuals with immunosuppressive diseases are at an elevated risk of developing skin cancers, particularly SCC.[1]

- Other environmental exposure. Arsenic exposure and therapeutic radiation increase the risk of cutaneous SCC.[1]

Types of Skin Cancer

This evidence-based summary covers basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin and the related noninvasive lesion actinic keratosis (viewed by some pathologists as a variant of in situ SCC).[1] BCC and SCC are both of epithelial origin. Although BCC and SCC are by far the most frequent types of nonmelanoma skin cancers, approximately 82 types of skin malignancies, with a wide range of clinical behaviors, fall into the category of nonmelanoma skin cancer.[10]

Other types of malignant disease of the skin include:

- Melanoma.

- Merkel cell carcinoma.

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (e.g., mycosis fungoides).

- Kaposi sarcoma.

- Extramammary Paget disease.

- Apocrine carcinoma of the skin.

- Metastatic malignancies from various primary sites.

For more information, see Melanoma Treatment, Merkel Cell Carcinoma Treatment, Mycosis Fungoides and Other Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas Treatment, and Kaposi Sarcoma Treatment.

Basal cell carcinoma

BCC is at least three times more common than SCC in nonimmunocompromised patients. It usually occurs in sun-exposed areas of skin, with the nose being the most common site. Although there are many different clinical presentations for BCC, the most characteristic type is the asymptomatic nodular or nodular ulcerative lesion that is elevated from the surrounding skin, has a pearly quality, and contains telangiectatic vessels.

BCCs are composed of nonkeratinizing cells derived from the basal cell layer of the epidermis. They are slow growing and rarely metastasize. BCC tends to be locally destructive and can result in serious deforming damage if left untreated or if local recurrences cannot be completely excised. High-risk areas for tumor recurrence after initial treatment include the central face (e.g., periorbital region, eyelids, nasolabial fold, or nose-cheek angle), postauricular region, pinna, ear canal, forehead, and scalp.[11]

Morpheaform type is a specific BCC subtype. This subtype typically appears as a scar-like, firm plaque. Because of indistinct clinical tumor margins, morpheaform type is difficult to treat adequately with traditional treatments.[12]

BCCs often have a characteristic variant in the PTCH1 tumor suppressor gene, although the mechanism of carcinogenesis is not clear.[1]

Squamous cell carcinoma

People with chronic sun damage, history of sunburns, arsenic exposure, chronic cutaneous inflammation (as seen in long-standing skin ulcers), and previous radiation therapy are predisposed to the development of SCC. SCCs tend to occur on sun-exposed portions of the skin, such as the ears, lower lip, and dorsa of the hands. SCCs that develop from actinic keratosis on sun-exposed skin are less likely to metastasize and these patients have a better prognosis than those who develop de novo SCCs or SCCs on non–sun-exposed skin.[12]

SCCs are composed of keratinizing cells. These tumors are more aggressive than BCCs and have a range of growth, invasive, and metastatic potential. Prognosis is associated with the degree of differentiation, and tumor grade is reported as part of the staging system.[10] A four-grade system (G1–G4) is most common, but two- and three-grade systems may also be used.

Variants in the PTCH1 tumor suppressor gene have been reported in SCCs removed from patients with a prior history of multiple BCCs.[13]

SCC in situ (also called Bowen disease) is a noninvasive lesion. Distinguishing SCC in situ pathologically from a benign inflammatory process may be difficult.[1] The risk of development into invasive SCC is low, reportedly in the range of 3% to 4%.[14]

Actinic keratosis

Actinic keratoses are potential precursors of SCC, but the rate of progression is extremely low, and most do not become SCCs. These typically red, scaly patches usually arise on areas of chronically sun-exposed skin and are likely to be found on the face and dorsal aspects of the hand.

Diagnostic and Staging Evaluation

BCC and SCC are usually diagnosed based on routine histopathology obtained from a shave, punch, incisional, or excisional biopsy.[1]

Other tests and procedures that may be used to diagnose and stage BCC and SCC of the skin include:

- Physical examination, including skin examination and history.

- Chest x-ray.

- Computed tomography (CT) scan or positron emission tomography (PET)–CT scan of the head and neck or chest.

- Ultrasonography of the regional lymph nodes.

- Lymph node biopsy.

Ophthalmic examination or evaluation is performed to diagnose and stage eyelid carcinoma.

References

- Reszko A, Aasi SZ, Wilson LD, et al.: Cancer of the skin. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA: Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 9th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011, pp 1610-33.

- Athas WF, Hunt WC, Key CR: Changes in nonmelanoma skin cancer incidence between 1977-1978 and 1998-1999 in Northcentral New Mexico. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 12 (10): 1105-8, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Harris RB, Griffith K, Moon TE: Trends in the incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancers in southeastern Arizona, 1985-1996. J Am Acad Dermatol 45 (4): 528-36, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al.: Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol 146 (3): 283-7, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Feldman SR, et al.: Incidence Estimate of Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer (Keratinocyte Carcinomas) in the U.S. Population, 2012. JAMA Dermatol 151 (10): 1081-6, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2025. American Cancer Society, 2025. Available online. Last accessed January 16, 2025.

- Koh HK: Cutaneous melanoma. N Engl J Med 325 (3): 171-82, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Preston DS, Stern RS: Nonmelanoma cancers of the skin. N Engl J Med 327 (23): 1649-62, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- English DR, Armstrong BK, Kricker A, et al.: Case-control study of sun exposure and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Int J Cancer 77 (3): 347-53, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cutaneous carcinoma of the head and neck. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp 171–81.

- Dubin N, Kopf AW: Multivariate risk score for recurrence of cutaneous basal cell carcinomas. Arch Dermatol 119 (5): 373-7, 1983. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wagner RF, Casciato DA: Skin cancers. In: Casciato DA, Lowitz BB, eds.: Manual of Clinical Oncology. 4th ed. Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins, 2000, pp 336-373.

- Ping XL, Ratner D, Zhang H, et al.: PTCH mutations in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Invest Dermatol 116 (4): 614-6, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kao GF: Carcinoma arising in Bowen's disease. Arch Dermatol 122 (10): 1124-6, 1986. [PUBMED Abstract]

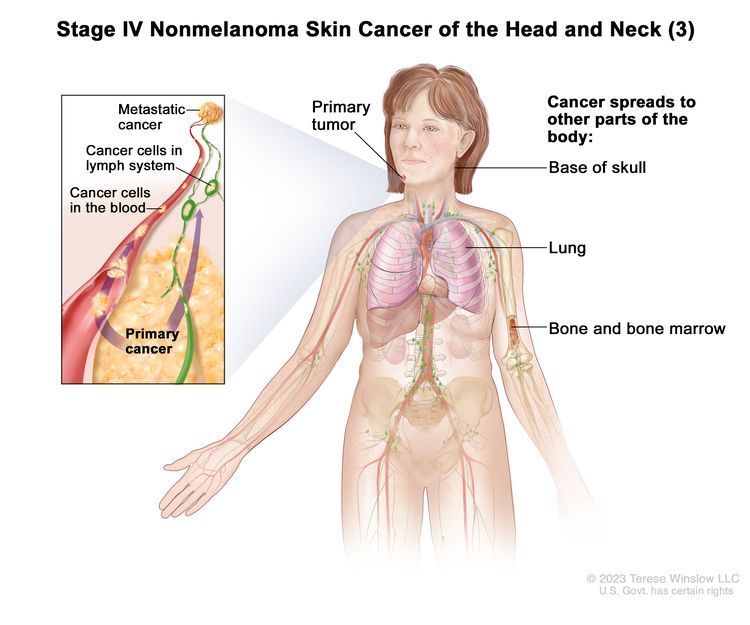

Stage Information for Skin Cancer

There are separate staging systems in the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer’s (AJCC's) AJCC Cancer Staging Manual for carcinoma of the eyelid and for cutaneous carcinoma of the head and neck. The cutaneous carcinoma staging system addresses cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and cutaneous basal cell carcinoma (BCC).[1,2] The staging system for carcinomas of the eyelid addresses carcinomas of all histologies.

Regional lymph nodes should be routinely examined in all cases of SCC, especially for the following cases:

- High-risk tumors appearing on the lips, on the ears, and in the perianal and perigenital regions.

- High-risk areas of the hand.

- Sites of chronic ulceration or inflammation, or burn scars.

- Sites of previous radiation therapy treatment.

BCC rarely metastasizes, so a metastatic workup is usually not necessary.

There are several factors that correlate with poor prognosis for recurrence and metastasis. They apply primarily to patients with SCC and an aggressive subset of nonmelanoma skin carcinoma, but rarely to patients with BCC, and include:[1]

- Extranodal extension.

- Tumor diameter.

- Depth of tumor.

- Anatomical site.

- Perineural invasion.

- Histopathological grade or differentiation and desmoplasia.

- Extension to bony structures.

- Nodal disease.

- Immunosuppression and advanced disease.

- Overall health.

- Comorbidity.

- Lifestyle factors.

- Tobacco use.

Even with relatively small tumor sizes, SCCs that occur in immunosuppressed patients tend to behave more aggressively than SCCs in nonimmunosuppressed patients. Although immunosuppression is not a formal part of the AJCC staging system, it is recommended that centers prospectively studying SCCs record the presence and type of immunosuppression.

Staging for Cutaneous Carcinoma of the Head and Neck (Excluding Carcinomas of the Eyelid)

The AJCC has designated staging by TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) classification for cutaneous carcinoma of the head and neck, excluding carcinomas of the eyelid.[1]

| T Category | T Criteria |

|---|---|

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Cutaneous carcinoma of the head and neck. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 171–81. | |

| bDeep invasion is defined as invasion beyond the subcutaneous fat or >6 mm (as measured from the granular layer of adjacent normal epidermis to the base of the tumor); perineural invasion for T3 classification is defined as tumor cells within the nerve sheath of a nerve lying deeper than the dermis or measuring ≥0.1 mm in caliber, or presenting with clinical or radiographic involvement of named nerves without skull base invasion or transgression. | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be identified. |

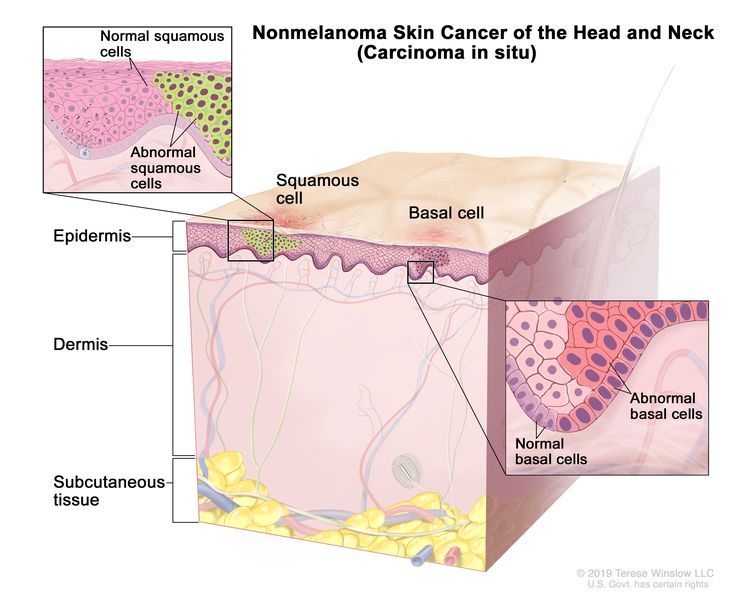

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ. |

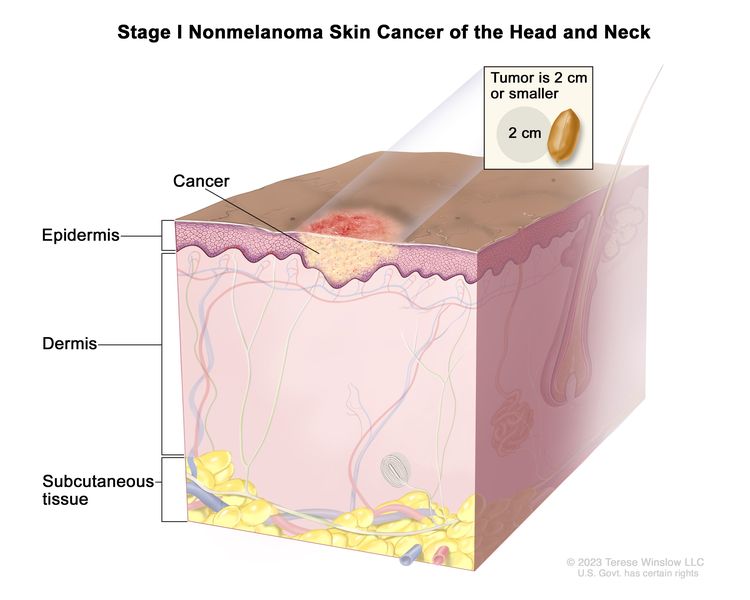

| T1 | Tumor ≤2 cm in greatest dimension. |

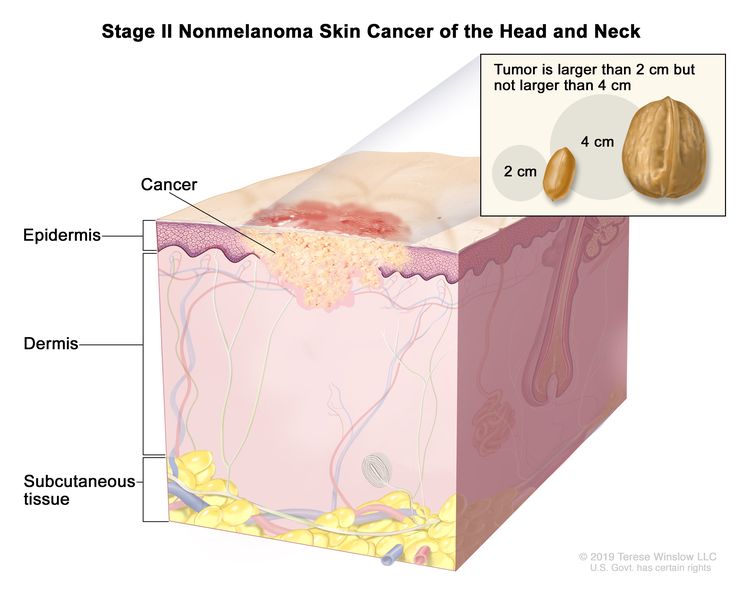

| T2 | Tumor >2 cm, but ≤4 cm in greatest dimension. |

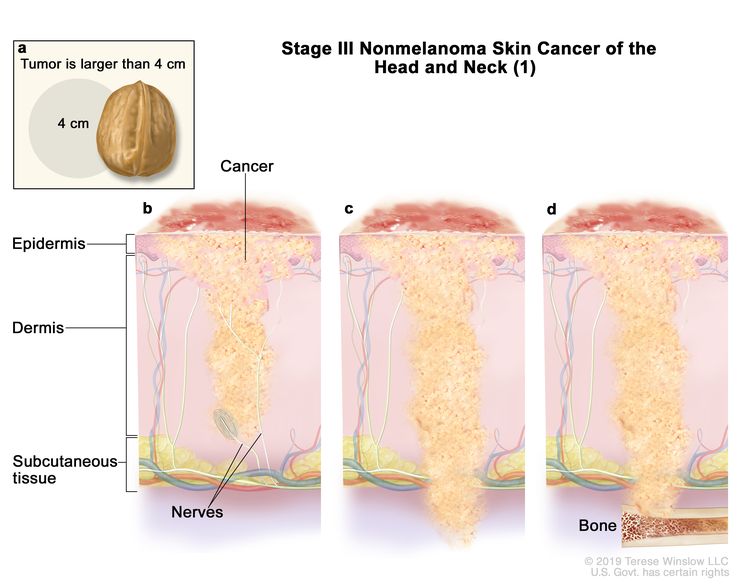

| T3 | Tumor >4 cm in maximum dimension or minor bone erosion or perineural invasion or deep invasion.b |

| T4 | Tumor with gross cortical bone/marrow, skull base invasion and/or skull base foramen invasion. |

| –T4a | Tumor with gross cortical bone/marrow invasion. |

| –T4b | Tumor with skull base invasion and/or skull base foramen involvement. |

| N Category | N Criteria |

|---|---|

| ENE = extranodal extension. | |

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Cutaneous carcinoma of the head and neck. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 171–81. | |

| bA designation of "U" or "L" may be used for any N category to indicate metastasis above the lower border of the cricoid (U) or below the lower border of the cricoid (L). Similarly, clinical and pathological ENE should be recorded as ENE negative or ENE positive. | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed. |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis. |

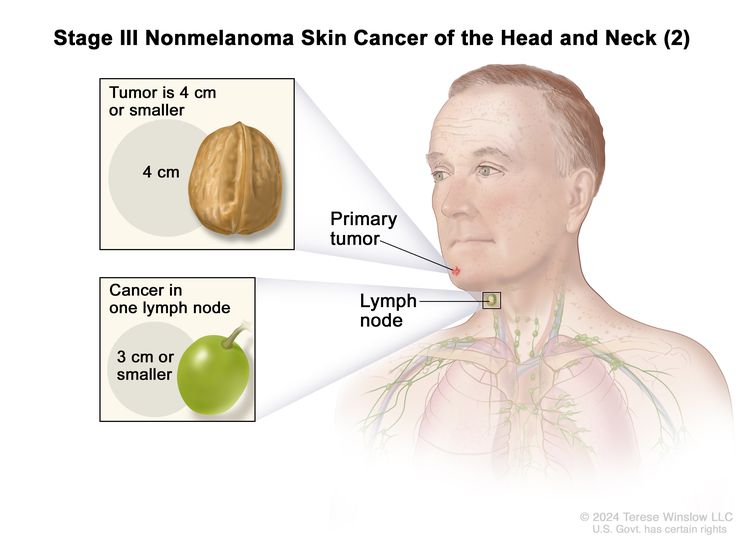

| N1 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, ≤3 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative. |

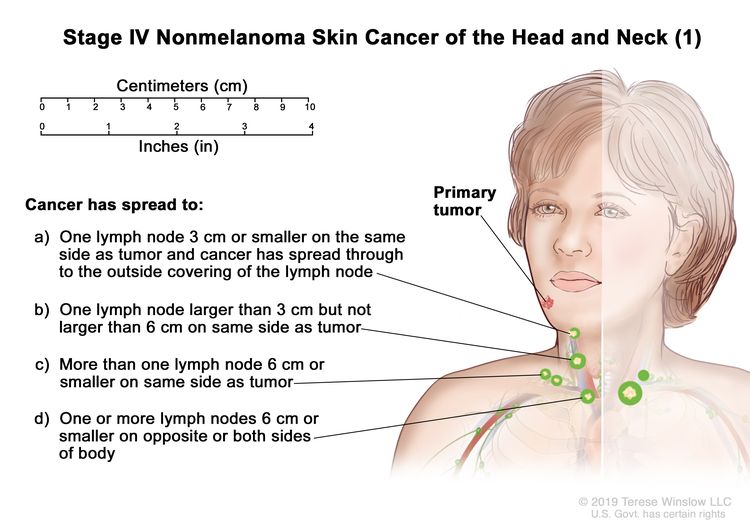

| N2 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, ≤3 cm in greatest dimension and ENE positive; or >3 cm but ≤6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative; or metastases in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none >6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative; or in bilateral or contralateral lymph node(s), none >6 cm in greatest dimension, ENE negative. |

| –N2a | Metastasis in single ipsilateral node ≤3 cm in greatest dimension and ENE positive; or a single ipsilateral node >3 cm but ≤6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative. |

| –N2b | Metastasis in multiple ipsilateral nodes, none >6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative. |

| –N2c | Metastasis in bilateral or contralateral lymph node(s), none >6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative. |

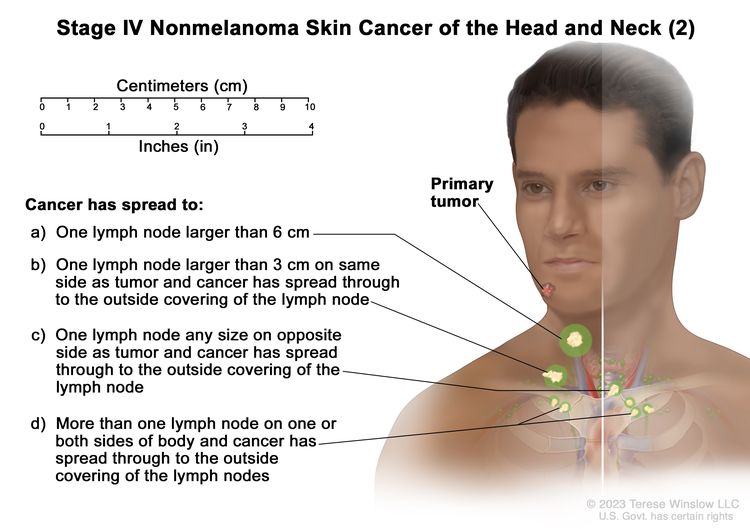

| N3 | Metastasis in a lymph node >6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative; or in a single ipsilateral node >3 cm in greatest dimension and ENE positive; or multiple ipsilateral, contralateral, or bilateral nodes, any with ENE-positive status; or a single contralateral node of any size and ENE positive. |

| –N3a | Metastasis in a lymph node >6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative. |

| –N3b | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral node >3 cm in greatest dimension and ENE positive; or multiple ipsilateral, contralateral, or bilateral nodes, any with ENE-positive status; or a single contralateral node of any size and ENE positive. |

| N Category | N Criteria |

|---|---|

| ENE = extranodal extension. | |

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Cutaneous carcinoma of the head and neck. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 171–81. | |

| bA designation of "U" or "L" may be used for any N category to indicate metastasis above the lower border of the cricoid (U) or below the lower border of the cricoid (L). Similarly, clinical and pathological ENE should be recorded as ENE negative or ENE positive. | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed. |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis. |

| N1 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, ≤3 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative. |

| N2 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral node >3 cm but ≤6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative; or metastases in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none >6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative; or in bilateral and contralateral lymph nodes, none >6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative. |

| –N2a | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral node >3 cm but ≤6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative. |

| –N2b | Metastasis in multiple ipsilateral lymph nodes, none >6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative. |

| –N2c | Metastasis in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes, none >6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative. |

| N3 | Metastasis in a lymph node >6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative; or metastasis in any node(s) and clinically overt ENE (ENE positive). |

| –N3a | Metastasis in a lymph node >6 cm in greatest dimension and ENE negative. |

| –N3b | Metastasis in any node(s) and ENE positive. |

| M Category | M Criteria |

|---|---|

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Cutaneous carcinoma of the head and neck. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 171–81. | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis. |

| M1 | Distant metastasis. |

| Stage | T | N | M | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M = distant metastasis; N = regional lymph nodes; T = primary tumor. | ||||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Cutaneous carcinoma of the head and neck. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 171–81. | ||||

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

|

| I | T1 | N0 | M0 |

|

| II | T2 | N0 | M0 |

|

| III | T1 | N1 | M0 |

|

| T2 | N1 | M0 | ||

| T3 | N0 | M0 | ||

| T3 | N1 | M0 | ||

| IV | T1 | N2 | M0 |

|

| T2 | N2 | M0 | ||

| T3 | N2 | M0 | ||

| T4 | Any N | M0 | ||

| Any T | N3 | M0 | ||

| Any T | Any N | M1 |

|

|

Staging for Carcinomas of the Eyelid

The AJCC has designated staging by TNM classification.[1] The TNM classification is used to stage all cell types of eyelid carcinomas, except melanoma.

| T Category | T Criteria |

|---|---|

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Eyelid carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 779–85. | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed. |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor. |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ. |

| T1 | Tumor ≤10 mm in greatest dimension. |

| –T1a | Tumor does not invade the tarsal plate or eyelid margin. |

| –T1b | Tumor invades the tarsal plate or eyelid margin. |

| –T1c | Tumor involves full thickness of the eyelid. |

| T2 | Tumor >10 mm but ≤20 mm in greatest dimension. |

| –T2a | Tumor does not invade the tarsal plate or eyelid margin. |

| –T2b | Tumor invades the tarsal plate or eyelid margin. |

| –T2c | Tumor involves full thickness of the eyelid. |

| T3 | Tumor >20 mm but ≤30 mm in greatest dimension. |

| –T3a | Tumor does not invade the tarsal plate or eyelid margin. |

| –T3b | Tumor invades the tarsal plate or eyelid margin. |

| –T3c | Tumor involves full thickness of the eyelid. |

| T4 | Any eyelid tumor that invades adjacent ocular, orbital, or facial structures. |

| –T4a | Tumor invades ocular or intraorbital structures. |

| –T4b | Tumor invades (or erodes through) the bony walls of the orbit or extends to the paranasal sinuses or invades the lacrimal sac/nasolacrimal duct or brain. |

| N Category | N Criteria |

|---|---|

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Eyelid carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 779–85. | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed. |

| N0 | No evidence of lymph node involvement. |

| N1 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral regional lymph node, ≤3 cm in greatest dimension. |

| –N1a | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node based on clinical evaluation or imaging findings. |

| –N1b | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node based on lymph node biopsy. |

| N2 | Metastasis in a single ipsilateral lymph node, >3 cm in greatest dimension; or in bilateral or contralateral lymph nodes. |

| –N2a | Metastasis documented based on clinical evaluation or imaging findings. |

| –N2b | Metastasis documented based on microscopic findings on lymph node biopsy. |

| M Category | M Criteria |

|---|---|

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Eyelid carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 779–85. | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis. |

| M1 | Distant metastasis. |

| Stage | T | N | M |

|---|---|---|---|

| M = distant metastasis; N = regional lymph nodes; T = primary tumor. | |||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Eyelid carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 779–85. | |||

| 0 | Tis | N0 | M0 |

| IA | T1 | N0 | M0 |

| IB | T2a | N0 | M0 |

| IIA | T2b–c | N0 | M0 |

| T3 | N0 | M0 | |

| IIB | T4 | N0 | M0 |

| IIIA | Any T | N1 | M0 |

| IIIB | Any T | N2 | M0 |

| IV | Any T | Any N | M1 |

References

- Cutaneous carcinoma of the head and neck. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp 171–81.

- Esmaeli B, Dutton JJ, Graue GF, et al.: Eyelid carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp 779-85.

Treatment Option Overview

Treatments for squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma of the skin are described in Table 10.

Treatment of Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Skin

There is a wide range of approaches for treating basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the skin, including excision, radiation therapy, cryosurgery, electrodesiccation and curettage, photodynamic or laser-beam light exposure, and topical therapies. Each of these approaches is useful in specific clinical situations. Depending on case selection, these approaches produce recurrence-free rates ranging from 85% to 95%.[1-9]

A systematic review of 27 randomized controlled trials comparing various treatments for BCC has been published.[10] Eighteen of the studies were published in full, and nine were published in abstract form only. Only 19 of the 27 trials were analyzed by intention-to-treat criteria. Because the case fatality rate of BCC is so low, the primary end point of most trials is complete response and/or recurrence rate after treatment. Most of the identified studies were not of high quality and had short follow-up periods, which will lead to overestimations of tumor control; only one study had a follow-up period of as long as 4 years. A literature review of recurrence rates in case series with long-term follow-up after treatment of BCCs indicated that only 50% of recurrences occurred within the first 2 years, 66% after 3 years, and 18% after 5 years.[11] A common finding was that the 10-year recurrence rates were about double the 2-year recurrence rates.

Treatment of Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Skin (Localized Disease)

Treatment options for BCC of the skin (localized disease) include:

Surgical excision with margin evaluation

A traditional surgical treatment, surgical excision with margin evaluation usually relies on surgical margins ranging from 3 mm to 10 mm, depending on the diameter of the tumor. Re-excision may be required if the surgical margin is found to be inadequate on permanent sectioning. In one trial, 35 of 199 primary BCCs (18%) were incompletely excised by the initial surgery and underwent a re-excision.[12] In addition, many laboratories examine only a small fraction of the total tumor margin pathologically. Therefore, the declaration of tumor-free margins can be subject to sampling error.[13]

In randomized trials, excision has been compared with radiation therapy, Mohs micrographic surgery, photodynamic therapy (PDT), and cryosurgery.

Evidence (surgical excision with margin evaluation):

- In a single-center trial, 360 patients with facial BCCs smaller than 4 cm in diameter were randomly assigned to undergo either surgical excision or radiation therapy (55% interstitial brachytherapy, 33% contact radiation therapy, and 12% conventional external-beam radiation therapy [EBRT]).[14][Level of evidence B1] Excisional margins, assessed by frozen section during the procedure in 91% of cases, had to be at least 2 mm, with re-excision if necessary. Thirteen patients were not treated and were dropped from the analysis.

- At 4 years (mean follow-up of 41 months), the actuarial failure rates (confirmed persistent or recurrent tumor) were 0.7% in the surgery arm and 7.5% in the radiation therapy arm (P = .003).[15][Level of evidence B1]

- The cosmetic results were also rated as better after surgery by both patients and dermatologists, and also by three independent professionals. At 4 years, 87% of surgery patients rated cosmesis as good, versus 69% of radiation therapy patients.[15]

- In a two-center, intent-to-treat analysis, 374 patients with 408 primary facial BCCs were randomly assigned to undergo either surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery with at least a 3-mm margin around the visible tumor until there were no positive margins in either case.[12][Level of evidence B1]

- After 30 months of follow-up, the recurrence rate was 5 out of 171 tumors (3%) in the excision group and 3 out of 160 (2%) in the Mohs micrographic surgery group (absolute difference, 1%; 95% confidence interval [CI], -2.5% to +3.7%; P = .724). There was no difference in complication rates, and overall cosmetic outcomes were similar.[12][Level of evidence B1]

- Total operative costs were nearly twice as high in the Mohs group (405.79 Euros vs. 216.86 Euros; P < .001).

- A multicenter randomized trial included 101 adults with previously untreated nodular skin BCCs, excluding lesions of the midface, orbital areas, and ears. Patients were treated with either excision (at least 5-mm margins) or PDT using topical methyl aminolevulinate cream (160 mg/g) followed by red-light exposure (wavelength 570–670 nm, 75 J/cm2) twice, 7 days apart.[16][Level of evidence B3] A per-protocol/per-lesion analysis was performed on the 97 patients who had an excision or at least one cycle of PDT.

- At 3 months, the complete response (CR) rate was 98% of lesions (51 of 52) in the surgery group versus 91% of lesions (48 of 53) in the PDT group (P = .25). CR rates assessed at 12 months were 96% for the surgery group versus 83% for the PDT group (P = .15).[16][Level of evidence B3] The investigators interpreted the results as noninferiority of PDT, but the study may have been underpowered.

- Both the investigators and the patients rated the cosmetic results as either excellent or good in a higher proportion of PDT treatments at each time point of follow-up. At 12 months, patient ratings of excellent or good were 98% in the PDT group versus 84% in the surgery group (P = .03), and investigator ratings were 79% versus 38% (P = .001).

- In a randomized single-center trial, 96 primary BCCs (patient number unclear) smaller than 2 cm in diameter involving the head and neck area were randomly assigned to either excision with a 3-mm safe margin or cryosurgery (i.e., curettage plus two freeze-thaw cycles by liquid nitrogen spray gun).[17][Level of evidence B3]

- At 1 year, there were no recurrences in the excision group versus three recurrences in the cryosurgery group (P = NS), but this is a very short follow-up time.[17][Level of evidence B3]

- Patients and five independent professionals who were blinded to the treatment arm rated the cosmetic outcomes. Their overall assessments favored excision.

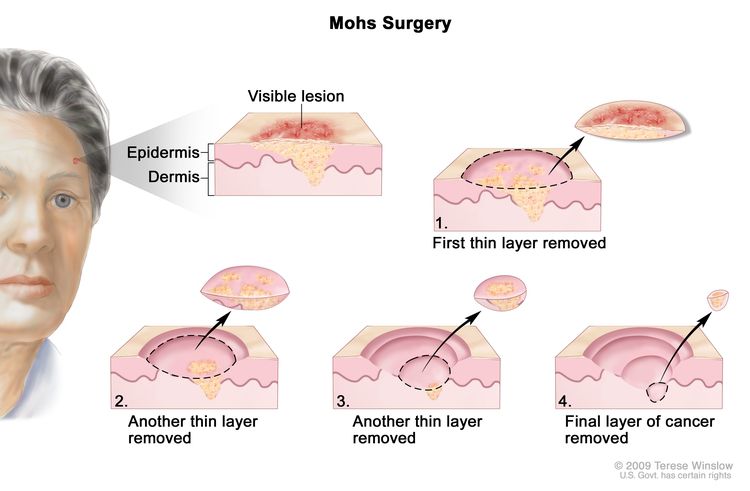

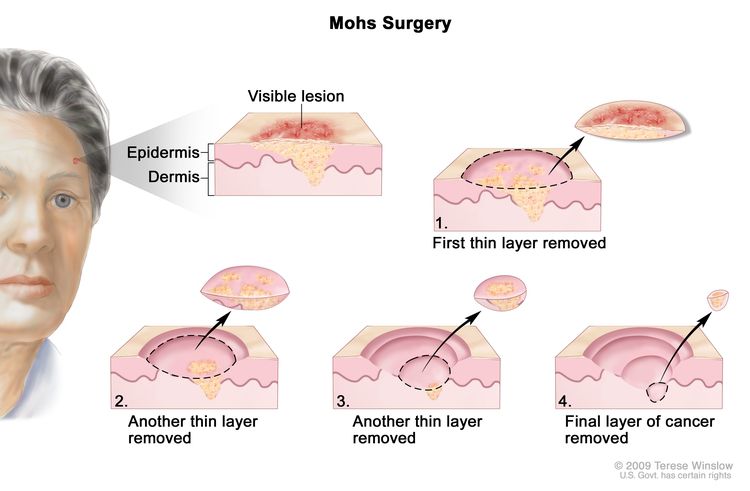

Mohs micrographic surgery

Mohs micrographic surgery is a form of tumor excision that involves progressive radial sectioning and real-time examination of the resection margins until adequate uninvolved margins have been achieved, avoiding wider margins than needed. It is a specialized technique used to achieve the narrowest margins necessary to avoid tumor recurrence while maximally preserving cosmesis. The tumor is microscopically delineated, with serial radial resection, until it is completely removed as assessed with real-time frozen sections. Noncontrolled case series suggested that the disease control rates were superior to other treatment methods for BCC.[18-20] However, as noted in the Surgical excision with margin evaluation section, the disease control rate was not clearly better when it was directly compared with the disease control rate for surgical excision of facial BCCs in a randomized trial of primary BCCs.[12]

This surgery is best suited to the management of tumors that have recurred after initial incision or of tumors in cosmetically sensitive areas (e.g., eyelid periorbital area, nasolabial fold, nose-cheek angle, posterior cheek sulcus, pinna, ear canal, forehead, scalp, fingers, and genitalia).[19,21] It is also used to treat tumors with poorly defined clinical borders.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is particularly useful in the management of patients with primary lesions that would otherwise require difficult or extensive surgery (e.g., lesions on the nose or ears).[22] Radiation therapy eliminates the need for skin grafting when surgery would result in an extensive defect. Cosmetic results are generally good, with a small amount of hypopigmentation or telangiectasia in the treatment port. Radiation therapy can also be used for lesions that recur after a primary surgical approach.[23]

Radiation therapy is avoided in patients with conditions that predispose them to radiation-induced cancers, such as xeroderma pigmentosum or basal cell nevus syndrome.

Evidence (radiation therapy):

- As noted above, radiation therapy has been compared with excision in a randomized trial that showed better response and cosmesis associated with surgery.[14,15][Level of evidence B1]

- In a single-center trial, 93 patients with BCC were randomly assigned to receive either EBRT (130 kV x-rays, dosimetry depending on lesion size) or cryotherapy (two freeze-thaw cycles with liquid nitrogen by spray gun). Patients with lesions on the nose or ear were excluded because the investigators felt that EBRT is the treatment of choice for tumors in these locations.[24][Level of evidence B3]

- Radiation was superior to cryotherapy in local control at 2 years.

- By 1 year, the recurrence rate was 4% in the radiation arm and 39% in the cryotherapy arm in a per-protocol analysis. The investigators did not perform a statistical analysis, but the authors of a systematic literature review calculated a relative risk of 0.11 in favor of radiation (95% CI, 0.03–0.43).[10][Level of evidence B3]

Curettage and electrodesiccation

Curettage and electrodesiccation is a widely employed method for removing primary BCCs, especially superficial lesions of the neck, trunk, and extremities that are considered to be at low risk of recurrence. A sharp curette is used to scrape the tumor down to its base, followed by electrodesiccation of the lesion base. Although curettage and electrodesiccation is a quick method for destroying the tumor, the adequacy of treatment cannot be assessed immediately because the surgeon cannot visually detect the depth of microscopic tumor invasion. This procedure is also sometimes called electrosurgery.

Evidence (curettage and electrodesiccation):

- A Cochrane Collaboration systematic review found no randomized trials comparing this treatment method with other approaches.[10]

- In a large, single-center case series of 2,314 previously untreated BCCs managed at a major skin cancer unit, the 5-year recurrence rate of BCCs of the neck, trunk, and extremities after curettage and electrodesiccation was 3.3%. However, rates increased substantially for tumors larger than 6 mm in diameter at other anatomical sites.[25][Level of evidence C2]

Cryosurgery

Cryosurgery may be considered for patients with small, clinically well-defined primary tumors.[26-28] It is infrequently used for the management of BCC, but cryosurgery may be useful for patients with medical conditions that preclude other types of surgery.[8,29-35] Contraindications for cryosurgery include:

- Abnormal cold tolerance.

- Cryoglobulinemia or cryofibrinogenemia.

- Raynaud disease (in the case of lesions on the hands and feet).

- Platelet deficiency disorders.

- Tumors of the scalp, ala nasi, nasolabial fold, tragus, postauricular sulcus, free eyelid margin, upper lip vermillion border, and lower legs.

- Tumors near nerves.

Caution should also be used before treating nodular ulcerative neoplasia more than 3 cm in diameter, carcinomas fixed to the underlying bone or cartilage, tumors situated on the lateral margins of the fingers and at the ulnar fossa of the elbow, or recurrent carcinomas following surgical excision. Permanent pigment loss at the treatment site is unavoidable, so the treatment is not well suited to patients with dark skin.

Edema is common after treatment, especially around the periorbital region, temple, and forehead. Treated tumors usually exude necrotic material, after which an eschar forms and persists for about 4 weeks. Atrophy and hypertrophic scarring have been reported, as have instances of motor and sensory neuropathy.

Evidence (cryosurgery):

- As noted in the Radiation therapy section, a small 93-patient trial compared cryosurgery with radiation therapy, with only 1 year of follow-up.[24][Level of evidence B3]

- There was a statistically significant higher recurrence rate with cryosurgery than with radiation therapy (39% vs. 4%).

- In a small, single-center, randomized study, 88 patients were assigned to undergo either cryosurgery in two freeze-thaw cycles; or PDT using delta-aminolevulinic acid as the photosensitizing agent and 635 nm wavelength light with 60 J/cm2 energy delivered by neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) laser.[36][Level of evidence B1]

- Overall clinical efficacy was similar in evaluable lesions at 1 year (5 of 39 recurrences for cryosurgery vs. 2 of 44 recurrences for PDT), but more re-treatments were needed with PDT to achieve complete responses.[36][Level of evidence B1]

- Cosmetic outcomes favored PDT (93% good or excellent after PDT vs. 54% after cryosurgery, P < .001).

- In another randomized study of 118 patients, reported in abstract form, cryosurgery was compared with PDT using methyl aminolevulinic acid.[37,38][Level of evidence B3]

- Tumor control rates at 3 years were similar (74%), but cosmetic outcomes were better in the PDT group. These cryosurgery-PDT comparisons were reported on a per-protocol basis rather than an intent-to-treat basis.[37,38][Level of evidence B3]

Photodynamic therapy

PDT with photosensitizers is used in the management of a wide spectrum of superficial epithelial tumors.[39] A topical photosensitizing agent such as 5-aminolevulinic acid or methyl aminolevulinate is applied to the tumor, followed by exposure to a specific wavelength of light (laser or broad band), depending on the absorption characteristics of the photosensitizer. In the case of multiple BCCs, the use of short-acting systemic (intravenous) photosensitizers such as verteporfin has been investigated.[40] Upon light activation, the photosensitizer reacts with oxygen in the tissue to form singlet oxygen species, resulting in local cell destruction.

Evidence (PDT):

- In case series, PDT has been associated with high initial CR rates. However, substantial regrowth rates of up to 50% have been reported with long-term follow-up.[39]

- A randomized trial of PDT versus excision is described in the Surgical excision with margin evaluation section.[16]

- Two small trials, one reported in abstract form, comparing PDT with cryosurgery are summarized in the Cryosurgery section, showing similar antitumor efficacy but better cosmesis with PDT.[36-38]

Topical fluorouracil (5-FU)

Topical 5-FU, as a 5% cream, may be useful in specific limited circumstances. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved this treatment for superficial BCCs in patients for whom conventional methods are impractical, such as individuals with multiple lesions or difficult treatment sites. Safety and efficacy in other indications have not been established.[41,42][Level of evidence C3] Given the superficial nature of the effects of topical 5-FU, nonvisible dermal involvement may persist, giving a false impression of treatment success. In addition, the brisk accompanying inflammatory reaction may cause substantial skin toxicity and discomfort in a large proportion of patients.

Imiquimod topical therapy

Imiquimod is an agonist for the toll-like receptor 7 and/or 8, inducing a helper T-cell cytokine cascade and interferon production. It purportedly acts as an immunomodulator.

Although the FDA approved imiquimod for treatment of superficial BCCs, some investigators in the field do not recommend it for initial monotherapy for BCC. Some reserve its use for patients with small lesions in low-risk sites who cannot undergo treatment with more established therapies.[42] Imiquimod is available as a 5% cream and is used in schedules ranging from twice weekly to twice daily over 5 to 15 weeks. Most of the experience is limited to case series of BCCs that are smaller than 2 cm2 in area and that are not in high-risk locations (e.g., within 1 cm of the hairline, eyes, nose, mouth, or ear; or in the anogenital, hand, or foot regions).[42] Follow-up times have also been generally short. Reported CR rates vary widely, from about 40% to 100%.[42][Level of evidence C3]

There have been a number of randomized trials of imiquimod.[43-48] However, the designs of all of them make interpretation of long-term efficacy impossible. Most were industry-sponsored dose-finding studies, with small numbers of patients on any given regimen. In addition, patients were only monitored for 6 to 12 weeks, with excision at that time to determine histological response.[42][Level of evidence B3]

Carbon dioxide laser

The carbon dioxide laser is used very infrequently in the management of BCC because of the difficulty in controlling tumor margins.[49] Few clinicians have extensive experience with the technique for BCC treatment. There are no randomized trials comparing it with other modalities.

Treatment of Metastatic Basal Cell Carcinoma (or Locally Advanced Disease Untreatable by Local Modalities)

Treatment options for metastatic BCC of the skin (or locally advanced disease untreatable by local modalities) include:

- Hedgehog pathway inhibitors.

- Vismodegib.

- Sonidegib.

- Chemotherapy.

Hedgehog pathway inhibitors

BCCs frequently exhibit constitutive activation of the Hedgehog/PTCH1 signaling pathway. Vismodegib and sonidegib, two inhibitors of Smoothened, a transmembrane protein involved in the Hedgehog pathway, are approved for the treatment of adults with metastatic BCC, patients with locally advanced BCC that has recurred after surgery, and patients who are not candidates for surgery or radiation therapy.

Evidence (vismodegib):

- FDA approval was supported by an international, multicenter, open-label, two-cohort trial enrolling 104 patients: 33 with metastatic BCC and 71 with locally advanced BCC with inoperable disease or for whom surgery was inappropriate. Patients received vismodegib 150 mg daily.[50][Level of evidence C3] Objective response rate (RR) assessed by an independent review committee was the primary end point. The study was sized to test whether the RR was higher than 10% in patients with metastatic BCC and higher than 20% in patients with locally advanced BCC by exact binomial 1-sided tests. Of the 104 patients, 96 were evaluable for RR, with 8 patients who had locally advanced BCC excluded from analysis after the independent pathologist did not identify BCC in the biopsy specimens. In both cohorts, the median duration of treatment was 10.2 months (range, 0.7–18.7 months).

- In 33 patients with metastatic BCC, the RR was 30% (95% CI, 16%–48%; P = .001). In 63 patients with locally advanced BCC, the RR was 43% (95% CI, 31%–56%; P < .001), with complete responses in 13 patients (21%). In both cohorts, the median duration of response was 7.6 months.[50][Level of evidence C3]

- The most common adverse events were muscle spasms, alopecia, dysgeusia, weight loss, and fatigue. Adverse events led to the discontinuation of vismodegib in 12% of patients.

- There were fatal adverse events in seven patients: three deaths from unknown causes; and one death each from hypovolemic shock, myocardial infarction, meningeal disease, and ischemic stroke. The relationship between the study drug and the deaths is unknown.

Evidence (sonidegib):

- Sonidegib was evaluated at two doses in a multinational, double-blind, multiple-cohort trial conducted in patients with metastatic BCC (n = 36) or locally advanced BCC (n = 194).[51]Level of evidence B3] Patients were randomly assigned (in a 2:1 fashion) to receive either 200 mg or 800 mg orally, once a day. The primary end point was RR, with data collected up to 6 months after randomization of the last patient and determined by blinded central review. A sample size of 210 patients was targeted to ensure 150 patients for the primary efficacy analysis, which required locally advanced disease to be assessable by modified Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria. Success was prespecified as a 30% RR.

- In the 200-mg cohort, a central review identified 18 of 42 patients with locally advanced BCC (43%; 95% CI, 28%–59%) and 2 of 13 patients with metastatic BCC (15%; 95% CI, 2%–45%) who had an objective response and qualified for the primary efficacy analysis. The median duration of response was not reached. RR was similar in the two-dose cohorts, with fewer adverse events at the lower dose, leading to FDA approval of the 200-mg once-daily dose.[51][Level of evidence B3]

- Frequent adverse events included muscle spasms, alopecia, dysgeusia, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, decreased appetite, decreased weight, myalgia, and pain.

- Four patients in the 800-mg cohort died during the study: two from cardiac death and two from metastatic disease progression.

Chemotherapy

No standard chemotherapy regimens exist, and there are only anecdotal reports in the literature.[52]

Because there is no curative therapy for metastatic BCC of the skin, clinical trials are appropriate. Information about ongoing clinical trials is available from the NCI website.

Treatment of Recurrent Nonmetastatic Basal Cell Carcinoma of the Skin

After treatment of BCC, patients are monitored clinically and examined regularly. Most recurrences occur within 5 years, but about 18% of recurrences are diagnosed beyond that point.[11]

Patients who develop a primary BCCs are also at increased risk of subsequent primary skin cancers because their sun-damaged skin is susceptible to additional cancers.[53-55] This effect is sometimes termed field carcinogenesis. Age at diagnosis of the first BCC (<65 years), red hair, and initial BCC on the upper extremities appear to be associated with a higher risk of subsequent new BCCs.[56]

Treatment options for recurrent nonmetastatic BCC of the skin include:

- Surgical excision.

- Mohs micrographic surgery.

Mohs micrographic surgery is commonly used for local recurrences of BCC.

Evidence (surgical excision vs. Mohs micrographic surgery):

- In a separate group within a randomized trial that compared excision with Mohs micrographic surgery for primary BCCs, 204 patients with recurrent BCCs were randomly assigned to undergo either excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.[12][Level of evidence B1]

- The recurrence rates were 8 of 102 patients assigned to excision and 2 of 102 patients assigned to Mohs micrographic surgery, after a mean follow-up of 2.08 years (P = NS).[12][Level of evidence B1]

- There were more postoperative complications—including wound infections, graft necrosis, or bleeding—in the excision group than in the Mohs surgery group (19% vs. 8%, P = .021).

- As with primary tumors, the operative costs associated with Mohs surgery were higher than those associated with excision (489.06 Euros vs. 323.49 Euros; P = .001).

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Shokrollahi K, Javed M, Aeuyung K, et al.: Combined carbon dioxide laser with photodynamic therapy for nodular and superficial basal cell carcinoma. Ann Plast Surg 73 (5): 552-8, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Allen KJ, Cappel MA, Killian JM, et al.: Basosquamous carcinoma and metatypical basal cell carcinoma: a review of treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery. Int J Dermatol 53 (11): 1395-403, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Clark CM, Furniss M, Mackay-Wiggan JM: Basal cell carcinoma: an evidence-based treatment update. Am J Clin Dermatol 15 (3): 197-216, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Roozeboom MH, Arits AH, Nelemans PJ, et al.: Overall treatment success after treatment of primary superficial basal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized trials. Br J Dermatol 167 (4): 733-56, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Betz CS, Rauschning W, Stranadko EP, et al.: Long-term outcomes following Foscan®-PDT of basal cell carcinomas. Lasers Surg Med 44 (7): 533-40, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jebodhsingh KN, Calafati J, Farrokhyar F, et al.: Recurrence rates of basal cell carcinoma of the periocular skin: what to do with patients who have positive margins after resection. Can J Ophthalmol 47 (2): 181-4, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Paoli J, Daryoni S, Wennberg AM, et al.: 5-year recurrence rates of Mohs micrographic surgery for aggressive and recurrent facial basal cell carcinoma. Acta Derm Venereol 91 (6): 689-93, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Peikert JM: Prospective trial of curettage and cryosurgery in the management of non-facial, superficial, and minimally invasive basal and squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Dermatol 50 (9): 1135-8, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Maghami EG, Talbot SG, Patel SG, et al.: Craniofacial surgery for nonmelanoma skin malignancy: report of an international collaborative study. Head Neck 29 (12): 1136-43, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bath-Hextall FJ, Perkins W, Bong J, et al.: Interventions for basal cell carcinoma of the skin. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD003412, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL: Long-term recurrence rates in previously untreated (primary) basal cell carcinoma: implications for patient follow-up. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 15 (3): 315-28, 1989. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Smeets NW, Krekels GA, Ostertag JU, et al.: Surgical excision vs Mohs' micrographic surgery for basal-cell carcinoma of the face: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 364 (9447): 1766-72, 2004 Nov 13-19. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Abide JM, Nahai F, Bennett RG: The meaning of surgical margins. Plast Reconstr Surg 73 (3): 492-7, 1984. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Avril MF, Auperin A, Margulis A, et al.: Basal cell carcinoma of the face: surgery or radiotherapy? Results of a randomized study. Br J Cancer 76 (1): 100-6, 1997. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Petit JY, Avril MF, Margulis A, et al.: Evaluation of cosmetic results of a randomized trial comparing surgery and radiotherapy in the treatment of basal cell carcinoma of the face. Plast Reconstr Surg 105 (7): 2544-51, 2000. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rhodes LE, de Rie M, Enström Y, et al.: Photodynamic therapy using topical methyl aminolevulinate vs surgery for nodular basal cell carcinoma: results of a multicenter randomized prospective trial. Arch Dermatol 140 (1): 17-23, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Thissen MR, Nieman FH, Ideler AH, et al.: Cosmetic results of cryosurgery versus surgical excision for primary uncomplicated basal cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Dermatol Surg 26 (8): 759-64, 2000. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Malhotra R, Huilgol SC, Huynh NT, et al.: The Australian Mohs database, part II: periocular basal cell carcinoma outcome at 5-year follow-up. Ophthalmology 111 (4): 631-6, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Thomas RM, Amonette RA: Mohs micrographic surgery. Am Fam Physician 37 (3): 135-42, 1988. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Thissen MR, Neumann MH, Schouten LJ: A systematic review of treatment modalities for primary basal cell carcinomas. Arch Dermatol 135 (10): 1177-83, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL: Mohs surgery is the treatment of choice for recurrent (previously treated) basal cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 15 (4): 424-31, 1989. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Caccialanza M, Piccinno R, Moretti D, et al.: Radiotherapy of carcinomas of the skin overlying the cartilage of the nose: results in 405 lesions. Eur J Dermatol 13 (5): 462-5, 2003 Sep-Oct. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lovett RD, Perez CA, Shapiro SJ, et al.: External irradiation of epithelial skin cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 19 (2): 235-42, 1990. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hall VL, Leppard BJ, McGill J, et al.: Treatment of basal-cell carcinoma: comparison of radiotherapy and cryotherapy. Clin Radiol 37 (1): 33-4, 1986. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Silverman MK, Kopf AW, Grin CM, et al.: Recurrence rates of treated basal cell carcinomas. Part 2: Curettage-electrodesiccation. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 17 (9): 720-6, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Divine J, Stefaniwksy L, Reddy R, et al.: A comprehensive guide to the surgical management of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Curr Probl Cancer 39 (4): 216-25, 2015 Jul-Aug. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Weshahy AH, Abdel Hay RM, Metwally D, et al.: The efficacy of intralesional cryosurgery in the treatment of small- and medium-sized basal cell carcinoma: A pilot study. J Dermatolog Treat 26 (2): 147-50, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gaitanis G, Bassukas ID: Immunocryosurgery for non-superficial basal cell carcinoma: a pro-spective, open-label phase III study for tumours ≤ 2 cm in diameter. Acta Derm Venereol 94 (1): 38-44, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Har-Shai Y, Sommer A, Gil T, et al.: Intralesional cryosurgery for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma of the lower extremities in elderly subjects: a feasibility study. Int J Dermatol 55 (3): 342-50, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gaitanis G, Kalogeropoulos CD, Bassukas ID: Cryosurgery during Imiquimod (Immunocryosurgery) for Periocular Basal Cell Carcinomas: An Efficacious Minimally Invasive Treatment Alternative. Dermatology 232 (1): 17-21, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Samain A, Boullié MC, Duval-Modeste AB, et al.: Cryosurgery and curettage-cryosurgery for basal cell carcinomas of the mid-face. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 29 (7): 1291-6, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lindgren G, Larkö O: Cryosurgery of eyelid basal cell carcinomas including 781 cases treated over 30 years. Acta Ophthalmol 92 (8): 787-92, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Nakuçi M, Bassukas ID: Office-based treatment of basal cell carcinoma with immunocryosurgery: feasibility and efficacy. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat 22 (2): 35-8, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lindemalm-Lundstam B, Dalenbäck J: Prospective follow-up after curettage-cryosurgery for scalp and face skin cancers. Br J Dermatol 161 (3): 568-76, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gaitanis G, Alexopoulos EC, Bassukas ID: Cryosurgery is more effective in the treatment of primary, non-superficial basal cell carcinomas when applied during and not prior to a five week imiquimod course: a randomized, prospective, open-label study. Eur J Dermatol 21 (6): 952-8, 2011 Nov-Dec. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wang I, Bendsoe N, Klinteberg CA, et al.: Photodynamic therapy vs. cryosurgery of basal cell carcinomas: results of a phase III clinical trial. Br J Dermatol 144 (4): 832-40, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Basset-Séguin N, Ibbotson S, Emtestam L, et al.: Photodynamic therapy using methyl aminolaevulinate is as efficacious as cryotherapy in basal cell carcinoma, with better cosmetic results. [Abstract] Br J Dermatol 149 (Suppl 64): A-P-66, 46, 2003.

- Basset-Séguin N, Ibbotson S, Emtestam L, et al.: Methyl aminolaevulinate photodynamic therapy vs. cryotherapy in primary superficial basal cell carcinoma: results of a 36-month follow-up. [Abstract] Br J Dermatol 153 (Suppl 1): A-P-30, 29. 2005.

- Hsi RA, Rosenthal DI, Glatstein E: Photodynamic therapy in the treatment of cancer: current state of the art. Drugs 57 (5): 725-34, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lui H, Hobbs L, Tope WD, et al.: Photodynamic therapy of multiple nonmelanoma skin cancers with verteporfin and red light-emitting diodes: two-year results evaluating tumor response and cosmetic outcomes. Arch Dermatol 140 (1): 26-32, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Efudex® (fluorouracil) cream, 5% [package insert]. Aliso Viejo, Ca: Valeant Pharmaceuticals International, 2005. Available online. Last accessed March 7, 2025.

- Love WE, Bernhard JD, Bordeaux JS: Topical imiquimod or fluorouracil therapy for basal and squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol 145 (12): 1431-8, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Beutner KR, Geisse JK, Helman D, et al.: Therapeutic response of basal cell carcinoma to the immune response modifier imiquimod 5% cream. J Am Acad Dermatol 41 (6): 1002-7, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Geisse JK, Rich P, Pandya A, et al.: Imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma: a double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled study. J Am Acad Dermatol 47 (3): 390-8, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Geisse J, Caro I, Lindholm J, et al.: Imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma: results from two phase III, randomized, vehicle-controlled studies. J Am Acad Dermatol 50 (5): 722-33, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Shumack S, Robinson J, Kossard S, et al.: Efficacy of topical 5% imiquimod cream for the treatment of nodular basal cell carcinoma: comparison of dosing regimens. Arch Dermatol 138 (9): 1165-71, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Marks R, Gebauer K, Shumack S, et al.: Imiquimod 5% cream in the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma: results of a multicenter 6-week dose-response trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 44 (5): 807-13, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schulze HJ, Cribier B, Requena L, et al.: Imiquimod 5% cream for the treatment of superficial basal cell carcinoma: results from a randomized vehicle-controlled phase III study in Europe. Br J Dermatol 152 (5): 939-47, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Reszko A, Aasi SZ, Wilson LD, et al.: Cancer of the skin. In: DeVita VT Jr, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA: Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. 9th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011, pp 1610-33.

- Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, et al.: Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 366 (23): 2171-9, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Migden MR, Guminski A, Gutzmer R, et al.: Treatment with two different doses of sonidegib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic basal cell carcinoma (BOLT): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 16 (6): 716-28, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Khandekar JD: Complete response of metastatic basal cell carcinoma to cisplatin chemotherapy: a report on two patients. Arch Dermatol 126 (12): 1660, 1990. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Robinson JK: Risk of developing another basal cell carcinoma. A 5-year prospective study. Cancer 60 (1): 118-20, 1987. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Karagas MR, Stukel TA, Greenberg ER, et al.: Risk of subsequent basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin among patients with prior skin cancer. Skin Cancer Prevention Study Group. JAMA 267 (24): 3305-10, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schinstine M, Goldman GD: Risk of synchronous and metachronous second nonmelanoma skin cancer when referred for Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol 44 (3): 497-9, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kiiski V, de Vries E, Flohil SC, et al.: Risk factors for single and multiple basal cell carcinomas. Arch Dermatol 146 (8): 848-55, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Skin

Localized squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the skin is a highly curable disease.[1] There are a variety of treatment approaches to localized SCC, including excision, radiation therapy, cryosurgery, and electrodesiccation and curettage.

There is little to no good-quality evidence that allows direct comparison of outcomes for patients with sporadic, clinically localized SCCs treated with local therapies. A systematic literature review found only one randomized controlled trial in the management of such patients, and that trial compared adjuvant therapy with observation after initial local therapy rather than different local therapies.[2] In that small single-center trial, 66 patients with high-risk, clinically localized SCC were randomly assigned, after surgical excision of the primary tumor (with or without radiation, depending on clinical judgment), to either receive combined isotretinoin (1 mg/kg orally per day) plus interferon alfa (3 × 106 U subcutaneously 3 times/week) for 6 months or undergo observation.[3] In the 65 evaluable patients after a median follow-up of 21.5 months, there was no difference in the combined (primary) end point of SCC recurrence or second primary tumor (45% vs. 38%; hazard ratio, 1.13; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.53–2.41), or in either of the individual components of the primary end point.[3][Level of evidence B1]

Cemiplimab and pembrolizumab, programmed death receptor-1 (PD-1) inhibitors, are the only systemic therapies for the treatment of locally advanced and metastatic cutaneous SCC. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved cemiplimab and pembrolizumab based on objective response rates (RRs) from early-phase trials.[4-6][Level of evidence C3] Toxicities associated with checkpoint inhibitors were seen, including death. Clinical trials are recommended to further identify optimal treatment. Ongoing trials include PD-1 inhibitors in the neoadjuvant, adjuvant, and advanced/metastatic settings, as monotherapy and in combinations.

Treatment of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Skin (Localized Disease)

Treatment options for SCC of the skin (localized disease) include:

Surgical excision with margin evaluation

Excision is probably the most common therapy for SCC.[7] This traditional surgical treatment usually relies on surgical margins ranging from 4 mm to 10 mm, depending on the diameter of the tumor and degree of differentiation. In a prospective case series of 141 SCCs, a 4-mm margin was adequate to encompass all subclinical microscopic tumor extension in more than 95% of well-differentiated tumors up to 19 mm in diameter. Wider margins of 6 mm to 10 mm were needed for larger or less-differentiated tumors and tumors in high-risk locations (e.g., scalp, ears, eyelids, nose, and lips).[8] Re-excision may be required if the surgical margin is inadequate on permanent sectioning.

Mohs micrographic surgery

Mohs micrographic surgery is a form of tumor excision that involves progressive radial sectioning and real-time examination of the resection margins until adequate uninvolved margins have been achieved, avoiding wider margins than needed. It is a specialized technique used to achieve the narrowest margins necessary to avoid tumor recurrence while maximally preserving cosmesis. The tumor is microscopically delineated, with serial radial resection, until it is completely removed as assessed with real-time frozen sections. However, because the technique removes tumor growing in contiguity and may miss noncontiguous in-transit cutaneous micrometastases, some practitioners remove an additional margin of skin in high-risk lesions, even after the Mohs surgical procedure confirms uninvolved margins.[7][Level of evidence C3] In case series, Mohs surgery has been associated with a lower local recurrence rate than the other local modalities,[9] but there are no randomized trials allowing direct comparison.[2]

This surgery is best suited to the management of tumors in cosmetically sensitive areas (e.g., eyelid periorbital area, nasolabial fold, nose-cheek angle, posterior cheek sulcus, pinna, ear canal, forehead, scalp, fingers, and genitalia) or for tumors that have recurred after initial excision.[10,11] Mohs micrographic surgery is also used to treat high-risk tumors with poorly defined clinical borders or with perineural invasion.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is a logical treatment choice, particularly for patients with primary lesions requiring difficult or extensive surgery (e.g., lesions on the nose, lips, or ears).[7,12] Radiation therapy eliminates the need for skin grafting in cases where surgery would result in an extensive defect. Cosmetic results are generally good, with a small amount of hypopigmentation or telangiectasia in the treatment port. Radiation therapy can also be used for lesions that recur after a primary surgical approach.[13]

Radiation therapy is avoided in patients with conditions that predispose them to radiation-induced cancers, such as xeroderma pigmentosum or basal cell nevus syndrome.

Although radiation therapy, with or without excision of the primary tumor, is used for histologically proven clinical lymph node metastases and has been associated with favorable disease-free survival rates, the retrospective nature of these case series makes it difficult to know the impact of nodal radiation on survival.[14,15][Level of evidence C2]

Curettage and electrodesiccation

Curettage and electrodesiccation is used to treat SCC of the skin. A sharp curette is used to scrape the tumor down to its base, followed by electrodesiccation of the lesion base. Although curettage and electrodesiccation is a quick method for destroying the tumor, the adequacy of treatment cannot be assessed immediately because the surgeon cannot visually detect the depth of microscopic tumor invasion. Its use is limited to small (<1 cm), well-defined, and well-differentiated tumors.[7][Level of evidence C2] This procedure is also sometimes called electrosurgery.

Cryosurgery

Cryosurgery may be considered for patients with small, clinically well-defined primary tumors. It may be useful for patients with medical conditions that preclude other types of surgery.[16,17] Contraindications for cryosurgery include:

- Abnormal cold tolerance.

- Cryoglobulinemia or cryofibrinogenemia.

- Raynaud disease (in the case of lesions on the hands and feet).

- Platelet deficiency disorders.

- Tumors of the scalp, ala nasi, nasolabial fold, tragus, postauricular sulcus, free eyelid margin, upper lip vermillion border, and lower legs.

- Tumors near nerves.

Caution should also be used before treating nodular ulcerative neoplasia larger than 3 cm in diameter, carcinomas fixed to the underlying bone or cartilage, tumors situated on the lateral margins of the fingers and at the ulnar fossa of the elbow, or recurrent carcinomas following surgical excision. Permanent pigment loss at the treatment site is unavoidable, so the treatment is not well suited to patients with dark skin.

Edema is common after treatment, especially around the periorbital region, temple, and forehead. Treated tumors usually exude necrotic material, after which an eschar forms and persists for about 4 weeks. Atrophy and hypertrophic scarring have been reported, as have instances of motor and sensory neuropathy.

Treatment of SCC in situ (Bowen disease)

The management of SCC in situ (Bowen disease) is similar to that for good-risk SCC. However, because Bowen disease is noninvasive, surgical excision, including Mohs micrographic surgery, is usually not necessary. In addition, high complete response (CR) rates are achievable with photodynamic therapy (PDT).

Evidence (PDT):

- In a multicenter trial, 229 patients (209 evaluated in a per-protocol/per-lesion analysis) were randomly assigned to receive PDT (methyl aminolevulinate + 570–670 nm red light; n = 91); placebo cream with red light (n = 15); or treatment by physician choice (cryotherapy, n = 77; topical fluorouracil [5-FU], n = 26).[18][Level of evidence B1]

- The sustained complete clinical RRs at 12 months were 80% for PDT, 67% for placebo cream with red light, and 69% for treatment of physician choice (P = .04 for the comparison between PDT and the two combined physician-choice groups).[18][Level of evidence B1]

- The cosmetic results were best in the PDT group. (For comparison, the CR rates at 3 months were 93% for PDT and 21% for placebo/PDT.)

Treatment of Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma (or Advanced Disease Untreatable by Local Modalities)

As is the case with basal cell carcinoma (BCC), metastatic and far-advanced SCC is unusual, and reports of systemic therapy are limited to case reports, small case series, or early-phase trials with tumor response as the end point.[Level of evidence C3] The metastatic rates are 5% for primary tumors of sun-exposed skin, 9% for tumors of the external ear, and 14% for tumors of the lip. Metastases occur at an even higher rate (about 38%) for primary SCCs in scar carcinomas or in nonexposed areas of skin.[9] About 69% of metastases are diagnosed within 1 year, 91% within 3 years, and 96% within 5 years.

Immunotherapy (PD-1 inhibitors)

Two PD-1 inhibitors, cemiplimab and pembrolizumab, have been approved by the FDA as systemic therapy for recurrent or metastatic SCC not amenable to curative surgery or radiation therapy (cemiplimab, pembrolizumab) and locally advanced SCC not amenable to curative surgery (cemiplimab).

Cemiplimab

The FDA approved cemiplimab for systemic therapy for metastatic or locally advanced SCC not amenable to curative surgery or radiation therapy. Approval was based on RR as assessed by an independent review committee in two open-label, multicenter, early-phase trials.[4,5][Level of evidence C3] The FDA-approved dose is a fixed-dose equivalent (350 mg as a 30-minute intravenous [IV] infusion administered every 3 weeks) of the trial dose given as 3 mg/kg IV over 30 minutes every 2 weeks. Toxicities associated with checkpoint inhibitors were seen, including death.

Evidence (cemiplimab):

- A phase I expansion cohort trial (NCT02383212) that required patients to have at least one measurable lesion enrolled patients with metastatic (n = 16) or locally advanced (n = 10) SCC. Cemiplimab was administered as 3 mg/kg IV over 30 minutes every 2 weeks.[4]

- Formal hypothesis testing was not included in phase I. However, responses, as assessed by an independent review committee, were seen in 13 of 26 patients using Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria for radiological scans.[4]

- A phase II trial (NCT02760498) entered patients into one of two cohorts: patients with metastatic SCC (nodal or distant; 59 patients) [4] or patients with locally advanced SCC who were not eligible for local surgery or radiation therapy (78 patients).[5]

Patients were required to have at least one measurable lesion and were excluded for an autoimmune disease that required systemic therapy within 5 years, previous checkpoint inhibitor therapy, solid organ transplant, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status below 1, and hepatitis or infection with HIV. Patients received treatment with 3 mg/kg IV every 2 weeks until progressive disease. RRs were assessed by an independent review committee using RECIST criteria for radiological scans and World Health Organization criteria for medical photography for a composite response. RRs were assessed after all patients had at least 6 months of follow-up.

- Metastatic disease: Twenty-eight of 59 patients had a response (47%; 95% CI, 34%−61%); 4 patients (7%) had a CR. The median duration of follow-up was 7.9 months with median duration of response not reached. When results from the 16 patients with metastatic disease in the phase I study were pooled with the results from the 59 patients with metastatic disease in the phase II cohort, the RR in 75 patients remained 47% (95% CI, 35%−59%).

- Locally advanced disease: A total of 78 patients with locally advanced disease (i.e., no nodal metastases) were enrolled in the phase II cohort. The RR was 44% (34 patients; 95% CI, 32−55), with CRs reported in 10 patients (13%). The median duration of follow-up was 9.3 months at the time of data cut-off, with a median duration of response not reached.

- Exploratory immunohistochemistry analysis did not show predictive value of baseline PD-L1.

- Adverse events were consistent with PD-1 inhibitors. In the phase II trial, approximately 7% to 8% of patients discontinued treatment because of adverse events, and there were five treatment-emergent adverse events leading to death.

Pembrolizumab

Pembrolizumab is approved for systemic therapy for recurrent or metastatic SCC not amenable to surgery or radiation therapy. Approval was based on RR as assessed by an independent review committee of a multicenter, multicohort, open-label phase II trial in patients with recurrent or metastatic SCC not amenable to surgery or radiation therapy.[6][Level of evidence C3] The cohort of patients with locally advanced disease is not yet reported. Patients received pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks. An alternate dosing regimen of pembrolizumab, 400 mg every 6 weeks, is approved across all adult indications based on pharmacokinetic modeling and exposure-response analyses.

Evidence (pembrolizumab):

- A single-arm phase II trial (KEYNOTE-629 [NCT03284424]) enrolled 105 patients into the cohort of recurrent or metastatic SCC.[6] Patients were required to have measurable disease and were excluded for an autoimmune disease or a medical condition requiring immunosuppression or an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status above grade 1. Treatment continued for up to 2 years in the absence of disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or investigator or patient decision to withdraw. If stable, patients with radiological-only evidence of progressive disease at first assessment were permitted to continue treatment until progressive disease was confirmed. The primary end point was RR per RECIST v1.1.

- An interim analysis at 11 months of follow-up (range, 0.4−16.3 months) demonstrated an RR of 34% (95% CI, 25%−44%) with four CRs. Median duration of response has not been reached (range, 3−13± months).

- Exploratory analysis of programmed death ligand 1 combined positive score by immunohistochemistry did not predict response to treatment.

- Adverse events were consistent with PD-1 inhibitors. Treatment-emergent adverse events led to discontinuation in 13 patients (12%); five (5%) were considered treatment-emergent adverse events, including pneumonitis, cranial nerve neuropathy, and renal failure. Grade 5 treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in 12 patients (11%) and included infection, cardiac failure, and respiratory failure. One death from cranial nerve neuropathy was considered treatment related.

As treatment options and long-term outcomes are limited, clinical trials are recommended. Trial options include PD-1 inhibitors and cemiplimab in the advanced setting, as well as in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings; other checkpoint inhibitors; checkpoint inhibitor combinations; and combinations with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors.

Treatment of Recurrent Nonmetastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Skin

SCCs have definite metastatic potential, and patients are monitored regularly after initial treatment. Overall, local recurrence rates after treatment of primary SCCs have ranged from about 3% to 23%, depending on anatomical site.[9] About 58% of local recurrences manifest within 1 year, 83% within 3 years, and 95% within 5 years. Tumors that are 2 cm or larger in diameter, 4 mm or greater in depth, or poorly differentiated have a relatively poor prognosis [19] and even higher local recurrence and metastasis rates than those listed.[9] Reported local recurrence rates also vary by treatment modality, with the lowest rates associated with Mohs micrographic surgery. However, at least some of the variation may be the result of patient selection factors. No randomized trials directly compare the various local treatment modalities.

Treatment options for recurrent nonmetastatic SCCs include:

- Surgical excision.

- Mohs micrographic surgery.

- Radiation therapy.

Recurrent nonmetastatic SCCs are considered high risk and are generally treated with excision, often using Mohs micrographic surgery. Radiation therapy is used for lesions that cannot be completely resected.

As is the case with BCC, patients who develop a primary SCC are also at increased risk of subsequent primary skin cancers.[20,21]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Preston DS, Stern RS: Nonmelanoma cancers of the skin. N Engl J Med 327 (23): 1649-62, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lansbury L, Leonardi-Bee J, Perkins W, et al.: Interventions for non-metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4): CD007869, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Brewster AM, Lee JJ, Clayman GL, et al.: Randomized trial of adjuvant 13-cis-retinoic acid and interferon alfa for patients with aggressive skin squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 25 (15): 1974-8, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Migden MR, Rischin D, Schmults CD, et al.: PD-1 Blockade with Cemiplimab in Advanced Cutaneous Squamous-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 379 (4): 341-351, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Migden MR, Khushalani NI, Chang ALS, et al.: Cemiplimab in locally advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: results from an open-label, phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol 21 (2): 294-305, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Grob JJ, Gonzalez R, Basset-Seguin N, et al.: Pembrolizumab Monotherapy for Recurrent or Metastatic Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Single-Arm Phase II Trial (KEYNOTE-629). J Clin Oncol 38 (25): 2916-2925, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Motley R, Kersey P, Lawrence C, et al.: Multiprofessional guidelines for the management of the patient with primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol 146 (1): 18-25, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Brodland DG, Zitelli JA: Surgical margins for excision of primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 27 (2 Pt 1): 241-8, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL: Prognostic factors for local recurrence, metastasis, and survival rates in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, ear, and lip. Implications for treatment modality selection. J Am Acad Dermatol 26 (6): 976-90, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Thomas RM, Amonette RA: Mohs micrographic surgery. Am Fam Physician 37 (3): 135-42, 1988. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rowe DE, Carroll RJ, Day CL: Mohs surgery is the treatment of choice for recurrent (previously treated) basal cell carcinoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 15 (4): 424-31, 1989. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Caccialanza M, Piccinno R, Moretti D, et al.: Radiotherapy of carcinomas of the skin overlying the cartilage of the nose: results in 405 lesions. Eur J Dermatol 13 (5): 462-5, 2003 Sep-Oct. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lovett RD, Perez CA, Shapiro SJ, et al.: External irradiation of epithelial skin cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 19 (2): 235-42, 1990. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Shimm DS, Wilder RB: Radiation therapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Am J Clin Oncol 14 (5): 383-6, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Veness MJ, Palme CE, Smith M, et al.: Cutaneous head and neck squamous cell carcinoma metastatic to cervical lymph nodes (nonparotid): a better outcome with surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy. Laryngoscope 113 (10): 1827-33, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gaitanis G, Bassukas ID: Immunocryosurgery - an effective combinational modality for Bowen's disease. Dermatol Ther 29 (5): 334-337, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Almeida Gonçalves JC: Advanced cancer of the extremities treated by cryosurgery. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 146 (4): 249-55, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Morton C, Horn M, Leman J, et al.: Comparison of topical methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy with cryotherapy or Fluorouracil for treatment of squamous cell carcinoma in situ: Results of a multicenter randomized trial. Arch Dermatol 142 (6): 729-35, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cherpelis BS, Marcusen C, Lang PG: Prognostic factors for metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Dermatol Surg 28 (3): 268-73, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Karagas MR, Stukel TA, Greenberg ER, et al.: Risk of subsequent basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin among patients with prior skin cancer. Skin Cancer Prevention Study Group. JAMA 267 (24): 3305-10, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]