Renal Cell Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version

General Information About Renal Cell Cancer

Incidence and Mortality

Estimated new cases and deaths from renal cell (kidney and renal pelvis) cancer in the United States in 2025:[1]

- New cases: 80,980.

- Deaths: 14,510.

Follow-Up and Survivorship

Renal cell cancer, also called renal adenocarcinoma or hypernephroma, can often be cured if it is diagnosed and treated when still localized to the kidney and the immediately surrounding tissue. The probability of cure is directly related to the stage or degree of tumor dissemination. Even when regional lymphatics or blood vessels are involved with the tumor, a significant number of patients can achieve prolonged survival and probable cure.[2] When distant metastases are present, disease-free survival is poor; however, some patients survive after surgical resection of all known tumor. Because most patients are diagnosed when the tumor is still relatively localized and amenable to surgical removal, approximately 75% of all patients with renal cell cancer survive for 5 years.[3] Occasionally, patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease may exhibit indolent courses lasting several years. Late tumor recurrence many years after initial treatment also occasionally occurs.

Renal cell cancer is one of the few tumors in which well-documented cases of spontaneous tumor regression in the absence of therapy exist, but this regression occurs rarely and may not lead to long-term survival.

Treatment Modalities

Surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment of this disease. Even in patients with disseminated tumor, locoregional forms of therapy may play an important role in palliating symptoms of the primary tumor or of ectopic hormone production. Systemic therapy has demonstrated only limited effectiveness.

References

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2025. American Cancer Society, 2025. Available online. Last accessed January 16, 2025.

- Sene AP, Hunt L, McMahon RF, et al.: Renal carcinoma in patients undergoing nephrectomy: analysis of survival and prognostic factors. Br J Urol 70 (2): 125-34, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- National Cancer Institute: SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Kidney and Renal Pelvis Cancer. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute. Available online. Last accessed February 17, 2025.

Cellular Classification of Renal Cell Cancer

Approximately 85% of renal cell cancers are adenocarcinomas, mostly of proximal tubular origin. Most of the remainder are transitional cell carcinomas of the renal pelvis. For more information, see Transitional Cell Cancer of the Renal Pelvis and Ureter Treatment. Adenocarcinomas may be separated into clear cell and granular cell carcinomas; however, the two cell types may occur together in some tumors. Some investigators have found that granular cell tumors have a worse prognosis, but this finding is not universal. Distinguishing between well-differentiated renal adenocarcinomas and renal adenomas can be difficult. The diagnosis is usually made arbitrarily based on the size of the mass, but size alone should not influence the treatment approach because metastases can occur with lesions as small as 0.5 cm.

Stage Information for Renal Cell Cancer

The staging system for renal cell cancer is based on the degree of tumor spread beyond the kidney.[1-3] Involvement of blood vessels may not be a poor prognostic sign if the tumor is otherwise confined to the substance of the kidney. Abnormal liver function test results may be caused by a paraneoplastic syndrome that is reversible with tumor removal, and these types of results do not necessarily represent metastatic disease. Except when computed tomography (CT) examination is equivocal or when iodinated contrast material is contraindicated, CT scanning is as good as or better than magnetic resonance imaging for detecting renal masses.[4]

AJCC Stage Groupings and TNM Definitions

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) has designated staging by TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) classification to define renal cell cancer.[5]

| Stage | TNM | Definition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis. | |||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Kidney. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 739–48. | |||

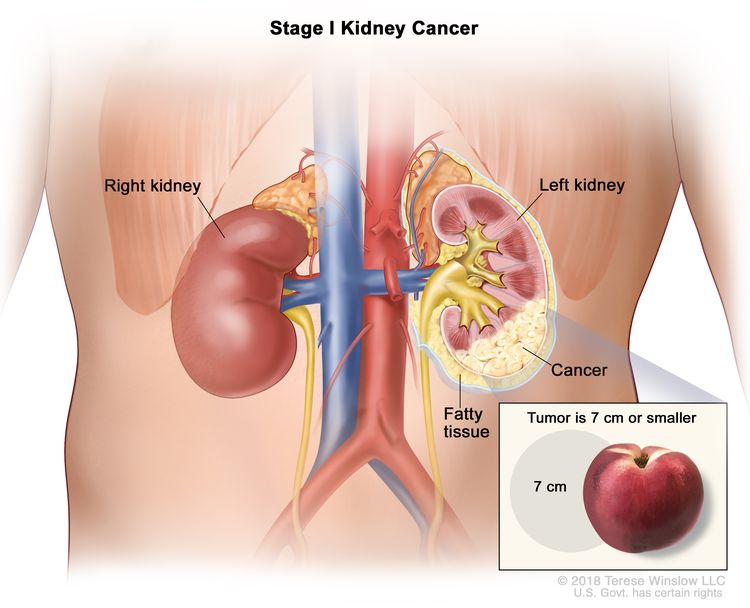

| I | T1, N0, M0 | T1 = Tumor ≤7 cm in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney. |

|

| –T1a = Tumor ≤4 cm in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney. | |||

| –T1b = Tumor >4 cm but ≤7 cm in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney. | |||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

| Stage | TNM | Definition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis. | |||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Kidney. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 739–48. | |||

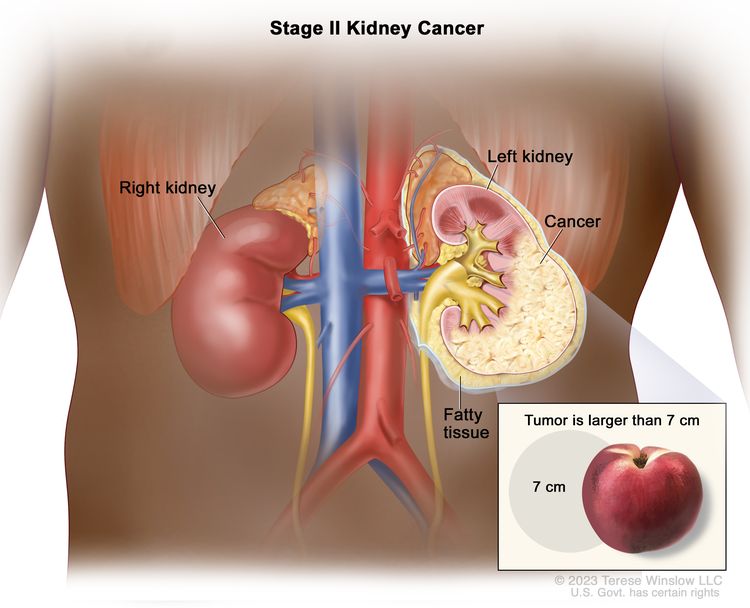

| II | T2, N0, M0 | T2 = Tumor >7 cm in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney. |

|

| –T2a = Tumor >7 cm but ≤10 cm in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney. | |||

| –T2b = Tumor >10 cm, limited to the kidney. | |||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

| Stage | TNM | Definition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis. | |||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Kidney. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 739–48. | |||

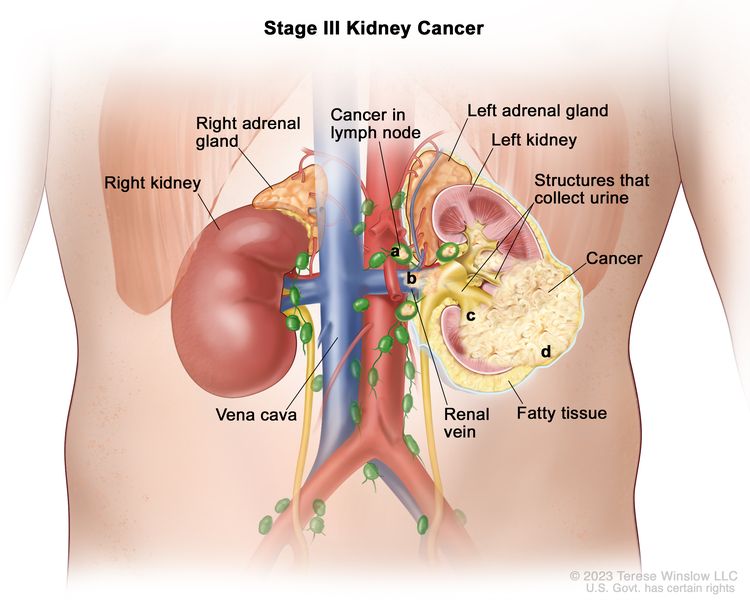

| III | T1, N1, M0 | T1 = Tumor ≤7 cm in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney. |

|

| –T1a = Tumor ≤4 cm in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney. | |||

| –T1b = Tumor >4 cm but ≤7 cm in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney. | |||

| N1 = Metastasis in regional lymph node(s). | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

| T2, N1, M0 | T2 = Tumor >7 cm in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney. | ||

| –T2a = Tumor >7 cm but ≤10 cm in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney. | |||

| –T2b = Tumor >10 cm, limited to the kidney. | |||

| N1 = Metastasis in regional lymph node(s). | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

| T3, N0, M0 | T3 = Tumor extends into major veins or perinephric tissues but not into the ipsilateral adrenal gland and not beyond Gerota's fascia. | ||

| –T3a = Tumor extends into the renal vein or its segmental branches, or invades the pelvicalyceal system, or invades perirenal and/or renal sinus fat but not beyond Gerota's fascia. | |||

| –T3b = Tumor extends into the vena cava below the diaphragm. | |||

| –T3c = Tumor extends into the vena cava above the diaphragm or invades the wall of the vena cava. | |||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

| T3, N1, M0 | T3 = Tumor extends into major veins or perinephric tissues but not into the ipsilateral adrenal gland and not beyond Gerota's fascia. | ||

| –T3a = Tumor extends into the renal vein or its segmental branches, or invades the pelvicalyceal system, or invades perirenal and/or renal sinus fat but not beyond Gerota's fascia. | |||

| –T3b = Tumor extends into the vena cava below the diaphragm. | |||

| –T3c = Tumor extends into the vena cava above the diaphragm or invades the wall of the vena cava. | |||

| N1 = Metastasis in regional lymph node(s). | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

| Stage | TNM | Definition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis. | |||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Kidney. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 739–48. | |||

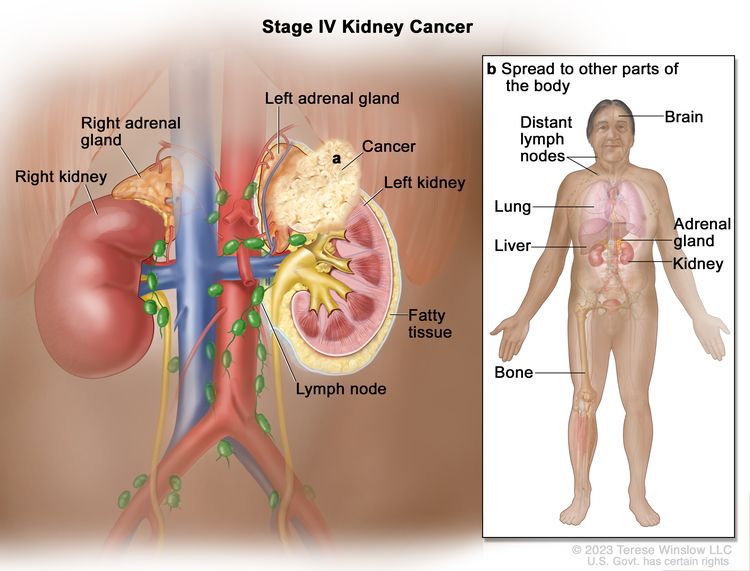

| IV | T4, Any N, M0 | T4 = Tumor invades beyond Gerota's fascia (including contiguous extension into the ipsilateral adrenal gland). |

|

| NX = Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed. | |||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||

| N1 = Metastasis in regional lymph node(s). | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||

| Any T, Any N, M1 | TX = Primary tumor cannot be assessed. | ||

| T0 = No evidence of primary tumor. | |||

| T1 = Tumor ≤7 cm in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney. | |||

| –T1a = Tumor ≤4 cm in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney. | |||

| –T1b = Tumor >4 cm but ≤7 cm in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney. | |||

| T2 = Tumor >7 cm in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney. | |||

| –T2a = Tumor >7 cm but ≤10 cm in greatest dimension, limited to the kidney. | |||

| –T2b = Tumor >10 cm, limited to the kidney. | |||

| T3 = Tumor extends into major veins or perinephric tissues but not into the ipsilateral adrenal gland and not beyond Gerota's fascia. | |||

| –T3a = Tumor extends into the renal vein or its segmental branches, or invades the pelvicalyceal system, or invades perirenal and/or renal sinus fat but not beyond Gerota's fascia. | |||

| –T3b = Tumor extends into the vena cava below the diaphragm. | |||

| –T3c = Tumor extends into the vena cava above the diaphragm or invades the wall of the vena cava. | |||

| T4 = Tumor invades beyond Gerota's fascia (including contiguous extension into the ipsilateral adrenal gland). | |||

| NX = Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed. | |||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||

| N1 = Metastasis in regional lymph node(s). | |||

| M1 = Distant metastasis. | |||

References

- Bassil B, Dosoretz DE, Prout GR: Validation of the tumor, nodes and metastasis classification of renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 134 (3): 450-4, 1985. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Golimbu M, Joshi P, Sperber A, et al.: Renal cell carcinoma: survival and prognostic factors. Urology 27 (4): 291-301, 1986. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Robson CJ, Churchill BM, Anderson W: The results of radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 101 (3): 297-301, 1969. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Consensus conference. Magnetic resonance imaging. JAMA 259 (14): 2132-8, 1988. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kidney. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp 739–48.

Treatment Option Overview for Renal Cell Cancer

Current treatment cures more than 50% of patients with stage I renal cell cancer, but patients with stage IV disease have poor outcomes. All patients with newly diagnosed renal cell cancer are candidates for clinical trials.

Treatment of Stage I Renal Cell Cancer

Treatment Options for Stage I Renal Cell Cancer

Treatment options for stage I renal cell cancer include:

- Partial nephrectomy (selected patients).[1,2]

- Radical nephrectomy.[2]

- Simple nephrectomy.[2]

- Cryotherapy.

- Thermal ablation.

- Stereotactic ablative body radiation therapy (SABR or SBRT) (also referred to as stereotactic radiosurgery).

- External-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) (palliative).[2]

- Arterial embolization (palliative).[2,3]

- Clinical trials.

Surgical resection is the accepted, often curative therapy for patients with stage I renal cell cancer. In appropriately selected patients, partial nephrectomy has oncologic outcomes that are comparable with those of radical nephrectomy. Partial nephrectomy also has the benefits of preserving greater renal function and, according to some studies, reduced mortality.[4-7] When the entire kidney is removed, resection may be simple or radical. Radical resection includes removal of the kidney, adrenal gland, perirenal fat, and Gerota's fascia, with or without a regional lymph node dissection. Radical nephrectomy is preferred if the tumor extends into the inferior vena cava.

In patients with bilateral stage I neoplasms (concurrent or subsequent), bilateral partial nephrectomy or unilateral partial nephrectomy with contralateral radical nephrectomy, when technically feasible, may be a preferred alternative to bilateral nephrectomy with dialysis or transplant.[1] Increasing evidence suggests that a partial nephrectomy is curative in selected cases. A pathologist should examine the gross specimen as well as the frozen section from the parenchymal margin of excision.[8]

In patients who are not candidates for resection, there are several curative alternatives, including cryoablation, thermal ablation, and SABR (or SBRT).[9-13]

In patients who are not candidates for the treatments above, EBRT or arterial embolization can provide palliation.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Novick AC, Streem S, Montie JE, et al.: Conservative surgery for renal cell carcinoma: a single-center experience with 100 patients. J Urol 141 (4): 835-9, 1989. [PUBMED Abstract]

- deKernion JB, Berry D: The diagnosis and treatment of renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 45 (7 Suppl): 1947-56, 1980. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Swanson DA, Wallace S, Johnson DE: The role of embolization and nephrectomy in the treatment of metastatic renal carcinoma. Urol Clin North Am 7 (3): 719-30, 1980. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kim SP, Thompson RH, Boorjian SA, et al.: Comparative effectiveness for survival and renal function of partial and radical nephrectomy for localized renal tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol 188 (1): 51-7, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Larcher A, Capitanio U, Terrone C, et al.: Elective Nephron Sparing Surgery Decreases Other Cause Mortality Relative to Radical Nephrectomy Only in Specific Subgroups of Patients with Renal Cell Carcinoma. J Urol 196 (4): 1008-13, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wang Z, Wang G, Xia Q, et al.: Partial nephrectomy vs. radical nephrectomy for renal tumors: A meta-analysis of renal function and cardiovascular outcomes. Urol Oncol 34 (12): 533.e11-533.e19, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Patel HD, Pierorazio PM, Johnson MH, et al.: Renal Functional Outcomes after Surgery, Ablation, and Active Surveillance of Localized Renal Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12 (7): 1057-1069, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Thrasher JB, Robertson JE, Paulson DF: Expanding indications for conservative renal surgery in renal cell carcinoma. Urology 43 (2): 160-8, 1994. [PUBMED Abstract]

- El Dib R, Touma NJ, Kapoor A: Cryoablation vs radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis of case series studies. BJU Int 110 (4): 510-6, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gkentzis A, Oades G: Thermal ablative therapies for treatment of localised renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review of the literature. Scott Med J 61 (4): 185-191, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Zargar H, Atwell TD, Cadeddu JA, et al.: Cryoablation for Small Renal Masses: Selection Criteria, Complications, and Functional and Oncologic Results. Eur Urol 69 (1): 116-28, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Salagierski M, Wojciechowska A, Zając K, et al.: The Role of Ablation and Minimally Invasive Techniques in the Management of Small Renal Masses. Eur Urol Oncol 1 (5): 395-402, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Siva S, Ali M, Correa RJM, et al.: 5-year outcomes after stereotactic ablative body radiotherapy for primary renal cell carcinoma: an individual patient data meta-analysis from IROCK (the International Radiosurgery Consortium of the Kidney). Lancet Oncol 23 (12): 1508-1516, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Stage II Renal Cell Cancer

Treatment Options for Stage II Renal Cell Cancer

Treatment options for stage II renal cell cancer include:

- Partial nephrectomy (selected patients).[1]

- Radical nephrectomy.[1]

- Radical nephrectomy followed by adjuvant pembrolizumab (high-risk patients).[2]

- Nephrectomy before or after external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) (selected patients).[1]

- EBRT (palliative).[1]

- Arterial embolization (palliative).

- Clinical trials.

Surgical resection is the accepted, often curative, therapy for patients with stage II renal cell cancer. In appropriately selected patients, partial nephrectomy has oncologic outcomes that are comparable with those of radical nephrectomy. Partial nephrectomy also has the benefits of preserving greater renal function and, according to some studies, reduced mortality.[3-6] When the entire kidney is removed, resection may be simple or radical. Radical resection includes removal of the kidney, adrenal gland, perirenal fat, and Gerota's fascia, with or without a regional lymph node dissection. Radical nephrectomy is preferred if the tumor extends into the inferior vena cava. Lymphadenectomy is commonly used, but its effectiveness has not been definitively proven.

Postoperative systemic therapy with the anti-programmed death-1 (PD-1) antibody pembrolizumab has been shown to prolong disease-free survival (DFS), but not overall survival (OS), in patients with high-risk pT2 tumors.

In patients who are not candidates for surgery, arterial embolization can provide palliation.

Adjuvant pembrolizumab

Pembrolizumab is an immune checkpoint inhibitor and a monoclonal antibody targeting the PD-1 protein.

Evidence (adjuvant pembrolizumab):

- A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (KEYNOTE-564 [NCT03142334]) studied the impact of 1 year of pembrolizumab after nephrectomy. The study enrolled 994 patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma at high risk of recurrence after nephrectomy. Eligibility included patients with stage II disease with nuclear grade 4 or sarcomatoid differentiation, stage III disease or higher, regional lymph node metastases, or stage M1 status with no evidence of disease after resection. Patients were randomly assigned to receive up to 12 months of pembrolizumab (200 mg) or placebo administered intravenously every 21 days. The primary end point was DFS.[2]

- At a median follow-up of 24 months, pembrolizumab was associated with a higher 2-year DFS rate than placebo (77.3% for pembrolizumab vs. 68.1% for placebo; hazard ratio [HR], 0.68; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.53–0.87).[2][Level of evidence B1] A subsequent report with a median follow-up of 30 months showed a 75.2% DFS rate for patients who received pembrolizumab, compared with 65.5% for patients who received placebo (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.50–0.80).[7]

- Grade 3 or higher adverse events were reported for 32% of patients who received pembrolizumab, and 20% of the patients had serious adverse events. The most common high-grade adverse events were diarrhea and transaminitis, each occurring in 2% of patients who received pembrolizumab. The most common serious adverse events were adrenal insufficiency, colitis, and diabetic ketoacidosis, each occurring in 1% of patients who received pembrolizumab.

- OS (the secondary end point) will be assessed when the study has longer follow-up.

Questions have been raised about confounding issues that may have resulted in the significant improvement in DFS in the KEYNOTE-564 trial.[8] An uneven number of patients dropped out in the early follow-up period, which led to a lack of information about recurrence in the control group for the censored patients. Only 36% of the 166 patients in the control group received immunotherapy at relapse, despite conclusive evidence for an OS advantage when immunotherapy is given to patients with metastatic disease. Two other trials using atezolizumab or nivolumab plus ipilimumab failed to show a significant difference in DFS or OS.[9,10] These issues suggest that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of pembrolizumab in the adjuvant setting, and the guidelines released by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the European Society for Medical Oncology may have been premature. Further follow-up for more mature DFS and especially OS results is needed.[8,11]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- deKernion JB, Berry D: The diagnosis and treatment of renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 45 (7 Suppl): 1947-56, 1980. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Choueiri TK, Tomczak P, Park SH, et al.: Adjuvant Pembrolizumab after Nephrectomy in Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 385 (8): 683-694, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kim SP, Thompson RH, Boorjian SA, et al.: Comparative effectiveness for survival and renal function of partial and radical nephrectomy for localized renal tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol 188 (1): 51-7, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Larcher A, Capitanio U, Terrone C, et al.: Elective Nephron Sparing Surgery Decreases Other Cause Mortality Relative to Radical Nephrectomy Only in Specific Subgroups of Patients with Renal Cell Carcinoma. J Urol 196 (4): 1008-13, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wang Z, Wang G, Xia Q, et al.: Partial nephrectomy vs. radical nephrectomy for renal tumors: A meta-analysis of renal function and cardiovascular outcomes. Urol Oncol 34 (12): 533.e11-533.e19, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Patel HD, Pierorazio PM, Johnson MH, et al.: Renal Functional Outcomes after Surgery, Ablation, and Active Surveillance of Localized Renal Tumors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12 (7): 1057-1069, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Powles T, Tomczak P, Park SH, et al.: Pembrolizumab versus placebo as post-nephrectomy adjuvant therapy for clear cell renal cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-564): 30-month follow-up analysis of a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 23 (9): 1133-1144, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tannock IF, Goldstein DA, Ofer J, et al.: Evaluating Trials of Adjuvant Therapy: Is There Benefit for People With Resected Renal Cancer? J Clin Oncol 41 (15): 2713-2717, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Pal SK, Uzzo R, Karam JA, et al.: Adjuvant atezolizumab versus placebo for patients with renal cell carcinoma at increased risk of recurrence following resection (IMmotion010): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 400 (10358): 1103-1116, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Motzer RJ, Russo P, Grünwald V, et al.: Adjuvant nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus placebo for localised renal cell carcinoma after nephrectomy (CheckMate 914): a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 401 (10379): 821-832, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Merino M, Kasamon Y, Theoret M, et al.: Irreconcilable Differences: The Divorce Between Response Rates, Progression-Free Survival, and Overall Survival. J Clin Oncol 41 (15): 2706-2712, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Stage III Renal Cell Cancer

Treatment Options for Stage III Renal Cell Cancer

Treatment options for stage III renal cell cancer include:

- Radical nephrectomy.[1]

- Preoperative embolization and radical nephrectomy.[2,3]

- Radical nephrectomy followed by adjuvant systemic therapy with pembrolizumab or sunitinib.[4,5]

- External-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) (palliative).[2]

- Tumor embolization (palliative).[3]

- Palliative nephrectomy.

- Preoperative or postoperative EBRT and radical nephrectomy.[2]

- Clinical trials involving adjuvant interferon alfa.

Adjuvant systemic therapy

Surgical resection is the standard treatment for patients with clinical stage III renal cell cancer. Several different studies have investigated whether adjuvant (postoperative) systemic therapy improves outcomes. None of these trials have demonstrated any impact on overall survival (OS). However, two agents are associated with longer relapse-free survival.

Adjuvant pembrolizumab

Pembrolizumab is an immune checkpoint inhibitor and a monoclonal antibody targeting the programmed death-1 (PD-1) protein.

Evidence (adjuvant pembrolizumab):

- A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (KEYNOTE-564 [NCT03142334]) studied the impact of 1 year of pembrolizumab after nephrectomy. The study enrolled 994 patients with clear cell renal cell cancer at high risk of recurrence after nephrectomy. Eligibility included patients with stage II disease with nuclear grade 4 or sarcomatoid differentiation, stage III disease or higher, regional lymph node metastases, or stage M1 status with no evidence of disease after resection. Patients were randomly assigned to receive up to 12 months of pembrolizumab (200 mg) or placebo administered intravenously every 21 days. The primary end point was disease-free survival (DFS).[4]

- At a median follow-up of 24 months, pembrolizumab was associated with a higher 2-year DFS rate than placebo (77.3% for pembrolizumab vs. 68.1% for placebo; hazard ratio [HR], 0.68; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.53–0.87).[4][Level of evidence B1] A subsequent report with a median follow-up of 30 months showed a 75.2% DFS rate for patients who received pembrolizumab, compared with 65.5% for patients who received placebo (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.50–0.80).[6]

- Grade 3 or higher adverse events were reported for 32% of patients who received pembrolizumab, and 20% of the patients had serious adverse events. The most common high-grade adverse events were diarrhea and transaminitis, each occurring in 2% of patients who received pembrolizumab. The most common serious adverse events were adrenal insufficiency, colitis, and diabetic ketoacidosis, each occurring in 1% of patients who received pembrolizumab.

- OS (the secondary end point) will be assessed when the study has longer follow-up.

Questions have been raised about confounding issues that may have resulted in the significant improvement in DFS in the KEYNOTE-564 trial.[7] An uneven number of patients dropped out in the early follow-up period, which led to a lack of information about recurrence in the control group for the censored patients. Only 36% of the 166 patients in the control group received immunotherapy at relapse, despite conclusive evidence for an OS advantage when immunotherapy is given to patients with metastatic disease. Two other trials using atezolizumab or nivolumab plus ipilimumab failed to show a significant difference in DFS or OS.[8,9] These issues suggest that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval of pembrolizumab in the adjuvant setting, and the guidelines released by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and the European Society for Medical Oncology may have been premature. Further follow-up for more mature DFS and especially OS results is needed.[7,10]

Adjuvant sunitinib

Sunitinib is an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting the vascular endothelial growth factor pathway.

Evidence (sunitinib):

- A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial (NCT00375674) studied the impact of sunitinib after nephrectomy in patients with locoregional, high-risk, clear cell renal cell cancer (stage T3 or higher and/or regional lymph node metastases). The study randomly assigned 615 patients to receive either 1 year of sunitinib (50 mg) or placebo once daily for the first 4 weeks of a repeating 6-week cycle (i.e., a 4-week-on, 2-week-off schedule).[5]

- The median DFS was 6.8 years for patients who received sunitinib and 5.6 years for patients who received placebo (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.59–0.98; P = .03). No difference in OS was reported (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.72–1.44; P = .94).

- Dose reductions were reported in 34% of patients who received sunitinib. Dose interruptions were seen in 46% of patients, and 28% of patients assigned to sunitinib discontinued the medication.

- Of patients who received sunitinib, 48% experienced grade 3 adverse events and 12% experienced grade 4 adverse events. The most common high-grade adverse events were palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, hypertension, fatigue, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and mucosal inflammation.

Treatment options for patients with T3a, N0, M0 disease

Radical resection is the accepted, often curative therapy for patients with this stage of renal cell cancer. The operation includes removal of the kidney, adrenal gland, perirenal fat, and Gerota's fascia, with or without a regional lymph node dissection.[11] Lymphadenectomy is commonly used, but its effectiveness has not been definitively proven. EBRT has been given before or after nephrectomy, without conclusive evidence that it improves survival compared with the results of surgery alone. However, it may benefit selected patients with more extensive tumors.

In patients with bilateral stage T3a neoplasms (concurrent or subsequent), bilateral partial nephrectomy or unilateral partial nephrectomy with contralateral radical nephrectomy, when technically feasible, may be a preferred alternative to bilateral nephrectomy with dialysis or transplant.[12]

In patients who are not candidates for surgery, arterial embolization can provide palliation.

Treatment options for patients with T3b, N0, M0 disease

Radical resection is the accepted, often curative therapy for patients with this stage of renal cell cancer. The operation includes removal of the kidney, adrenal gland, perirenal fat, and Gerota's fascia, with or without a regional lymph node dissection.[11] Lymphadenectomy is commonly used, but its effectiveness has not been definitively proven. Surgery is extended to remove the entire renal vein and caval thrombus and a portion of the vena cava as necessary.[1] EBRT has been given before or after nephrectomy, without conclusive evidence that it improves survival compared with the results of surgery alone. However, it may benefit selected patients with more extensive tumors.

In patients with stage T3b neoplasms who manifest concurrent or subsequent renal cell cancer in the contralateral kidney, a partial nephrectomy, when technically feasible, may be a preferred alternative to bilateral nephrectomy with dialysis or transplant.[12-14]

In patients who are not candidates for surgery, arterial embolization can provide palliation.

Treatment options for patients with T1, N1, M0; T2, N1, M0; or T3, N1, M0 disease

This stage of renal cell cancer is curable with surgery in a small minority of patients. A radical nephrectomy and lymph node dissection is necessary. The value of preoperative and postoperative EBRT has not been demonstrated, but EBRT may be used for palliation in patients who are not candidates for surgery. Arterial embolization of the tumor with Gelfoam or other materials may be used preoperatively to reduce blood loss at nephrectomy or for palliation in patients with inoperable disease.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Hatcher PA, Anderson EE, Paulson DF, et al.: Surgical management and prognosis of renal cell carcinoma invading the vena cava. J Urol 145 (1): 20-3; discussion 23-4, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

- deKernion JB, Berry D: The diagnosis and treatment of renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 45 (7 Suppl): 1947-56, 1980. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Swanson DA, Wallace S, Johnson DE: The role of embolization and nephrectomy in the treatment of metastatic renal carcinoma. Urol Clin North Am 7 (3): 719-30, 1980. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Choueiri TK, Tomczak P, Park SH, et al.: Adjuvant Pembrolizumab after Nephrectomy in Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 385 (8): 683-694, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ravaud A, Motzer RJ, Pandha HS, et al.: Adjuvant Sunitinib in High-Risk Renal-Cell Carcinoma after Nephrectomy. N Engl J Med 375 (23): 2246-2254, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Powles T, Tomczak P, Park SH, et al.: Pembrolizumab versus placebo as post-nephrectomy adjuvant therapy for clear cell renal cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-564): 30-month follow-up analysis of a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 23 (9): 1133-1144, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tannock IF, Goldstein DA, Ofer J, et al.: Evaluating Trials of Adjuvant Therapy: Is There Benefit for People With Resected Renal Cancer? J Clin Oncol 41 (15): 2713-2717, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Pal SK, Uzzo R, Karam JA, et al.: Adjuvant atezolizumab versus placebo for patients with renal cell carcinoma at increased risk of recurrence following resection (IMmotion010): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 400 (10358): 1103-1116, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Motzer RJ, Russo P, Grünwald V, et al.: Adjuvant nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus placebo for localised renal cell carcinoma after nephrectomy (CheckMate 914): a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 401 (10379): 821-832, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Merino M, Kasamon Y, Theoret M, et al.: Irreconcilable Differences: The Divorce Between Response Rates, Progression-Free Survival, and Overall Survival. J Clin Oncol 41 (15): 2706-2712, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Phillips E, Messing EM: Role of lymphadenectomy in the treatment of renal cell carcinoma. Urology 41 (1): 9-15, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Novick AC, Streem S, Montie JE, et al.: Conservative surgery for renal cell carcinoma: a single-center experience with 100 patients. J Urol 141 (4): 835-9, 1989. [PUBMED Abstract]

- deKernion JB: Management of renal adenocarcinoma. In: deKernion JB, Paulson DF, eds.: Genitourinary Cancer Management. Lea and Febiger, 1987, pp 187-217.

- Angermeier KW, Novick AC, Streem SB, et al.: Nephron-sparing surgery for renal cell carcinoma with venous involvement. J Urol 144 (6): 1352-5, 1990. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Stage IV and Recurrent Renal Cell Cancer

Treatment Options for First-Line Therapy for Stage IV Renal Cell Cancer

Treatment options for first-line therapy for stage IV renal cell cancer include:

- Ipilimumab plus nivolumab (for patients with intermediate or poor-risk disease).[1]

- Pembrolizumab plus axitinib.[2]

- Pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib.[3]

- Nivolumab plus cabozantinib.[4]

- Radical nephrectomy (for T4, M0 lesions).

- Cytoreductive nephrectomy (for any T, M1 lesions in patients with good-risk disease).[5-8]

- Cabozantinib (for patients with intermediate- or poor-risk disease).[9,10]

- Avelumab plus axitinib.[11]

- Sunitinib.[12-15]

- Interferon alfa.[16-19]

- Interleukin-2 (IL-2).[16,20,21]

- Palliative external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT).

Treatment Options for Second-Line Therapy for Stage IV Renal Cell Cancer

Treatment options for second-line therapy for stage IV renal cell cancer include:

- Nivolumab (for patients previously treated with sunitinib, pazopanib, sorafenib, and/or axitinib).[22]

- Lenvatinib plus everolimus (for patients previously treated with sunitinib, pazopanib, cabozantinib, axitinib, or sorafenib).[23]

- Cabozantinib (for patients previously treated with sunitinib, pazopanib, sorafenib, or axitinib).[24]

- Belzutifan.[25]

- Palliative EBRT.

Treatment Options for Third- and Fourth-Line Therapy for Stage IV Renal Cell Cancer

Treatment options for third- and fourth-line therapy for stage IV renal cell cancer include:

The prognosis is poor for any patient with renal cell cancer that is progressing, recurring, or relapsing after treatment, regardless of cancer cell type or stage of disease. Almost all patients with stage IV renal cell cancer have incurable disease. The use and selection of further treatment depends on many factors, including previous treatment and site of recurrence, as well as individual patient considerations. Carefully selected patients may benefit from surgical resection of localized metastatic disease, particularly if they have had a prolonged disease-free interval since their primary therapy.

Immunotherapy

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

Immune checkpoint inhibitors are drugs that block certain proteins that inhibit the immune system's response to cancer. These proteins down-regulate T-lymphocyte activity and can prevent these cells from killing cancer cells. By reducing the activity of these inhibitory proteins, immune checkpoint inhibitors increase the immune response to cancer. Immune checkpoint proteins that are targeted by this class of drugs include programmed death-1 (PD-1), programmed cell death-ligand-1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4).

Ipilimumab plus nivolumab

In a randomized controlled trial, the combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab prolonged overall survival (OS) when compared with sunitinib as first-line systemic therapy for patients with advanced-stage renal cell carcinoma.[1] Both drugs are immune checkpoint inhibitors. Ipilimumab is an antibody that targets CTLA-4. Nivolumab is an antibody that targets PD-1.

Evidence (ipilimumab plus nivolumab):

- A randomized controlled trial compared the combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab with sunitinib. Nivolumab (3 mg/kg) and ipilimumab (1 mg/kg) were given every 3 weeks for four doses, followed by maintenance nivolumab (3 mg/kg) every 2 weeks. Sunitinib was given at a dose of 50 mg once daily for the first 4 weeks of a repeating 6-week cycle (i.e., each cycle consisted of 4 weeks taking the drug, followed by a 2-week break). Treatment continued until disease progression unless adverse events or withdrawal of consent led to discontinuation. The coprimary end points were OS, progression-free survival (PFS), and objective response rate in patients with intermediate- or poor-risk disease. Of note, because there were three primary end points, the overall alpha level of 0.05 was divided among the three end points. This meant that the P-value cutoffs for significance were 0.001 for response rate, 0.009 for PFS, and 0.04 for OS. The trial enrolled 1,096 patients, 847 of whom had intermediate- or poor-risk disease.

- With a median follow-up of 25.2 months for intermediate- and poor-risk patients, the 18-month OS rate was 75% in the ipilimumab-plus-nivolumab arm, compared with 60% in the sunitinib arm. Among patients with intermediate- and poor-risk disease, the hazard ratio (HR)death was 0.63 (99.8% confidence interval [CI], 0.44–0.89; P < .001).

- There was no statistically significant difference in PFS. Median PFS among patients with intermediate- and poor-risk disease was 11.6 months with ipilimumab plus nivolumab, compared with 8.4 months with sunitinib (HR, 0.82; 99.1% CI, 0.64–1.05).

- The objective response rate was higher with ipilimumab plus nivolumab than with sunitinib (42% vs. 27%, P < .001). In the ipilimumab-plus-nivolumab arm, 40 patients (9%) had complete responses, compared with 5 patients (1%) in the sunitinib arm.

Nivolumab

Nivolumab is the only treatment that has shown prolonged OS in patients who have previously received antiangiogenic therapy. Nivolumab is a fully human antibody that blocks ligand activation of the PD-1 protein. By blocking the interaction between PD-1 and PD-1 ligands 1 and 2, nivolumab blocks a pathway that inhibits the cellular immune response and restores cellular immunity.

Evidence (nivolumab):

- A phase II trial showed promising results and no dose response with nivolumab, which was given every 3 weeks at a dose of 0.3 mg/kg, 2 mg/kg, or 10 mg/kg.[22]

- The median survival was 25.5 months with a dose of 2 mg/kg given every 3 weeks and 24.7 months with a dose of 10 mg/kg given every 3 weeks.

- A randomized controlled trial compared nivolumab at a dose of 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks with everolimus at a dose of 10 mg daily.[38] The trial randomly assigned 821 patients with metastatic renal cell cancer and a clear cell component who had previously received one or two antiangiogenic regimens.

- The objective response rate was 25% with nivolumab, compared with 5% with everolimus (P < .001).

- The median duration of treatment was 5.5 months with nivolumab, compared with 3.7 months with everolimus, and there was no significant difference in PFS (median PFS, 4.6 months with nivolumab vs. 4.4 months with everolimus).

- However, OS was significantly longer with nivolumab (median OS, 25.0 months vs. 19.6 months; HR, 0.73; 98.5% CI, 0.57–0.93).[38]

It is not clear whether the dose of 3 mg/kg every 2 weeks used in the phase III trial offers any advantage over the dose of 2 mg/kg every 3 weeks used in the phase II trial. However, the latter dose offers substantial cost savings.

Cytokine therapy

Interferon alfa and IL-2

Cytokine therapy with interferon alfa or IL-2 has been shown to induce objective responses. Interferon alfa appears to have a modest impact on survival in selected patients. Interferon alfa has approximately a 15% objective response rate in appropriately selected individuals.[16] In general, these patients have nonbulky pulmonary or soft tissue metastases with excellent performance status ratings of 0 or 1, according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) rating scale, and the patients show no weight loss. The interferon alfa doses used in studies reporting good response rates have been in an intermediate range (6–20 million units administered 3 times weekly). A Cochrane analysis of six randomized trials, with a total of 963 patients, indicated an HR for survival of 0.78 (0.67–0.90) or a weighted average improvement in survival of 2.6 months.[16][Level of evidence A1]

High-dose IL-2 produces an overall response rate similar to that of interferon alfa, but approximately 5% of the patients have shown durable complete remissions.[20,39-43] No randomized controlled trial of IL-2 has shown a longer survival result. High-dose IL-2 is used because it is the only systemic therapy that has been associated with inducing durable complete remissions, albeit in a small fraction (about 5%) of patients who are eligible for this treatment. The optimum dose of IL-2 is unknown. High-dose therapy appears to be associated with higher response rates but with more toxic effects. Low-dose inpatient regimens show activity against renal cell carcinoma with fewer toxic effects, especially hypotension, but have not been shown to be superior to placebo or any alternative regimen in terms of survival or quality of life (QOL).[21] Outpatient subcutaneous administration has also demonstrated responses with acceptable toxic effects but, again, with unclear survival or QOL benefit.[44] Combinations of IL-2 and interferon alfa have been studied, but outcomes have not been better than with high-dose or low-dose IL-2 alone.[17,45]

Combined Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Antiangiogenic Targeted Therapies

After immune checkpoint inhibitors and antiangiogenic targeted therapies were found to improve outcomes, clinical trials of the combination of these two approaches showed longer OS when compared with monotherapy.

Pembrolizumab plus axitinib

Evidence (pembrolizumab plus axitinib):

- An open-label, phase III, randomized controlled trial (NCT02853331) compared sunitinib with the combination of pembrolizumab and axitinib. The study enrolled 861 patients who had received no previous systemic therapy for metastatic disease.[2]

- With median follow-up of 12.8 months, the 1-year OS rate was 90% in the pembrolizumab-plus-axitinib arm, compared with 78% in the sunitinib arm (HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.38–0.74; P < .0001).[2][Level of evidence A1]

- Median PFS was also prolonged for patients who received the combination therapy (15.1 months vs. 11.1 months; HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.57–0.84).

- The objective response rate was 59.3% for patients who received combination therapy, compared with 35.7% for patients who received sunitinib (P < .001).

- Grade 3 or higher adverse event rates were similar: 75.8% of the patients in the pembrolizumab-plus-axitinib arm, compared with 70.6% of the patients in the sunitinib arm.

Pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib

Evidence (pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib):

- An open-label, phase III, randomized controlled trial (NCT02811861) compared sunitinib with either lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab or lenvatinib plus everolimus. The study enrolled 1,609 patients who had received no previous systemic therapy for metastatic disease.[3]

- With a median follow-up of 26.6 months, the 2-year OS rate was 79.2% in the pembrolizumab-plus-lenvatinib arm, compared with 70.4% in the sunitinib arm (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.49–0.88; P = .005).[3][Level of evidence A1] There was no difference in OS between the sunitinib and lenvatinib-plus-everolimus arms.

- The median PFS was also longer with pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib than with sunitinib (23.9 months vs. 9.2 months; HR, 0.39; 95% CI, 0.32–0.49; P < .001). The PFS was also longer in the lenvatinib-plus-everolimus arm (14.7 months), compared with the sunitinib arm (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.53–0.80; P < .001).

- The objective response rate was 71.0% with pembrolizumab-plus-lenvatinib therapy, compared with 36.1% with sunitinib (P < .001). Complete responses were reported in 16.1% of patients in the pembrolizumab-plus-lenvatinib arm, 4.2% of patients in the sunitinib arm, and 9.8% of patients in the lenvatinib-plus-everolimus arm.

- Grade 3 or higher adverse event rates were more common in the lenvatinib arms: 82.4% of the patients in the pembrolizumab-plus-lenvatinib arm and 83.1% of patients in the lenvatinib-plus-everolimus arm, compared with 71.8% of patients in the sunitinib arm. Treatment was discontinued in 37.2% of patients in the pembrolizumab-plus-lenvatinib arm, compared with 14.4% of patients in the sunitinib arm. Hypertension (27.6%), diarrhea (9.7%), and weight loss (8.0%) were the most common high-grade toxicities in the pembrolizumab-plus-lenvatinib arm.

- Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) was assessed using multiple measures. The results showed that patients who received pembrolizumab and lenvatinib had similar or less deterioration of their HRQOL and disease-related symptom scores over time when compared with patients who received sunitinib.[46][Level of evidence B2]

Nivolumab plus cabozantinib

Evidence (nivolumab plus cabozantinib):

- An open-label, phase III, randomized controlled trial (NCT03141177) compared sunitinib with nivolumab plus cabozantinib. The study enrolled 651 patients who had received no previous systemic therapy for metastatic disease.[47]

- With a median follow-up of 32.9 months, the OS was 37.7 months in the nivolumab-plus-cabozantinib arm, compared with 34.3 months in the sunitinib arm (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.55–0.90).[47][Level of evidence A1]

- The median PFS was also longer in the nivolumab-plus-cabozantinib arm than in the sunitinib arm (16.6 months vs. 8.3 months; HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.41–0.64; P < .001).

- The objective response rate was 55.7% for patients who received combination therapy, compared with 27.1% for patients who received sunitinib (P < .001).

- Grade 3 or higher adverse event rates were reported in 65% of patients who received nivolumab plus cabozantinib, compared with 54% of those who received sunitinib. High-grade treatment-related serious adverse events were reported in 22% of patients in the combination therapy arm and 10% of patients in the sunitinib arm. At least one of the trial drugs was discontinued in 19.7% of those assigned to combination therapy, compared with 16.9% of those assigned to sunitinib. The most common high-grade toxicities with combination therapy were hypertension (12.5%), hyponatremia (9.4%), diarrhea (6.9%), elevated lipase (6.2%), and hypophosphatemia (5.9%).

Avelumab plus axitinib

Evidence (avelumab plus axitinib):

- An open-label, phase III, randomized trial (NCT02684006) compared the combination of avelumab and axitinib with sunitinib monotherapy. The study included 560 patients with previously untreated stage IV PD-L1–positive renal cell carcinoma (the entire study population was 886 patients, including those who were PD-L1 negative).[11] This trial specified two primary end points: PFS and OS among patients with PD-L1-positive tumors. PFS among the entire study population was a secondary end point.

- With a median follow-up of less than 1 year, there was no significant difference in OS between the two arms.

- Among patients with PD-L1–positive tumors, the PFS was 13.8 months in the combination therapy arm, compared with 7.2 months in the sunitinib arm (HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.47–0.79).[11][Level of evidence B1]

- For the entire study population, the median PFS was 13.8 months in the combination arm, compared with 8.4 months in the sunitinib arm (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.56–0.84).

Local Therapy

In patients without metastatic disease, resection of the primary tumor, when feasible, is standard practice. In patients with unresectable and/or metastatic cancers, tumor embolization, EBRT, and nephrectomy can aid in the palliation of symptoms caused by the primary tumor or related ectopic hormone or cytokine production.

Cytoreductive nephrectomy

In the era before targeted antiangiogenic therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors, two randomized studies demonstrated an OS benefit in selected patients who underwent initial cytoreductive nephrectomy before the administration of interferon alfa.[5,6] However, there is evidence that undergoing cytoreductive nephrectomy before antiangiogenic therapy does not provide a survival benefit to patients with intermediate- and poor-risk disease. Cytoreductive nephrectomy for good-risk patients has not been studied in a randomized controlled trial in the era of targeted therapies and immunotherapy. The limited data available from retrospective nonrandomized studies suggest a benefit in good-risk patients in the current era of targeted therapies.

The CARMENA trial (NCT00930033) evaluated the effectiveness of cytoreductive nephrectomy before targeted therapy. The study reported no benefit for patients who underwent cytoreductive nephrectomy before receiving treatment with sunitinib, an oral antiangiogenic tyrosine kinase inhibitor.[7] This study enrolled only patients with intermediate- (57%) and poor-risk (43%) disease, whereas a previous retrospective study found that cytoreductive nephrectomy only benefited good- and intermediate-risk patients in the sunitinib era. Similarly, the positive trials in the interferon era were restricted to patients who were asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic, with a performance status rating of 0 or 1, according to the ECOG rating scale; these patients were also considered candidates for postoperative immunotherapy.

A multicenter analysis of 351 patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma was conducted to assess the impact of cytoreductive nephrectomy. The study evaluated patients who received systemic therapy and compared outcomes of those who underwent cytoreductive nephrectomy with those who did not. The median OS was 38.1 months for patients who underwent nephrectomy compared with 16.4 months for those treated with systemic therapy alone (P = .03). However, the survival benefit was limited to patients with an ECOG performance status rating of 0 to 1 and good- or intermediate-risk disease.[8] Interpretation of the study is limited by selection bias because patients were not randomly assigned to the nephrectomy group. Whether there is a benefit from cytoreductive nephrectomy for patients who are not subsequently treated with systemic therapy has not been tested.

Randomized controlled trials of cytoreductive nephrectomy:

A randomized, controlled, noninferiority trial of 450 patients compared the outcomes of patients who received sunitinib alone with those who received cytoreductive nephrectomy followed by sunitinib. The trial was designed to enroll 576 individuals; therefore it was underpowered.[7] In this study, 43% of the patients had poor-risk disease and 57% had intermediate-risk disease.

- With a median follow-up of 50.9 months, and after 326 deaths, the HRdeath was 0.89 (95% CI, 0.71–1.10) in favor of sunitinib alone. The median OS was 18.4 months in the sunitinib-alone arm and 13.9 months in the nephrectomy-followed-by-sunitinib arm, but the difference was not statistically significant.[7][Level of evidence A1]

Randomized controlled trials of interferon with or without preceding cytoreductive nephrectomy:

Two randomized studies demonstrated an OS benefit in selected patients who underwent initial cytoreductive nephrectomy before the administration of interferon alfa.[5,6]

- In the larger study, 246 patients were randomly assigned to either undergo a nephrectomy followed by interferon alfa or receive interferon alfa alone.[5]

- The median OS was 11.1 months when the primary tumor was removed first (95% CI, 9.2–16.5), compared with 8.1 months in the control arm (95% CI, 5.4–9.5; P = .05).

- In the smaller study, 85 patients with identical eligibility criteria were randomly assigned to treatment as in the larger study.[6]

- Patients who underwent nephrectomy before receiving interferon alfa had a median OS of 17 months compared with an OS of 7 months in patients who received interferon alfa alone (HR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.31–0.94; P = .03).[6][Level of evidence A1]

Resection of oligometastatic disease

Selected patients with solitary or a limited number of distant metastases can achieve prolonged survival with nephrectomy and surgical resection of the metastases.[48-53] Even patients with brain metastases had similar results.[54] The likelihood of achieving therapeutic benefit with this approach appears enhanced in patients with a long disease-free interval between the initial nephrectomy and the development of metastatic disease.

Antiangiogenic and Other Targeted Therapy

A growing understanding of the biology of cancer in general, and renal cell cancer in particular, has led to the development and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of six new agents that target specific growth pathways. Two of the approved targeted therapies block the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), a serine/threonine protein kinase that regulates cell growth, division, and survival.

Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs)

Based on research showing that most clear cell renal cell carcinomas carried a variant resulting in constitutive production of cytokines stimulating angiogenesis, several agents that targeted VEGF-mediated pathways were developed. Several of these agents have been shown in randomized, controlled trials to significantly delay progression of clear cell renal cell carcinoma, but none has resulted in a statistically significant increase in OS as conventionally assessed. Many of these trials allowed crossover upon progression and, in some instances, other agents with similar biological activity were available to patients after they withdrew from the clinical trial. These circumstances may have made it more difficult to detect an OS benefit. For the clinician, this makes it challenging to determine the real benefit of these drugs to the patient. The four FDA-approved anti-VEGF agents include three oral TKIs: pazopanib, sorafenib, and sunitinib; and an anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody, bevacizumab. Axitinib is a newer, highly selective, and more potent inhibitor of VEGF receptors 1, 2, and 3. The FDA approved axitinib for the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma after the failure of one previously received systemic therapy.[55]

Cabozantinib

Cabozantinib is an oral TKI of the MET, AXL, and VEGF receptors. After a phase I trial showed activity against renal cell carcinoma, a phase III trial assessed the activity of cabozantinib in the second-line setting in a randomized controlled trial.

Evidence (cabozantinib):

- The METEOR trial (NCT01865747) randomly assigned 658 patients who had previously been treated with a VEGF TKI to receive either cabozantinib (60 mg qd) or everolimus (10 mg qd).[24,56] Doses were reduced in 60% of the patients receiving cabozantinib, compared with 25% of the patients assigned to everolimus.

- The incidence of grade 3 or 4 adverse events was 68% with cabozantinib compared with 58% with everolimus.

- The most common high-grade adverse events were hypertension (15%), diarrhea (11%), and fatigue (9%) with cabozantinib, compared with anemia (16%), fatigue (7%), and hyperglycemia (5%) with everolimus.

- Dose reductions of cabozantinib were mainly the result of diarrhea, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome, and fatigue.

- With a median follow-up of about 19 months, median OS was 21.4 months for patients who received cabozantinib and 16.5 months for patients who received everolimus (HR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.53–0.83; P = .0003).

- These results were confirmed when the prespecified final analysis was performed after 430 deaths had been confirmed. Median survival was 21.4 months with cabozantinib and 17.1 months with everolimus (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.58–0.85).[57]

- A subsequent trial compared cabozantinib with sunitinib in the first-line setting. The study randomly assigned 157 patients with intermediate- or poor-risk metastatic renal cell carcinoma to receive either cabozantinib or sunitinib.[9,10]

- Adverse events were seen in more than 95% of the patients.

- Grade 3 to 4 adverse events were seen in 68% of the patients on the cabozantinib arm and 65% of the patients on the sunitinib arm.

- Adverse events included hypertension, diarrhea, fatigue, and thrombocytopenia.

- Grade 5 adverse events occurred in 4% of the patients on the cabozantinib arm and 10% of the patients on the sunitinib arm.

- With a median follow-up of 34.5 months, there was no significant difference in OS between the two arms, and the OS curves crossed multiple times.

- PFS, however, was longer with cabozantinib (8.6 months vs. 5.3 months [HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.31–0.74]), demonstrating that PFS is an inadequate surrogate for OS.[9,10][Level of evidence B1]

- Adverse events were seen in more than 95% of the patients.

Sunitinib

Sunitinib and the combination of bevacizumab plus interferon alfa have each been associated with longer PFS than interferon alfa alone in randomized, controlled trials. Sunitinib is an orally available multikinase inhibitor (VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, PDGFR, c-Kit).

Evidence (sunitinib):

- In 750 previously untreated patients, all of whom had clear cell kidney cancer, a phase III trial compared sunitinib with interferon alfa.[12]

- Sunitinib as first-line systemic therapy was associated with a median PFS of 11 months, compared with 5 months for interferon alfa.

- The HR for progression was 0.42 (95% CI, 0.32–0.54; P < .001).[12][Level of evidence B1]

- However, the analysis for OS showed a strong but statistically nonsignificant trend to improved survival (26.4 months vs. 21.8 months; HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.669–1.001; P = .051).[13][Level of evidence B1]

Bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds to and neutralizes circulating VEGF protein, delayed progression of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma when compared with placebo in patients with disease refractory to biological therapy.[32] Similarly, bevacizumab plus interferon alfa as first-line therapy resulted in longer PFS but not OS compared with interferon alfa alone in two similarly designed, randomized, controlled trials.[33,34]

Pazopanib

Pazopanib is an orally available multikinase inhibitor (VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, VEGFR-3, PDGFR, and c-KIT) and has also been approved for the treatment of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma.

Evidence (pazopanib):

- Pazopanib was evaluated in a randomized, placebo-controlled, international trial (VEG015192 [NCT00334282]) that enrolled 435 patients with clear cell or predominantly clear cell renal cell carcinoma.[28] Nearly 50% of the patients had previously received cytokine therapy, although the remainder of them were treatment naïve.

- PFS was significantly prolonged in the pazopanib arm at 9.2 months compared with 4.2 months in the placebo arm.

- The HR for progression was 0.46 (95% CI, 0.34–0.62; P < .0001), and the median duration of response was longer than 1 year.

- Pazopanib was also compared with sunitinib in a randomized controlled trial (NCT00720941) that enrolled 1,110 patients who had metastatic renal cell carcinoma with a clear cell component in a 1:1 ratio.[14] The primary end point was PFS. The study was powered to assess the noninferiority of pazopanib. Results were reported when there was disease progression in 336 of 557 patients (60%) who received pazopanib and in 323 of 553 patients (58%) who received sunitinib.

- The median PFS was 8.4 months for those in the pazopanib arm and 9.5 months for those in the sunitinib arm (HR, 1.05; CI, 0.9–1.22).

- There was no difference in OS (HR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.76–1.08).

- Although QOL was compared in the study, differences in the scheduled administration of the medications made this comparison difficult to interpret.

- A subsequent double-blind, randomized, controlled, crossover trial compared sunitinib followed by pazopanib with pazopanib followed by sunitinib. The primary end point was patient preference for one drug over the other.[15] Patients were treated for 10 weeks with either sunitinib or pazopanib, followed by a 2-week washout period, followed by 10 more weeks of treatment with the other drug. Preference was assessed at the end of the second 10-week treatment period. This study design created possible bias in favor of pazopanib.

Although the typical regimen for administering sunitinib is a 6-week cycle of 4 weeks on the drug and 2 weeks off the drug, the Patient Preference Study of Pazopanib Versus Sunitinib in Advanced or Metastatic Kidney Cancer (PISCES [NCT01064310]) chose a treatment period of 10 weeks rather than 12 weeks. Because of this treatment-period change, the 10 weeks of sunitinib treatment included 4 weeks on the drug, followed by 2 weeks off the drug, followed by 4 more weeks on the drug. Patients assigned to pazopanib followed by sunitinib had their preference for treatment assessed at the end of the second 4-weeks-on-the-drug period during which they took sunitinib daily for 28 days. At that point, the sunitinib side effects became the most severe. The expected result from an assessment conducted at the end of a 6-week treatment cycle versus the 4-week treatment cycle would be greatly abated side effects.

In addition, the 2-week washout period that occurred between the two 10-week treatment periods was a true break from treatment for patients assigned to take pazopanib first; however, for the patients taking sunitinib, the 2-week washout period was just the completion of their second 6-week treatment cycle. In other words, patients assigned to pazopanib first had a true 2-week break from treatment, and their drug preference was assessed at the peak period of toxic effects from sunitinib; however, the patients assigned to sunitinib first had no true treatment break before starting pazopanib and may have had less opportunity to recover from the side effects of sunitinib.

- Despite these limitations, 70% of the patients preferred pazopanib, and 22% of the patients preferred sunitinib (P < .001).

- More patients preferred pazopanib regardless of the treatment they received first; however, that difference was greater for the patients who received pazopanib first (80% vs. 11%) compared with the patients who received sunitinib first (62% vs. 32%).

- The main side effects cited by the patients that contributed to patient preference were diarrhea, HRQOL, fatigue, loss of appetite, taste changes, nausea and vomiting, hand and foot soreness, stomach pain, and mouth and throat soreness.

- The patients who preferred pazopanib cited less fatigue and better overall QOL as the most common reasons for their preference.

- The patients who preferred sunitinib cited less diarrhea and better QOL as the most common reasons for their preference.

- Physician preference was a secondary end point of the study, and 61% of physicians preferred to continue patient treatment with pazopanib, compared with 22% of physicians who preferred to continue patient treatment with sunitinib.

Sorafenib

Sorafenib is an orally available multikinase inhibitor (CRAF, BRAF, KIT, FLT-3, VEGFR-2, VEGFR-3, and PDGFRB) and has also been approved for the treatment of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma.[58]

Evidence (sorafenib):

- In an international, multicenter, randomized trial, 769 patients were stratified by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center prognostic risk category and by country. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either sorafenib (400 mg bid) or a placebo. Approximately 82% of the patients had received IL-2 previously and/or interferon alfa in both arms of the study. The primary end points were PFS and OS.

- The median PFS for patients randomly assigned to sorafenib was 167 days compared with 84 days for patients randomly assigned to placebo (P < .001).

- The estimated HR for the risk of progression with sorafenib compared with a placebo was 0.44 (95% CI, 0.35–0.55). There was no significant difference in OS.[58][Level of evidence B1]

- A phase II study randomly assigned 189 patients to either sorafenib or interferon alfa.[29]

- No difference was reported in PFS (5.7 months vs. 5.6 months), but sorafenib was associated with better QOL than interferon alfa.

Axitinib

Axitinib has prolonged PFS when given as second-line systemic therapy.

Evidence (axitinib):

- A randomized controlled trial of 723 patients conducted at 175 sites in 22 countries evaluated axitinib versus sorafenib as treatment for renal cell carcinoma. Patients had disease with a clear cell component that had progressed during or after first-line treatment with sunitinib (54%), cytokines (35%), bevacizumab plus interferon alfa (8%), or temsirolimus (3%).[36,55] The primary end point was PFS, and the data were analyzed when disease in 88% of the axitinib patients and 90% of the sorafenib patients had progressed, while 58% and 59%, respectively, had died.

- Median PFS was 8.3 months for axitinib and 5.7 months for sorafenib (HRprogression or death, 0.656; 95% CI, 0.552–0.779, one-sided log-rank P < .0001 and a threshold of P < .025 for significance).

- Median OS was 20.1 months with axitinib compared with 19.2 months with sorafenib (HR, 0.969; 95% CI, 0.80–1.17, P = .374).

- However, the largest benefit was seen in patients who received cytokines as first-line therapy and whose median PFS was 12.2 months with axitinib compared with 8.2 months with sorafenib (P < .0001), while median OS was 29.4 months with axitinib compared with 27.8 months with sorafenib (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.55–1.19; P = .144).

- In contrast, in patients who had previously received sunitinib, axitinib was associated with a 2.1-month increase in PFS compared with sorafenib (6.5 months vs. 4.4 months, one-sided P = .002), but median OS was nearly identical: 15.2 months with axitinib compared with 16.5 months with sorafenib (HR, 1.0; 95% CI, 0.782–1.270; P = .49).[36]

Comparing the toxicity of the axitinib and sorafenib regimens is complicated because the axitinib arm included a dose-escalation component, and only those patients who tolerated the lower dose were subsequently given the higher doses. Hypertension, nausea, dysphonia, and hypothyroidism were more common with axitinib, whereas palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, alopecia, and rash were more common with sorafenib.[36,55]

Tivozanib

Tivozanib is a TKI that is selective for the VEGF receptor. A phase III randomized controlled trial compared tivozanib with sorafenib for first-line treatment of patients with metastatic renal cell cancer. The study reported that tivozanib was associated with a longer median PFS, but OS favored sorafenib.[26] A subsequent phase III randomized controlled trial compared the two drugs in patients who had at least two prior systemic treatments, including at least one prior VEGF inhibitor. This second trial reported a longer median PFS for patients treated with tivozanib and no difference in OS.[27] In the United States, the FDA has approved tivozanib for patients who have had two or more prior systemic therapies.

Evidence (tivozanib):

- In an open-label, phase III, randomized controlled trial, tivozanib was compared with sorafenib as initial targeted therapy. The study included 517 patients with metastatic renal cell cancer with a clear cell component who had received zero to one prior systemic therapy. Prior treatment with VEGF-targeted therapy and mTOR inhibitors was not permitted. The primary end point was PFS.[26]

- The median PFS was longer for patients who received tivozanib than for patients who received sorafenib (11.9 months vs. 9.1 months; HR, 0.797; 95% CI, 0.639–0.993; P = .042). A total of 156 patients (61%) who had disease progression while receiving sorafenib crossed over to receive tivozanib.[26][Level of evidence B1]

- There was no difference in OS.

- The two medications had different toxicity profiles. Adverse events that were more common with tivozanib than with sorafenib included hypertension (44% vs. 34%) and dysphonia (21% vs. 5%). Adverse events that were more common with sorafenib than with tivozanib included hand-foot skin reaction (54% vs. 14%) and diarrhea (33% vs. 23%).

- In an open-label randomized controlled trial (NCT02627963), tivozanib was compared with sorafenib. The study included 350 patients with metastatic renal cell cancer who had previously been treated with at least two different systemic therapies, including one VEGF inhibitor.[27]

- With a median follow-up of 19.0 months, the median PFS was longer for patients who received tivozanib (5.6 months vs. 3.9 months; HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.56–0.94; P = .016).[27][Level of evidence B1]

- No significant difference was reported for OS. The median OS was 16.4 months for patients who received tivozanib and 19.2 months for patients who received sorafenib (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.75–1.24).[59]

- Grades 3 to 4 treatment-related adverse events were reported in 11% of patients who received tivozanib and 10% of patients who received sorafenib.

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors

Temsirolimus

Temsirolimus is an intravenously administered mTOR inhibitor.

Evidence (temsirolimus):

- A phase III randomized controlled trial enrolled intermediate- and poor-risk patients with a variety of subtypes of renal cell carcinoma. The trial was not restricted to clear cell kidney cancer.

- Temsirolimus was shown to result in prolonged OS compared with interferon alfa.

- The HRdeath was 0.73 (95% CI, 0.58–0.92; P = .008), making temsirolimus the only therapy for renal cell carcinoma to clearly show results in longer OS than did interferon alfa using conventional statistical analysis.[31]

Everolimus

Everolimus is an orally administered mTOR inhibitor.

Evidence (everolimus):

- Everolimus was evaluated in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trial that enrolled patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma with a clear cell component that had progressed during or within 6 months of stopping treatment with sunitinib, sorafenib, or both drugs.

- Median PFS was 4.0 months with everolimus compared with 1.9 months with placebo.[37]

- No difference in OS was reported.

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-2alpha inhibitors

Belzutifan

Belzutifan is an HIF-2alpha inhibitor used to treat advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma in patients with disease progression after one to three prior lines of systemic therapy, including immune checkpoint inhibitors and VEGF-targeted treatments.

- The open-label phase III LITESPARK-005 trial (NCT04195750) compared belzutifan with everolimus in patients with advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma who experienced disease progression after one to three lines of prior systemic therapies, including immune checkpoint inhibitors and VEGF-targeted treatments. The co-primary end points of the study were PFS, as assessed by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1 via blinded independent central review, and OS.[25]

- The trial demonstrated a significant improvement in PFS with belzutifan compared with everolimus (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.63–0.90; P = .0016). Objective response rates were also 19.2% higher in the belzutifan arm (95% CI, 14.8%–24.0%). However, OS did not improve significantly (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.73–1.07; P = .20), indicating no clinically meaningful survival difference. The lack of OS benefit raises concerns about the clinical meaningfulness of the PFS improvement.[25][Level of evidence B1]

- Grade 3 or higher adverse events of any cause occurred in 61.8% of patients in the belzutifan group (grade 5 severity occurred in 3.5% of patients) and in 62.5% of patients in the everolimus group (grade 5 severity occurred in 5.3% of patients). Adverse events led to treatment discontinuation in 5.9% of patients in the belzutifan group and 14.7% of patients in the everolimus group.

The FDA approved belzutifan for the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma in the second-line and beyond based on the PFS benefit observed in the trial. However, the trial did not meet the co-primary end point of OS. Also, the cost of belzutifan is $31,000 per month for uninsured patients, while everolimus, a generic drug, costs approximately $450 per month (in 2024 dollars).

Combined Therapy With Multitargeted TKIs and mTOR Inhibitors

Lenvatinib plus everolimus

Lenvatinib is a multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor with activity against VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, and VEGFR-3, with inhibitory activity against fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, and FGFR4), PDGFRA, RET, and KIT.

Evidence (lenvatinib plus everolimus):

- The combination of lenvatinib plus everolimus was compared with each medication as a single agent in a randomized, controlled phase II study of 153 subjects with advanced-stage renal cell carcinoma who had received previous antiangiogenic therapy.[23] The primary end point was PFS.

- Median PFS was significantly longer in the combination arm (14.6 months) than in the everolimus arm (5.5 months) (HR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.24–0.68).[23][Level of evidence B1]

- Median PFS was 7.4 months for lenvatinib, which was not significantly shorter than in the combination arm (HR, 0.66; 0.39–1.10), but was significantly longer than in the everolimus arm (HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.38–0.98; P = .048).

- There was no significant difference in OS at the time of data cutoff. A later, post hoc analysis of OS with longer follow-up did show longer survival in the combination arm compared with the everolimus-alone arm (25.5 months [95% CI, 16.4 to not evaluable] vs. 15.4 months [95% CI, 11.8–19.6]; HR, 0.51; 95% CI, 0.30–0.88; P = .024).

- Median OS in the lenvatinib-alone arm was 19.1 months and did not differ significantly from the other two arms.

- All patients experienced adverse events and almost all of these were judged to be related to treatment. Seventy-one percent of patients had adverse events that were grade 3 or higher. The most common toxicities in the combination arm were diarrhea, hypertension, fatigue, loss of appetite, vomiting, and cough. One patient in the combination arm died of a cerebral hemorrhage that was thought to be related to treatment.

Chemotherapy

Responses to cytotoxic chemotherapy generally have not exceeded 10% for any regimen that has been studied in adequate numbers of patients.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, et al.: Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab versus Sunitinib in Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 378 (14): 1277-1290, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rini BI, Plimack ER, Stus V, et al.: Pembrolizumab plus Axitinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 380 (12): 1116-1127, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Motzer R, Alekseev B, Rha SY, et al.: Lenvatinib plus Pembrolizumab or Everolimus for Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 384 (14): 1289-1300, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Choueiri TK, Powles T, Burotto M, et al.: Nivolumab plus Cabozantinib versus Sunitinib for Advanced Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 384 (9): 829-841, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Flanigan RC, Salmon SE, Blumenstein BA, et al.: Nephrectomy followed by interferon alfa-2b compared with interferon alfa-2b alone for metastatic renal-cell cancer. N Engl J Med 345 (23): 1655-9, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mickisch GH, Garin A, van Poppel H, et al.: Radical nephrectomy plus interferon-alfa-based immunotherapy compared with interferon alfa alone in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma: a randomised trial. Lancet 358 (9286): 966-70, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Méjean A, Ravaud A, Thezenas S, et al.: Sunitinib Alone or after Nephrectomy in Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 379 (5): 417-427, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mathieu R, Pignot G, Ingles A, et al.: Nephrectomy improves overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma in cases of favorable MSKCC or ECOG prognostic features. Urol Oncol 33 (8): 339.e9-15, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Choueiri TK, Halabi S, Sanford BL, et al.: Cabozantinib Versus Sunitinib As Initial Targeted Therapy for Patients With Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma of Poor or Intermediate Risk: The Alliance A031203 CABOSUN Trial. J Clin Oncol 35 (6): 591-597, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]