Merkel Cell Carcinoma Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version

General Information About Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) was originally described by Toker in 1972 as trabecular carcinoma of the skin.[1] Other names for MCC include Toker tumor, primary small cell carcinoma of the skin, primary cutaneous neuroendocrine tumor, and malignant trichodiscoma.[2]

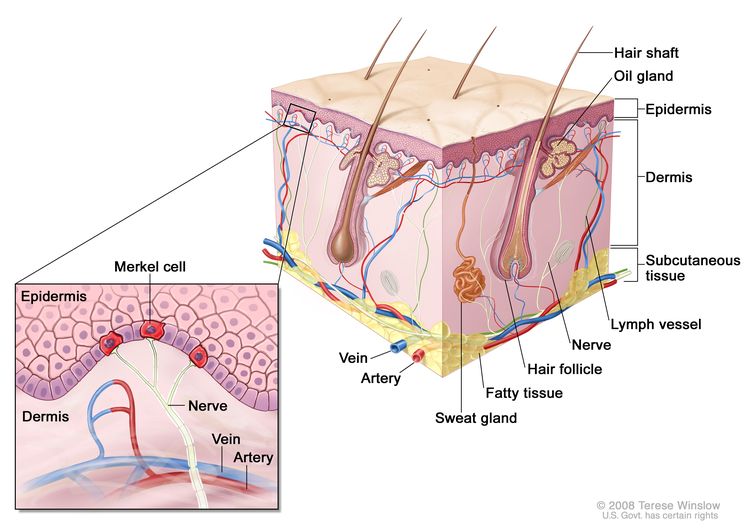

MCC is an aggressive neuroendocrine carcinoma arising in the dermoepidermal junction (see Figure 1), and it is the second most common cause of skin cancer death after melanoma.[3,4] Although the exact origin and function of the Merkel cell remains under investigation, it is thought to have features of both epithelial and neuroendocrine origin and arise in cells with touch-sensitivity function (mechanoreceptors).[5-11]

Therapeutic options have been historically limited for patients with advanced disease. However, new immunotherapeutic approaches are associated with durable responses.[12]

Anatomy

Incidence and Mortality

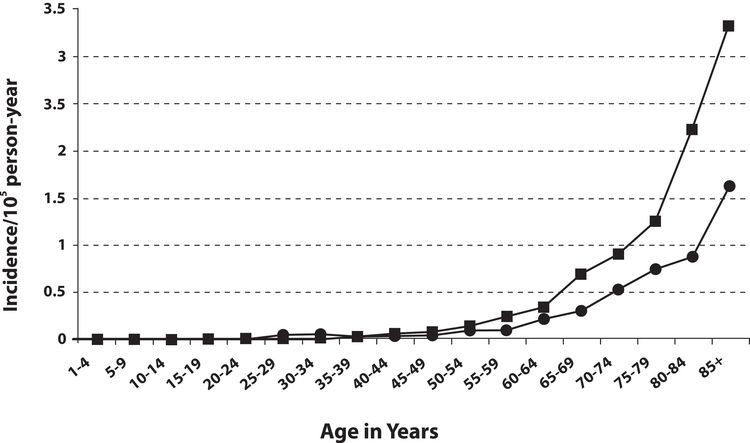

MCC incidence increases progressively with age. There are few cases in patients younger than 50 years, and the median age at diagnosis is about 65 years (see Figure 2).[13] Incidence is considerably greater in White individuals than in Black individuals and slightly greater in men than in women.[13-17]

MCC occurs most frequently in sun-exposed areas of skin, particularly the head and neck, followed by the extremities, and then the trunk.[5,16,18] Incidence has been reported to be greater in geographic regions with higher levels of ultraviolet B sunlight.[16]

As of 2013, MCC had an annual incidence of 0.7 cases per 100,000 people in the United States.[19] The incidence has been increasing over the past several decades, almost doubling in the United States between 2000 and 2013. This rise is potentially related to more accurate diagnostic pathology tools, improved clinical awareness of MCC, an aging population, increased sun exposure in susceptible populations, and improved registry tools. The incidence is also higher in immunosuppressed populations (HIV, hematologic malignancies, immunosuppressive medications, etc.).[20] Approximately 25,000 cases of MCC have been recorded in the United States since 2000, including more than 2,200 incident cases reported in 2014 to the National Program of Cancer Registries/SEER combined registries, which captures more than 98% of the U.S. population and the ten most common sites of MCC (see Table 1).[17]

| Anatomical Site | Cases (%) |

|---|---|

| NOS = not otherwise specified; SEER = Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. | |

| aAlbores-Saavedra J et al: Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3,870 cases: A population-based study. J Cutan Pathol. Reprinted with permission © 2009. Published by Wiley-Blackwell. All rights reserved.[17] | |

| Skin, face | 1,041 (26.9) |

| Skin of upper limb and shoulder | 853 (22.0) |

| Skin of lower limb and hip | 578 (14.9) |

| Skin of trunk | 410 (10.6) |

| Skin of scalp and neck | 348 (9.0) |

| Skin, NOS | 234 (6.0) |

| External ear | 120 (3.1) |

| Eyelid | 98 (2.5) |

| Skin of lip | 91 (2.4) |

| Unknown primary site | 31 (0.8) |

| Total | 3,804 (98.3) |

In various cases series, up to 97% of MCCs arise in the skin. MCC primaries in other sites were very rare, as were MCCs from unknown primary sites.[17]

SEER registry data have shown excess risk of MCC as a first or second cancer in patients with several primary cancers.[21] National cancer registries from three Scandinavian countries have identified a variety of second cancers diagnosed after MCC.[22]

Pathogenesis

Increased incidence of MCC has also been seen in people treated heavily with methoxsalen (psoralen) and ultraviolet A (PUVA) for psoriasis (3 of 1,380 patients, 0.2%). This has also been seen in individuals with chronic immune suppression, especially from chronic lymphocytic leukemia, HIV, and previous solid organ transplant.[16,23]

In 2008, a novel polyomavirus (Merkel cell polyoma virus [MCPyV]) was first reported in MCC tumor specimens,[24] a finding subsequently confirmed in other laboratories.[25-27] High levels of viral DNA and clonal integration of the virus in MCC tumors have also been reported, [28] along with expression of certain viral antigens in MCC cells and the presence of antiviral antibodies. Not all cases of MCC appear to be associated with MCPyV infection.[29]

MCPyV has been detected at very low levels in normal skin distant from the MCC primary tumor, in a significant percentage of patients with non-MCC cutaneous disorders, in normal-appearing skin in healthy individuals, and in nonmelanoma skin cancers in immune-suppressed individuals.[10,30-32] Various methods have been used to identify and quantify the presence of MCPyV in MCC tumor specimens, other non-MCC tumors, blood, urine, and other tissues.[33,34]

The significance of the new MCPyV findings remains uncertain. The prognostic significance of viral load, antibody titer levels, and the role of underlying immunosuppression in hosts (from disease and medications) are under investigation.

Prevalence of MCPyV appears to differ between MCC patients in the United States and Europe versus Australia. There may be two independent pathways for the development of MCC: one driven by the presence of MCPyV, and the other driven primarily by sun damage, especially as noted in patient series from Australia.[25,29,35]

Although no unique marker for MCC has been identified, a variety of molecular and cytogenetic markers of MCC have been reported.[7,10,36]

Clinical Presentation

MCC usually presents as a painless, indurated, solitary dermal nodule with a slightly erythematous to deeply violaceous color, and rarely, an ulcer. MCC can infiltrate locally via dermal lymphatics, resulting in multiple satellite lesions. Because of its nonspecific clinical appearance, MCC is rarely suspected before a biopsy is performed.[5] Photographs of MCC skin lesions illustrate its clinical variability.[37]

A mnemonic [18] summarizing typical clinical characteristics of MCC has been proposed:

AEIOU

- A = Asymptomatic.

- E = Expanding rapidly.

- I = Immune suppressed.

- O = Older than 50 years.

- U = UV-exposed skin.

Not all patients have every element in this mnemonic. However, in this study, 89% of patients met three or more criteria, 52% met four or more criteria, and 7% met all five criteria.[18]

Initial Clinical Evaluation

Because local-regional spread is common, patients with newly diagnosed MCC require a careful clinical examination for satellite lesions and regional nodal involvement.

Tailoring an imaging work-up to the clinical presentation and any relevant signs and symptoms should be considered. There has been no systematic study of the optimal imaging work-up for newly diagnosed patients, and it is not clear if all newly diagnosed patients, especially those with the smallest primary tumors, benefit from a detailed imaging work-up.

If an imaging work-up is performed, it may include a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen to rule out primary small cell lung cancer as well as distant and regional metastases. Imaging studies designed to evaluate suspicious signs and symptoms may also be recommended. In one series, CT scans had an 80% false-negative rate for regional metastases.[38] Head and neck presentations may require additional imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging has been used to evaluate MCC but has not been studied systematically.[39] Fluorine F 18-fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography results have been reported in selected cases.[40,41] Baseline routine blood work has been recommended but has not been studied systematically. There are no known circulating tumor markers specific to MCC.

Initial Staging Results

The results of initial clinical staging of MCC vary widely in the literature, based on retrospective case series reported over decades. For invasive cancers, 48.6% were localized, 31.1% were regional, and 8.2% were distant.[17]

MCC that presents in regional nodes without an identifiable primary lesion is found in a minority of patients, with the percent of these cases varying among the reported series. Tumors without an identifiable primary lesion have been attributed to either spontaneous regression of the primary or metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma from a clinically occult site.[8,17,18,42,43]

Clinical Progression

In a review of patients from 18 case series, 279 of 926 patients (30.1%) developed local recurrence during follow-up, excluding those presenting with distant metastatic disease. These events have been typically attributed to inadequate surgical margins and/or a lack of adjuvant radiation therapy. In addition, 545 of 982 patients (55.5%) had lymph node metastases at diagnosis or during follow-up.[8]

In the same review of 18 case series, the most common sites of distant metastases were distant lymph nodes (60.1%), distant skin (30.3%), lung (23.4%), central nervous system (18.4%), and bone (15.2%).[8] Many other sites of disease have also been reported, and the distribution of metastatic sites varies among case series.

In one series of 237 patients presenting with local or regional disease, the median time-to-recurrence was 9 months (range, 2–70 months). Ninety-one percent of recurrences occurred within 2 years of diagnosis.[44]

Potential Prognostic Factors

The extent of disease at presentation may provide the most useful estimate of prognosis.[7]

Diagnostic procedures, such as sentinel lymph node biopsy, may help distinguish between local and regional disease at presentation. One-third of patients who lack clinically palpable or radiologically visible nodes will have microscopically evident regional disease.[38] Nodal positivity may be substantially lower among patients with small tumors (e.g., ≤1.0 cm).[45]

Many retrospective studies have evaluated the relationship of a wide variety of biological and histological factors to survival and local-regional control.[7,8,17,38,44,46-57][Level of evidence C2] Many of these reports are confounded by small numbers, potential selection bias, referral bias, short follow-up, no uniform clinical protocol for both staging and treatment, and are underpowered to detect modest differences.

A large, single-institution, retrospective study of 156 patients with MCC, with a median follow-up of 51 months (range, 2–224 months), evaluated histological factors potentially associated with prognosis.[55][Level of evidence C1] Although this report was subject to potential selection and referral bias, both univariate and multivariate analyses demonstrated a relationship between improved cause-specific survival and circumscribed growth pattern versus infiltrative pattern, shallow-tumor depth versus deep-tumor depth, and absence of lymphovascular invasion versus presence of lymphovascular invasion. Adoption of these findings into a global prognostic algorithm awaits independent confirmation by adequately powered studies.

A 2009 study investigated whether the presence of newly identified MCPyV in MCC tumor specimens influenced clinical outcome among 114 Finnish patients with MCC. In this small study, patients whose tumors were MCPyV positive appeared to have better survival than patients whose tumors were MCPyV negative.[58][Level of evidence C2] Standardization of procedures to identify and quantify MCPyV and relevant antibodies is needed to improve understanding of both prognostic and epidemiological questions.[10]

Prognosis

The most significant prognostic parameters for MCC include tumor size and the presence of locoregional or distant metastases. These factors form the basis of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for MCC.[59,60] Although an increasing primary tumor size correlates with an increased risk of metastatic disease, MCC tumors of any size have significant risk of occult metastasis, supporting the use of sentinel lymph node biopsy for all cases.[61] Additional features of the primary tumor, such as lymphovascular invasion and tumor growth pattern, may also have prognostic significance. Clinically detectable nodal disease is associated with worse outcome than microscopic metastases.[55,59] Other findings associated with worse prognosis include sheet-like involvement in lymph node metastases and an increasing number of metastatic lymph nodes.[60,62]

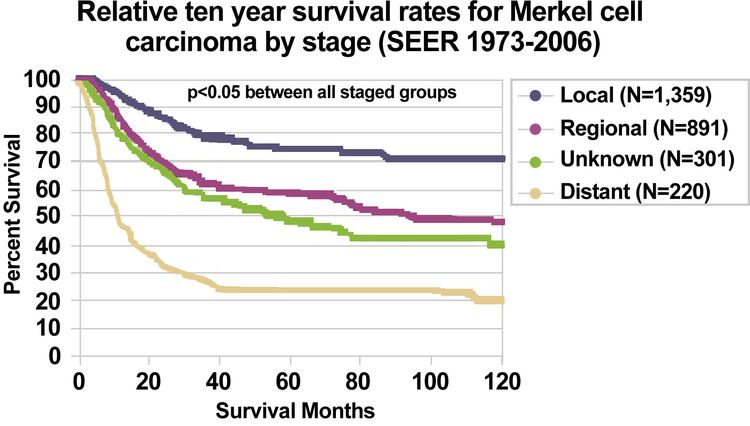

The bulk of MCC literature is from small case series, which are subject to many confounding factors. For this reason, the relapse and survival rates reported by stage vary widely in the literature. In general, lower-stage disease is associated with better overall survival.[63] For more information, see the Potential Prognostic Factors section.

Outcomes from patients presenting with small volume local disease and pathologically confirmed cancer-negative lymph nodes report a cause-specific 5-year survival rate exceeding 90% in one report.[44,55][Level of evidence C2]

A tabular summary of treatment results of MCC from 12 series illustrates the difficulty in comparing outcome data among series.[7]

Using the SEER Program registry MCC staging system adopted in 1973, MCC survival data (1973–2006) by stage is summarized in Figure 3.[17]

References

- Toker C: Trabecular carcinoma of the skin. Arch Dermatol 105 (1): 107-10, 1972. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schwartz RA, Lambert WC: The Merkel cell carcinoma: a 50-year retrospect. J Surg Oncol 89 (1): 5, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Agelli M, Clegg LX, Becker JC, et al.: The etiology and epidemiology of merkel cell carcinoma. Curr Probl Cancer 34 (1): 14-37, 2010 Jan-Feb. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Harms PW: Update on Merkel Cell Carcinoma. Clin Lab Med 37 (3): 485-501, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Nghiem P, McKee PH, Haynes HA: Merkel cell (cutaneous neuroendocrine) carcinoma. In: Sober AJ, Haluska FG, eds.: Skin Cancer. BC Decker Inc., 2001, pp 127-141.

- Nghiem P, James N: Merkel cell carcinoma. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al., eds.: Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill , 2008, pp 1087-94.

- Eng TY, Boersma MG, Fuller CD, et al.: A comprehensive review of the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol 30 (6): 624-36, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Medina-Franco H, Urist MM, Fiveash J, et al.: Multimodality treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: case series and literature review of 1024 cases. Ann Surg Oncol 8 (3): 204-8, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Busse PM, Clark JR, Muse VV, et al.: Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 19-2008. A 63-year-old HIV-positive man with cutaneous Merkel-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 358 (25): 2717-23, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rockville Merkel Cell Carcinoma Group: Merkel cell carcinoma: recent progress and current priorities on etiology, pathogenesis, and clinical management. J Clin Oncol 27 (24): 4021-6, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Calder KB, Smoller BR: New insights into merkel cell carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol 17 (3): 155-61, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cassler NM, Merrill D, Bichakjian CK, et al.: Merkel Cell Carcinoma Therapeutic Update. Curr Treat Options Oncol 17 (7): 36, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Agelli M, Clegg LX: Epidemiology of primary Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol 49 (5): 832-41, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hodgson NC: Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends. J Surg Oncol 89 (1): 1-4, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Young JL, Ward KC, Ries LAG: Cancer of rare sites. In: Ries LAG, Young JL, Keel GE, et al., eds.: SEER Survival Monograph: Cancer Survival Among Adults: U. S. SEER Program, 1988-2001, Patient and Tumor Characteristics. National Cancer Institute, 2007. NIH Pub. No. 07-6215, pp 251-61.

- Miller RW, Rabkin CS: Merkel cell carcinoma and melanoma: etiological similarities and differences. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 8 (2): 153-8, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population based study. J Cutan Pathol 37 (1): 20-7, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, et al.: Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. J Am Acad Dermatol 58 (3): 375-81, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Paulson KG, Park SY, Vandeven NA, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma: Current US incidence and projected increases based on changing demographics. J Am Acad Dermatol 78 (3): 457-463.e2, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ma JE, Brewer JD: Merkel cell carcinoma in immunosuppressed patients. Cancers (Basel) 6 (3): 1328-50, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Howard RA, Dores GM, Curtis RE, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma and multiple primary cancers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15 (8): 1545-9, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bzhalava D, Bray F, Storm H, et al.: Risk of second cancers after the diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma in Scandinavia. Br J Cancer 104 (1): 178-80, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lunder EJ, Stern RS: Merkel-cell carcinomas in patients treated with methoxsalen and ultraviolet A radiation. N Engl J Med 339 (17): 1247-8, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, et al.: Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science 319 (5866): 1096-100, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Garneski KM, Warcola AH, Feng Q, et al.: Merkel cell polyomavirus is more frequently present in North American than Australian Merkel cell carcinoma tumors. J Invest Dermatol 129 (1): 246-8, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Becker JC, Houben R, Ugurel S, et al.: MC polyomavirus is frequently present in Merkel cell carcinoma of European patients. J Invest Dermatol 129 (1): 248-50, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kassem A, Schöpflin A, Diaz C, et al.: Frequent detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinomas and identification of a unique deletion in the VP1 gene. Cancer Res 68 (13): 5009-13, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Houben R, Schrama D, Becker JC: Molecular pathogenesis of Merkel cell carcinoma. Exp Dermatol 18 (3): 193-8, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Paik JY, Hall G, Clarkson A, et al.: Immunohistochemistry for Merkel cell polyomavirus is highly specific but not sensitive for the diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma in the Australian population. Hum Pathol 42 (10): 1385-90, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Andres C, Belloni B, Puchta U, et al.: Prevalence of MCPyV in Merkel cell carcinoma and non-MCC tumors. J Cutan Pathol 37 (1): 28-34, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kassem A, Technau K, Kurz AK, et al.: Merkel cell polyomavirus sequences are frequently detected in nonmelanoma skin cancer of immunosuppressed patients. Int J Cancer 125 (2): 356-61, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Foulongne V, Dereure O, Kluger N, et al.: Merkel cell polyomavirus DNA detection in lesional and nonlesional skin from patients with Merkel cell carcinoma or other skin diseases. Br J Dermatol 162 (1): 59-63, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- DeCaprio JA: Does detection of Merkel cell polyomavirus in Merkel cell carcinoma provide prognostic information? J Natl Cancer Inst 101 (13): 905-7, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Laude HC, Jonchère B, Maubec E, et al.: Distinct merkel cell polyomavirus molecular features in tumour and non tumour specimens from patients with merkel cell carcinoma. PLoS Pathog 6 (8): , 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Buck CB, Lowy DR: Immune readouts may have prognostic value for the course of merkel cell carcinoma, a virally associated disease. J Clin Oncol 29 (12): 1506-8, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lemos B, Nghiem P: Merkel cell carcinoma: more deaths but still no pathway to blame. J Invest Dermatol 127 (9): 2100-3, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Seattle Cancer Care Alliance: Merkel Cell Carcinoma Information for Patients and Their Physicians: Clinical Photos/Images. Seattle, Wa: Seattle Cancer Care Alliance Skin Oncology Clinic, 2009. Available online. Last accessed May 9, 2025.

- Gupta SG, Wang LC, Peñas PF, et al.: Sentinel lymph node biopsy for evaluation and treatment of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma: The Dana-Farber experience and meta-analysis of the literature. Arch Dermatol 142 (6): 685-90, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Anderson SE, Beer KT, Banic A, et al.: MRI of merkel cell carcinoma: histologic correlation and review of the literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol 185 (6): 1441-8, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Iagaru A, Quon A, McDougall IR, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma: Is there a role for 2-deoxy-2-[f-18]fluoro-D-glucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography? Mol Imaging Biol 8 (4): 212-7, 2006 Jul-Aug. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Belhocine T, Pierard GE, Frühling J, et al.: Clinical added-value of 18FDG PET in neuroendocrine-merkel cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep 16 (2): 347-52, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Missotten GS, de Wolff-Rouendaal D, de Keizer RJ: Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid review of the literature and report of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma showing spontaneous regression. Ophthalmology 115 (1): 195-201, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Richetta AG, Mancini M, Torroni A, et al.: Total spontaneous regression of advanced merkel cell carcinoma after biopsy: review and a new case. Dermatol Surg 34 (6): 815-22, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol 23 (10): 2300-9, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Stokes JB, Graw KS, Dengel LT, et al.: Patients with Merkel cell carcinoma tumors < or = 1.0 cm in diameter are unlikely to harbor regional lymph node metastasis. J Clin Oncol 27 (23): 3772-7, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jabbour J, Cumming R, Scolyer RA, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma: assessing the effect of wide local excision, lymph node dissection, and radiotherapy on recurrence and survival in early-stage disease--results from a review of 82 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1992 and 2004. Ann Surg Oncol 14 (6): 1943-52, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Henness S, Vereecken P: Management of Merkel tumours: an evidence-based review. Curr Opin Oncol 20 (3): 280-6, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Skelton HG, Smith KJ, Hitchcock CL, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma: analysis of clinical, histologic, and immunohistologic features of 132 cases with relation to survival. J Am Acad Dermatol 37 (5 Pt 1): 734-9, 1997. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sandel HD, Day T, Richardson MS, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma: does tumor size or depth of invasion correlate with recurrence, metastasis, or patient survival? Laryngoscope 116 (5): 791-5, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Llombart B, Monteagudo C, López-Guerrero JA, et al.: Clinicopathological and immunohistochemical analysis of 20 cases of Merkel cell carcinoma in search of prognostic markers. Histopathology 46 (6): 622-34, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Senchenkov A, Barnes SA, Moran SL: Predictors of survival and recurrence in the surgical treatment of merkel cell carcinoma of the extremities. J Surg Oncol 95 (3): 229-34, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Goldberg SR, Neifeld JP, Frable WJ: Prognostic value of tumor thickness in patients with Merkel cell carcinoma. J Surg Oncol 95 (8): 618-22, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Heath ML, Nghiem P: Merkel cell carcinoma: if no breslow, then what? J Surg Oncol 95 (8): 614-5, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tai P: Merkel cell cancer: update on biology and treatment. Curr Opin Oncol 20 (2): 196-200, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Andea AA, Coit DG, Amin B, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma: histologic features and prognosis. Cancer 113 (9): 2549-58, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Paulson KG, Iyer JG, Tegeder AR, et al.: Transcriptome-wide studies of merkel cell carcinoma and validation of intratumoral CD8+ lymphocyte invasion as an independent predictor of survival. J Clin Oncol 29 (12): 1539-46, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Fields RC, Busam KJ, Chou JF, et al.: Recurrence and survival in patients undergoing sentinel lymph node biopsy for merkel cell carcinoma: analysis of 153 patients from a single institution. Ann Surg Oncol 18 (9): 2529-37, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sihto H, Kukko H, Koljonen V, et al.: Clinical factors associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus infection in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 101 (13): 938-45, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Harms KL, Healy MA, Nghiem P, et al.: Analysis of Prognostic Factors from 9387 Merkel Cell Carcinoma Cases Forms the Basis for the New 8th Edition AJCC Staging System. Ann Surg Oncol 23 (11): 3564-3571, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Iyer JG, Storer BE, Paulson KG, et al.: Relationships among primary tumor size, number of involved nodes, and survival for 8044 cases of Merkel cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 70 (4): 637-643, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schwartz JL, Griffith KA, Lowe L, et al.: Features predicting sentinel lymph node positivity in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 29 (8): 1036-41, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ko JS, Prieto VG, Elson PJ, et al.: Histological pattern of Merkel cell carcinoma sentinel lymph node metastasis improves stratification of Stage III patients. Mod Pathol 29 (2): 122-30, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Eng TY, Boersma MG, Fuller CD, et al.: Treatment of merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol 27 (5): 510-5, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

Cellular Classification of Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Although the exact origin and function of the Merkel cell remains under investigation, it is thought to have features of both epithelial and neuroendocrine origin and arise in cells with touch-sensitivity function (mechanoreceptors).[1-4]

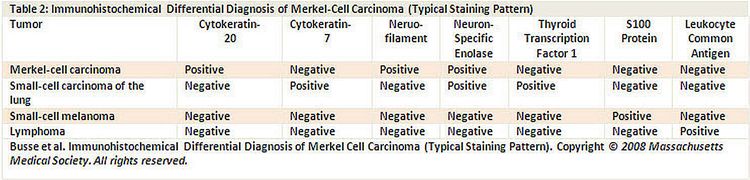

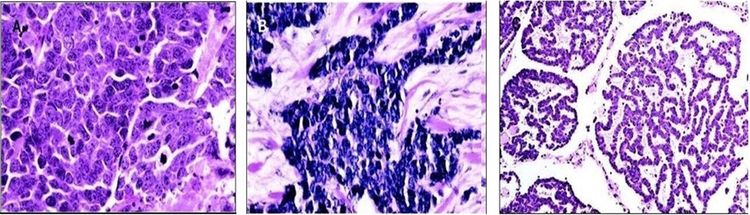

Characteristic histopathological features include dense core cytoplasmic neurosecretory granules on electron microscopy and cytokeratin-20 on immunohistochemistry (see Figure 4).[5]

A panel of immunoreagents (see Figure 4) can distinguish between Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) and other similar-appearing tumors including neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung (i.e., small cell carcinoma), lymphoma, peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor, metastatic carcinoid tumor, and small cell melanoma.[5]

Histologically, MCC has been classified into three distinct subtypes:[6-9]

- Trabecular: classic pattern, large-cell type, high density or granules on ultrasound examination.

- Intermediate: solid pattern (most common).

- Small cell: diffuse, few high-density granules on ultrasound examination (second most common).

Mixtures of variants are common.[6-8] Although some small retrospective case series have suggested correlations between certain histological features and outcome, the evidence remains uncertain.[10-12]

One group has suggested a list of 12 elements that should be described in pathology reports of resected primary lesions and nine elements to be described in pathology reports of sentinel lymph nodes. The prognostic significance of these elements has not been validated prospectively.[13]

If the following data are recorded for every patient with MCC, any patient can be staged with the existing or new staging system:

- Size of primary tumor (maximum dimension pathologically or clinically in centimeters).

- Presence/absence of primary tumor invasion into bone, muscle, fascia, or cartilage.

- Presence/absence of nodal metastasis.

- Method used to ascertain status of nodal involvement (clinical or pathological examination).

- Presence/absence of distant metastasis.

The College of American Pathologists has published a protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with MCC of the skin.[14]

For more information, see the Stage Information for Merkel Cell Carcinoma section.

The histological variants of MCC are shown in Figure 5. [15]

References

- Nghiem P, McKee PH, Haynes HA: Merkel cell (cutaneous neuroendocrine) carcinoma. In: Sober AJ, Haluska FG, eds.: Skin Cancer. BC Decker Inc., 2001, pp 127-141.

- Bichakjian CK, Nghiem P, Johnson T, et al.: Merkel Cell Carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp 549-62.

- Eng TY, Boersma MG, Fuller CD, et al.: A comprehensive review of the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol 30 (6): 624-36, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Medina-Franco H, Urist MM, Fiveash J, et al.: Multimodality treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: case series and literature review of 1024 cases. Ann Surg Oncol 8 (3): 204-8, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Busse PM, Clark JR, Muse VV, et al.: Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 19-2008. A 63-year-old HIV-positive man with cutaneous Merkel-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 358 (25): 2717-23, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Haag ML, Glass LF, Fenske NA: Merkel cell carcinoma. Diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Surg 21 (8): 669-83, 1995. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ratner D, Nelson BR, Brown MD, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 29 (2 Pt 1): 143-56, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gould VE, Moll R, Moll I, et al.: Neuroendocrine (Merkel) cells of the skin: hyperplasias, dysplasias, and neoplasms. Lab Invest 52 (4): 334-53, 1985. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population based study. J Cutan Pathol 37 (1): 20-7, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Alam M: Management of Merkel cell carcinoma: What we know. Arch Dermatol 142 (6): 771-4, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Heath ML, Nghiem P: Merkel cell carcinoma: if no breslow, then what? J Surg Oncol 95 (8): 614-5, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Andea AA, Coit DG, Amin B, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma: histologic features and prognosis. Cancer 113 (9): 2549-58, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bichakjian CK, Lowe L, Lao CD, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma: critical review with guidelines for multidisciplinary management. Cancer 110 (1): 1-12, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rao P, Balzer BL, Lemos BD, et al.: Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with merkel cell carcinoma of the skin. Arch Pathol Lab Med 134 (3): 341-4, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Goessling W, McKee PH, Mayer RJ: Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 20 (2): 588-98, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

Stage Information for Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Previously, five competing staging systems have been used to describe Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) in most publications.

| First Author | Publication Date | Institution(s) | No. of Patients in Case Series | Dates of Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSKCC = Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center; N/A = Not applicable. | ||||

| aThe MSKCC system has evolved over time. MSKCC authors have published one additional case series with 256 patients.[1] | ||||

| Yiengpruksawan [2] | 1991 | MSKCCa | 77 | 1969–1989 |

| Allen [3] | 1999 | MSKCCa | 102 | 1969–1996 |

| Allen [4] | 2005 | MSKCCa | 250 | 1970–2002 |

| American Joint Committee on Cancer [5] | 2017 | N/A | N/A | |

| Clark [6] | 2007 | Westmead Hospital, Sydney, Australia | 110 | |

| Princess Margaret Hospital/University Health Network, Toronto, Canada | ||||

| Sydney Head and Neck Cancer Institute/Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, Australia | ||||

These staging systems are highly inconsistent with each other. Stage III disease can mean anything from advanced local disease to nodal disease to distant metastatic disease. Furthermore, all MCC staging systems in use have been based on fewer than 300 patients.

American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Stage Groupings and TNM Definitions

To address these concerns, a new MCC-specific consensus staging system was developed by the AJCC to define MCC.[7] Before the publication of this new system, the AJCC advocated using the nonmelanoma staging system.

Cancers staged using this staging system include primary cutaneous neuroendocrine carcinoma (MCC).

Clinical Stage Group (cTNM)

| Stage | TNM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; c = clinical. | ||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Merkel Cell Carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 549–62. | ||

| 0 | Tis, N0, M0 | Tis = In situ primary tumor. |

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

| Stage | TNM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; c = clinical. | ||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Merkel Cell Carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 549–62. | ||

| I | T1, N0, M0 | T1 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter ≤2 cm. |

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

| Stage | TNM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; c = clinical. | ||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Merkel Cell Carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 549–62. | ||

| IIA | T2–3, N0, M0 | T2 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter >2 cm but ≤5 cm. |

| T3 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter >5 cm. | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

| IIB | T4, N0, M0 | T4 = Primary tumor invades fascia, muscle, cartilage, or bone. |

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

| Stage | TNM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; c = clinical. | ||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Merkel Cell Carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 549–62. | ||

| III | T0–4, N1–3, M0 | T0 = No evidence of primary tumor. |

| Tis = In situ primary tumor. | ||

| T1 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter ≤2 cm. | ||

| T2 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter >2 but ≤5 cm. | ||

| T3 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter >5 cm. | ||

| T4 = Primary tumor invades fascia, muscle, cartilage, or bone. | ||

| N1 = Metastasis in regional lymph node(s). | ||

| N2 = In-transit metastasis (discontinuous from primary tumor; located between primary tumor and draining regional nodal basin, or distal to the primary tumor) without lymph node metastasis. | ||

| N3 = In-transit metastasis (discontinuous from primary tumor; located between primary tumor and draining regional nodal basin, or distal to the primary tumor) with lymph node metastasis. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

| Stage | TNM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; c = clinical. | ||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Merkel Cell Carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 549–62. | ||

| IV | T0–4, Any N, M1 | T0 = No evidence of primary tumor. |

| Tis = In situ primary tumor. | ||

| T1 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter ≤2 cm. | ||

| T2 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter >2 but ≤5 cm. | ||

| T3 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter >5 cm. | ||

| T4 = Primary tumor invades fascia, muscle, cartilage, or bone. | ||

| NX = Regional lymph nodes cannot be clinically assessed (e.g., previously removed for another reason, or because of body habitus). | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

| N1 = Metastasis in regional lymph node(s). | ||

| N2 = In-transit metastasis (discontinuous from primary tumor; located between primary tumor and draining regional nodal basin, or distal to the primary tumor) without lymph node metastasis. | ||

| N3 = In-transit metastasis (discontinuous from primary tumor; located between primary tumor and draining regional nodal basin, or distal to the primary tumor) with lymph node metastasis. | ||

| M1 = Distant metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

Pathological Stage Group (pTNM)

| Stage | TNM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; p = pathological. | ||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Merkel Cell Carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 549–62. | ||

| 0 | Tis, pN0, M0 | Tis = In situ primary tumor. |

| pN0 = No regional lymph node metastasis detected on pathological evaluation. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

| Stage | TNM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; p = pathological. | ||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Merkel Cell Carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 549–62. | ||

| I | T1, pN0, M0 | T1 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter ≤2 cm. |

| pN0 = No regional lymph node metastasis detected on pathological evaluation. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

| Stage | TNM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; p = pathological. | ||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Merkel Cell Carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 549–62. | ||

| IIA | T2–3, pN0, M0 | T2 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter >2 but ≤5 cm. |

| T3 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter >5 cm. | ||

| pN0 = No regional lymph node metastasis detected on pathological evaluation. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

| IIB | T4, pN0, M0 | T4 = Primary tumor invades fascia, muscle, cartilage, or bone. |

| pN0 = No regional lymph node metastasis detected on pathological evaluation. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

| Stage | TNM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; p = pathological. | ||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Merkel Cell Carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 549–62. | ||

| IIIA | T1–4, pN1a(sn) or pN1a, M0 | T1 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter ≤2 cm. |

| T2 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter >2 cm but ≤5 cm. | ||

| T3 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter >5 cm. | ||

| T4 = Primary tumor invades fascia, muscle, cartilage, or bone. | ||

| pN1a(sn) = Clinically occult regional lymph node metastasis identified only by sentinel lymph node biopsy. | ||

| pN1a = Clinically occult regional lymph node metastasis following lymph node dissection. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

| T0, pN1b, M0 | T0 = No evidence of primary tumor. | |

| pN1b = Clinically and/or radiologically detected regional lymph node metastasis, microscopically confirmed. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

| IIIB | T1–4, pN1b–3, M0 | T1 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter ≤2 cm. |

| T2 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter >2 cm but ≤5 cm. | ||

| T3 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter >5 cm. | ||

| T4 = Primary tumor invades fascia, muscle, cartilage, or bone. | ||

| pN1b = Clinically and/or radiologically detected regional lymph node metastasis, microscopically confirmed. | ||

| pN2 = In-transit metastasis (discontinuous from primary tumor; located between primary tumor and draining regional nodal basin, or distal to the primary tumor) without lymph node metastasis. | ||

| pN3 = In-transit metastasis (discontinuous from primary tumor; located between primary tumor and draining regional nodal basin, or distal to the primary tumor) with lymph node metastasis. | ||

| M0 = No distant metastasis detected on clinical and/or radiologic examination. | ||

| Stage | TNM | Description |

|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph node; M = distant metastasis; p = pathological. | ||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Merkel Cell Carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 549–62. | ||

| IV | T0–4, Any pN, pM1 | T0 = No evidence of primary tumor. |

| T1 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter ≤2 cm. | ||

| T2 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter >2 cm but ≤5 cm. | ||

| T3 = Maximum clinical tumor diameter >5 cm. | ||

| T4 = Primary tumor invades fascia, muscle, cartilage, or bone. | ||

| pNX = Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed (e.g., previously removed for another reason or not removed for pathological evaluation). | ||

| pN0 = No regional lymph node metastasis detected on pathological evaluation. | ||

| pN1 = Metastasis in regional lymph node(s). | ||

| –pN1a(sn) = Clinically occult regional lymph node metastasis identified only by sentinel lymph node biopsy. | ||

| –pN1a = Clinically occult regional lymph node metastasis following lymph node dissection. | ||

| –pN1b = Clinically and/or radiologically detected regional lymph node metastasis, microscopically confirmed. | ||

| pN2 = In-transit metastasis (discontinuous from primary tumor; located between primary tumor and draining regional nodal basin, or distal to the primary tumor) without lymph node metastasis. | ||

| pN3 = In-transit metastasis (discontinuous from primary tumor; located between primary tumor and draining regional nodal basin, or distal to the primary tumor) with lymph node metastasis. | ||

| pM1 = Distant metastasis microscopically confirmed. | ||

| –pM1a = Metastasis to distant skin, distant subcutaneous tissue, or distant lymph node(s), microscopically confirmed. | ||

| –pM1b = Metastasis to lung, microscopically confirmed. | ||

| pM1c = Metastasis to all other distant sites, microscopically confirmed. | ||

Before the new AJCC consensus staging system was published, the most recent Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) four-stage system was favored because it was based on the largest number of patients and was the best validated.[1] The stages in the MSKCC system included:

- Stage I: local disease <2 cm.

- Stage II: local disease ≥2 cm.

- Stage III: regional nodal disease.

- Stage IV: distant metastatic disease.

One group has suggested a list of 12 elements that should be described in pathology reports of resected primary lesions and nine elements to be described in pathology reports of sentinel lymph nodes. The prognostic significance of these elements has not been validated prospectively.[8] The 2009 AJCC staging manual also specifies a variety of factors that should be collected prospectively on pathology reports.

References

- Andea AA, Coit DG, Amin B, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma: histologic features and prognosis. Cancer 113 (9): 2549-58, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Yiengpruksawan A, Coit DG, Thaler HT, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma. Prognosis and management. Arch Surg 126 (12): 1514-9, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Allen PJ, Zhang ZF, Coit DG: Surgical management of Merkel cell carcinoma. Ann Surg 229 (1): 97-105, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol 23 (10): 2300-9, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017.

- Clark JR, Veness MJ, Gilbert R, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma of the head and neck: is adjuvant radiotherapy necessary? Head Neck 29 (3): 249-57, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bichakjian CK, Nghiem P, Johnson T, et al.: Merkel Cell Carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp 549-62.

- Bichakjian CK, Lowe L, Lao CD, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma: critical review with guidelines for multidisciplinary management. Cancer 110 (1): 1-12, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment Option Overview for Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is an uncommon tumor. Most clinical management recommendations in the literature are based on case series that describe a relatively small number of patients who were not entered on formal clinical trials, evaluated with uniform clinical staging procedures, treated with uniform treatment protocols, or provided with regular, prescribed follow-up. These reports are also confounded by potential selection bias, referral bias, and short follow-up. They are underpowered to detect modest differences in outcome.

In addition, outcomes of patients with American Joint Committee on Cancer stage I and stage II disease are often reported together. In the absence of results from clinical trials with prescribed work-up, treatments, and follow-up, most patients with MCC have been treated using institutional or practitioner preferences that consider the specifics of each case as well as patient preference.

There are two competing philosophies about the most appropriate method of treating MCC. In the first philosophy, MCC is treated like other nonmelanoma skin cancers, with an emphasis on treating local-regional disease with surgery and radiation therapy, as appropriate. In the second philosophy, MCC is treated according to its biological features. This approach makes it analogous to small cell lung cancer, which is assumed to be a systemic disease, and leads to a more routine recommendation of systematic adjuvant chemotherapy.[1]

Surgery for the Primary Lesion

In a review of 18 case series, 279 of 926 patients (30.1%) developed local recurrence during follow-up, excluding those presenting with distant metastatic disease at presentation. These recurrences have been typically attributed to inadequate surgical margins or possibly a lack of adjuvant radiation therapy.[2,3]

Given the propensity of MCC to recur locally (sometimes with satellite lesions and/or in-transit metastases), wide local excision to reduce the risk of local recurrence has been recommended for patients with clinical stage I or stage II disease.

Recommendations about the optimal minimum width and depth of normal tissue margin to be excised around the primary tumor differ among the various retrospective case series, but this question has not been studied systematically.[3-7][Level of evidence C2] No definitive data suggest that extremely wide margins improve overall survival (OS), although some reports suggest that wider margins appear to improve local control.[3][Level of evidence C2] Frozen-section evaluation of margins may be useful, especially when the tumor is in an anatomical site that is not amenable to wide margins.

Some authors have advocated the use of Mohs micrographic surgery as a tissue-sparing technique. The relapse rate has been reported to be similar to or better than that of wide excision, but comparatively few cases have been treated in this manner and none in randomized controlled trials.[7-10][Level of evidence C2]

Regional Lymph Node Surgery

In some case series, local-regional recurrence rates are high when pathological nodal staging is omitted. Surgical nodal staging in clinically negative patients has identified positive nodes in at least 25% to 35% of patients.[4,11,12][Level of evidence C2] In one retrospective series of 213 patients who underwent surgical treatment of the primary tumor and evaluation of the draining nodes, nodal positivity was found in 2 of 54 patients with small tumors (e.g., ≤1.0 cm) and 51 of 159 patients with tumors larger than 1.0 cm.[13][Level of evidence C2]

The role of elective lymph node dissection (ELND) in the absence of clinically positive lymph nodes has not been studied in formal clinical trials. In small case series, ELND has been recommended for larger primary tumors, tumors with more than ten mitoses per high-power field, lymphatic or vascular invasion, and the small-cell histological subtypes.[14-16][Level of evidence C2]

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy has been suggested as a preferred initial alternative to complete ELND for the proper staging of MCC. SLN biopsy has less morbidity than complete nodal dissection. Furthermore, for MCC sites with indeterminate lymphatic drainage, such as those on the back, SLN biopsy techniques can be used to identify the pertinent lymph node bed(s). If performed, SLN biopsy is done at the time of the wide resection when the local lymphatic channels are still intact.

Several reports have found the use of SLN biopsy techniques in MCC to be reliable and reproducible.[17-20] However, the significance of SLN positivity remains unclear.

- One meta-analysis of ten case series found that SLN positivity strongly predicted a high short-term risk of recurrence and that subsequent therapeutic lymph node dissection was effective in preventing short-term regional nodal recurrence.[21]

- Another meta-analysis included 12 retrospective case series (only partially overlapping the collection of case series in the previous meta-analysis).[12][Level of evidence C2]

- SLN biopsy detected MCC spread in one-third of patients whose tumors would have otherwise been clinically and radiologically understaged.

- The recurrence rate was three times higher in patients with a positive SLN biopsy than in those with a negative SLN biopsy (P = .03).

- Between 2006 and 2010, a large, retrospective, single-institutional series of 95 patients (with a total of 97 primary tumors) identified a SLN in 93 instances, and nodal tumor was seen in 42 patients. Immunohistochemical techniques were used to assess node positivity. Various models of tumor and patient characteristics were studied to predict node positivity. There was no subgroup of patients predicted to have lower than 15% to 20% likelihood of SLN positivity, suggesting that SLN biopsy may be considered for all curative patients with clinically negative lymph nodes and no distant metastases.[22][Level of evidence C2]

- From 1996 to 2010, another retrospective single-institutional study of 153 patients with localized MCC who underwent SLN biopsy analyzed factors associated with SLN positivity. The best predictors of SLN biopsy positivity were tumor size and lymphovascular invasion.[22,23][Level of evidence C2]

In the absence of adequately powered, prospective, randomized clinical trials, the following questions remain:[4,12,21,24][Level of evidence C2]

- Should every positive SLN biopsy be followed routinely by completion nodal surgery and/or radiation therapy?

- Are outcomes demonstrably improved by routinely adding radiation if lymph node surgery reveals tumor in multiple nodes and/or extracapsular extension and/or lymphovascular invasion?

- Should patients with MCCs smaller than 1 cm routinely undergo sentinel lymph node dissection (SLND)?

- Should patients with negative or omitted nodal work-up routinely undergo local or local-regional radiation therapy?

- Should immunohistochemical staining techniques be used to identify micrometastases in lymph nodes, and is micrometastatic disease in nodes clinically relevant?

Lymph node surgery is primarily used for staging and guiding additional treatment.

Based on a small number of retrospective studies, therapeutic dissection of the regional lymph nodes after a positive SLND appears to minimize, but not totally eliminate, the risk of subsequent regional lymph node recurrence and in-transit metastases.[4,21,24][Level of evidence C2] There are no data from prospective randomized trials demonstrating that definitive regional nodal treatment with surgery improves survival.

Radiation Therapy

Because of the aggressive nature of MCC, its apparent radiosensitivity, and the high incidence of local and regional recurrences (including in-transit metastases after surgery alone to the primary tumor bed), some clinicians have recommended adjuvant radiation therapy to the primary site and nodal basin. Nodal basin radiation in contiguity with radiation to the primary site has been considered, especially for patients with larger tumors, locally unresectable tumors, close or positive excision margins that cannot be improved by additional surgery, and those with positive regional lymph nodes, especially after SLND (stage II).[10,11,14,15,25][Level of evidence C2] Several small retrospective series have shown that radiation therapy plus adequate surgery improves local-regional control compared with surgery alone,[2,5,26-29] whereas other series did not show the same results.[4,8][Level of evidence C2]

In the absence of adequately powered, prospective, randomized clinical trials, the following questions remain:[4,8,9,12,21,24,26,30-34][Level of evidence C2]

- Should every positive SLN biopsy be followed routinely by completion nodal surgery and/or radiation therapy?

- Are outcomes demonstrably improved by routinely adding radiation only if nodal surgery reveals tumor in multiple lymph nodes and/or extracapsular extension and/or lymphovascular invasion?

- Should all or just certain patients with negative or omitted nodal work-up receive local or local-regional radiation routinely?

Because of the small size of these nonrandomized retrospective series, the precise benefit from radiation therapy remains unproven.

When recommended, the radiation dose given has been at least 50 Gy to the surgical bed with margins and to the draining regional lymphatics, delivered in 2 Gy fractions. For patients with unresected tumors or tumors with microscopic evidence of spread beyond resected margins, higher doses of 56 Gy to 65 Gy to the primary site have been recommended.[5,10,11,14,15,27,31,35][Level of evidence C2] These doses have not been studied prospectively in clinical trials.

Local and/or regional control of MCC with radiation therapy alone has been reported in small, highly selected, nonrandomized case series of patients with diverse clinical characteristics.[29,36] Typically, these patients have had inoperable primary tumors and/or nodes or were considered medically inappropriate for surgery.[29,36][Level of evidence C2]

Retrospective Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program data suggest that adding radiation therapy to surgery adds survival value, but the conclusions are complicated by incomplete patient data, no protocol for evaluation and treatment, and potential sampling bias.[32] Prospective randomized clinical trials are required to assess whether combining surgery with radiation therapy affects survival.[33,34][Level of evidence C2]

Immunotherapy

Approximately 70% to 80% of MCC cases in the United States are caused by Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV). Within virus-positive MCCs, the viral oncoproteins (T antigens) are constitutively expressed and promote growth. Furthermore, patients with stimulated immune responses to MCPyV have better disease outcomes, providing a rationale for the use of immunotherapy. Although limited by a lack of randomized trials, several single-agent immune checkpoint inhibitors have shown improved survival and tolerability in patients with advanced MCC, compared with the chemotherapy that was used in historical controls. Therefore, immune checkpoint inhibitors are considered the recommended first-line treatment for most patients. There are ongoing trials to assess the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors in the neoadjuvant and adjuvant setting.

Avelumab

Avelumab is a human anti–programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) monoclonal antibody.

Evidence (avelumab):

- In a phase II trial (JAVELIN Merkel 200 [NCT02155647]), 88 patients with metastatic MCC received avelumab (10 mg/kg intravenously [IV] every 2 weeks). These patients had previously received chemotherapy.[37]

- The objective response rate was 33%, and 11% of patients had a complete response. The median time to response was 6.1 weeks and was irrespective of MCPyV or PD-L1 status. More importantly, responses were durable, with 74% lasting at least 1 year. The median OS was 12.6 months, more than twice the historical median with second-line chemotherapy.

Based on the results of this study, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved avelumab in 2017 for the treatment of patients with metastatic MCC, regardless of previous chemotherapy administration.[37-39]

- Avelumab was also studied in the first-line setting in a single-arm phase II trial of 116 patients.[40]

- After a median follow-up of 21.2 months, 30.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 22.0%–39.4%) of patients had a durable response (>6 months). The objective response rate was 39.7%, and the median OS was 20.3 months (95% CI, 12.4–not estimable).[40][Level of evidence C3]

- Exploratory analyses found that responses were higher in patients with PD-L1 expression and in those negative for MCPyV.

Pembrolizumab

Pembrolizumab is a humanized IgG4 anti–programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) monoclonal antibody.

Evidence (pembrolizumab):

- Pembrolizumab was studied in a phase II trial (NCT02267603) of first-line systemic treatment for patients with unresectable stage IIIB or stage IV MCC. A total of 50 patients received therapy.[41][Level of evidence C3]

- The objective response rate was 58% (95% CI, 43.2%–71.8%); 30% of patients had a complete response and 28% had a partial response. While the response rate was similar to historical rates with first-line chemotherapy, responses to pembrolizumab were more durable. The median progression-free survival (PFS) was 16.8 months (95% CI, 4.6–43.4), and the 3-year OS rate was 59.4%.

The FDA approved pembrolizumab in 2018.

Retifanlimab

Retifanlimab is an anti–PD-1 monoclonal antibody.

Evidence (retifanlimab):

- Retifanlimab was evaluated in a phase II trial (POD1UM-201 [NCT03599713]), published in abstract form, of 101 patients with previously untreated advanced MCC. Patients received 500mg intravenously (IV) every 4 weeks.[42,43]

- Preliminary results after a median follow up 17.6 months demonstrated a complete response rate of 16.8%, a partial response rate of 38.6%, and an overall response rate of 53.5% (95% CI, 43.3%–63.5%).[42,43][Level of evidence C3]

- The median PFS was 12.7 months (95% CI, 7.3–24.9) and the median duration of response was 25.3 months (95% CI, 14.2–not estimable). The median OS was not yet reached.

Based on the results of this trial, the FDA granted accelerated approval to retifanlimab in 2023.

Nivolumab

Nivolumab is an anti–PD-1 monoclonal antibody.

Evidence (nivolumab):

- Nivolumab was studied in a phase I/II trial (CheckMate 358 [NCT02488759]), published in abstract form, in patients with virus-associated cancers, including MCC. Patients may have received up to two prior lines of therapy. Patients with metastatic MCC were eligible regardless of MCPyV status or previous chemotherapy.[44,45]

- Data from 25 patients with metastatic disease demonstrated an overall response rate of 60% with a median treatment duration of 15.8 months. Preliminary results reported an ongoing response rate of 87%, with responses in 13 of 15 patients at last follow-up (median follow-up, 6 months).[44,45][Level of evidence C3]

- This trial added a second cohort to investigate nivolumab plus ipilimumab (1 mg/kg) in patients with metastatic MCC.

Nivolumab is not approved by the FDA for the treatment of MCC.

Chemotherapy

A variety of chemotherapy regimens have been used for patients with MCC in the adjuvant, advanced, and recurrent therapy settings.[5,34,46,47] [Level of evidence C2] No phase III clinical trials have been conducted to demonstrate that adjuvant chemotherapy produces improvements in OS. However, some clinicians recommend its use in most cases because of the following factors:

- A biological analogy is made between MCC and the histologically similar small cell carcinoma of the lung, which is considered a systemic disease.

- The risk of metastases and progression is high with MCC.

- Good initial clinical response rates have been noted with some chemotherapy regimens.

When possible, patients can be encouraged to participate in clinical trials.

From 1997 to 2001, the Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group performed a phase II evaluation of 53 patients with high-risk, local-regional MCC. High risk was defined as recurrence after initial therapy, involved lymph nodes, primary tumor larger than 1 cm, gross residual disease after surgery, or occult primary tumor with positive lymph nodes. Therapy included local-regional radiation therapy (50 Gy in 25 fractions), synchronous carboplatin (area under the curve [AUC], 4.5), and IV etoposide (89 mg/m2 on days 1–3 in weeks 1, 4, 7, and 10). Surgery was not standardized for either the primary tumor or the lymph nodes, and 12 patients had close margins, positive margins, or gross residual disease. Twenty-eight patients had undissected nodal beds, and the remainder had a variety of nodal surgeries. With a median follow-up of 48 months, the 3-year OS rate was 76%, the rate of local-regional control was 75%, and the rate of distant control was 76%. Radiation reactions in the skin and febrile neutropenia were significant clinical acute toxicities. Because of the heterogeneity of the population and the nonstandardized surgery, it is difficult to infer a clear treatment benefit from the chemotherapy.[48][Level of evidence C1]

In a subsequent report, the same investigators evaluated a subset of these protocol patients (n = 40, after excluding patients with unknown primary tumors). These patients were compared with 61 historical controls who received no chemotherapy, were treated at the same institutions, were diagnosed before 1997, and had no routine imaging staging studies. Radiation therapy was given to 50 patients. There was no significant survival benefit seen for chemotherapy patients.[49]

In a subsequent pilot clinical trial of 18 patients from 2004 to 2006, the same investigators attempted to reduce the skin and hematologic toxicity seen in Study 96-07. Carboplatin (AUC, 2) was administered weekly during radiation therapy beginning on day 1 for a maximum of five doses, followed by three cycles of carboplatin (AUC, 4.5; and IV etoposide 80 mg/m2 on days 1–3 beginning 3 weeks after radiation and repeated every 3 weeks for three cycles). The radiation therapy was similar to that in the earlier trial.[48] Results suggested a decrease in hematologic and skin toxicity.[50]

Use of chemotherapy has also been reported in selected patients with locally advanced and metastatic disease. In one retrospective study of 107 patients, 57% of patients with metastatic disease and 69% with locally advanced disease responded to initial chemotherapy. The median OS was 9 months for patients with metastatic disease and 24 months for patients with locally advanced disease. At 3 years, the OS rate was projected to be 17% for those with metastatic disease and 35% for those with locally advanced disease. Toxicity was significant, however, and without clear benefit, particularly in older patients.[51][Level of evidence C2]

Follow-Up

The most appropriate follow-up techniques and frequency for patients treated for MCC have not been prospectively studied. Because of the propensity for local and regional recurrence, clinicians should perform at least a thorough physical examination of the site of initial disease and the regional lymph nodes. Imaging studies may be ordered to evaluate signs and symptoms of concern, or they may be performed to identify distant metastases early. However, there are no data suggesting that early detection and treatment of new distant metastases results in improved survival.

In one series of 237 patients presenting with local or regional disease, the median time-to-recurrence was 9 months (range, 2–70 months). Ninety-one percent of recurrences occurred within 2 years of diagnosis.[4] It has been suggested that the intensity of follow-up can be gradually diminished after 2 to 3 years because most recurrences are likely to have already occurred.[4]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Busse PM, Clark JR, Muse VV, et al.: Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 19-2008. A 63-year-old HIV-positive man with cutaneous Merkel-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 358 (25): 2717-23, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Medina-Franco H, Urist MM, Fiveash J, et al.: Multimodality treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma: case series and literature review of 1024 cases. Ann Surg Oncol 8 (3): 204-8, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Nghiem P, James N: Merkel cell carcinoma. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al., eds.: Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill , 2008, pp 1087-94.

- Allen PJ, Bowne WB, Jaques DP, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma: prognosis and treatment of patients from a single institution. J Clin Oncol 23 (10): 2300-9, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Goessling W, McKee PH, Mayer RJ: Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 20 (2): 588-98, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Senchenkov A, Barnes SA, Moran SL: Predictors of survival and recurrence in the surgical treatment of merkel cell carcinoma of the extremities. J Surg Oncol 95 (3): 229-34, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Nghiem P, McKee PH, Haynes HA: Merkel cell (cutaneous neuroendocrine) carcinoma. In: Sober AJ, Haluska FG, eds.: Skin Cancer. BC Decker Inc., 2001, pp 127-141.

- Boyer JD, Zitelli JA, Brodland DG, et al.: Local control of primary Merkel cell carcinoma: review of 45 cases treated with Mohs micrographic surgery with and without adjuvant radiation. J Am Acad Dermatol 47 (6): 885-92, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wilson LD, Gruber SB: Merkel cell carcinoma and the controversial role of adjuvant radiation therapy: clinical choices in the absence of statistical evidence. J Am Acad Dermatol 50 (3): 435-7; discussion 437-8, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gollard R, Weber R, Kosty MP, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma: review of 22 cases with surgical, pathologic, and therapeutic considerations. Cancer 88 (8): 1842-51, 2000. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Eng TY, Boersma MG, Fuller CD, et al.: A comprehensive review of the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol 30 (6): 624-36, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gupta SG, Wang LC, Peñas PF, et al.: Sentinel lymph node biopsy for evaluation and treatment of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma: The Dana-Farber experience and meta-analysis of the literature. Arch Dermatol 142 (6): 685-90, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Stokes JB, Graw KS, Dengel LT, et al.: Patients with Merkel cell carcinoma tumors < or = 1.0 cm in diameter are unlikely to harbor regional lymph node metastasis. J Clin Oncol 27 (23): 3772-7, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Haag ML, Glass LF, Fenske NA: Merkel cell carcinoma. Diagnosis and treatment. Dermatol Surg 21 (8): 669-83, 1995. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ratner D, Nelson BR, Brown MD, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 29 (2 Pt 1): 143-56, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Yiengpruksawan A, Coit DG, Thaler HT, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma. Prognosis and management. Arch Surg 126 (12): 1514-9, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Messina JL, Reintgen DS, Cruse CW, et al.: Selective lymphadenectomy in patients with Merkel cell (cutaneous neuroendocrine) carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 4 (5): 389-95, 1997 Jul-Aug. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hill AD, Brady MS, Coit DG: Intraoperative lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy for Merkel cell carcinoma. Br J Surg 86 (4): 518-21, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wasserberg N, Schachter J, Fenig E, et al.: Applicability of the sentinel node technique to Merkel cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg 26 (2): 138-41, 2000. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rodrigues LK, Leong SP, Kashani-Sabet M, et al.: Early experience with sentinel lymph node mapping for Merkel cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 45 (2): 303-8, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mehrany K, Otley CC, Weenig RH, et al.: A meta-analysis of the prognostic significance of sentinel lymph node status in Merkel cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg 28 (2): 113-7; discussion 117, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schwartz JL, Griffith KA, Lowe L, et al.: Features predicting sentinel lymph node positivity in Merkel cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 29 (8): 1036-41, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Fields RC, Busam KJ, Chou JF, et al.: Recurrence and survival in patients undergoing sentinel lymph node biopsy for merkel cell carcinoma: analysis of 153 patients from a single institution. Ann Surg Oncol 18 (9): 2529-37, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Maza S, Trefzer U, Hofmann M, et al.: Impact of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with Merkel cell carcinoma: results of a prospective study and review of the literature. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 33 (4): 433-40, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Goepfert H, Remmler D, Silva E, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma (endocrine carcinoma of the skin) of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol 110 (11): 707-12, 1984. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lewis KG, Weinstock MA, Weaver AL, et al.: Adjuvant local irradiation for Merkel cell carcinoma. Arch Dermatol 142 (6): 693-700, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Veness MJ, Perera L, McCourt J, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma: improved outcome with adjuvant radiotherapy. ANZ J Surg 75 (5): 275-81, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jabbour J, Cumming R, Scolyer RA, et al.: Merkel cell carcinoma: assessing the effect of wide local excision, lymph node dissection, and radiotherapy on recurrence and survival in early-stage disease--results from a review of 82 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1992 and 2004. Ann Surg Oncol 14 (6): 1943-52, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Veness M, Foote M, Gebski V, et al.: The role of radiotherapy alone in patients with merkel cell carcinoma: reporting the Australian experience of 43 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 78 (3): 703-9, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Meeuwissen JA, Bourne RG, Kearsley JH: The importance of postoperative radiation therapy in the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 31 (2): 325-31, 1995. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Marks ME, Kim RY, Salter MM: Radiotherapy as an adjunct in the management of Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer 65 (1): 60-4, 1990. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mojica P, Smith D, Ellenhorn JD: Adjuvant radiation therapy is associated with improved survival in Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin. J Clin Oncol 25 (9): 1043-7, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Housman DM, Decker RH, Wilson LD: Regarding adjuvant radiation therapy in merkel cell carcinoma: selection bias and its affect on overall survival. J Clin Oncol 25 (28): 4503-4; author reply 4504-5, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Garneski KM, Nghiem P: Merkel cell carcinoma adjuvant therapy: current data support radiation but not chemotherapy. J Am Acad Dermatol 57 (1): 166-9, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Foote M, Harvey J, Porceddu S, et al.: Effect of radiotherapy dose and volume on relapse in Merkel cell cancer of the skin. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 77 (3): 677-84, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Fang LC, Lemos B, Douglas J, et al.: Radiation monotherapy as regional treatment for lymph node-positive Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer 116 (7): 1783-90, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kaufman HL, Russell JS, Hamid O, et al.: Updated efficacy of avelumab in patients with previously treated metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma after ≥1 year of follow-up: JAVELIN Merkel 200, a phase 2 clinical trial. J Immunother Cancer 6 (1): 7, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Becker JC, Lorenz E, Ugurel S, et al.: Evaluation of real-world treatment outcomes in patients with distant metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma following second-line chemotherapy in Europe. Oncotarget 8 (45): 79731-79741, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cowey CL, Mahnke L, Espirito J, et al.: Real-world treatment outcomes in patients with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma treated with chemotherapy in the USA. Future Oncol 13 (19): 1699-1710, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- D'Angelo SP, Lebbé C, Mortier L, et al.: First-line avelumab in a cohort of 116 patients with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma (JAVELIN Merkel 200): primary and biomarker analyses of a phase II study. J Immunother Cancer 9 (7): , 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Nghiem PT, Bhatia S, Lipson EJ, et al.: PD-1 Blockade with Pembrolizumab in Advanced Merkel-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 374 (26): 2542-52, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Grignani G, Rutkowski P, Lebbe C, et al.: Updated results from POD1UM-201: A phase II study of retifanlimab in patients with advanced or metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). [Abstract] Ann Oncol 34 (Suppl 2): A-1146P, S686, 2023.

- Grignani G, Rutkowski P, Lebbé C, et al.: Updated results from POD1UM-201: A phase 2 study of retifanlimab in patients with advanced or metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. In: Grignani G, Rutkowski P, Lebbe C, et al.: Updated results from POD1UM-201: A phase II study of retifanlimab in patients with advanced or metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). 34 (Suppl 2): A-1146P, S686, 2023, Poster. Available online. Last accessed May 9, 2025.

- Bhatia S, Topalian SL, Sharfman WH, et al.: Non-comparative, open-label, international, multicenter phase I/II study of nivolumab (NIVO) ± ipilimumab (IPI) in patients (pts) with recurrent/metastatic merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) (CheckMate 358). [Abstract] J Clin Oncol 41 (Suppl 16): A-9506, 2023.

- Topalian SL, Bhatia S, Hollebecque A, et al.: Abstract CT074: Non-comparative, open-label, multiple cohort, phase 1/2 study to evaluate nivolumab (NIVO) in patients with virus-associated tumors (CheckMate 358): efficacy and safety in Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). [Abstract] Cancer Res 77 (13 Suppl): A-CT074, 2017.

- Tai PT, Yu E, Winquist E, et al.: Chemotherapy in neuroendocrine/Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin: case series and review of 204 cases. J Clin Oncol 18 (12): 2493-9, 2000. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Henness S, Vereecken P: Management of Merkel tumours: an evidence-based review. Curr Opin Oncol 20 (3): 280-6, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Poulsen M, Rischin D, Walpole E, et al.: High-risk Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin treated with synchronous carboplatin/etoposide and radiation: a Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group Study--TROG 96:07. J Clin Oncol 21 (23): 4371-6, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Poulsen MG, Rischin D, Porter I, et al.: Does chemotherapy improve survival in high-risk stage I and II Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 64 (1): 114-9, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Poulsen M, Walpole E, Harvey J, et al.: Weekly carboplatin reduces toxicity during synchronous chemoradiotherapy for Merkel cell carcinoma of skin. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 72 (4): 1070-4, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Voog E, Biron P, Martin JP, et al.: Chemotherapy for patients with locally advanced or metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer 85 (12): 2589-95, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Stage I and II Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Stage I and II Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) include patients with local disease only.

Excision with 1 cm to 2 cm margins and radiation therapy are the mainstays of management for primary MCC tumors. Adjuvant radiation therapy to the primary tumor site is often recommended. However, the morbidity of radiation may be avoided and low local recurrence rates maintained, as shown in a subset of patients with small low-risk lesions (i.e., tumors <2 cm without other adverse prognostic factors).[1]

Because of the risk of occult nodal disease, sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy is recommended for patients without clinically detectable metastatic disease.[2] Any size of metastatic deposit is currently considered positive with regard to regional lymph node (N) staging; therefore, immunohistochemistry is routinely used to improve detection of micrometastases in SLN.[3,4]

Treatment Options for Stage I and II Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Treatment options for stage I and stage II MCC include:

- Margin-negative local excision, attempting to maintain function.

- Surgical nodal evaluation, typically by SLN procedure initially, may be considered for patients with significant risk of nodal disease. Completion of the nodal dissection may be considered if positive lymph nodes are found, which would upstage the patient's cancer to stage III.

- Local radiation therapy may be considered if there is concern about the primary tumor excision margins. Regional radiation therapy may be considered if the nodal staging procedure is incomplete or omitted. For sites where the location of primary regional lymph nodes may be uncertain (e.g., mid-back), regional-node field selection is problematic.

- Enrollment in clinical trials is encouraged.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References