Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version

General Information About Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML)

Incidence and Mortality

Estimated new cases and deaths from CML in the United States in 2025:[1]

- New cases: 9,560.

- Deaths: 1,290.

CML is one of a group of diseases called the myeloproliferative disorders. It is also called chronic myelogenous leukemia. Other related entities include:

- Polycythemia vera.

- Myelofibrosis.

- Essential thrombocythemia.

For more information, see Myeloproliferative Neoplasms Treatment.

Molecular Genetics

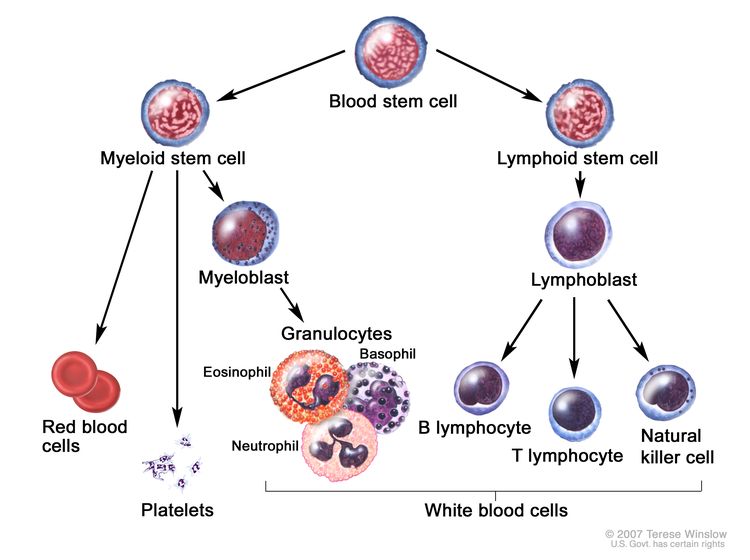

CML is identified by too many myeloblasts in the blood and bone marrow, and the disease worsens as the number of myeloblasts increase.

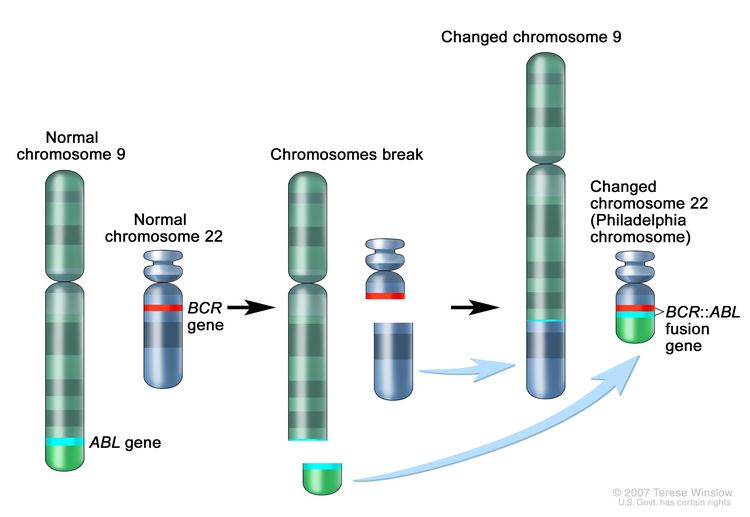

CML is a clonal disorder that is easily diagnosed because the leukemic cells of more than 95% of patients have a distinctive cytogenetic abnormality, the Philadelphia chromosome (Ph).[2]

The Ph chromosome results from a reciprocal translocation between the long arms of chromosomes 9 and 22, and it is demonstrable in all hematopoietic precursors.[3] This translocation results in the transfer of the ABL1 oncogene on chromosome 9 to an area of chromosome 22 termed the breakpoint cluster region (within the BCR gene).[3] This, in turn, results in a BCR::ABL1 fusion gene and in the production of an abnormal tyrosine kinase protein that causes the disordered myelopoiesis found in CML. Using peripheral blood, molecular techniques can detect the presence of the 9;22 translocation.

Clinical Presentation

Although CML may present without symptoms, splenomegaly is the most common finding during physical examination at the time of diagnosis.[4] The spleen may be enormous, filling most of the abdomen, causing pain or a feeling of fullness and presenting a significant clinical problem, or the spleen may be only minimally enlarged. In about 10% of patients, the spleen is neither palpable nor enlarged on computed tomography (CT) scan.

Patients may also present with the following symptoms:

- Fatigue.

- Unexplained weight loss.

- Drenching night sweats.

- Fever.

Transition between the chronic, accelerated, and blastic phases may occur gradually over 1 year or more, or it may occur abruptly (blast crisis). Patients with accelerated-phase CML show signs of progression without meeting the criteria for blast crisis (acute leukemia). The following signs and symptoms indicate a change to accelerated-phase CML:

- Progressive splenomegaly.

- Increased leukocytosis and/or thrombocytosis.

- Progressive anemia.

The following signs and symptoms indicate a change to a blast crisis, in addition to the accelerated-phase CML symptoms:

- Thrombocytopenia.

- Increasing and painful splenomegaly or hepatomegaly.

- Fever.

- Bone pain.

- Development of destructive bone lesions.

In the accelerated phase, differentiated cells persist, although they often show increasing morphological abnormalities. The patient experiences increased anemia, thrombocytopenia, and marrow fibrosis.[4]

Risk Factors

Risk factors for CML include:

- Older age.

- Exposure to high-dose ionizing radiation.

Diagnostic Evaluation

In addition to a health history and physical examination, the initial workup may include:

- Complete blood count with differential.

- Blood chemistry studies.

- Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy. In routine presentations of CML, the utility of bone marrow aspiration and biopsy for all newly diagnosed patients is questionable outside the context of a clinical trial. Bone marrow testing is appropriate for patients with clinical signs of accelerated phase or blast crisis (fever, enlarged spleen, or >20% blasts in the peripheral blood).[5]

- Cytogenetic analysis.

- Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). FISH of the BCR::ABL1 translocation can be performed using the bone marrow aspirate or peripheral blood of patients with CML.[4]

- Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). A small subset of patients has the BCR::ABL1 rearrangement detectable only by RT-PCR, which is the most sensitive technique currently available. Patients with RT-PCR evidence of the BCR::ABL1 fusion gene appear clinically and prognostically identical to patients with a classic Ph chromosome. However, patients who are BCR::ABL1-negative by RT-PCR have a clinical course more consistent with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, which is a distinct clinical entity related to myelodysplastic syndrome.[6-8]

- CT scan.

Prognosis and Survival

The median age of patients with Ph chromosome–positive CML is 67 years.[9] With the advent of the oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) , the median survival is projected to approach normal life expectancy for most patients.[10]

Ph chromosome–negative CML is a poorly defined entity that is less clearly distinguished from other myeloproliferative syndromes. Patients with Ph chromosome–negative CML generally have a poorer response to treatment and shorter survival than Ph chromosome–positive patients.[11] Ph chromosome–negative patients who have BCR::ABL1 gene rearrangements detectable by Southern blot analysis, however, have prognoses equivalent to Ph chromosome–positive patients.[6,12]

References

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2025. American Cancer Society, 2025. Available online. Last accessed January 16, 2025.

- Jabbour E, Kantarjian H: Chronic myeloid leukemia: 2020 update on diagnosis, therapy and monitoring. Am J Hematol 95 (6): 691-709, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Deininger MW, Goldman JM, Melo JV: The molecular biology of chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 96 (10): 3343-56, 2000. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jabbour E, Kantarjian H: Chronic myeloid leukemia: 2012 update on diagnosis, monitoring, and management. Am J Hematol 87 (11): 1037-45, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hidalgo-Lόpez JE, Kanagal-Shamanna R, Quesada AE, et al.: Bone marrow core biopsy in 508 consecutive patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: Assessment of potential value. Cancer 124 (19): 3849-3855, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Martiat P, Michaux JL, Rodhain J: Philadelphia-negative (Ph-) chronic myeloid leukemia (CML): comparison with Ph+ CML and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. The Groupe Français de Cytogénétique Hématologique. Blood 78 (1): 205-11, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Oscier DG: Atypical chronic myeloid leukaemia, a distinct clinical entity related to the myelodysplastic syndrome? Br J Haematol 92 (3): 582-6, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kurzrock R, Bueso-Ramos CE, Kantarjian H, et al.: BCR rearrangement-negative chronic myelogenous leukemia revisited. J Clin Oncol 19 (11): 2915-26, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lee SJ, Anasetti C, Horowitz MM, et al.: Initial therapy for chronic myelogenous leukemia: playing the odds. J Clin Oncol 16 (9): 2897-903, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bower H, Björkholm M, Dickman PW, et al.: Life Expectancy of Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Approaches the Life Expectancy of the General Population. J Clin Oncol 34 (24): 2851-7, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Onida F, Ball G, Kantarjian HM, et al.: Characteristics and outcome of patients with Philadelphia chromosome negative, bcr/abl negative chronic myelogenous leukemia. Cancer 95 (8): 1673-84, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cortes JE, Talpaz M, Beran M, et al.: Philadelphia chromosome-negative chronic myelogenous leukemia with rearrangement of the breakpoint cluster region. Long-term follow-up results. Cancer 75 (2): 464-70, 1995. [PUBMED Abstract]

Histopathology and Phases of CML

Histopathological examination of the bone marrow aspirate of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) demonstrates a shift in the myeloid series to immature forms that increase in number as patients progress to the blastic phase of the disease. The marrow is hypercellular, and differential counts of both marrow and blood show a spectrum of mature and immature granulocytes like that found in normal marrow. Increased numbers of eosinophils or basophils are often present, and monocytosis is sometimes seen. Increased megakaryocytes are often found in the marrow, and sometimes fragments of megakaryocytic nuclei are present in the blood, especially when the platelet count is very high. The percentage of lymphocytes is reduced in both the marrow and blood compared with normal samples. The myeloid:erythroid ratio in the marrow is usually greatly elevated. The leukocyte alkaline phosphatase enzyme is either absent or markedly reduced in the neutrophils of patients with CML.[1]

Most patients do not require bone marrow examination. However, bone marrow testing is appropriate for patients with fever, malaise, rapidly enlarging splenomegaly, and more than 10% circulating blasts. In patients with CML, bone marrow sampling is performed to assess cellularity, fibrosis, and cytogenetics. Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analyses using blood or marrow aspirates demonstrate the 9;22 translocation.[1]

Chronic-Phase CML

Chronic-phase CML is characterized by bone marrow and cytogenetic findings as listed below with less than 10% blasts and promyelocytes in the peripheral blood and bone marrow.[2] The following factors are predictive of a shorter chronic phase after treatment with tyrosine kinase inhibitors:

Predictive models using multivariate analysis have been derived.[5-7]

The rate of progression from chronic phase to blast crisis is 5% to 10% in the first 2 years and 20% in subsequent years.[5]

For more information, see the Treatment of Chronic-Phase CML section.

Accelerated-Phase CML

Accelerated-phase CML is characterized by 10% to 19% blasts in either the peripheral blood or bone marrow.[2]

For more information, see the Treatment of Accelerated-Phase CML section.

Blastic-Phase CML

Blastic-phase CML is characterized by 20% or more blasts in the peripheral blood or bone marrow.

When 20% or more blasts are present along with fever, malaise, and progressive splenomegaly, the patient has entered blast crisis.[2]

For more information, see the Treatment of Blastic-Phase CML section.

References

- Jabbour E, Kantarjian H: Chronic myeloid leukemia: 2012 update on diagnosis, monitoring, and management. Am J Hematol 87 (11): 1037-45, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cortes JE, Talpaz M, O'Brien S, et al.: Staging of chronic myeloid leukemia in the imatinib era: an evaluation of the World Health Organization proposal. Cancer 106 (6): 1306-15, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lauseker M, Bachl K, Turkina A, et al.: Prognosis of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia presenting in advanced phase is defined mainly by blast count, but also by age, chromosomal aberrations and hemoglobin. Am J Hematol 94 (11): 1236-1243, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Fabarius A, Leitner A, Hochhaus A, et al.: Impact of additional cytogenetic aberrations at diagnosis on prognosis of CML: long-term observation of 1151 patients from the randomized CML Study IV. Blood 118 (26): 6760-8, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sokal JE, Baccarani M, Russo D, et al.: Staging and prognosis in chronic myelogenous leukemia. Semin Hematol 25 (1): 49-61, 1988. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hasford J, Pfirrmann M, Hehlmann R, et al.: A new prognostic score for survival of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with interferon alfa. Writing Committee for the Collaborative CML Prognostic Factors Project Group. J Natl Cancer Inst 90 (11): 850-8, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kvasnicka HM, Thiele J, Schmitt-Graeff A, et al.: Bone marrow features improve prognostic efficiency in multivariate risk classification of chronic-phase Ph(1+) chronic myelogenous leukemia: a multicenter trial. J Clin Oncol 19 (12): 2994-3009, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment Option Overview for CML

Treatment of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) is usually initiated at diagnosis, which is based on the presence of an elevated white blood cell count, splenomegaly, thrombocytosis, and identification of the BCR::ABL1 translocation.[1]

| Phase | Treatment Options |

|---|---|

| BMT = bone marrow transplant; CML = chronic myeloid leukemia; SCT = stem cell transplant; TKIs = tyrosine kinase inhibitors. | |

| Chronic-phase CML | Targeted therapy with an allosteric inhibitor of BCR::ABL1 at the ABL1 myristoyl pocket |

| Targeted therapy with other BCR::ABL1 TKIs | |

| Allogeneic BMT or SCT | |

| Accelerated-phase CML | Targeted therapy with TKIs |

| Allogeneic SCT | |

| Blastic-phase CML | Targeted therapy with TKIs |

| Allogeneic BMT or SCT | |

| Relapsed CML | Targeted therapy with TKIs |

Targeted Therapy With Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs)

The optimal front-line treatment for patients with chronic-phase CML involves specific inhibitors of the BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase. Although imatinib mesylate has been extensively studied in patients with CML, TKIs with greater potency and selectivity for BCR::ABL1 than imatinib have also been evaluated.[1-4] Bariatric surgery may impede proper absorption of oral TKIs, resulting in suboptimal responses.[5]

Allogeneic Bone Marrow Transplant (BMT) or Stem Cell Transplant (SCT)

Allogeneic BMT or SCT has also been used with curative intent.[6] Long-term data beyond 10 years of therapy are available, and most long-term survivors show no evidence of the BCR::ABL1 translocation by any available test (e.g., cytogenetics, reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction, or fluorescence in situ hybridization). Some patients, however, are not eligible for this approach because of age, comorbid conditions, or lack of a suitable donor. In addition, substantial morbidity and mortality result from allogeneic BMT or SCT; a 5% to 10% treatment-related mortality can be expected, depending on whether a donor is related and the presence of mismatched antigens.[6]

Evidence (allogeneic SCT vs. drug treatment):

- In a prospective trial of 427 transplant-eligible, previously untreated patients, 166 patients were allocated to allogeneic SCT, and 261 patients were allocated to drug treatment (mostly imatinib).[6][Level of evidence C1]

- No difference in 10-year overall survival was reported between the treatment groups.

Similar outcomes were seen in patients who underwent allogeneic SCT because of TKI intolerance or nonadherence.[7]

Interferon Alfa

Long-term data are also available for patients treated with interferon alfa.[8-10] Approximately 10% to 20% of these patients have a complete cytogenetic response with no evidence of BCR::ABL1 translocation by any available test, and most of these patients are disease free beyond 10 years. Maintenance therapy with interferon is required, however, and some patients experience side effects that preclude continued treatment.

Hydroxyurea

Hydroxyurea is superior to busulfan in the chronic phase of CML, with significantly longer median survival and significantly fewer severe adverse effects.[11] A dose of 40 mg/kg per day is often used initially, and frequently results in a rapid reduction of the white blood cell (WBC) count. When the WBC count drops below 20 × 109/L, the hydroxyurea dose is often reduced and titrated to maintain a WBC count between 5 × 109/L and 20 × 109/L.

Hydroxyurea is used primarily to stabilize patients with hyperleukocytosis or as palliative therapy for patients who have not responded to other therapies.

References

- Cortes J, Pavlovsky C, Saußele S: Chronic myeloid leukaemia. Lancet 398 (10314): 1914-1926, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jabbour E, Kantarjian H: Chronic myeloid leukemia: 2020 update on diagnosis, therapy and monitoring. Am J Hematol 95 (6): 691-709, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Brümmendorf TH, Cortes JE, Milojkovic D, et al.: Bosutinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia: final results from the BFORE trial. Leukemia 36 (7): 1825-1833, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hochhaus A, Wang J, Kim DW, et al.: Asciminib in Newly Diagnosed Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med 391 (10): 885-898, 2024. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Haddad FG, Kantarjian HM, Bidikian A, et al.: Association between bariatric surgery and outcomes in chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer 129 (12): 1866-1872, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gratwohl A, Pfirrmann M, Zander A, et al.: Long-term outcome of patients with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia: a randomized comparison of stem cell transplantation with drug treatment. Leukemia 30 (3): 562-9, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wu J, Chen Y, Hageman L, et al.: Late mortality after bone marrow transplant for chronic myelogenous leukemia in the context of prior tyrosine kinase inhibitor exposure: A Blood or Marrow Transplant Survivor Study (BMTSS) report. Cancer 125 (22): 4033-4042, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ozer H, George SL, Schiffer CA, et al.: Prolonged subcutaneous administration of recombinant alpha 2b interferon in patients with previously untreated Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic-phase chronic myelogenous leukemia: effect on remission duration and survival: Cancer and Leukemia Group B study 8583. Blood 82 (10): 2975-84, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kantarjian HM, Smith TL, O'Brien S, et al.: Prolonged survival in chronic myelogenous leukemia after cytogenetic response to interferon-alpha therapy. The Leukemia Service. Ann Intern Med 122 (4): 254-61, 1995. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Long-term follow-up of the Italian trial of interferon-alpha versus conventional chemotherapy in chronic myeloid leukemia. The Italian Cooperative Study Group on Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 92 (5): 1541-8, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hehlmann R, Heimpel H, Hasford J, et al.: Randomized comparison of busulfan and hydroxyurea in chronic myelogenous leukemia: prolongation of survival by hydroxyurea. The German CML Study Group. Blood 82 (2): 398-407, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Chronic-Phase CML

Treatment Options for Chronic-Phase CML

Treatment options for chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) include:

- Targeted therapy with an allosteric inhibitor of BCR::ABL1 at the ABL1 myristoyl pocket (asciminib).

- Targeted therapy with other BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (nilotinib, dasatinib, bosutinib, or imatinib).

- Allogeneic bone marrow transplant (BMT) or stem cell transplant (SCT).

The preferred initial treatment for patients with newly diagnosed chronic-phase CML could be any of the specific inhibitors of the BCR::ABL1 tyrosine kinase (including asciminib, nilotinib, dasatinib, bosutinib, or imatinib).[1] With any of these agents, the 10-year event-free survival and overall survival (OS) rates exceed 90%.[2-4]

CML response rate abbreviations used in this section include:

- DMR: Deep molecular response (previously called CMR [complete molecular response]). This means greater than 4-log reduction (BCR::ABL1 ≤ 0.01%) and is also called MR 4 (molecular response 4). MR 4.5 is designated for BCR::ABL1 ≤ 0.0032%, and MR 5 is designated for BCR::ABL1 ≤ 0.001%.

- EMR: Early molecular response. This means a greater than 1-log reduction (BCR::ABL1 ≤ 10%) at 3 months.

- MMR: Major molecular response. This means a greater than 3-log reduction (BCR::ABL1 ≤ 0.1%).

A BCR::ABL1 transcript level of 10% or less in patients after 3 months of treatment with a specific TKI (deemed EMR) is associated with the best prognosis in terms of failure-free survival, progression-free survival (PFS), and OS.[5-10] However, in a retrospective analysis, even patients with a BCR::ABL1 transcript level greater than 10% after 3 months of therapy did well when the halving time was less than 76 days.[11]

Mandating a change of therapy based on this 10% transcript level at 3 to 6 months is problematic because 75% of patients do well even with a suboptimal response.[12] After 1 year, the preferred response target is an MMR, which is defined as a BCR::ABL1 level of less than or equal to 0.1%. The optimal target is a DMR, which is defined as under 4 logs (BCR::ABL1 ≤ 0.01%) or undetectable, which is usually a BCR::ABL1 level of less than or equal to 0.001% (MR 5).[13]

Targeted therapy with an allosteric inhibitor of BCR::ABL1 at the ABL1 myristoyl pocket

Evidence (targeted therapy with an allosteric inhibitor of BCR::ABL1 at the ABL1 myristoyl pocket):

- A prospective study (NCT04971226) included 405 patients with newly diagnosed CML. Patients were randomly assigned to receive asciminib (n = 201) (an allosteric inhibitor of BCR::ABL1 at the ABL1 myristoyl pocket, a site unique from those used by other TKIs) or either imatinib mesylate (n = 102) or nilotinib, dasatinib, or bosutinib (n = 102).[14]

- With a median follow-up of 16.3 months, the 48-week MMR rate was 67.7% for patients who received asciminib and 49% for patients who received imatinib, nilotinib, dasatinib, or bosutinib (P < .002).[14][Level of evidence B3]

- Patients who received asciminib had fewer grade 3 or greater adverse events (38%) compared with imatinib (44%) and the other TKIs (55%). The rate of discontinuation due to adverse events was lower for patients who received asciminib (5%) compared with patients who received imatinib (11%) or the other TKIs (10%).

- Asciminib showed improved efficacy in this early reporting of the trial, and it also showed better tolerability based on adverse events and discontinuations. On this basis, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the use of asciminib as first-line therapy. Use of asciminib will pose significant financial toxicity ($260,000 per year in 2024) versus imatinib ($500 per year in 2024). The price of the other TKIs may decrease because dasatinib is available as a generic, and nilotinib, bosutinib, and ponatinib are expected to be released as generics in 2027.

- A prespecified subgroup analysis compared asciminib with the second-generation TKIs (not including imatinib). At week 48, 66.0% of patients who received asciminib had an MMR, and 57.8% of patients who received second-generation TKIs had an MMR. The 8.2% difference was not statistically significant (95% confidence interval [CI], -5.1 to 21.5). In the first year, it appears that the efficacy of asciminib is equivalent to those of second-generation TKIs. Longer follow-up is required to fully assess efficacy and toxicity outcomes.[14]

Targeted therapy with other BCR::ABL1 TKIs

Evidence (targeted therapy with other BCR::ABL1 TKIs):

- A randomized prospective study of 846 patients compared nilotinib with imatinib.[15][Level of evidence B3]

- The rate of MMR at 24 months was 71% and 67% for patients who received two-dose schedules of nilotinib and 44% for patients who received imatinib (P < .0001 for both comparisons).

- Progression to accelerated-phase CML or blast crisis occurred in 17 patients who received imatinib (14%), but this progression only occurred in two patients who received nilotinib 300 mg twice daily (<1%, P = .0003) and in five patients who received nilotinib 400 mg twice daily (1.8%, P = .0089).

- A randomized prospective study of 519 patients compared dasatinib with imatinib, with the following results:[16][Level of evidence B3]

- The rate of MMR at 12 months was 46% for patients who received dasatinib and 28% for patients who received imatinib (P < .0001).

- The rate of MMR at 24 months was 64% for patients who received dasatinib and 46% for patients who received imatinib (P < .0001).

- At 5 years, there was no difference in PFS or OS.

- Progression to accelerated-phase CML or blast crisis occurred in 13 patients (5%) who received imatinib and in six patients (2.3%) who received dasatinib (not statistically significant).

- In retrospective comparative analyses, a dasatinib dose of 50 mg a day showed equal efficacy to 100 mg, but resulted in fewer pleural effusions (5% vs. 21%).[17][Level of evidence C3]

- A randomized prospective study of 536 patients compared bosutinib with imatinib.[18][Level of evidence B3]

- The MMR rate at 5 years was 73.9% for patients in the bosutinib arm versus 64.6% for patients in the imatinib arm (hazard ratio [HR], 1.57; 95% CI, 1.08–2.28; P = .0075). At 5 years, a DMR (4.5 logs) was attained by 47.4% of patients in the bosutinib arm and 36.6% of patients in the imatinib arm (HR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.11–2.22).[18]

- Progression to accelerated-phase CML or blast crisis occurred in four patients (1.6%) who received bosutinib and in six patients (2.5%) who received imatinib.

In randomized prospective trials, nilotinib, dasatinib, and bosutinib showed higher rates of earlier MMR compared with imatinib. It is unclear whether this will translate to improved long-term outcomes.[8,9,18][Level of evidence B3] A dose-ranging phase II study of dasatinib in patients older than 70 years showed optimal response and reduction of toxicity starting at 20 mg once daily (with dose escalation if needed), versus the standard dose of 100 mg daily.[19][Level of evidence C3]

Can TKIs be discontinued?

For patients who obtain a DMR, it is unclear if TKI therapy can be discontinued. Several nonrandomized reports are summarized as follows:[20-24][Level of evidence C3]

- Patients who have taken a TKI for more than 3 to 5 years and attained a DMR (molecular remission, 4.5; BCR::ABL1 ≤ 0.0032%) are the best candidates to consider stopping therapy.

- 50% of patients will experience a relapse of their disease if they discontinue TKI therapy. However, a retrospective analysis with a median follow-up of 3 years found that patients who were in DMR (4 to 4.5 logs) for 5 or more years had a relapse rate of approximately 10%.[25][Level of evidence C3] Another retrospective report with a median of 3 years of follow-up found three measurable factors predictive of MMR maintenance: increased duration of TKI treatment, increased duration of DMR on TKI treatment, and the absence of any peripheral blood blast cells at diagnosis.[20]

- Almost all patients who relapse based on BCR::ABL1 quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing can be successfully reinduced with the previous TKI.

However, after the reinduction of a previous TKI, the duration of remissions or the depth of responses are not known. Data to recommend universal discontinuation of TKIs are insufficient, even in patients with a DMR or CMR. Follow-up (i.e., at least every 3 months initially, although the precise interval is not well-defined) is required after stopping therapy because relapses have been noted even after 2 to 3 years. A withdrawal syndrome of muscle and joint pain has been reported after discontinuing TKI therapy.[26] Quality-of-life assessments suggest improved social function, diarrhea, and fatigue after stopping TKI therapy.[27][Level of evidence C1]

Allogeneic BMT or SCT

Allogeneic BMT or SCT is the only consistently successful curative treatment for patients with CML.[28-30] Patients younger than 60 years with an identical twin or with HLA–matched siblings can consider BMT early in the chronic phase. Although the procedure is associated with considerable acute morbidity and mortality, 50% to 70% of patients who undergo transplant in the chronic phase appear to be cured. The results are better in younger patients, especially for those younger than 20 years. The outcomes of patients who undergo transplant in the accelerated and blastic phases of the disease are progressively worse.[31,32] Most transplant series suggest improved survival when the procedure is performed within 1 year of diagnosis.[33-35][Level of evidence C1] The data supporting early transplant, however, have never been confirmed in controlled trials.

Evidence (allogeneic SCT):

- In a randomized clinical trial, patients underwent allogeneic SCT after receiving preparative therapy with

either cyclophosphamide and total-body irradiation (TBI) or busulfan and

cyclophosphamide without TBI. The following results were reported:[36][Level of evidence A1]

- Disease-free survival and OS were comparable between arms.

- Busulfan and cyclophosphamide without TBI was associated with less graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) and fewer fevers, hospitalizations, and hospital days.

- A retrospective review of 2,444 patients who underwent myeloablative allogeneic SCT reported the following:[37]

- The 15-year OS rates were 88% (95% CI, 86%–90%) for sibling-matched transplant recipients and 87% (95% CI, 83%–90%) for unrelated-donor transplant recipients.

- The cumulative incidences of relapse were 8% (95% CI, 7%–10%) for sibling-matched transplant recipients and 2% (95% CI, 1%– 4%) for unrelated-donor transplant recipients.

- In a prospective trial of 354 patients younger than 60 years, 123 of 135 patients with a matched, related donor underwent early allogeneic SCT while the others received interferon-based therapy and imatinib at relapse. Some patients also underwent a matched unrelated-donor SCT in remission.[38][Level of evidence B4]

- With a 9-year median follow-up, survival still favored the drug treatment arm (P = .049), but most of the benefit was early from transplant-related mortality, with the survival curves converging by 8 years.

Although most relapses occur within 5 years of transplant, relapses have occurred as late as 15 years after a BMT.[39] In a molecular analysis of 243 patients who underwent allogeneic BMT over a 20-year interval, only 15% had no detectable BCR::ABL1 transcript by PCR analysis.[40] The risk of relapse appears to be less in patients who underwent transplant early in disease and in patients who developed chronic GVHD.[32,41] In a retrospective review, patients with relapsed disease after allogeneic transplant who received TKI therapy had a 3-year OS rate of 60%.[42][Level of evidence C1]

With the introduction of asciminib, imatinib, dasatinib, bosutinib, and nilotinib therapy, the timing and sequence of allogeneic BMT or SCT has been questioned.[43] Allogeneic SCT is the preferred choice for certain patients presenting with blastic-phase disease, those with a T315I variant and resistance to ponatinib (an oral TKI), and for patients with complete intolerance to the pharmacological options.[44] Similar outcomes were seen in patients who underwent allogeneic SCT because of TKI intolerance or nonadherence.[45]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Wei G, Rafiyath S, Liu D: First-line treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia: dasatinib, nilotinib, or imatinib. J Hematol Oncol 3: 47, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hochhaus A, Larson RA, Guilhot F, et al.: Long-Term Outcomes of Imatinib Treatment for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med 376 (10): 917-927, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Masarova L, Cortes JE, Patel KP, et al.: Long-term results of a phase 2 trial of nilotinib 400 mg twice daily in newly diagnosed patients with chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer 126 (7): 1448-1459, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Maiti A, Cortes JE, Patel KP, et al.: Long-term results of frontline dasatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer 126 (7): 1502-1511, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Marin D, Ibrahim AR, Lucas C, et al.: Assessment of BCR-ABL1 transcript levels at 3 months is the only requirement for predicting outcome for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Clin Oncol 30 (3): 232-8, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Branford S, Kim DW, Soverini S, et al.: Initial molecular response at 3 months may predict both response and event-free survival at 24 months in imatinib-resistant or -intolerant patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase treated with nilotinib. J Clin Oncol 30 (35): 4323-9, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Marin D, Hedgley C, Clark RE, et al.: Predictive value of early molecular response in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with first-line dasatinib. Blood 120 (2): 291-4, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jabbour E, Kantarjian HM, Saglio G, et al.: Early response with dasatinib or imatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia: 3-year follow-up from a randomized phase 3 trial (DASISION). Blood 123 (4): 494-500, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hughes TP, Saglio G, Kantarjian HM, et al.: Early molecular response predicts outcomes in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase treated with frontline nilotinib or imatinib. Blood 123 (9): 1353-60, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Neelakantan P, Gerrard G, Lucas C, et al.: Combining BCR-ABL1 transcript levels at 3 and 6 months in chronic myeloid leukemia: implications for early intervention strategies. Blood 121 (14): 2739-42, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Branford S, Yeung DT, Parker WT, et al.: Prognosis for patients with CML and >10% BCR-ABL1 after 3 months of imatinib depends on the rate of BCR-ABL1 decline. Blood 124 (4): 511-8, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Baccarani M, Deininger MW, Rosti G, et al.: European LeukemiaNet recommendations for the management of chronic myeloid leukemia: 2013. Blood 122 (6): 872-84, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Shanmuganathan N, Hughes TP: Molecular monitoring in CML: how deep? How often? How should it influence therapy? Blood 132 (20): 2125-2133, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hochhaus A, Wang J, Kim DW, et al.: Asciminib in Newly Diagnosed Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. N Engl J Med 391 (10): 885-898, 2024. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kantarjian HM, Hochhaus A, Saglio G, et al.: Nilotinib versus imatinib for the treatment of patients with newly diagnosed chronic phase, Philadelphia chromosome-positive, chronic myeloid leukaemia: 24-month minimum follow-up of the phase 3 randomised ENESTnd trial. Lancet Oncol 12 (9): 841-51, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cortes JE, Saglio G, Kantarjian HM, et al.: Final 5-Year Study Results of DASISION: The Dasatinib Versus Imatinib Study in Treatment-Naïve Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Patients Trial. J Clin Oncol 34 (20): 2333-40, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jabbour E, Sasaki K, Haddad FG, et al.: Low-dose dasatinib 50 mg/day versus standard-dose dasatinib 100 mg/day as frontline therapy in chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase: A propensity score analysis. Am J Hematol 97 (11): 1413-1418, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Brümmendorf TH, Cortes JE, Milojkovic D, et al.: Bosutinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia: final results from the BFORE trial. Leukemia 36 (7): 1825-1833, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Murai K, Ureshino H, Kumagai T, et al.: Low-dose dasatinib in older patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia in chronic phase (DAVLEC): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol 8 (12): e902-e911, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mahon FX, Pfirrmann M, Dulucq S, et al.: European Stop Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Trial (EURO-SKI) in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: Final Analysis and Novel Prognostic Factors for Treatment-Free Remission. J Clin Oncol 42 (16): 1875-1880, 2024. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mahon FX, Boquimpani C, Kim DW, et al.: Treatment-Free Remission After Second-Line Nilotinib Treatment in Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in Chronic Phase: Results From a Single-Group, Phase 2, Open-Label Study. Ann Intern Med 168 (7): 461-470, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Legros L, Nicolini FE, Etienne G, et al.: Second tyrosine kinase inhibitor discontinuation attempt in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer 123 (22): 4403-4410, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Chamoun K, Kantarjian H, Atallah R, et al.: Tyrosine kinase inhibitor discontinuation in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia: a single-institution experience. J Hematol Oncol 12 (1): 1, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Atallah E, Schiffer CA, Radich JP, et al.: Assessment of Outcomes After Stopping Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Among Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: A Nonrandomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 7 (1): 42-50, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Haddad FG, Sasaki K, Issa GC, et al.: Treatment-free remission in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia following the discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Am J Hematol 97 (7): 856-864, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Richter J, Söderlund S, Lübking A, et al.: Musculoskeletal pain in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia after discontinuation of imatinib: a tyrosine kinase inhibitor withdrawal syndrome? J Clin Oncol 32 (25): 2821-3, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schoenbeck KL, Atallah E, Lin L, et al.: Patient-Reported Functional Outcomes in Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia After Stopping Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. J Natl Cancer Inst 114 (1): 160-164, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gratwohl A, Hermans J: Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia. Working Party Chronic Leukemia of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Bone Marrow Transplant 17 (Suppl 3): S7-9, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Crawley C, Szydlo R, Lalancette M, et al.: Outcomes of reduced-intensity transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia: an analysis of prognostic factors from the Chronic Leukemia Working Party of the EBMT. Blood 106 (9): 2969-76, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bacher U, Klyuchnikov E, Zabelina T, et al.: The changing scene of allogeneic stem cell transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia--a report from the German Registry covering the period from 1998 to 2004. Ann Hematol 88 (12): 1237-47, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wagner JE, Zahurak M, Piantadosi S, et al.: Bone marrow transplantation of chronic myelogenous leukemia in chronic phase: evaluation of risks and benefits. J Clin Oncol 10 (5): 779-89, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Enright H, Davies SM, DeFor T, et al.: Relapse after non-T-cell-depleted allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for chronic myelogenous leukemia: early transplantation, use of an unrelated donor, and chronic graft-versus-host disease are protective. Blood 88 (2): 714-20, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Goldman JM, Szydlo R, Horowitz MM, et al.: Choice of pretransplant treatment and timing of transplants for chronic myelogenous leukemia in chronic phase. Blood 82 (7): 2235-8, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Clift RA, Appelbaum FR, Thomas ED: Treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia by marrow transplantation. Blood 82 (7): 1954-6, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hansen JA, Gooley TA, Martin PJ, et al.: Bone marrow transplants from unrelated donors for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 338 (14): 962-8, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Clift RA, Buckner CD, Thomas ED, et al.: Marrow transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia: a randomized study comparing cyclophosphamide and total body irradiation with busulfan and cyclophosphamide. Blood 84 (6): 2036-43, 1994. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Goldman JM, Majhail NS, Klein JP, et al.: Relapse and late mortality in 5-year survivors of myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia in first chronic phase. J Clin Oncol 28 (11): 1888-95, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hehlmann R, Berger U, Pfirrmann M, et al.: Drug treatment is superior to allografting as first-line therapy in chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood 109 (11): 4686-92, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Maziarz R: Transplantation for CML: lifelong PCR monitoring? Blood 107 (10): 3820, 2006.

- Kaeda J, O'Shea D, Szydlo RM, et al.: Serial measurement of BCR-ABL transcripts in the peripheral blood after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for chronic myeloid leukemia: an attempt to define patients who may not require further therapy. Blood 107 (10): 4171-6, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Pichert G, Roy DC, Gonin R, et al.: Distinct patterns of minimal residual disease associated with graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for chronic myelogenous leukemia. J Clin Oncol 13 (7): 1704-13, 1995. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Shimazu Y, Murata M, Kondo T, et al.: The new generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor improves the survival of chronic myeloid leukemia patients after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Hematol Oncol 40 (3): 442-456, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Saussele S, Lauseker M, Gratwohl A, et al.: Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo SCT) for chronic myeloid leukemia in the imatinib era: evaluation of its impact within a subgroup of the randomized German CML Study IV. Blood 115 (10): 1880-5, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- O'Brien S, Berman E, Moore JO, et al.: NCCN Task Force report: tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy selection in the management of patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 9 (Suppl 2): S1-25, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wu J, Chen Y, Hageman L, et al.: Late mortality after bone marrow transplant for chronic myelogenous leukemia in the context of prior tyrosine kinase inhibitor exposure: A Blood or Marrow Transplant Survivor Study (BMTSS) report. Cancer 125 (22): 4033-4042, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Accelerated-Phase CML

Treatment Options for Accelerated-Phase CML

Treatment options for accelerated-phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) include:

Targeted therapy with TKIs

Bosutinib

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved bosutinib as a first-line treatment for patients with accelerated-phase CML. These patients were included in the initial phase I/II trial that showed improved efficacy versus imatinib, based on response rates and major molecular response at 5 years of follow-up.[1][Level of evidence C3]

Allogeneic SCT

Induction of remission using a TKI and consideration of an allogeneic SCT for patients with poor responses, when feasible, is a standard approach for patients with accelerated-phase CML.[2]

Evidence (imatinib vs. allogeneic SCT):

- A cohort study of 132 patients with accelerated-phase CML compared imatinib with allogeneic SCT as first-line therapy, with a median follow-up of 32 months.[2][Level of evidence C1]

- The overall survival rate was improved using allogeneic SCT for the Sokal high-risk patients (100% vs. 17.7%; P = .008).

- For Sokal low- and intermediate-risk patients, there were no survival differences between the two first-line approaches.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Gambacorti-Passerini C, Cortes JE, Lipton JH, et al.: Safety and efficacy of second-line bosutinib for chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia over a five-year period: final results of a phase I/II study. Haematologica 103 (8): 1298-1307, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jiang Q, Xu LP, Liu DH, et al.: Imatinib mesylate versus allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in the accelerated phase. Blood 117 (11): 3032-40, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Blastic-Phase CML

Treatment Options for Blastic-Phase CML

Treatment options for blastic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) include:

Targeted therapy with TKIs

Bosutinib, imatinib mesylate, dasatinib, and nilotinib have demonstrated activity in patients with myeloid blast crisis and lymphoid blast crisis or Philadelphia (Ph) chromosome–positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL).[1-3]

Evidence (targeted therapy with TKIs):

- Two trials of imatinib mesylate and one trial of dasatinib involved a total of 518 patients with blastic-phase CML.[2,4,5][Level of evidence C1]

- The studies confirmed a hematologic response rate of 42% to 55% and a major cytogenetic response rate of 16% to 25%, but the estimated 2-year survival rate was below 28%.

- Patients with lymphoid blastic-phase CML (as opposed to the more common myeloid blastic phase) have been given the same therapy as patients with Ph chromosome–positive ALL. In a phase II trial, 23 patients with lymphoid blastic-phase CML received hyper-CVAD (hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone) and dasatinib. The major molecular response rate was 70%, and most patients were referred for allogeneic SCT.[6][Level of evidence C3]

- A review of 477 patients with blastic-phase CML treated between 1997 and 2016 at a single center showed that 72% had received previous TKI therapy in chronic phase before transformation.[7][Level of evidence C3]

- The median overall survival was 12 months.

- The median failure-free survival was 5 months.

- Patients who could complete an allogeneic SCT fared best, but this may have resulted from selection bias.

Allogeneic BMT or SCT

Allogeneic BMT or SCT should be considered when feasible, depending on response and durability of response.[8-12]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Druker BJ, Sawyers CL, Kantarjian H, et al.: Activity of a specific inhibitor of the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase in the blast crisis of chronic myeloid leukemia and acute lymphoblastic leukemia with the Philadelphia chromosome. N Engl J Med 344 (14): 1038-42, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Saglio G, Hochhaus A, Goh YT, et al.: Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant or imatinib-intolerant chronic myeloid leukemia in blast phase after 2 years of follow-up in a phase 3 study: efficacy and tolerability of 140 milligrams once daily and 70 milligrams twice daily. Cancer 116 (16): 3852-61, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gambacorti-Passerini C, Cortes JE, Lipton JH, et al.: Safety and efficacy of second-line bosutinib for chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia over a five-year period: final results of a phase I/II study. Haematologica 103 (8): 1298-1307, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kantarjian HM, Cortes J, O'Brien S, et al.: Imatinib mesylate (STI571) therapy for Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia in blast phase. Blood 99 (10): 3547-53, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sawyers CL, Hochhaus A, Feldman E, et al.: Imatinib induces hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in myeloid blast crisis: results of a phase II study. Blood 99 (10): 3530-9, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Morita K, Kantarjian HM, Sasaki K, et al.: Outcome of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in lymphoid blastic phase and Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with hyper-CVAD and dasatinib. Cancer 127 (15): 2641-2647, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jain P, Kantarjian HM, Ghorab A, et al.: Prognostic factors and survival outcomes in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in blast phase in the tyrosine kinase inhibitor era: Cohort study of 477 patients. Cancer 123 (22): 4391-4402, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wagner JE, Zahurak M, Piantadosi S, et al.: Bone marrow transplantation of chronic myelogenous leukemia in chronic phase: evaluation of risks and benefits. J Clin Oncol 10 (5): 779-89, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Enright H, Davies SM, DeFor T, et al.: Relapse after non-T-cell-depleted allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for chronic myelogenous leukemia: early transplantation, use of an unrelated donor, and chronic graft-versus-host disease are protective. Blood 88 (2): 714-20, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Goldman JM, Szydlo R, Horowitz MM, et al.: Choice of pretransplant treatment and timing of transplants for chronic myelogenous leukemia in chronic phase. Blood 82 (7): 2235-8, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Clift RA, Appelbaum FR, Thomas ED: Treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia by marrow transplantation. Blood 82 (7): 1954-6, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hansen JA, Gooley TA, Martin PJ, et al.: Bone marrow transplants from unrelated donors for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 338 (14): 962-8, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Relapsed CML

Treatment Options for Relapsed CML

Treatment options for relapsed chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) include:

Relapsed CML is characterized by any evidence of progression of disease from a stable remission. This may include:

- Increasing myeloid or blast cells in the peripheral blood or bone marrow.

- Cytogenetic positivity when previously cytogenetic negative.

- Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) positivity for BCR::ABL1 translocation when previously FISH negative.

Detection of the BCR::ABL1 translocation by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) during prolonged remissions does not constitute relapse on its own. However, exponential drops in quantitative RT-PCR measurements for 3 to 12 months correlates with the degree of cytogenetic response, just as exponential rises may be associated with quantitative RT-PCR measurements that are closely connected with clinical relapse.[1] Overt treatment failure is defined as a loss of hematologic remission or progression to accelerated-phase or blast crisis phase CML. A consistently rising quantitative RT-PCR BCR::ABL1 level suggests relapsed disease.

Targeted therapy with TKIs

In case of treatment failure or suboptimal response, patients should undergo BCR::ABL1 kinase domain mutation analysis to help guide therapy with the newer TKIs or with allogeneic transplant.[2,3]

Variants in the tyrosine kinase domain can confer resistance to imatinib mesylate. Alternative TKIs such as dasatinib, nilotinib, or bosutinib, higher doses of imatinib mesylate, and allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT) have been studied in this setting.[4-16] In particular, the T315I variant marks resistance to imatinib, dasatinib, nilotinib, and bosutinib.

Ponatinib

Ponatinib is an oral TKI that has activity in patients with T315I variants or in patients for whom another TKI failed.[17-19] Multiple phase II studies concluded that the optimal response (≤1% BCR::ABL1) and least toxicity occurred at a 45 mg starting dose, with a decrease to 15 mg upon achieving the response.[20,21][Level of evidence C3] Ponatinib is associated with increased cardiovascular adverse events. Patients with significant cardiovascular disease, hypertension, or diabetes mellitus have been excluded from clinical trials.[20,21]

Evidence (ponatinib):

- Ponatinib has been studied in multiple phase II studies involving 799 patients.[17,21][Level of evidence C3]

- Of the 799 patients with the T315I variant or resistance to two or more prior TKIs, 46% to 68% had an optimal response (≤1% BCR::ABL1) to ponatinib.

- In a retrospective review of 184 patients with recurrent chronic CML and the T315I variant, the following was reported:[18][Level of evidence C3]

- Patients treated with ponatinib had a higher 4-year overall survival (OS) rate than did patients treated with allogeneic SCT (73% vs. 56%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.37; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.16−0.84; P = .017).

- For patients with accelerated-phase CML, survival was equivalent; however, for patients with blast crisis-phase CML, OS was worse for those who received ponatinib (HR, 2.29; 95% CI, 1.08−4.82; P = .030).

- In a retrospective review, patients with a T315I variant and CML that did not respond to ponatinib had a poor prognosis, with a median survival of 16 months. The outcomes for these patients were best after allogeneic SCT, but this could have resulted from selection bias.[22][Level of evidence C3]

- A phase II trial of 282 patients was conducted to determine the lowest efficacious dose of ponatinib, because higher doses are correlated with arterial occlusive events.[20]

- The optimal dose was found to be an initial 45 mg dose given once daily, then lowered to 15 mg upon achievement of a response (≤1% BCR::ABL1).[20]

Asciminib

Asciminib is an allosteric inhibitor of BCR::ABL1 at the ABL1 myristoyl pocket, a site unique from those used by TKIs.

Evidence (asciminib):

- An open-label randomized clinical trial compared asciminib with bosutinib. With a median follow-up of 14.9 months, 233 patients with refractory or resistant disease were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive either asciminib or bosutinib.[23]

- The major molecular response (MMR) rate at week 24 was 25.5% for patients who received asciminib versus 13.2% for patients who received bosutinib. The difference in response (adjusted for major cytogenetic response at baseline) was 12.2% (95% CI, 2.19%–22.30%; P = .029).[23][Level of evidence B3]

- Grade 3 or 4 adverse events were experienced by 50.6% of patients who received asciminib and 60.5% of patients who received bosutinib.

- A phase I trial of asciminib included heavily pretreated patients who experienced resistance or unacceptable side effects after standard TKIs. Patients with a T315I variant and those in whom ponatinib failed were included.[24][Level of evidence C3]

- Of 141 patients, 48% achieved an MMR by 12 months.

- A phase II trial included 31 patients who received asciminib.[25][Level of evidence C3]

- An MMR rate of 41% was reported by 12 months.

- Three of nine patients with disease that failed to respond to previous ponatinib responded to asciminib.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Martinelli G, Iacobucci I, Rosti G, et al.: Prediction of response to imatinib by prospective quantitation of BCR-ABL transcript in late chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia patients. Ann Oncol 17 (3): 495-502, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Soverini S, Hochhaus A, Nicolini FE, et al.: BCR-ABL kinase domain mutation analysis in chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: recommendations from an expert panel on behalf of European LeukemiaNet. Blood 118 (5): 1208-15, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Parker WT, Lawrence RM, Ho M, et al.: Sensitive detection of BCR-ABL1 mutations in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia after imatinib resistance is predictive of outcome during subsequent therapy. J Clin Oncol 29 (32): 4250-9, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jabbour E, Cortes J, Kantarjian HM, et al.: Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia and acute lymphocytic leukemia after Bcr-Abl kinase mutation-related imatinib failure. Blood 108 (4): 1421-3, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- le Coutre PD, Giles FJ, Hochhaus A, et al.: Nilotinib in patients with Ph+ chronic myeloid leukemia in accelerated phase following imatinib resistance or intolerance: 24-month follow-up results. Leukemia 26 (6): 1189-94, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hochhaus A, Baccarani M, Deininger M, et al.: Dasatinib induces durable cytogenetic responses in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in chronic phase with resistance or intolerance to imatinib. Leukemia 22 (6): 1200-6, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Guilhot F, Apperley J, Kim DW, et al.: Dasatinib induces significant hematologic and cytogenetic responses in patients with imatinib-resistant or -intolerant chronic myeloid leukemia in accelerated phase. Blood 109 (10): 4143-50, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kantarjian HM, Giles FJ, Bhalla KN, et al.: Nilotinib is effective in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase after imatinib resistance or intolerance: 24-month follow-up results. Blood 117 (4): 1141-5, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kantarjian H, Cortes J, Kim DW, et al.: Phase 3 study of dasatinib 140 mg once daily versus 70 mg twice daily in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in accelerated phase resistant or intolerant to imatinib: 15-month median follow-up. Blood 113 (25): 6322-9, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jabbour E, Jones D, Kantarjian HM, et al.: Long-term outcome of patients with chronic myeloid leukemia treated with second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors after imatinib failure is predicted by the in vitro sensitivity of BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations. Blood 114 (10): 2037-43, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Apperley JF, Cortes JE, Kim DW, et al.: Dasatinib in the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia in accelerated phase after imatinib failure: the START a trial. J Clin Oncol 27 (21): 3472-9, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hughes T, Saglio G, Branford S, et al.: Impact of baseline BCR-ABL mutations on response to nilotinib in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase. J Clin Oncol 27 (25): 4204-10, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kantarjian H, Pasquini R, Lévy V, et al.: Dasatinib or high-dose imatinib for chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia resistant to imatinib at a dose of 400 to 600 milligrams daily: two-year follow-up of a randomized phase 2 study (START-R). Cancer 115 (18): 4136-47, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Saglio G, Hochhaus A, Goh YT, et al.: Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant or imatinib-intolerant chronic myeloid leukemia in blast phase after 2 years of follow-up in a phase 3 study: efficacy and tolerability of 140 milligrams once daily and 70 milligrams twice daily. Cancer 116 (16): 3852-61, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cortes JE, Kantarjian HM, Brümmendorf TH, et al.: Safety and efficacy of bosutinib (SKI-606) in chronic phase Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia patients with resistance or intolerance to imatinib. Blood 118 (17): 4567-76, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Khoury HJ, Cortes JE, Kantarjian HM, et al.: Bosutinib is active in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia after imatinib and dasatinib and/or nilotinib therapy failure. Blood 119 (15): 3403-12, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cortes JE, Kim DW, Pinilla-Ibarz J, et al.: A phase 2 trial of ponatinib in Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med 369 (19): 1783-96, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Nicolini FE, Basak GW, Kim DW, et al.: Overall survival with ponatinib versus allogeneic stem cell transplantation in Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias with the T315I mutation. Cancer 123 (15): 2875-2880, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Shacham-Abulafia A, Raanani P, Lavie D, et al.: Real-life Experience With Ponatinib in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: A Multicenter Observational Study. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 18 (7): e295-e301, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cortes J, Apperley J, Lomaia E, et al.: Ponatinib dose-ranging study in chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia: a randomized, open-label phase 2 clinical trial. Blood 138 (21): 2042-2050, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kantarjian HM, Jabbour E, Deininger M, et al.: Ponatinib after failure of second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor in resistant chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. Am J Hematol 97 (11): 1419-1426, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Boddu P, Shah AR, Borthakur G, et al.: Life after ponatinib failure: outcomes of chronic and accelerated phase CML patients who discontinued ponatinib in the salvage setting. Leuk Lymphoma 59 (6): 1312-1322, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Réa D, Mauro MJ, Boquimpani C, et al.: A phase 3, open-label, randomized study of asciminib, a STAMP inhibitor, vs bosutinib in CML after 2 or more prior TKIs. Blood 138 (21): 2031-2041, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hughes TP, Mauro MJ, Cortes JE, et al.: Asciminib in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia after ABL Kinase Inhibitor Failure. N Engl J Med 381 (24): 2315-2326, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Garcia-Gutiérrez V, Luna A, Alonso-Dominguez JM, et al.: Safety and efficacy of asciminib treatment in chronic myeloid leukemia patients in real-life clinical practice. Blood Cancer J 11 (2): 16, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

Key References for CML

These references have been identified by members of the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board as significant in the field of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) treatment. This list is provided to inform users of important studies that have helped shape the current understanding of and treatment options for CML. Listed after each reference are the sections within this summary where the reference is cited.

- Hughes TP, Saglio G, Kantarjian HM, et al.: Early molecular response predicts outcomes in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase treated with frontline nilotinib or imatinib. Blood 123 (9): 1353-60, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

Cited in:

- Jabbour E, Kantarjian HM, Saglio G, et al.: Early response with dasatinib or imatinib in chronic myeloid leukemia: 3-year follow-up from a randomized phase 3 trial (DASISION). Blood 123 (4): 494-500, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

Cited in:

- Kantarjian HM, Hochhaus A, Saglio G, et al.: Nilotinib versus imatinib for the treatment of patients with newly diagnosed chronic phase, Philadelphia chromosome-positive, chronic myeloid leukaemia: 24-month minimum follow-up of the phase 3 randomised ENESTnd trial. Lancet Oncol 12 (9): 841-51, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

Cited in:

Latest Updates to This Summary (03/13/2025)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

General Information About Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML)

Updated statistics with estimated new cases and deaths for 2025 (cited American Cancer Society as reference 1).

Treatment of Chronic-Phase CML

Revised text about a prospective study that included 405 patients with newly diagnosed CML. Patients were randomly assigned to receive asciminib or either imatinib mesylate or nilotinib, dasatinib, or bosutinib. A prespecified subgroup analysis compared asciminib with the second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (not including imatinib). At week 48, 66.0% who received asciminib had a major molecular response (MMR), and 57.8% of patients who received second-generation TKIs had an MMR. The 8.2% difference was not statistically significant. In the first year, it appears that the efficacy of asciminib is equivalent to those of second-generation TKIs. Longer follow-up is required to fully assess efficacy and toxicity outcomes.

This summary is written and maintained by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of NCI. The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or NIH. More information about summary policies and the role of the PDQ Editorial Boards in maintaining the PDQ summaries can be found on the About This PDQ Summary and PDQ® Cancer Information for Health Professionals pages.

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board, which is editorially independent of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The summary reflects an independent review of the literature and does not represent a policy statement of NCI or the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewers for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Treatment are:

- Aaron Gerds, MD (Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute)

- Eric J. Seifter, MD (Johns Hopkins University)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's Email Us. Do not contact the individual Board Members with questions or comments about the summaries. Board members will not respond to individual inquiries.

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board uses a formal evidence ranking system in developing its level-of-evidence designations.

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as “NCI’s PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary].”

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/leukemia/hp/cml-treatment-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389354]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in Visuals Online, a collection of over 2,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

Based on the strength of the available evidence, treatment options may be described as either “standard” or “under clinical evaluation.” These classifications should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website’s Email Us.