Ewing Sarcoma and Undifferentiated Small Round Cell Sarcomas of Bone and Soft Tissue Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version

General Information About Ewing Sarcoma and Undifferentiated Small Round Cell Sarcomas of Bone and Soft Tissue

Dramatic improvements in survival have been achieved for children and adolescents with cancer.[1] Between 1975 and 2020, childhood cancer mortality decreased by more than 50%.[1-3] For Ewing sarcoma, the 5-year survival rate has increased from 59% to a range of 80% to 85% for children younger than 15 years and from 20% to 69% for adolescents aged 15 to 19 years.[1,2]

Studies using immunohistochemical markers,[4] cytogenetics,[5,6] molecular genetics, and tissue culture [7] indicate that Ewing sarcoma originates from a primordial bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cell.[8,9] Older terms such as peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor, Askin tumor (Ewing sarcoma of chest wall), and extraosseous Ewing sarcoma (often combined in the term Ewing sarcoma family of tumors) refer to this same tumor.

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of soft tissue and bone was modified in 2020 to introduce a new chapter on undifferentiated small round cell sarcomas of bone and soft tissue. This WHO chapter consists of Ewing sarcoma and three main categories, including round cell sarcomas with EWSR1::non-ETS fusions, CIC-rearranged sarcoma, and sarcomas with BCOR genetic alterations.[10]

Before the widespread availability of genomic testing, Ewing sarcoma was identified by the appearance of small, round, blue cells on light microscopic examination, along with positive staining for CD99 by immunohistochemistry. The identification of the recurring t(11;22) translocation in most Ewing sarcoma tumors led to the discovery that most tumors classified as Ewing sarcoma had a translocation that juxtaposed a portion of the EWSR1 gene to a portion of a gene in the ETS family, resulting in a transforming transcript. Not all undifferentiated small round cell sarcomas of bone and soft tissue have such a translocation. Further research identified additional genetic changes, including tumors with translocations of the CIC gene or the BCOR gene. These groups of tumors occur much less frequently than Ewing sarcoma, and data on these patients are based on smaller sample sizes and less homogeneous treatment; therefore, patient outcomes are harder to quantify with precision. Most of these tumors have been treated with regimens designed for Ewing sarcoma, and the consensus was that they were often included in clinical trials for the treatment of Ewing sarcoma, sometimes referred to as translocation-negative Ewing sarcoma. It is now agreed that these tumors are sufficiently different from Ewing sarcoma and that they should be stratified and analyzed separately from Ewing sarcoma, even if they are treated with similar therapy. In this summary, these tumors are described separately. For more information about these smaller groups of tumors, see the following sections:

Incidence

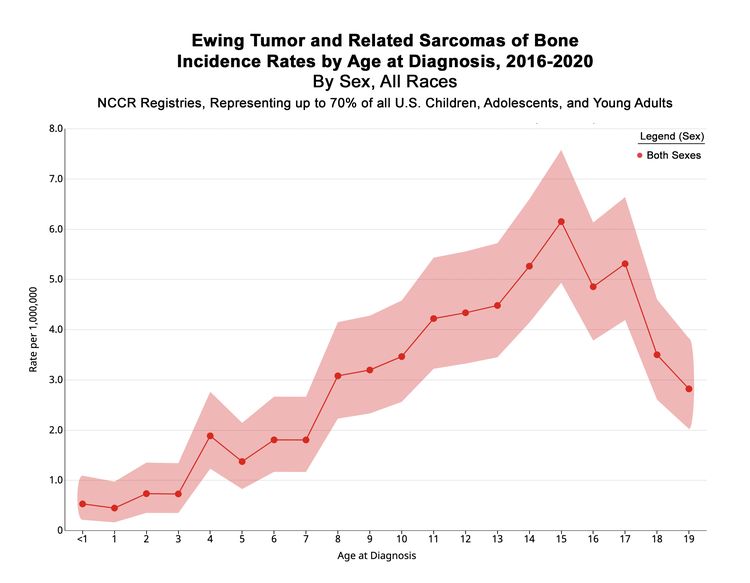

In the United States between 2016 and 2020, the National Childhood Cancer Registry (NCCR) reported an incidence rate of Ewing sarcoma and related sarcomas of bone of 3.0 cases per 1 million in children and adolescents younger than 20 years.[2] This incidence is unchanged from that reported between 1973 and 2004.[11] The incidence rates by age groups in the U.S. pediatric population for Ewing sarcoma and related sarcomas of bone are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. While well-characterized cases of Ewing sarcoma in neonates and infants have been described, the incidence is low in infants and young children and then increases in adolescents.[12,13]

| Age (years) | Rate per 1,000,000 | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| aSource: National Childhood Cancer Registry (NCCR) Explorer.[2] | ||

| <1 | 0.5 | 0.2–1.1 |

| 1–4 | 1 | 0.7–1.3 |

| 5–9 | 2.3 | 1.9–2.6 |

| 10–14 | 4.3 | 3.9–4.9 |

| 15–19 | 4.5 | 4.0–5.0 |

The incidence of Ewing sarcoma in the United States is nine times greater in White people than in Black people, with an intermediate incidence in Asian people.[14,15] The relative paucity of Ewing sarcoma in people of African or Asian descent may be explained, in part, by a specific polymorphism in the EGR2 gene.[16]

Based on data from 1,426 patients entered on European Intergroup Cooperative Ewing Sarcoma Studies, 59% of patients are male and 41% are female.[17] These results match the 58%-to-42% male-to-female distribution in the United States (age <20 years) in the NCCR dataset (3.5 and 2.5 cases per million incidence rate for males and females, respectively).[2]

Genetic Predisposition to Ewing Sarcoma

Conventional understanding of translocation-driven sarcoma such as Ewing sarcoma suggests that these patients do not have a genetic predisposition.[18] A retrospective European-focused and panancestry case-controlled analysis was performed. The purpose of this study was to screen for enrichment of pathogenic germline variants in 141 known cancer predisposition genes in 1,147 pediatric patients diagnosed with sarcomas (226 Ewing sarcomas, 438 osteosarcomas, 180 rhabdomyosarcomas, and 303 other sarcomas), and compared the results to identically processed cancer-free control individuals. A distinct pattern of pathogenic germline variants was seen in Ewing sarcoma compared with other sarcoma types. FANCC was the only gene with an enrichment signal for heterozygous pathogenic variants in the European Ewing sarcoma discovery cohort (three individuals; odds ratio [OR], 12.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.0–43.2; P = .003; false discovery rate, 0.40). This enrichment in FANCC heterozygous pathogenic variants was again observed in the European Ewing sarcoma validation cohort (three individuals; OR, 7.0; 95% CI, 1.7–23.6; P = .014).

Genome-wide association studies have identified susceptibility loci for Ewing sarcoma at 1p36.22, 10q21, and 15q15.[16,19,20] Deep sequencing through the 10q21.3 region identified a polymorphism in the EGR2 gene, which appears to cooperate with and magnify the enhanced activity of the gene product of the EWSR1::FLI1 fusion gene that is seen in most patients with Ewing sarcoma.[16] The polymorphism associated with the increased risk is found at a much higher frequency in White people than in Black or Asian people, possibly contributing to the epidemiology of the relative infrequency of Ewing sarcoma in the latter populations. Three new susceptibility loci have been identified at 6p25.1, 20p11.22, and 20p11.23.[20]

Clinical Presentation

Clinical presentation of Ewing sarcoma varies and depends on the tumor’s size and location.

Primary sites of bone disease are listed in Table 2.[21]

| Primary Site | Incidence Rate |

|---|---|

| Skull | 5% |

| Spine | 7% |

| Rib | 11% |

| Sternum, scapula, and clavicle | 5% |

| Humerus | 7% |

| Radius, ulna, hand | 2% |

| Pelvis | 18% |

| Femur | 11% |

| Tibia, fibula, patella, foot | 14% |

| Soft tissue | 19% |

The time from the first symptom to diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma is often long, with a median interval reported from 2 to 5 months. Longer times are associated with older age and pelvic primary sites. Time from the first symptom to diagnosis has not been associated with metastasis, surgical outcome, or survival.[22]

Approximately 25% of patients with Ewing sarcoma have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis, with lung, bone, and bone marrow being the most common metastatic sites.[11]

A retrospective analysis examined patients treated on two Children's Oncology Group (COG) studies, INT-0154 and AEWS0031 (NCT00006734). This study compared the clinical characteristics of 213 patients with extraskeletal primary Ewing sarcoma with those of 826 patients with primary Ewing sarcoma of bone.[23] Patients with extraskeletal tumors were more likely to be non-White, have axial primary tumors, and have smaller tumors than patients with primary Ewing sarcoma of bone.

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program database was used to compare patients younger than 40 years with Ewing sarcoma who presented with skeletal and extraosseous primary sites (see Table 3).[24] Patients with extraosseous Ewing sarcoma were more likely to be older, female, of non-White race, and have axial primary sites, and they were less likely to have pelvic primary sites than were patients with skeletal Ewing sarcoma.

| Characteristic | Extraosseous Ewing Sarcoma | Skeletal Ewing Sarcoma | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| aAdapted from Applebaum et al.[24] | |||

| Mean age (range), years | 20 (0–39) | 16 (0–39) | <.001 |

| Male | 53% | 63% | <.001 |

| White race | 85% | 93% | <.001 |

| Axial primary sites | 73% | 54% | <.001 |

| Pelvic primary sites | 20% | 27% | .001 |

Diagnostic Evaluation

The following tests and procedures may be used to diagnose or stage Ewing sarcoma:

- Physical examination and history.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of primary tumor site.

- Computed tomography (CT) scan of chest.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) scan.

- Bone scan. Bone scan was traditionally routinely performed on all patients with Ewing sarcoma for staging. However, many investigators believe that the PET scan can replace the bone scan.[25,26]

- Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy.

- X-ray of primary bone sites.

- Complete blood count.

- Blood chemistry studies, such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).

Skip metastasis evaluation is important for primary appendicular bone tumors. Thus, imaging of the entire involved bone is standardly performed. In one retrospective study, skip metastasis was seen in 15.8% of patients. The presence of skip metastasis was associated with an increased risk of distant metastatic disease.[27]

Omission of bone marrow biopsy and aspiration may be considered, when fluorine F 18-fludeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET imaging is used, in patients with otherwise localized disease after initial staging studies. A systematic review of Ewing sarcoma studies was performed to assess the incidence of bone marrow metastasis and the role of 18F-FDG PET imaging to detect bone marrow metastasis.[28] The review reported a pooled incidence of bone marrow metastasis of 4.8% in all patients with newly diagnosed Ewing sarcoma and 17.5% in patients with metastatic disease. Only 1.2% of patients had bone marrow metastasis as their sole metastatic site. Compared with bone marrow biopsy and aspiration, 18F-FDG PET detection of bone marrow metastasis demonstrated pooled 100% sensitivity and 96% specificity, positive predictive value of 75%, and negative predictive value of 100%. For more information about diagnostic biopsy, see the Treatment Option Overview for Ewing Sarcoma section.

Prognostic Factors

The two major types of prognostic factors for patients with Ewing sarcoma are grouped as follows:

Pretreatment factors

- Metastases: The presence or absence of metastatic disease is the single most powerful predictor of outcome. Any metastatic disease defined by standard imaging techniques or bone marrow aspirate/biopsy by morphology is an adverse prognostic factor. Metastases at diagnosis are detected in about 25% of patients.[11]

Patients with metastatic disease confined to the lung have a better prognosis than patients with extrapulmonary metastatic sites.[29-32] The number of pulmonary lesions does not seem to correlate with outcome, but patients with unilateral lung involvement have a better prognosis than patients with bilateral lung involvement.[33]

Patients with metastasis to only bone seem to have a better outcome than patients with metastases to both bone and lung.[34,35]

Based on an analysis from the SEER database, regional lymph node involvement in patients is associated with an inferior overall outcome when compared with patients without regional lymph node involvement.[36]

- Site of tumor: Patients with Ewing sarcoma in the distal extremities have more favorable outcomes. Patients with Ewing sarcoma in the proximal extremities have an intermediate prognosis, followed by patients with central or pelvic sites.[29,31,32,37] However, a trial from the COG showed similar outcomes for patients with pelvic primary tumors compared with other sites.[21]

One study retrospectively analyzed a single-institution's experience with visceral Ewing sarcoma. The study focused on surgical management and compared the outcomes of patients with visceral Ewing sarcoma with those of patients with osseous and soft tissue Ewing sarcoma.[38] There were 156 patients with Ewing sarcoma identified: 117 osseous Ewing sarcomas, 20 soft tissue Ewing sarcomas, and 19 visceral Ewing sarcomas. Visceral Ewing sarcomas arose in the kidneys (n = 5), lungs (n = 5), intestines (n = 2), esophagus (n = 1), liver (n = 1), pancreas (n = 1), adrenal gland (n = 1), vagina (n = 1), brain (n = 1), and spinal cord (n = 1). Visceral Ewing sarcoma was more frequently metastatic at presentation (63.2%; P = .005). However, there was no significant difference in overall survival (OS) or relapse-free survival among the Ewing sarcoma groups, with similar follow-up intervals.

- Extraskeletal versus skeletal primary tumors: The COG performed a retrospective analysis from two large cooperative trials that used similar treatment regimens.[23] They identified 213 patients with extraskeletal primary tumors and 826 patients with skeletal primary tumors. Patients with extraskeletal primary tumors were more likely to have an axial primary site, less likely to have large primary tumors, and had a statistically significant better prognosis than did patients with skeletal primary tumors.

- Tumor size or volume: Most studies have shown that tumor size or volume is an important prognostic factor. Cutoffs of a volume of 100 mL or 200 mL and/or single dimension greater than 8 cm are used to define larger tumors. Larger tumors tend to occur in unfavorable sites.[31,32,39]

- Age: Younger patients generally have a better prognosis than older patients, as noted in the following studies:[13,29,32,37,40-42]

- In North American studies, patients younger than 10 years had a better outcome than those aged 10 to 17 years at diagnosis (relative risk [RR], 1.4). Patients older than 18 years had an inferior outcome (RR, 2.5).[43-45]

- A retrospective review of two consecutive German trials for Ewing sarcoma identified 47 patients older than 40 years.[46] With adequate multimodal therapy, survival was comparable to the survival observed in adolescents treated on the same trials.

- Review of the SEER database from 1973 to 2011 identified 1,957 patients with Ewing sarcoma.[47] Thirty-nine of these patients (2.0%) were younger than 12 months at diagnosis. Infants were less likely to receive radiation therapy and more likely to have soft tissue primary sites. Early death was more common in infants, but the OS did not differ significantly from that of older patients.

- A European retrospective review identified 2,635 patients with Ewing sarcoma of bone.[48] Sites of primary and metastatic tumors differed according to the age groups of young children (0–9 years), early adolescence (10–14 years), late adolescence (15–19 years), young adults (20–24 years), and adults (older than 24 years). Young children had the most striking differences in site of disease, with a lower proportion of pelvic primary and axial tumors. Young children also presented less often with metastatic disease at diagnosis.

- Sex: Females with Ewing sarcoma have a better prognosis than males with Ewing sarcoma.[14,32,37]

- Serum LDH: Increased serum LDH levels before treatment are associated with inferior prognosis. Increased LDH levels are also associated with large primary tumors and metastatic disease.[37]

- Pathological fracture: A single-institution retrospective analysis of 78 patients with Ewing sarcoma suggested that pathological fracture at initial presentation was associated with inferior event-free survival (EFS) and OS.[49][Level of evidence C1] Another study found that pathological fracture at the time of diagnosis did not preclude surgical resection and was not associated with an adverse outcome.[50]

- Previous treatment for cancer: In the SEER database, 58 patients with Ewing sarcoma were diagnosed after treatment for a previous malignancy (2.1% of patients with Ewing sarcoma). These patients were compared with 2,756 patients with Ewing sarcoma as a first cancer over the same period. Patients with Ewing sarcoma as a second malignant neoplasm were older (secondary Ewing sarcoma, mean age of 47.8 years; primary Ewing sarcoma, mean age of 22.5 years), more likely to have a primary tumor in an axial or extraskeletal site, and had a worse prognosis (5-year OS rates of 43.5% for patients with secondary Ewing sarcoma and 64.2% for patients with primary Ewing sarcoma).[51]

-

Chromosomal alterations:

- Complex karyotype (defined as the presence of five or more independent chromosome abnormalities at diagnosis) and modal chromosome numbers lower than 50 appear to have adverse prognostic significance.[52]

- Gain of chromosome 1q and/or deletion of chromosome 16q has been associated with inferior prognosis for patients with Ewing sarcoma in several cohorts.[53-55] These two chromosomal alterations commonly occur together across a range of cancer types, including Ewing sarcoma.[56] Their co-occurrence is likely a result of their derivation from an unbalanced t(1;16) translocation resulting in gain of chromosome 1q together with loss of chromosomal material from 16q.[57,58]

- Detectable Ewing sarcoma cells, fusion transcripts, or circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in peripheral blood: Several techniques to evaluate the presence of Ewing sarcoma in the peripheral blood have been proposed. Flow cytometry for cells that express the CD99 antigen was not sufficiently sensitive to serve as a reliable biomarker.[59,60] Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for the EWSR1::FLI1 translocation was also not considered a reliable biomarker.[61]

A more sensitive technique used patient-specific primers designed after identification of the specific translocation breakpoint in combination with droplet digital PCR to detect the EWSR1 fusion. This technique reported a sensitivity threshold of 0.009% to 0.018%.[62] Levels of circulating cell-free DNA were higher in patients with metastatic disease than in patients with localized disease.

A next-generation sequencing hybrid capture assay and an ultra-low-pass whole-genome sequencing assay were used to detect the EWSR1 fusion in ctDNA in banked plasma from patients with Ewing sarcoma. Among patients with newly diagnosed localized Ewing sarcoma, detectable ctDNA was associated with inferior 3-year EFS rates (48.6% vs. 82.1%; P = .006) and OS rates (79.8% vs. 92.6%; P = .01).[63]

ctDNA was separately assayed by digital-droplet PCR in 102 patients who were treated in the EWING2008 (NCT00987636) trial.[64] Pretreatment ctDNA copy numbers correlated with EFS and OS. A reduction in ctDNA levels below the detection limit was observed in most patients after only two blocks of vincristine, ifosfamide, doxorubicin, and etoposide (VIDE) induction chemotherapy. The persistence of ctDNA after two blocks of VIDE was a strong predictor of poor outcomes.

- Detectable fusion transcripts in morphologically normal marrow: RT-PCR can be used to detect fusion transcripts in bone marrow. In a single retrospective study using patients with normal marrow morphology and no other metastatic site, fusion transcript detection in marrow or peripheral blood was associated with an increased risk of relapse.[60] However, a larger cohort (n = 225) of patients with localized Ewing sarcoma did not show a difference in EFS or OS based on the detection of fusion transcripts in blood or bone marrow.[65]

- Gene alterations: A prospective analysis of TP53 variants and/or CDKN2A deletions was done in patients with Ewing sarcoma enrolled on COG clinical trials. The analysis found no association of these alterations with EFS.[66]

In a study of 299 patients with Ewing sarcoma, 41 patients (14%) had STAG2 variants and 16 patients (5%) had TP53 variants.[55] There was no association with OS for patients with either the STAG2 or TP53 variant alone. However, the nine patients (3%) with tumors that had both STAG2 and TP53 variants had a significantly decreased OS rate (<20% at 4 years).

The COG analyzed STAG2 expression by immunohistochemistry in children with Ewing sarcoma who participated in frontline treatment trials.[67] STAG2 was lost in 29 of 108 patients with localized disease and in 6 of 27 patients with metastatic disease. Among patients who had immunohistochemistry and sequencing performed, no cases (0 of 17) with STAG2 expression had STAG2 variants, and 2 of 7 cases with STAG2 loss had STAG2 variants. Among patients with localized disease, the 5-year EFS rate was 54% (95% CI, 34%–70%) for those with STAG2 loss, compared with 75% (95% CI, 63%–84%) for those with STAG2 expression (P = .0034).

The following are not considered to be adverse prognostic factors for Ewing sarcoma:

- Histopathology: The degree of neural differentiation is not a prognostic factor in Ewing sarcoma.[68,69]

- Fusion subtype: The EWSR1::ETS translocation associated with Ewing sarcoma can occur at several potential breakpoints in each of the genes that join to form the novel segment of DNA. Once thought to be significant,[70] two large series have shown that the EWSR1::ETS translocation breakpoint site is not an adverse prognostic factor.[71,72]

Response to initial therapy factors

Multiple studies have shown that patients with minimal or no residual viable tumor after presurgical chemotherapy have a significantly better EFS than do patients with larger amounts of viable tumor.[21,73-76]; [77][Level of evidence C2] In particular, patients with localized disease who have no viable tumor seen at the time of local-control surgery appear to have markedly favorable outcomes.[21]; [77][Level of evidence C2] Female sex and younger age predict a good histological response to preoperative therapy.[78] For patients who receive preinduction- and postinduction-chemotherapy PET scans, decreased PET uptake after chemotherapy correlated with good histological response and better outcome.[79-81]

Patients with poor response to presurgical chemotherapy have an increased risk of local recurrence.[82]

A retrospective analysis of risk factors for recurrence was performed in patients who received initial chemotherapy and underwent surgical resection of the primary tumor.[83][Level of evidence C1] Among 982 patients with a median follow-up of 7.6 years, the following was reported:

- Adverse risk factors for local recurrence were pelvic primary tumors (hazard ratio [HR], 2.04; 95% CI, 1.10–3.80) and marginal/intralesional resection (HR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.25–4.16). The addition of radiation therapy was associated with improved outcome (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.28–0.95).

- Adverse risk factors for developing new pulmonary metastasis were less than 90% necrosis (HR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.13–4.00) and previous pulmonary metastasis (HR, 4.90; 95% CI, 2.28–8.52).

- Adverse risk factors for death included pulmonary metastasis (HR, 8.08; 95% CI, 4.01–16.29), bone or other metastasis (HR, 10.23; 95% CI, 4.90–21.36), and less than 90% necrosis (HR, 6.35; 95% CI, 3.18–12.69).

- Early local recurrence (0–24 months) negatively influenced survival (HR, 3.79; 95% CI, 1.34–10.76).

In a retrospective cohort of 148 patients with pulmonary metastatic Ewing sarcoma, 41.2% had radiographic resolution of lung nodules after initial induction chemotherapy.[84] These patients had superior OS compared with patients who had residual nodules at end-induction (71.2% vs. 50.2% at 5 years). Particularly favorable outcomes were seen in the patients who had early clearance of lung nodules and received consolidative whole-lung radiation therapy (5-year OS rate, 85.2%).

References

- Smith MA, Altekruse SF, Adamson PC, et al.: Declining childhood and adolescent cancer mortality. Cancer 120 (16): 2497-506, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- National Cancer Institute: NCCR*Explorer: An interactive website for NCCR cancer statistics. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Available online. Last accessed February 25, 2025.

- Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute: SEER*Explorer: An interactive website for SEER cancer statistics. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Available online. Last accessed December 30, 2024.

- Olsen SH, Thomas DG, Lucas DR: Cluster analysis of immunohistochemical profiles in synovial sarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, and Ewing sarcoma. Mod Pathol 19 (5): 659-68, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Delattre O, Zucman J, Melot T, et al.: The Ewing family of tumors--a subgroup of small-round-cell tumors defined by specific chimeric transcripts. N Engl J Med 331 (5): 294-9, 1994. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dagher R, Pham TA, Sorbara L, et al.: Molecular confirmation of Ewing sarcoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 23 (4): 221-4, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Llombart-Bosch A, Carda C, Peydro-Olaya A, et al.: Soft tissue Ewing's sarcoma. Characterization in established cultures and xenografts with evidence of a neuroectodermic phenotype. Cancer 66 (12): 2589-601, 1990. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Suvà ML, Riggi N, Stehle JC, et al.: Identification of cancer stem cells in Ewing's sarcoma. Cancer Res 69 (5): 1776-81, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tirode F, Laud-Duval K, Prieur A, et al.: Mesenchymal stem cell features of Ewing tumors. Cancer Cell 11 (5): 421-9, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Choi JH, Ro JY: The 2020 WHO Classification of Tumors of Soft Tissue: Selected Changes and New Entities. Adv Anat Pathol 28 (1): 44-58, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Esiashvili N, Goodman M, Marcus RB: Changes in incidence and survival of Ewing sarcoma patients over the past 3 decades: Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results data. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 30 (6): 425-30, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kim SY, Tsokos M, Helman LJ: Dilemmas associated with congenital ewing sarcoma family tumors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 30 (1): 4-7, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- van den Berg H, Dirksen U, Ranft A, et al.: Ewing tumors in infants. Pediatr Blood Cancer 50 (4): 761-4, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jawad MU, Cheung MC, Min ES, et al.: Ewing sarcoma demonstrates racial disparities in incidence-related and sex-related differences in outcome: an analysis of 1631 cases from the SEER database, 1973-2005. Cancer 115 (15): 3526-36, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Beck R, Monument MJ, Watkins WS, et al.: EWS/FLI-responsive GGAA microsatellites exhibit polymorphic differences between European and African populations. Cancer Genet 205 (6): 304-12, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Grünewald TG, Bernard V, Gilardi-Hebenstreit P, et al.: Chimeric EWSR1-FLI1 regulates the Ewing sarcoma susceptibility gene EGR2 via a GGAA microsatellite. Nat Genet 47 (9): 1073-8, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Paulussen M, Craft AW, Lewis I, et al.: Results of the EICESS-92 Study: two randomized trials of Ewing's sarcoma treatment--cyclophosphamide compared with ifosfamide in standard-risk patients and assessment of benefit of etoposide added to standard treatment in high-risk patients. J Clin Oncol 26 (27): 4385-93, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gillani R, Camp SY, Han S, et al.: Germline predisposition to pediatric Ewing sarcoma is characterized by inherited pathogenic variants in DNA damage repair genes. Am J Hum Genet 109 (6): 1026-1037, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Postel-Vinay S, Véron AS, Tirode F, et al.: Common variants near TARDBP and EGR2 are associated with susceptibility to Ewing sarcoma. Nat Genet 44 (3): 323-7, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Machiela MJ, Grünewald TGP, Surdez D, et al.: Genome-wide association study identifies multiple new loci associated with Ewing sarcoma susceptibility. Nat Commun 9 (1): 3184, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Leavey PJ, Laack NN, Krailo MD, et al.: Phase III Trial Adding Vincristine-Topotecan-Cyclophosphamide to the Initial Treatment of Patients With Nonmetastatic Ewing Sarcoma: A Children's Oncology Group Report. J Clin Oncol 39 (36): 4029-4038, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Brasme JF, Chalumeau M, Oberlin O, et al.: Time to diagnosis of Ewing tumors in children and adolescents is not associated with metastasis or survival: a prospective multicenter study of 436 patients. J Clin Oncol 32 (18): 1935-40, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cash T, McIlvaine E, Krailo MD, et al.: Comparison of clinical features and outcomes in patients with extraskeletal versus skeletal localized Ewing sarcoma: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 63 (10): 1771-9, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Applebaum MA, Worch J, Matthay KK, et al.: Clinical features and outcomes in patients with extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma. Cancer 117 (13): 3027-32, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tal AL, Doshi H, Parkar F, et al.: The Utility of 18FDG PET/CT Versus Bone Scan for Identification of Bone Metastases in a Pediatric Sarcoma Population and a Review of the Literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 43 (2): 52-58, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Costelloe CM, Chuang HH, Daw NC: PET/CT of Osteosarcoma and Ewing Sarcoma. Semin Roentgenol 52 (4): 255-268, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Saifuddin A, Michelagnoli M, Pressney I: Skip metastases in appendicular Ewing sarcoma: relationship to distant metastases at diagnosis, chemotherapy response and overall survival. Skeletal Radiol 52 (3): 585-591, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Campbell KM, Shulman DS, Grier HE, et al.: Role of bone marrow biopsy for staging new patients with Ewing sarcoma: A systematic review. Pediatr Blood Cancer 68 (2): e28807, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cotterill SJ, Ahrens S, Paulussen M, et al.: Prognostic factors in Ewing's tumor of bone: analysis of 975 patients from the European Intergroup Cooperative Ewing's Sarcoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol 18 (17): 3108-14, 2000. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Miser JS, Krailo MD, Tarbell NJ, et al.: Treatment of metastatic Ewing's sarcoma or primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone: evaluation of combination ifosfamide and etoposide--a Children's Cancer Group and Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 22 (14): 2873-6, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rodríguez-Galindo C, Liu T, Krasin MJ, et al.: Analysis of prognostic factors in ewing sarcoma family of tumors: review of St. Jude Children's Research Hospital studies. Cancer 110 (2): 375-84, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Karski EE, McIlvaine E, Segal MR, et al.: Identification of Discrete Prognostic Groups in Ewing Sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 63 (1): 47-53, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Paulussen M, Ahrens S, Craft AW, et al.: Ewing's tumors with primary lung metastases: survival analysis of 114 (European Intergroup) Cooperative Ewing's Sarcoma Studies patients. J Clin Oncol 16 (9): 3044-52, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Paulussen M, Ahrens S, Burdach S, et al.: Primary metastatic (stage IV) Ewing tumor: survival analysis of 171 patients from the EICESS studies. European Intergroup Cooperative Ewing Sarcoma Studies. Ann Oncol 9 (3): 275-81, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ladenstein R, Pötschger U, Le Deley MC, et al.: Primary disseminated multifocal Ewing sarcoma: results of the Euro-EWING 99 trial. J Clin Oncol 28 (20): 3284-91, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Applebaum MA, Goldsby R, Neuhaus J, et al.: Clinical features and outcomes in patients with Ewing sarcoma and regional lymph node involvement. Pediatr Blood Cancer 59 (4): 617-20, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bacci G, Longhi A, Ferrari S, et al.: Prognostic factors in non-metastatic Ewing's sarcoma tumor of bone: an analysis of 579 patients treated at a single institution with adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy between 1972 and 1998. Acta Oncol 45 (4): 469-75, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wallace MW, Niec JA, Ghani MOA, et al.: Distribution and Surgical Management of Visceral Ewing Sarcoma Among Children and Adolescents. J Pediatr Surg 58 (9): 1727-1735, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ahrens S, Hoffmann C, Jabar S, et al.: Evaluation of prognostic factors in a tumor volume-adapted treatment strategy for localized Ewing sarcoma of bone: the CESS 86 experience. Cooperative Ewing Sarcoma Study. Med Pediatr Oncol 32 (3): 186-95, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- De Ioris MA, Prete A, Cozza R, et al.: Ewing sarcoma of the bone in children under 6 years of age. PLoS One 8 (1): e53223, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Huh WW, Daw NC, Herzog CE, et al.: Ewing sarcoma family of tumors in children younger than 10 years of age. Pediatr Blood Cancer 64 (4): , 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ahmed SK, Randall RL, DuBois SG, et al.: Identification of Patients With Localized Ewing Sarcoma at Higher Risk for Local Failure: A Report From the Children's Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 99 (5): 1286-1294, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Grier HE, Krailo MD, Tarbell NJ, et al.: Addition of ifosfamide and etoposide to standard chemotherapy for Ewing's sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone. N Engl J Med 348 (8): 694-701, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Granowetter L, Womer R, Devidas M, et al.: Dose-intensified compared with standard chemotherapy for nonmetastatic Ewing sarcoma family of tumors: a Children's Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 27 (15): 2536-41, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Womer RB, West DC, Krailo MD, et al.: Randomized controlled trial of interval-compressed chemotherapy for the treatment of localized Ewing sarcoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 30 (33): 4148-54, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Pieper S, Ranft A, Braun-Munzinger G, et al.: Ewing's tumors over the age of 40: a retrospective analysis of 47 patients treated according to the International Clinical Trials EICESS 92 and EURO-E.W.I.N.G. 99. Onkologie 31 (12): 657-63, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wong T, Goldsby RE, Wustrack R, et al.: Clinical features and outcomes of infants with Ewing sarcoma under 12 months of age. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62 (11): 1947-51, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Worch J, Ranft A, DuBois SG, et al.: Age dependency of primary tumor sites and metastases in patients with Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 65 (9): e27251, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schlegel M, Zeumer M, Prodinger PM, et al.: Impact of Pathological Fractures on the Prognosis of Primary Malignant Bone Sarcoma in Children and Adults: A Single-Center Retrospective Study of 205 Patients. Oncology 94 (6): 354-362, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bramer JA, Abudu AA, Grimer RJ, et al.: Do pathological fractures influence survival and local recurrence rate in bony sarcomas? Eur J Cancer 43 (13): 1944-51, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Applebaum MA, Goldsby R, Neuhaus J, et al.: Clinical features and outcomes in patients with secondary Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60 (4): 611-5, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Roberts P, Burchill SA, Brownhill S, et al.: Ploidy and karyotype complexity are powerful prognostic indicators in the Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors: a study by the United Kingdom Cancer Cytogenetics and the Children's Cancer and Leukaemia Group. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 47 (3): 207-20, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hattinger CM, Pötschger U, Tarkkanen M, et al.: Prognostic impact of chromosomal aberrations in Ewing tumours. Br J Cancer 86 (11): 1763-9, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mackintosh C, Ordóñez JL, García-Domínguez DJ, et al.: 1q gain and CDT2 overexpression underlie an aggressive and highly proliferative form of Ewing sarcoma. Oncogene 31 (10): 1287-98, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tirode F, Surdez D, Ma X, et al.: Genomic landscape of Ewing sarcoma defines an aggressive subtype with co-association of STAG2 and TP53 mutations. Cancer Discov 4 (11): 1342-53, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mrózek K, Bloomfield CD: Der(16)t(1;16) is a secondary chromosome aberration in at least eighteen different types of human cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 23 (1): 78-80, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mugneret F, Lizard S, Aurias A, et al.: Chromosomes in Ewing's sarcoma. II. Nonrandom additional changes, trisomy 8 and der(16)t(1;16). Cancer Genet Cytogenet 32 (2): 239-45, 1988. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hattinger CM, Rumpler S, Ambros IM, et al.: Demonstration of the translocation der(16)t(1;16)(q12;q11.2) in interphase nuclei of Ewing tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 17 (3): 141-50, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dubois SG, Epling CL, Teague J, et al.: Flow cytometric detection of Ewing sarcoma cells in peripheral blood and bone marrow. Pediatr Blood Cancer 54 (1): 13-8, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schleiermacher G, Peter M, Oberlin O, et al.: Increased risk of systemic relapses associated with bone marrow micrometastasis and circulating tumor cells in localized ewing tumor. J Clin Oncol 21 (1): 85-91, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Zoubek A, Ladenstein R, Windhager R, et al.: Predictive potential of testing for bone marrow involvement in Ewing tumor patients by RT-PCR: a preliminary evaluation. Int J Cancer 79 (1): 56-60, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Shukla NN, Patel JA, Magnan H, et al.: Plasma DNA-based molecular diagnosis, prognostication, and monitoring of patients with EWSR1 fusion-positive sarcomas. JCO Precis Oncol 2017: , 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Shulman DS, Klega K, Imamovic-Tuco A, et al.: Detection of circulating tumour DNA is associated with inferior outcomes in Ewing sarcoma and osteosarcoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Br J Cancer 119 (5): 615-621, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Krumbholz M, Eiblwieser J, Ranft A, et al.: Quantification of Translocation-Specific ctDNA Provides an Integrating Parameter for Early Assessment of Treatment Response and Risk Stratification in Ewing Sarcoma. Clin Cancer Res 27 (21): 5922-5930, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Vo KT, Edwards JV, Epling CL, et al.: Impact of Two Measures of Micrometastatic Disease on Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Ewing Sarcoma: A Report from the Children's Oncology Group. Clin Cancer Res 22 (14): 3643-50, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lerman DM, Monument MJ, McIlvaine E, et al.: Tumoral TP53 and/or CDKN2A alterations are not reliable prognostic biomarkers in patients with localized Ewing sarcoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62 (5): 759-65, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Shulman DS, Chen S, Hall D, et al.: Adverse prognostic impact of the loss of STAG2 protein expression in patients with newly diagnosed localised Ewing sarcoma: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Br J Cancer 127 (12): 2220-2226, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Parham DM, Hijazi Y, Steinberg SM, et al.: Neuroectodermal differentiation in Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors does not predict tumor behavior. Hum Pathol 30 (8): 911-8, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Luksch R, Sampietro G, Collini P, et al.: Prognostic value of clinicopathologic characteristics including neuroectodermal differentiation in osseous Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors in children. Tumori 85 (2): 101-7, 1999 Mar-Apr. [PUBMED Abstract]

- de Alava E, Kawai A, Healey JH, et al.: EWS-FLI1 fusion transcript structure is an independent determinant of prognosis in Ewing's sarcoma. J Clin Oncol 16 (4): 1248-55, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- van Doorninck JA, Ji L, Schaub B, et al.: Current treatment protocols have eliminated the prognostic advantage of type 1 fusions in Ewing sarcoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 28 (12): 1989-94, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Le Deley MC, Delattre O, Schaefer KL, et al.: Impact of EWS-ETS fusion type on disease progression in Ewing's sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor: prospective results from the cooperative Euro-E.W.I.N.G. 99 trial. J Clin Oncol 28 (12): 1982-8, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Paulussen M, Ahrens S, Dunst J, et al.: Localized Ewing tumor of bone: final results of the cooperative Ewing's Sarcoma Study CESS 86. J Clin Oncol 19 (6): 1818-29, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rosito P, Mancini AF, Rondelli R, et al.: Italian Cooperative Study for the treatment of children and young adults with localized Ewing sarcoma of bone: a preliminary report of 6 years of experience. Cancer 86 (3): 421-8, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wunder JS, Paulian G, Huvos AG, et al.: The histological response to chemotherapy as a predictor of the oncological outcome of operative treatment of Ewing sarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg Am 80 (7): 1020-33, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Oberlin O, Deley MC, Bui BN, et al.: Prognostic factors in localized Ewing's tumours and peripheral neuroectodermal tumours: the third study of the French Society of Paediatric Oncology (EW88 study). Br J Cancer 85 (11): 1646-54, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lozano-Calderón SA, Albergo JI, Groot OQ, et al.: Complete tumor necrosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy defines good responders in patients with Ewing sarcoma. Cancer 129 (1): 60-70, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ferrari S, Bertoni F, Palmerini E, et al.: Predictive factors of histologic response to primary chemotherapy in patients with Ewing sarcoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 29 (6): 364-8, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hawkins DS, Schuetze SM, Butrynski JE, et al.: [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography predicts outcome for Ewing sarcoma family of tumors. J Clin Oncol 23 (34): 8828-34, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Denecke T, Hundsdörfer P, Misch D, et al.: Assessment of histological response of paediatric bone sarcomas using FDG PET in comparison to morphological volume measurement and standardized MRI parameters. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 37 (10): 1842-53, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Palmerini E, Colangeli M, Nanni C, et al.: The role of FDG PET/CT in patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy for localized bone sarcomas. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 44 (2): 215-223, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lin PP, Jaffe N, Herzog CE, et al.: Chemotherapy response is an important predictor of local recurrence in Ewing sarcoma. Cancer 109 (3): 603-11, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bosma SE, Rueten-Budde AJ, Lancia C, et al.: Individual risk evaluation for local recurrence and distant metastasis in Ewing sarcoma: A multistate model: A multistate model for Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 66 (11): e27943, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Reiter AJ, Huang L, Craig BT, et al.: Survival outcomes in pediatric patients with metastatic Ewing sarcoma who achieve a rapid complete response of pulmonary metastases. Pediatr Blood Cancer 71 (7): e31026, 2024. [PUBMED Abstract]

Cellular Classification of Ewing Sarcoma

Ewing sarcoma belongs to the group of neoplasms commonly referred to as small round blue cell tumors of childhood. The individual cells of Ewing sarcoma contain round-to-oval nuclei, with fine dispersed chromatin without nucleoli. Occasionally, cells with smaller, more hyperchromatic, and probably degenerative nuclei are present, giving a light cell/dark cell pattern. The cytoplasm varies in amount, but in the classic case, it is clear and contains glycogen, which can be highlighted with a periodic acid-Schiff stain. The tumor cells are tightly packed and grow in a diffuse pattern without evidence of structural organization. Tumors with the requisite translocation that show neuronal differentiation are not considered a separate entity, but rather, part of a continuum of differentiation.

CD99 is a surface membrane protein that is expressed in most cases of Ewing sarcoma and is useful in diagnosing these tumors when the results are interpreted in the context of clinical and pathological parameters.[1] CD99 positivity is not unique to Ewing sarcoma, and positivity by immunochemistry is found in several other tumors, including synovial sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors. NKX2.2 is a nuclear antigen that is also commonly assessed by immunohistochemistry to support a diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma, although it is also not 100% specific for this diagnosis.[2]

For more information about the cellular classification of other undifferentiated small round cell sarcomas, see the Undifferentiated Small Round Cell (Ewing-Like) Sarcomas section.

References

- Parham DM, Hijazi Y, Steinberg SM, et al.: Neuroectodermal differentiation in Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors does not predict tumor behavior. Hum Pathol 30 (8): 911-8, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Yoshida A, Sekine S, Tsuta K, et al.: NKX2.2 is a useful immunohistochemical marker for Ewing sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 36 (7): 993-9, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

Genomics of Ewing Sarcoma

Molecular Features of Ewing Sarcoma

The World Health Organization identifies the presence of a gene fusion involving EWSR1 or FUS and a gene in the ETS family as a defining element of Ewing sarcoma.[1] The EWSR1 gene located on chromosome 22 band q12 is a member of the FET family (FUS, EWSR1, TAF15) of RNA-binding proteins.[2] Characteristically, the amino terminus of the EWSR1 gene is juxtaposed with the carboxy terminus of a gene from the ETS family of DNA-binding transcription factors (see Table 4). The FLI1 gene located on chromosome 11 band q24 is a member of the ETS family and is the ETS family fusion partner for EWSR1 in 85% to 90% of pediatric cases of Ewing sarcoma.[3-5] Other ETS family members that may combine with the EWSR1 gene are ERG, ETV1, ETV4, and FEV.[6] Rarely, FUS, another FET family member, can substitute for EWSR1.[7] Finally, there are a few rare cases in which EWSR1 has translocated with partners that are not members of the ETS family of oncogenes. These tumors are thought to be distinct from Ewing sarcoma and are discussed separately. For more information, see the Undifferentiated Small Round Cell (Ewing-Like) Sarcomas section.

The EWSR1::FLI1 translocation associated with Ewing sarcoma can occur at several potential breakpoints in each of the genes that join to form the novel segment of DNA. Once thought to be significant,[8] two large series have shown that the EWSR1::FLI1 translocation breakpoint site is not an adverse prognostic factor.[9,10]

Besides the consistent aberrations involving the EWSR1 gene, secondary numerical and structural chromosomal aberrations are observed in most cases of Ewing sarcoma. Chromosome gains are more common than chromosome losses, and structural chromosome imbalances are also observed.[11] Two of the more common chromosome aberrations are those involving chromosome 8 or chromosomes 1 and 16.[11]

- Gain of whole chromosome 8 (trisomy 8). Trisomy 8 is the most frequent chromosomal alteration in Ewing sarcoma, occurring in nearly 50% of tumors.[3,4] Gain of chromosome 8 does not appear to have prognostic significance.[3,12]

- Gain of chromosome 1q and loss of chromosome 16q. These occur in approximately 20% of patients and often occur together. Gain of chromosome 1q and/or deletion of chromosome 16q has been associated with inferior prognosis for patients with Ewing sarcoma in several cohorts.[3,13,14] These two chromosomal alterations commonly occur together across a range of cancer types, including Ewing sarcoma.[15] Their co-occurrence is likely a result of their derivation from an unbalanced t(1;16) translocation resulting in gain of chromosome 1q together with loss of chromosomal material from 16q.[12,16]

The genomic landscape of Ewing sarcoma is characterized by a relatively silent genome, with a paucity of variants in pathways that might be amenable to treatment with novel targeted therapies.[3-5] Recurring genomic alterations are described below. For some of these genomic alterations, claims of prognostic significance have been made. However, these claims need to be viewed cautiously because of the relatively small size of most studies, the low frequency of many of the genomic alterations, the variable use of tumor tissue from diagnosis versus relapse specimens, and the need to consider clinical prognostic factors such as tumor size and the presence of metastatic disease.

- STAG2 variants. Variants in STAG2, a member of the cohesin complex, occur in about 15% to 20% of the cases.[3-5] These variants lead to loss of STAG2 expression and function in tumor cells.[5] Loss of STAG2 expression (detected by immunohistochemistry [IHC]) has been observed in tumors in which a STAG2 variant cannot be detected. In one report, loss of STAG2 expression by IHC was associated with inferior prognosis.[17]

- CDKN2A deletions. CDKN2A deletions have been noted in 12% to 22% of cases.[3-5]

- TP53 variants. TP53 variants were identified in about 6% to 7% of Ewing sarcoma cases reported by pediatric research teams.[3-5] Higher rates of TP53 variants (up to 19%) have been described in cohorts from single institutions that contain higher proportions of adult patients.[18,19] The coexistence of STAG2 and TP53 variants has been associated with a poor clinical outcome in one retrospective report.

- ERF alterations. Genomic alterations in ERF leading to loss of function (frameshift, missense, and deep deletion) were reported in 7% of Ewing sarcoma tumors.[18] A second report observed ERF alterations at a rate of 3% in another Ewing sarcoma cohort.[4]

- Other genes with recurring genomic alterations in Ewing sarcoma. Recurring genomic alterations present in fewer than 5% of Ewing sarcoma patients were reported: EZH2,[3,19] BCOR,[3] SMARCA4,[19] CREBBP,[19] TERT, and FGFR1.[18]

Ewing sarcoma translocations can all be found with standard cytogenetic analysis. A fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) rapid analysis looking for a break apart of the EWSR1 gene is now frequently done to confirm the diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma molecularly.[20] This test result must be considered with caution, however. Ewing sarcomas that harbor FUS translocations will have negative tests because the EWSR1 gene is not translocated in those cases. In addition, other small round tumors also contain translocations of different ETS family members with EWSR1, such as desmoplastic small round cell tumor, clear cell sarcoma, extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma, and myxoid liposarcoma, all of which may be positive with a EWSR1 FISH break-apart probe. A detailed analysis of 85 patients with small round blue cell tumors that were negative for EWSR1 rearrangement by FISH (with an EWSR1 break-apart probe) identified eight patients with FUS rearrangements.[21] Four patients who had EWSR1::ERG fusions were not detected by FISH with an EWSR1 break-apart probe. The authors do not recommend relying solely on EWSR1 break-apart probes for analyzing small round blue cell tumors with strong immunohistochemical positivity for CD99. Next-generation sequencing assays, including dedicated fusion panels, are now commonly used in the evaluation of these tumors.

| FET Family Partner | Fusion With ETS-Like Oncogene Partner | Translocation | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| aThese partners are not members of the ETS family of oncogenes; therefore, these tumors are not classified as Ewing sarcoma. | |||

| EWSR1 | EWSR1::FLI1 | t(11;22)(q24;q12) | Most common; approximately 85% to 90% of cases |

| EWSR1::ERG | t(21;22)(q22;q12) | Second most common; approximately 10% of cases | |

| EWSR1::ETV1 | t(7;22)(p22;q12) | Rare | |

| EWSR1::ETV4 | t(17;22)(q12;q12) | Rare | |

| EWSR1::FEV | t(2;22)(q35;q12) | Rare | |

| EWSR1::NFATC2a | t(20;22)(q13;q12) | Rare | |

| EWSR1::POU5F1a | t(6;22)(p21;q12) | ||

| EWSR1::SMARCA5a | t(4;22)(q31;q12) | Rare | |

| EWSR1::PATZ1a | t(6;22)(p21;q12) | ||

| EWSR1::SP3a | t(2;22)(q31;q12) | Rare | |

| FUS | FUS::ERG | t(16;21)(p11;q22) | Rare |

| FUS::FEV | t(2;16)(q35;p11) | Rare | |

References

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board: WHO Classification of Tumours. Volume 3: Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours. 5th ed., IARC Press, 2020.

- Schwartz JC, Cech TR, Parker RR: Biochemical Properties and Biological Functions of FET Proteins. Annu Rev Biochem 84: 355-79, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tirode F, Surdez D, Ma X, et al.: Genomic landscape of Ewing sarcoma defines an aggressive subtype with co-association of STAG2 and TP53 mutations. Cancer Discov 4 (11): 1342-53, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Crompton BD, Stewart C, Taylor-Weiner A, et al.: The genomic landscape of pediatric Ewing sarcoma. Cancer Discov 4 (11): 1326-41, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Brohl AS, Solomon DA, Chang W, et al.: The genomic landscape of the Ewing Sarcoma family of tumors reveals recurrent STAG2 mutation. PLoS Genet 10 (7): e1004475, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hattinger CM, Rumpler S, Strehl S, et al.: Prognostic impact of deletions at 1p36 and numerical aberrations in Ewing tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 24 (3): 243-54, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sankar S, Lessnick SL: Promiscuous partnerships in Ewing's sarcoma. Cancer Genet 204 (7): 351-65, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- de Alava E, Kawai A, Healey JH, et al.: EWS-FLI1 fusion transcript structure is an independent determinant of prognosis in Ewing's sarcoma. J Clin Oncol 16 (4): 1248-55, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- van Doorninck JA, Ji L, Schaub B, et al.: Current treatment protocols have eliminated the prognostic advantage of type 1 fusions in Ewing sarcoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 28 (12): 1989-94, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Le Deley MC, Delattre O, Schaefer KL, et al.: Impact of EWS-ETS fusion type on disease progression in Ewing's sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor: prospective results from the cooperative Euro-E.W.I.N.G. 99 trial. J Clin Oncol 28 (12): 1982-8, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Roberts P, Burchill SA, Brownhill S, et al.: Ploidy and karyotype complexity are powerful prognostic indicators in the Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors: a study by the United Kingdom Cancer Cytogenetics and the Children's Cancer and Leukaemia Group. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 47 (3): 207-20, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hattinger CM, Rumpler S, Ambros IM, et al.: Demonstration of the translocation der(16)t(1;16)(q12;q11.2) in interphase nuclei of Ewing tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 17 (3): 141-50, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hattinger CM, Pötschger U, Tarkkanen M, et al.: Prognostic impact of chromosomal aberrations in Ewing tumours. Br J Cancer 86 (11): 1763-9, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mackintosh C, Ordóñez JL, García-Domínguez DJ, et al.: 1q gain and CDT2 overexpression underlie an aggressive and highly proliferative form of Ewing sarcoma. Oncogene 31 (10): 1287-98, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mrózek K, Bloomfield CD: Der(16)t(1;16) is a secondary chromosome aberration in at least eighteen different types of human cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 23 (1): 78-80, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mugneret F, Lizard S, Aurias A, et al.: Chromosomes in Ewing's sarcoma. II. Nonrandom additional changes, trisomy 8 and der(16)t(1;16). Cancer Genet Cytogenet 32 (2): 239-45, 1988. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Shulman DS, Chen S, Hall D, et al.: Adverse prognostic impact of the loss of STAG2 protein expression in patients with newly diagnosed localised Ewing sarcoma: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Br J Cancer 127 (12): 2220-2226, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ogura K, Elkrief A, Bowman AS, et al.: Prospective Clinical Genomic Profiling of Ewing Sarcoma: ERF and FGFR1 Mutations as Recurrent Secondary Alterations of Potential Biologic and Therapeutic Relevance. JCO Precis Oncol 6: e2200048, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rock A, Uche A, Yoon J, et al.: Bioinformatic Analysis of Recurrent Genomic Alterations and Corresponding Pathway Alterations in Ewing Sarcoma. J Pers Med 13 (10): , 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Monforte-Muñoz H, Lopez-Terrada D, Affendie H, et al.: Documentation of EWS gene rearrangements by fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) in frozen sections of Ewing's sarcoma-peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor. Am J Surg Pathol 23 (3): 309-15, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Chen S, Deniz K, Sung YS, et al.: Ewing sarcoma with ERG gene rearrangements: A molecular study focusing on the prevalence of FUS-ERG and common pitfalls in detecting EWSR1-ERG fusions by FISH. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 55 (4): 340-9, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

Stage Information for Ewing Sarcoma

Pretreatment staging studies for Ewing sarcoma may include the following:

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the primary site.

- Computed tomography (CT) scan of the primary site and chest.

- Positron emission tomography using fluorine F 18-fludeoxyglucose (18F-FDG PET) or 18F-FDG PET-CT.

- Bone scan has traditionally been part of the staging evaluation for Ewing sarcoma. However, many investigators believe that PET scan can replace bone scan.[1,2]

- Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy.

For patients with confirmed Ewing sarcoma, pretreatment staging studies include MRI and/or CT scan, depending on the primary site. Despite the fact that CT and MRI are both equivalent in terms of staging, use of both imaging modalities may help radiation therapy planning.[3] Whole-body MRI may provide additional information that could potentially alter therapy planning.[4] Additional pretreatment staging studies include bone scan and CT scan of the chest. In certain studies, determination of pretreatment tumor volume is an important variable.

18F-FDG PET-CT scans have demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in Ewing sarcoma and are now routinely used to complete staging. In one institutional study, 18F-FDG PET had a very high correlation with bone scan; the investigators suggested that it could replace bone scan for the initial extent of disease evaluation.[5] This finding was confirmed in a single-institution retrospective review.[6] 18F-FDG PET-CT is more accurate than 18F-FDG PET alone in Ewing sarcoma.[7-9]

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy have been considered the standard of care for Ewing sarcoma. However, two retrospective studies showed that for patients (N = 141) who were evaluated by bone scan and/or PET scan and lung CT without evidence of metastases, bone marrow aspirates and biopsies were negative in every case.[5,10] A single-institution retrospective review of 504 patients with Ewing sarcoma identified 12 patients with bone marrow metastasis.[11] Only one patient was found to have bone marrow involvement without any other sites of metastatic disease, for an incidence of 1 per 367 (0.3%) in patients with clinically localized disease. The need for routine use of bone marrow aspirates and biopsies in patients without bone metastases is now in question.

For Ewing sarcoma, tumors are practically staged as localized or metastatic, and other staging systems are not commonly used. The tumor is defined as localized when, by clinical and imaging techniques, there is no spread beyond the primary site or regional lymph node involvement. Continuous extension into adjacent soft tissue may occur. If there is a question of regional lymph node involvement, pathological confirmation is indicated.

References

- Costelloe CM, Chuang HH, Daw NC: PET/CT of Osteosarcoma and Ewing Sarcoma. Semin Roentgenol 52 (4): 255-268, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tal AL, Doshi H, Parkar F, et al.: The Utility of 18FDG PET/CT Versus Bone Scan for Identification of Bone Metastases in a Pediatric Sarcoma Population and a Review of the Literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 43 (2): 52-58, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Meyer JS, Nadel HR, Marina N, et al.: Imaging guidelines for children with Ewing sarcoma and osteosarcoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group Bone Tumor Committee. Pediatr Blood Cancer 51 (2): 163-70, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mentzel HJ, Kentouche K, Sauner D, et al.: Comparison of whole-body STIR-MRI and 99mTc-methylene-diphosphonate scintigraphy in children with suspected multifocal bone lesions. Eur Radiol 14 (12): 2297-302, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Newman EN, Jones RL, Hawkins DS: An evaluation of [F-18]-fluorodeoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography, bone scan, and bone marrow aspiration/biopsy as staging investigations in Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60 (7): 1113-7, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ulaner GA, Magnan H, Healey JH, et al.: Is methylene diphosphonate bone scan necessary for initial staging of Ewing sarcoma if 18F-FDG PET/CT is performed? AJR Am J Roentgenol 202 (4): 859-67, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Völker T, Denecke T, Steffen I, et al.: Positron emission tomography for staging of pediatric sarcoma patients: results of a prospective multicenter trial. J Clin Oncol 25 (34): 5435-41, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gerth HU, Juergens KU, Dirksen U, et al.: Significant benefit of multimodal imaging: PET/CT compared with PET alone in staging and follow-up of patients with Ewing tumors. J Nucl Med 48 (12): 1932-9, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Treglia G, Salsano M, Stefanelli A, et al.: Diagnostic accuracy of ¹⁸F-FDG-PET and PET/CT in patients with Ewing sarcoma family tumours: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Skeletal Radiol 41 (3): 249-56, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kopp LM, Hu C, Rozo B, et al.: Utility of bone marrow aspiration and biopsy in initial staging of Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62 (1): 12-5, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cesari M, Righi A, Colangeli M, et al.: Bone marrow biopsy in the initial staging of Ewing sarcoma: Experience from a single institution. Pediatr Blood Cancer 66 (6): e27653, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment Option Overview for Ewing Sarcoma

It is important that patients be evaluated by specialists from the appropriate disciplines (e.g., medical oncologists, surgical or orthopedic oncologists, and radiation oncologists) as early as possible. Multidisciplinary review with radiologists and pathologists is often performed at sarcoma specialty centers.

Appropriate imaging studies of the suspected primary site are obtained before biopsy. To ensure that the biopsy incision is placed in an acceptable location, the surgical or orthopedic oncologist (who will perform the definitive surgery) is consulted on biopsy-incision placement. This is especially important if it is thought that the lesion can subsequently be totally excised after initial systemic therapy or if a limb salvage procedure may be attempted. It is almost never appropriate to attempt a primary resection of known Ewing sarcoma at initial diagnosis. With rare exceptions, Ewing sarcoma is sensitive to chemotherapy and will respond to initial systemic therapy. This therapy reduces the risk of tumor spread to surrounding tissues and makes ultimate surgery easier and safer. Biopsy should be from soft tissue as often as possible to avoid increasing the risk of fracture.[1] If the initial biopsy sample is obtained from bone, reserving some tissue without decalcification is required because decalcification denatures DNA and makes genomic profiling of tumor tissue impossible.[2] The pathologist is consulted before biopsy/surgery to ensure that the incision will not compromise the radiation port and that multiple types of adequate tissue samples are obtained. It is important to obtain fresh tissue, whenever possible, for cytogenetics and molecular pathology. A second option is to perform a needle biopsy, as long as adequate tissue is obtained for molecular studies.[3]

Table 5 describes the treatment options for localized, metastatic, and recurrent Ewing sarcoma.

| Treatment Group | Standard Treatment Options | |

|---|---|---|

| Localized Ewing sarcoma | Chemotherapy | |

| Local-control measures: | ||

| Surgery | ||

| Radiation therapy | ||

| High-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue | ||

| Metastatic Ewing sarcoma | Chemotherapy | |

| Surgery | ||

| Radiation therapy | ||

| Recurrent Ewing sarcoma | Chemotherapy (not considered standard treatment) | |

| Surgery (not considered standard treatment) | ||

| Radiation therapy (not considered standard treatment) | ||

| High-dose chemotherapy with stem cell support (not considered standard treatment) | ||

| Other therapies (not considered standard treatment) | ||

The successful treatment of patients with Ewing sarcoma requires systemic chemotherapy [4-10] in conjunction with surgery and/or radiation therapy for local tumor control.[11-15] In general, patients receive chemotherapy before instituting local-control measures. In patients who undergo surgery, surgical margins and histological response are considered in planning postoperative therapy. Patients with metastatic disease often have a good initial response to preoperative chemotherapy, but in most cases, the disease is only partially controlled or recurs.[16-21] Patients with lung as the only metastatic site have a better prognosis than do patients with metastases to bone and/or bone marrow. Adequate local control for metastatic sites, particularly bone metastases, may be an important consideration.[22]

Chemotherapy for Ewing Sarcoma

Multidrug chemotherapy for Ewing sarcoma always includes vincristine, doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and etoposide. Most protocols also use cyclophosphamide and some incorporate dactinomycin. The mode of administration and dose intensity of cyclophosphamide within courses differs markedly between protocols. A European Intergroup Cooperative Ewing Sarcoma Study (EICESS) trial suggested that 1.2 g of cyclophosphamide produced a similar event-free survival (EFS) compared with 6 g of ifosfamide in patients with lower-risk disease. The trial also identified a trend toward better EFS for patients with localized Ewing sarcoma and higher-risk disease when treatment included etoposide (GER-GPOH-EICESS-92 [NCT00002516]).[23][Level of evidence A1]

Protocols in the United States generally alternate courses of vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin (VDC) with courses of ifosfamide and etoposide (IE),[8] using interval compression.[24-26] For many years, European protocols generally combined vincristine, doxorubicin, and an alkylating agent with or without etoposide in a single treatment cycle.[10] After the completion of the randomized EURO EWING 2012 (EE2012) trial (see below), European investigators shifted to therapy with cycles of VDC alternating with cycles of IE.[27][Level of evidence B1] The duration of primary chemotherapy ranges from 6 months to approximately 1 year.

Evidence (chemotherapy):

- An international consortium of European countries conducted the EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 (NCT00020566) trial from 2000 to 2010.[28][Level of evidence A1] All patients received induction therapy with six cycles of vincristine, ifosfamide, doxorubicin, and etoposide (VIDE), followed by local control, and then one cycle of vincristine, dactinomycin, and ifosfamide (VAI). Patients were classified as standard risk if they had localized disease and good histological response to therapy or if they had localized tumors less than 200 mL in volume at presentation; they were treated with radiation therapy alone as local treatment. Standard-risk patients (n = 856) were randomly assigned to receive maintenance therapy with either seven cycles of vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide (VAC) or VAI.

- There was no significant difference in EFS or overall survival (OS) between patients who received VAC and patients who received VAI.

- The 3-year EFS rate for this low-risk population was 77%.

- It is difficult to compare this outcome with that of other large series because the study population excluded patients with poor response to initial therapy or patients with tumors more than 200 mL in volume who received local-control therapy with radiation alone. All other published series report results for all patients who present without clinically detectable metastasis; thus, these other series included patients with poor response and patients with larger primary tumors treated with radiation alone, all of whom were excluded from the EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 study.

- In a Children's Oncology Group (COG) study (COG-AEWS0031 [NCT00006734]), patients presenting without metastases were randomly assigned to receive cycles of VDC alternating with cycles of IE at either 2-week or 3-week intervals.[24]

- The administration of cycles of VDC/IE at 2-week intervals achieved superior EFS (5-year EFS rate, 73%) than did alternating cycles at 3-week intervals (5-year EFS rate, 65%). With longer follow-up, the advantage of interval-compressed chemotherapy was confirmed.[25]

- The 10-year EFS rate was 70% using interval-compressed chemotherapy, compared with 61% using standard-timing chemotherapy (P = .03). The 10-year OS rate was 76% using interval-compressed chemotherapy, compared with 69% using standard-timing chemotherapy (P = .04).

- The EE2012 trial was an international multicenter phase III study that included two randomized treatments, the European VIDE induction regimen and the North American standard VDC/IE induction regimen. Patients with both localized and metastatic Ewing sarcoma were eligible for the study.[27][Level of evidence B1]

- The hazard ratios (HRs) for EFS (0.71) and OS (0.62) favored VDC/IE over VIDE. The posterior probabilities were 99% for both EFS and OS, which showed that VDC/IE was superior.

- Rates of febrile neutropenia were higher with the VIDE regimen. There were no other major differences in acute toxicities between the two regimens.

- The benefit of VDC/IE over VIDE was seen across subgroups defined by patient age, sex, stage, tumor volume, or country of residence.

- The Brazilian Cooperative Study Group performed a multi-institutional trial that incorporated carboplatin into a risk-adapted intensive regimen in 175 children with localized or metastatic Ewing sarcoma.[29][Level of evidence B4]

- The investigators found significantly increased toxicity without an improvement in outcome with the addition of carboplatin.

- The COG performed a prospective randomized trial in patients with localized Ewing sarcoma. All patients received cycles of VDC and cycles of IE. Patients were then randomly assigned to receive or not receive additional experimental cycles of vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and topotecan.[26]

- The 5-year EFS rate was 78% (95% confidence interval [CI], 72%–82%) for those treated with experimental therapy and 79% (95% CI, 74%–83%) for patients treated with standard therapy.

- The experimental therapy did not significantly reduce the risk of events (EFS HR for experimental arm vs. standard arm, 0.86; 1-sided P = .19).

Local Control (Surgery and Radiation Therapy) for Ewing Sarcoma

Treatment approaches for Ewing sarcoma and therapeutic aggressiveness must be adjusted to maximize local control while also minimizing morbidity.

Surgery is the most commonly used form of local control.[30] Radiation therapy is an effective alternative modality for local control in cases where the functional or cosmetic morbidity of surgery is deemed too high by experienced surgical oncologists. However, in the immature skeleton, radiation therapy can cause subsequent deformities that may be more morbid than deformities from surgery. When complete surgical resection with pathologically negative margins is not anticipated, surgery is not typically performed, and definitive radiation is used instead. When pathologically positive margins are found, then postoperative radiation therapy is indicated. A multidisciplinary discussion between the experienced radiation oncologist and the surgeon is necessary to determine the best treatment options for local control for a given case. For some marginally resectable lesions, a combined approach of preoperative radiation therapy followed by resection can be used.

Timing of local control may impact outcome. A retrospective review from the National Cancer Database identified 1,318 patients with Ewing sarcoma.[31] Patients who initiated local therapy at 6 to 15 weeks had a 5-year OS rate of 78.7% and a 10-year OS rate of 70.3%, and patients who initiated local therapy after 16 weeks had a 5-year OS rate of 70.4% and a 10-year OS rate of 57.1% (P < .001). The difference in OS according to time to local therapy was more important in patients who received radiation therapy alone.

For patients with metastatic Ewing sarcoma, any benefit of combined surgery and radiation therapy compared with either therapy alone for local control is relatively less substantial because the overall prognosis of these patients is much worse than the prognosis of patients who have localized disease.

Randomized trials that directly compare surgery and radiation therapy do not exist, and their relative roles remain controversial. Although retrospective institutional series suggest better local control and survival with surgery than with radiation therapy, most of these studies are compromised by selection bias. An analysis using propensity scoring to adjust for clinical features that may influence the preference for surgery only, radiation only, or combined surgery and radiation demonstrated that similar EFS is achieved with each mode of local therapy.[30] Data for patients with pelvic primary Ewing sarcoma from a North American intergroup trial showed no difference in local control or survival based on local-control modality—surgery alone, radiation therapy alone, or surgery plus radiation therapy.[32]

The EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 (NCT00020566) trial prospectively treated 180 patients with pelvic primary tumors without clinically detectable metastatic disease.[33][Level of evidence B4] A retrospective analysis of outcomes for these patients showed improved survival for patients whose tumors were treated with combined radiation therapy and surgery. The study did not prospectively define criteria for the selection of local-control modalities, and the investigators did not have access to information that would allow them to clarify how decisions for local-control modalities were made. In nonsacral tumors, combined local treatment was associated with a lower local recurrence probability (14% [95% CI, 5%–23%] vs. 33% [95% CI, 19%–47%] at 5 years; P = .015) and a higher OS probability (72% [95% CI, 61%–83%] vs. 47% [95% CI, 33%–62%] at 5 years; P = .024), compared with surgery alone. Even in a subgroup of patients with wide surgical margins and a good histological response to induction treatment, the combined local treatment was associated with a higher OS probability (87% [95% CI, 74%–100%] vs. 51% [95% CI, 33%–69%] at 5 years; P = .009), compared with surgery alone. In patients with bone tumors who underwent surgical treatment—after controlling for tumor site in the pelvis, tumor volume, and surgical margin status—those who did not undergo complete removal of the affected bone (HR, 5.04; 95% CI, 2.07–12.24; P < .001), those with a poor histological response to induction chemotherapy (HR, 3.72; 95% CI, 1.51–9.21; P = .004), and those who did not receive additional radiation therapy (HR, 4.34; 95% CI, 1.71–11.05; P = .002) had a higher risk of death.

For patients who undergo gross-total resection with microscopic residual disease, a radiation therapy dose of 50.4 Gy is recommended. For patients treated with primary radiation therapy, the radiation dose is 55.8 Gy (45 Gy to the initial tumor volume and an additional 10.8 Gy to the postchemotherapy volume).[14,34]

Evidence (postoperative radiation therapy):

- Investigators from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital reported 39 patients with localized Ewing sarcoma who received both surgery and radiation.[14]

- The local failure rate for patients with positive margins was 17%, and the OS rate was 71%.

- The local failure rate for patients with negative margins was 5%, and the OS rate was 94%.

- In a large retrospective Italian study, 45 Gy of adjuvant radiation therapy for patients with inadequate margins did not appear to improve either local control or disease-free survival (DFS).[15]

- These investigators concluded that patients who are anticipated to have suboptimal surgery should be considered for definitive radiation therapy.

- The EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 (NCT00020566) study reported the outcomes of 599 patients who presented with localized disease and had surgical resection after initial chemotherapy with at least 90% necrosis of the primary tumor.[34][Level of evidence C2] The protocol recommended postoperative radiation therapy for patients with inadequate surgical margins, vertebral primary tumors, or thoracic tumors with pleural effusion, but the decision to use postoperative radiation therapy was left to the institutional investigator.

- Patients who received postoperative radiation therapy (n = 142) had a lower risk of failure than patients who did not receive postoperative radiation therapy, even after controlling for known prognostic factors, including age, sex, tumor site, clinical response, quality of resection, and histological necrosis. Most of the improvement was seen in a decreased risk of local recurrence. The improvement was greater in patients who had large tumors (>200 mL) and were assessed to have 100% necrosis than in patients who were assessed to have 90% to 100% necrosis.

- There is a clear interaction between systemic therapy and local-control modalities for both local control and DFS. The induction regimen used in the EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 study is less intense than the induction regimen used in contemporaneous protocols in the COG, and it is not appropriate to extrapolate the results from the EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 study to different systemic chemotherapy regimens.

Thoracic primary tumors

Evidence (surgery):

- The treatment and outcomes for 62 patients with thoracic Ewing sarcoma were reported from the Cooperative Weichteilsarkom Studiengruppe CWS-81, -86, -91, -96, and -2002P trials.[35]

- The 5-year OS rate was 58.7% (95% CI, 52.7%–64.7%), and the EFS rate was 52.8% (95% CI, 46.8%–58.8%).

- Patients with intrathoracic tumors (n = 24) had a worse outcome (EFS rate, 37.5% [95% CI, 27.5%–37.5%]) than patients with chest wall tumors (n = 38; EFS rate, 62.3% [95% CI, 54.3%–70.3%]; P = .008).

- Patients aged 10 years and younger (n = 38) had a better survival (EFS rate, 65.7% [95% CI, 57.7%–73.7%]) than patients older than 10 years (EFS rate, 31.3% [95% CI, 21.3%–41.3%]; P = .01).

- Tumor size of less than or equal to 5 cm (n = 15) was associated with significantly better survival (EFS rate, 93.3% [95% CI, 87.3%–99.3%]), compared with a tumor size greater than 5 cm (n = 47; EFS rate, 40% [95% CI, 33%–47%]; P = .002).