Ovarian Epithelial, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version

General Information About Ovarian Epithelial, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer

This PDQ summary addresses the staging and treatment of ovarian epithelial cancer, fallopian tube cancer (FTC), and primary peritoneal cancer (PPC).

Regardless of the site of origin, the hallmark of these cancers is their early peritoneal spread of metastases. The inclusion of FTC and PPC within the ovarian epithelial cancer designation is generally accepted because of much evidence that points to a common Müllerian epithelium derivation and similar management of these three neoplasms. The hypothesis that many high-grade serous ovarian cancers (the most common histological subtype) may arise from precursor lesions that originate in the fimbriae of the fallopian tubes has been supported by findings from risk-reducing surgeries in healthy women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 variants.[1] In addition, histologically similar cancers diagnosed as primary peritoneal carcinomas share molecular findings, such as loss or inactivation of the tumor-suppressor p53 and BRCA1 or BRCA2 proteins.[2] Therefore, high-grade serous adenocarcinomas arising from the fallopian tube and elsewhere in the peritoneal cavity, together with most ovarian epithelial cancers, represent extrauterine adenocarcinomas of Müllerian epithelial origin and are staged and treated similarly to ovarian cancer. Since 2000, FTC and PPC have usually been included in ovarian cancer clinical trials.[3]

Clear cell and endometrioid ovarian cancers that are linked to endometriosis have different gene-expression signatures, as do mucinous subtypes.[2]

Stromal and germ cell tumors are relatively uncommon and comprise fewer than 10% of cases. For more information, see Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors Treatment and Ovarian Borderline Tumors Treatment.

Incidence and Mortality

Epithelial carcinoma of the ovary is one of the most common gynecologic malignancies, with almost 50% of all cases occurring in women older than 65 years. It is the sixth most frequent cause of cancer death in women.[4,5]

Estimated new cases and deaths from ovarian cancer in the United States in 2025:[5]

- New cases: 20,890.

- Deaths: 12,730.

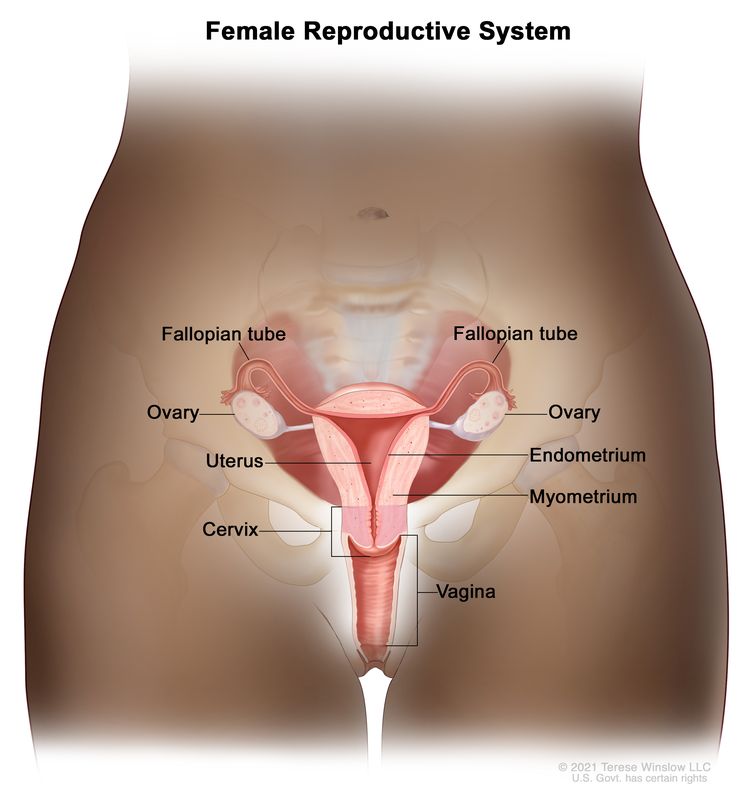

Anatomy

The fimbriated ends of the fallopian tubes are in close apposition to the ovaries and in the peritoneal space, as opposed to the corpus uteri (body of the uterus) that is located under a layer of peritoneum.

Risk Factors

Increasing age is the most important risk factor for most cancers. Other risk factors for ovarian (epithelial) cancer include:

- Family history of ovarian cancer.[6-8]

- A first-degree relative (e.g., mother, daughter, or sister) with the disease.

- Inherited risk.[9]

- Other hereditary conditions such as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC; also called Lynch syndrome).[6,9]

- Endometriosis.[11-13]

- Hormone therapy.[14,15]

- Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy.

- Obesity.[16-18]

- High body mass index.

- Tall height.[16-18]

Family history and genetic alterations

The most important risk factor for ovarian cancer is a history of ovarian cancer in a first-degree relative (mother, daughter, or sister). Approximately 20% of ovarian cancers are familial, and although most of these are linked to pathogenic variants in either the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene, several other genes have been implicated.[19,20] The risk is highest in women who have two or more first-degree relatives with ovarian cancer.[21] The risk is somewhat less for women who have one first-degree relative and one second-degree relative (grandmother or aunt) with ovarian cancer.

In most families affected with breast and ovarian cancer syndrome or site-specific ovarian cancer, genetic linkage to the BRCA1 locus on chromosome 17q21 has been identified.[22-24] BRCA2, also responsible for some instances of inherited ovarian and breast cancer, has been mapped by genetic linkage to chromosome 13q12.[25]

The lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer in patients with germline pathogenic variants in BRCA1 is substantially increased over that of the general population.[26,27] Two retrospective studies of patients with germline pathogenic variants in BRCA1 suggest that the women in these studies have improved survival compared with those without BRCA1 variants.[28,29][Level of evidence C1] Most women with BRCA1 variants probably have family members with a history of ovarian and/or breast cancer. Therefore, the women in these studies may have been more vigilant and inclined to participate in cancer screening programs that may have led to earlier detection.

For women at increased risk, prophylactic oophorectomy may be considered after age 35 years if childbearing is complete. A family-based study included 551 women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 variants. Of the 259 women who had undergone bilateral prophylactic oophorectomy, 2 (0.8%) developed subsequent papillary serous peritoneal carcinoma, and 6 (2.8%) had stage I ovarian cancer at the time of surgery. Of the 292 matched controls, 20% who did not have prophylactic surgery developed ovarian cancer. Prophylactic surgery was associated with a reduction in the risk of ovarian cancer that exceeded 90% (relative risk, 0.04; 95% confidence interval, 0.01–0.16), with an average follow-up of 9 years.[30] However, family-based studies may be associated with biases resulting from case selection and other factors that influence the estimate of benefit.[31] After a prophylactic oophorectomy, a small percentage of women may develop a PPC that is similar in appearance to ovarian cancer.[32] This risk of developing PPC is likely related to the presence of serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC) at the time of prophylactic oophorectomy. In a large study that pooled patients with BRCA variants from several sources, women with a STIC lesion were nearly 34 times more likely to develop PPC than women without such a lesion. This finding highlights the need for accurate and thorough pathological review of the prophylactic oophorectomy specimen to help with individual patient counseling.[33]

For more information, see Ovarian, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancers Prevention and BRCA1 and BRCA2: Cancer Risks and Management.

Clinical Presentation

Ovarian epithelial cancer, FTC, or PPC may not cause early signs or symptoms. When signs or symptoms do appear, cancer is often advanced. Signs and symptoms include:

- Pain, swelling, or a feeling of pressure in the abdomen or pelvis.

- Urinary urgency or frequency.

- Difficulty eating or feeling full.

- A lump in the pelvic area.

- Gastrointestinal problems such as gas, bloating, or constipation.

These symptoms often go unrecognized, leading to delays in diagnosis. Efforts have been made to enhance physician and patient awareness of the occurrence of these nonspecific symptoms.[34-38]

Screening procedures such as gynecologic assessment, vaginal ultrasonography, and cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) assay have had low predictive value in detecting ovarian cancer in women without special risk factors.[39,40] As a result of these confounding factors, annual mortality in ovarian cancer is approximately 65% of the incidence rate.

Most patients with ovarian cancer have widespread disease at presentation. Early peritoneal spread of the most common subtype of high-grade serous cancers may relate to serous cancers starting in the fimbriae of the fallopian tubes or in the peritoneum, readily explaining why such cancers are detected at an advanced stage. Conversely, high-grade serous cancers are underrepresented among stage I cancers of the ovary. Other types of ovarian cancers are, in fact, overrepresented in cancers detected in stages I and II. This type of ovarian cancer usually spreads via local shedding into the peritoneal cavity followed by implantation on the peritoneum and via local invasion of bowel and bladder. The incidence of positive nodes at primary surgery has been reported to be as high as 24% in patients with stage I disease, 50% in patients with stage II disease, 74% in patients with stage III disease, and 73% in patients with stage IV disease. The pelvic nodes were involved as often as the para-aortic nodes.[41] Tumor cells may also block diaphragmatic lymphatics. The resulting impairment of lymphatic drainage of the peritoneum is thought to play a role in development of ascites in ovarian cancer. Transdiaphragmatic spread to the pleura is common.

Diagnostic and Staging Evaluation

The following tests and procedures may be used in the diagnosis and staging of ovarian epithelial cancer, FTC, or PPC:

- Physical examination and history.

- Pelvic examination.

- CA-125 assay.

- Ultrasonography (pelvic or transvaginal).

- Computed tomography (CT) scan.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) scan.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

- Chest x-ray.

- Biopsy.

CA-125 levels can be elevated in other malignancies and benign gynecologic problems such as endometriosis. CA-125 levels and histology are used to diagnose epithelial ovarian cancer.[42,43]

Prognostic Factors

Prognosis for patients with ovarian cancer is influenced by multiple factors. Multivariate analyses suggest that the most important favorable prognostic factors include:[44-48]

- Younger age.

- Good performance status.

- Cell type other than mucinous or clear cell.

- Well-differentiated tumor.

- Early-stage disease.

- Absence of ascites.

- Lower disease volume before surgical debulking.

- Smaller residual tumor after primary cytoreductive surgery.

- BRCA1 or BRCA2 variant.

For patients with stage I disease, the most important prognostic factor associated with relapse is grade, followed by dense adherence and large-volume ascites.[49] Stage I tumors have a high proportion of low-grade serous cancers. These cancers have a derivation distinctly different from that of high-grade serous cancers, which usually present in stages III and IV. Many high-grade serous cancers originate in the fallopian tube and other areas of extrauterine Müllerian epithelial origin.

If the tumor is grade 3, densely adherent, or stage IC, the chance of relapse and death from ovarian cancer is as much as 30%.[49-52]

The use of DNA flow cytometric analysis of tumors from patients with stage I and stage IIA disease may identify those at high risk.[53] Patients with clear cell histology appear to have a worse prognosis.[54] Patients with a significant component of transitional cell carcinoma appear to have a better prognosis.[55]

Case-control studies suggest that women with BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants have improved responses to chemotherapy when compared with patients with sporadic epithelial ovarian cancer. This may be the result of a deficient homologous DNA repair mechanism in these tumors, which leads to increased sensitivity to chemotherapy agents.[56,57]

Follow-Up After Treatment

Because of the low specificity and sensitivity of the CA-125 assay, serial CA-125 monitoring of patients undergoing treatment for recurrence may be useful. However, whether that confers a net benefit has not yet been determined. There is little guidance about patient follow-up after initial induction therapy. Neither early detection by imaging nor by CA-125 elevation has been shown to alter outcomes.[58] For more information, see the Treatment of Recurrent or Persistent Ovarian Epithelial, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer section.

References

- Levanon K, Crum C, Drapkin R: New insights into the pathogenesis of serous ovarian cancer and its clinical impact. J Clin Oncol 26 (32): 5284-93, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Birrer MJ: The origin of ovarian cancer—is it getting clearer? N Engl J Med 363 (16): 1574-5, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dubeau L, Drapkin R: Coming into focus: the nonovarian origins of ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol 24 (Suppl 8): viii28-viii35, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- National Cancer Institute: SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Ovarian Cancer. Bethesda, Md: National Institutes of Health. Available online. Last accessed February 10, 2025.

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2025. American Cancer Society, 2025. Available online. Last accessed January 16, 2025.

- Bolton KL, Ganda C, Berchuck A, et al.: Role of common genetic variants in ovarian cancer susceptibility and outcome: progress to date from the Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium (OCAC). J Intern Med 271 (4): 366-78, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Weissman SM, Weiss SM, Newlin AC: Genetic testing by cancer site: ovary. Cancer J 18 (4): 320-7, 2012 Jul-Aug. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hunn J, Rodriguez GC: Ovarian cancer: etiology, risk factors, and epidemiology. Clin Obstet Gynecol 55 (1): 3-23, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Pal T, Akbari MR, Sun P, et al.: Frequency of mutations in mismatch repair genes in a population-based study of women with ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer 107 (10): 1783-90, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gayther SA, Pharoah PD: The inherited genetics of ovarian and endometrial cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev 20 (3): 231-8, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Poole EM, Lin WT, Kvaskoff M, et al.: Endometriosis and risk of ovarian and endometrial cancers in a large prospective cohort of U.S. nurses. Cancer Causes Control 28 (5): 437-445, 2017. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Pearce CL, Templeman C, Rossing MA, et al.: Association between endometriosis and risk of histological subtypes of ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis of case-control studies. Lancet Oncol 13 (4): 385-94, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mogensen JB, Kjær SK, Mellemkjær L, et al.: Endometriosis and risks for ovarian, endometrial and breast cancers: A nationwide cohort study. Gynecol Oncol 143 (1): 87-92, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lacey JV, Brinton LA, Leitzmann MF, et al.: Menopausal hormone therapy and ovarian cancer risk in the National Institutes of Health-AARP Diet and Health Study Cohort. J Natl Cancer Inst 98 (19): 1397-405, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Trabert B, Wentzensen N, Yang HP, et al.: Ovarian cancer and menopausal hormone therapy in the NIH-AARP diet and health study. Br J Cancer 107 (7): 1181-7, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Engeland A, Tretli S, Bjørge T: Height, body mass index, and ovarian cancer: a follow-up of 1.1 million Norwegian women. J Natl Cancer Inst 95 (16): 1244-8, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lahmann PH, Cust AE, Friedenreich CM, et al.: Anthropometric measures and epithelial ovarian cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Int J Cancer 126 (10): 2404-15, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Collaborative Group on Epidemiological Studies of Ovarian Cancer: Ovarian cancer and body size: individual participant meta-analysis including 25,157 women with ovarian cancer from 47 epidemiological studies. PLoS Med 9 (4): e1001200, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lynch HT, Watson P, Lynch JF, et al.: Hereditary ovarian cancer. Heterogeneity in age at onset. Cancer 71 (2 Suppl): 573-81, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Pennington KP, Swisher EM: Hereditary ovarian cancer: beyond the usual suspects. Gynecol Oncol 124 (2): 347-53, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Piver MS, Goldberg JM, Tsukada Y, et al.: Characteristics of familial ovarian cancer: a report of the first 1,000 families in the Gilda Radner Familial Ovarian Cancer Registry. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 17 (3): 169-76, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Miki Y, Swensen J, Shattuck-Eidens D, et al.: A strong candidate for the breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1. Science 266 (5182): 66-71, 1994. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Easton DF, Bishop DT, Ford D, et al.: Genetic linkage analysis in familial breast and ovarian cancer: results from 214 families. The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Am J Hum Genet 52 (4): 678-701, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Steichen-Gersdorf E, Gallion HH, Ford D, et al.: Familial site-specific ovarian cancer is linked to BRCA1 on 17q12-21. Am J Hum Genet 55 (5): 870-5, 1994. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wooster R, Neuhausen SL, Mangion J, et al.: Localization of a breast cancer susceptibility gene, BRCA2, to chromosome 13q12-13. Science 265 (5181): 2088-90, 1994. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Easton DF, Ford D, Bishop DT: Breast and ovarian cancer incidence in BRCA1-mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Am J Hum Genet 56 (1): 265-71, 1995. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Struewing JP, Hartge P, Wacholder S, et al.: The risk of cancer associated with specific mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 among Ashkenazi Jews. N Engl J Med 336 (20): 1401-8, 1997. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rubin SC, Benjamin I, Behbakht K, et al.: Clinical and pathological features of ovarian cancer in women with germ-line mutations of BRCA1. N Engl J Med 335 (19): 1413-6, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Aida H, Takakuwa K, Nagata H, et al.: Clinical features of ovarian cancer in Japanese women with germ-line mutations of BRCA1. Clin Cancer Res 4 (1): 235-40, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rebbeck TR, Lynch HT, Neuhausen SL, et al.: Prophylactic oophorectomy in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. N Engl J Med 346 (21): 1616-22, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Klaren HM, van't Veer LJ, van Leeuwen FE, et al.: Potential for bias in studies on efficacy of prophylactic surgery for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation. J Natl Cancer Inst 95 (13): 941-7, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Piver MS, Jishi MF, Tsukada Y, et al.: Primary peritoneal carcinoma after prophylactic oophorectomy in women with a family history of ovarian cancer. A report of the Gilda Radner Familial Ovarian Cancer Registry. Cancer 71 (9): 2751-5, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Steenbeek MP, van Bommel MHD, Bulten J, et al.: Risk of Peritoneal Carcinomatosis After Risk-Reducing Salpingo-Oophorectomy: A Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. J Clin Oncol 40 (17): 1879-1891, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Goff BA, Mandel L, Muntz HG, et al.: Ovarian carcinoma diagnosis. Cancer 89 (10): 2068-75, 2000. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Friedman GD, Skilling JS, Udaltsova NV, et al.: Early symptoms of ovarian cancer: a case-control study without recall bias. Fam Pract 22 (5): 548-53, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Smith LH, Morris CR, Yasmeen S, et al.: Ovarian cancer: can we make the clinical diagnosis earlier? Cancer 104 (7): 1398-407, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Goff BA, Mandel LS, Melancon CH, et al.: Frequency of symptoms of ovarian cancer in women presenting to primary care clinics. JAMA 291 (22): 2705-12, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Goff BA, Mandel LS, Drescher CW, et al.: Development of an ovarian cancer symptom index: possibilities for earlier detection. Cancer 109 (2): 221-7, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Partridge E, Kreimer AR, Greenlee RT, et al.: Results from four rounds of ovarian cancer screening in a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol 113 (4): 775-82, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- van Nagell JR, Miller RW, DeSimone CP, et al.: Long-term survival of women with epithelial ovarian cancer detected by ultrasonographic screening. Obstet Gynecol 118 (6): 1212-21, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Burghardt E, Girardi F, Lahousen M, et al.: Patterns of pelvic and paraaortic lymph node involvement in ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 40 (2): 103-6, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Berek JS, Knapp RC, Malkasian GD, et al.: CA 125 serum levels correlated with second-look operations among ovarian cancer patients. Obstet Gynecol 67 (5): 685-9, 1986. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Atack DB, Nisker JA, Allen HH, et al.: CA 125 surveillance and second-look laparotomy in ovarian carcinoma. Am J Obstet Gynecol 154 (2): 287-9, 1986. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Omura GA, Brady MF, Homesley HD, et al.: Long-term follow-up and prognostic factor analysis in advanced ovarian carcinoma: the Gynecologic Oncology Group experience. J Clin Oncol 9 (7): 1138-50, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

- van Houwelingen JC, ten Bokkel Huinink WW, van der Burg ME, et al.: Predictability of the survival of patients with advanced ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 7 (6): 769-73, 1989. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Neijt JP, ten Bokkel Huinink WW, van der Burg ME, et al.: Long-term survival in ovarian cancer. Mature data from The Netherlands Joint Study Group for Ovarian Cancer. Eur J Cancer 27 (11): 1367-72, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hoskins WJ, Bundy BN, Thigpen JT, et al.: The influence of cytoreductive surgery on recurrence-free interval and survival in small-volume stage III epithelial ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 47 (2): 159-66, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Thigpen T, Brady MF, Omura GA, et al.: Age as a prognostic factor in ovarian carcinoma. The Gynecologic Oncology Group experience. Cancer 71 (2 Suppl): 606-14, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dembo AJ, Davy M, Stenwig AE, et al.: Prognostic factors in patients with stage I epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol 75 (2): 263-73, 1990. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ahmed FY, Wiltshaw E, A'Hern RP, et al.: Natural history and prognosis of untreated stage I epithelial ovarian carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 14 (11): 2968-75, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Monga M, Carmichael JA, Shelley WE, et al.: Surgery without adjuvant chemotherapy for early epithelial ovarian carcinoma after comprehensive surgical staging. Gynecol Oncol 43 (3): 195-7, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kolomainen DF, A'Hern R, Coxon FY, et al.: Can patients with relapsed, previously untreated, stage I epithelial ovarian cancer be successfully treated with salvage therapy? J Clin Oncol 21 (16): 3113-8, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schueler JA, Cornelisse CJ, Hermans J, et al.: Prognostic factors in well-differentiated early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer 71 (3): 787-95, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Young RC, Walton LA, Ellenberg SS, et al.: Adjuvant therapy in stage I and stage II epithelial ovarian cancer. Results of two prospective randomized trials. N Engl J Med 322 (15): 1021-7, 1990. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gershenson DM, Silva EG, Mitchell MF, et al.: Transitional cell carcinoma of the ovary: a matched control study of advanced-stage patients treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 168 (4): 1178-85; discussion 1185-7, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Vencken PM, Kriege M, Hoogwerf D, et al.: Chemosensitivity and outcome of BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated ovarian cancer patients after first-line chemotherapy compared with sporadic ovarian cancer patients. Ann Oncol 22 (6): 1346-52, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Safra T, Borgato L, Nicoletto MO, et al.: BRCA mutation status and determinant of outcome in women with recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer treated with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin. Mol Cancer Ther 10 (10): 2000-7, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rustin GJ, van der Burg ME, Griffin CL, et al.: Early versus delayed treatment of relapsed ovarian cancer (MRC OV05/EORTC 55955): a randomised trial. Lancet 376 (9747): 1155-63, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

Cellular Classification of Ovarian Epithelial, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer

Table 1 describes the histological classification of ovarian epithelial cancer, fallopian tube cancer (FTC), and primary peritoneal cancer (PPC).

| Histological Classification | Histological Subtypes |

|---|---|

| FTC = fallopian tube cancer; PPC = primary peritoneal cancer. | |

| Serous cystomas | Serous benign cystadenomas. |

| Serous cystadenomas with proliferating activity of the epithelial cells and nuclear abnormalities but with no infiltrative destructive growth. | |

| Serous cystadenocarcinomas. | |

| Mucinous cystomas | Mucinous benign cystadenomas. |

| Mucinous cystadenomas with proliferating activity of the epithelial cells and nuclear abnormalities but with no infiltrative destructive growth (low malignant potential or borderline malignancy). | |

| Mucinous cystadenocarcinomas. | |

| Endometrioid tumors (similar to adenocarcinomas in the endometrium) | Endometrioid benign cysts. |

| Endometrioid tumors with proliferating activity of the epithelial cells and nuclear abnormalities but with no infiltrative destructive growth (low malignant potential or borderline malignancy). | |

| Endometrioid adenocarcinomas. | |

| Clear cell (mesonephroid) tumors | Benign clear cell tumors. |

| Clear cell tumors with proliferating activity of the epithelial cells and nuclear abnormalities but with no infiltrative destructive growth (low malignant potential or borderline malignancy). | |

| Clear cell cystadenocarcinomas. | |

| Unclassified tumors that cannot be allotted to one of the above groups | |

| No histology (cytology-only diagnosis) | |

| Other malignant tumors (malignant tumors other than those of the common epithelial types are not to be included with the categories listed above) | |

Stage Information for Ovarian Epithelial, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer

In the absence of extra-abdominal metastatic disease, definitive staging of ovarian cancer requires surgery. The role of surgery in patients with stage IV ovarian cancer and extra-abdominal disease is yet to be established. If disease appears to be limited to the ovaries or pelvis, it is essential at laparotomy to obtain peritoneal washings and to examine and biopsy or obtain cytological brushings of the following sites:

- Diaphragm.

- Both paracolic gutters.

- Pelvic peritoneum.

- Para-aortic and pelvic nodes.

- Infracolic omentum.[1]

The Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique (FIGO) Staging

The FIGO and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) have designated staging to define ovarian epithelial cancer. The FIGO-approved staging system for ovarian epithelial cancer, fallopian tube cancer (FTC), and primary peritoneal cancer (PPC) is the one most commonly used.[2,3]

| Stage | Definition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique. | ||

| aAdapted from FIGO Committee for Gynecologic Oncology.[2] | ||

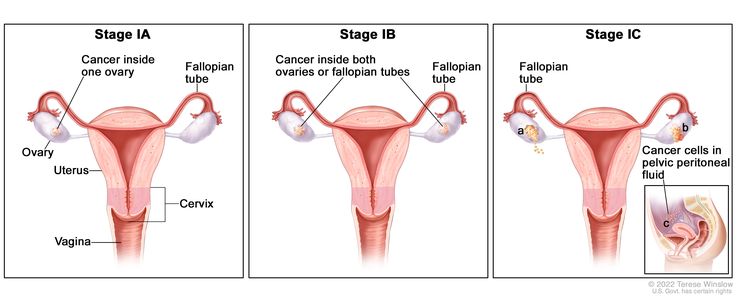

| I | Tumor confined to ovaries or fallopian tube(s). |

|

| IA | Tumor limited to one ovary (capsule intact) or fallopian tube; no tumor on ovarian or fallopian tube surface; no malignant cells in the ascites or peritoneal washings. | |

| IB | Tumor limited to both ovaries (capsules intact) or fallopian tubes; no tumor on ovarian or fallopian tube surface; no malignant cells in the ascites or peritoneal washings. | |

| IC | Tumor limited to one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes, with any of the following: | |

| IC1: Surgical spill. | ||

| IC2: Capsule ruptured before surgery or tumor on ovarian or fallopian tube surface. | ||

| IC3: Malignant cells in the ascites or peritoneal washings. | ||

| Stage | Definition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique. | ||

| aAdapted from FIGO Committee for Gynecologic Oncology.[2] | ||

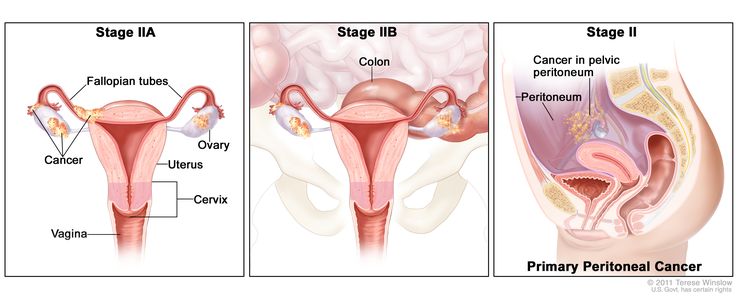

| II | Tumor involves one or both ovaries or fallopian tubes with pelvic extension (below pelvic brim) or primary peritoneal cancer. |

|

| IIA | Extension and/or implants on the uterus and/or fallopian tubes and/or ovaries. | |

| IIB | Extension to other pelvic intraperitoneal tissues. | |

| Stage | Definition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique. | ||

| aAdapted from FIGO Committee for Gynecologic Oncology.[2] | ||

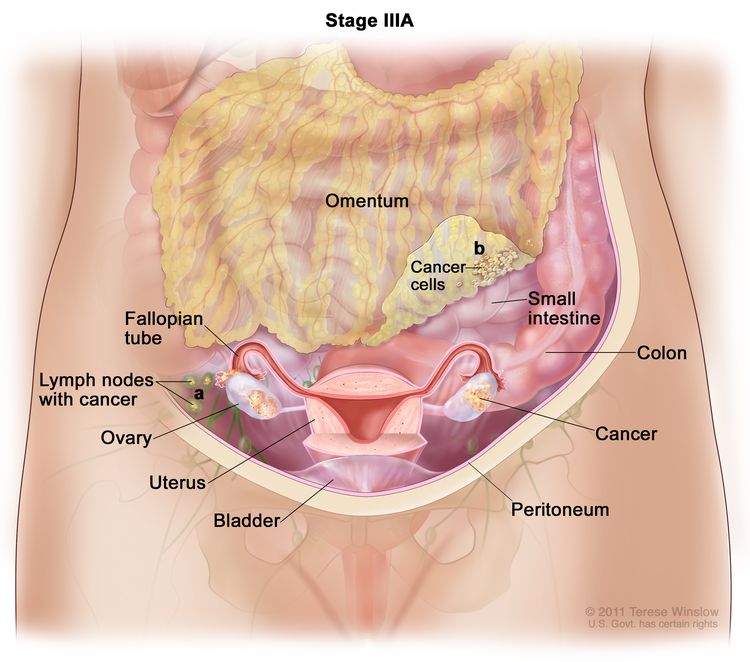

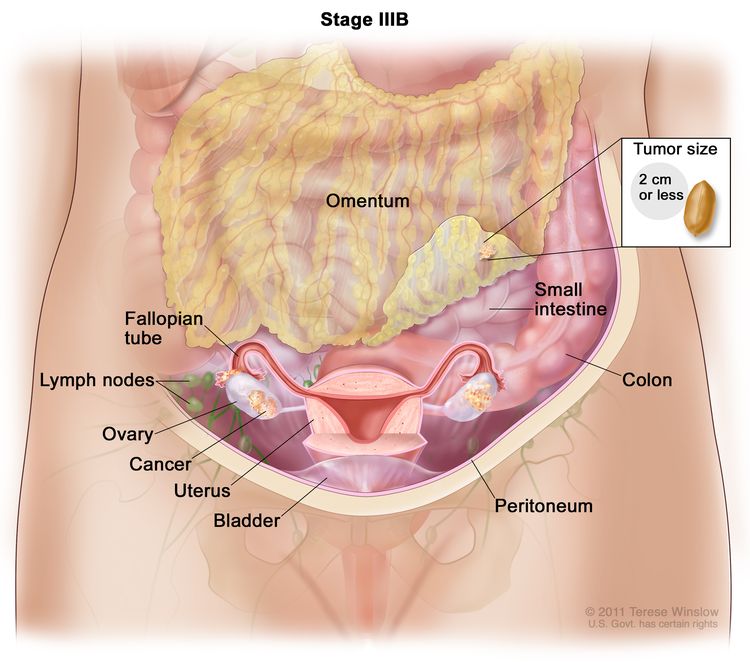

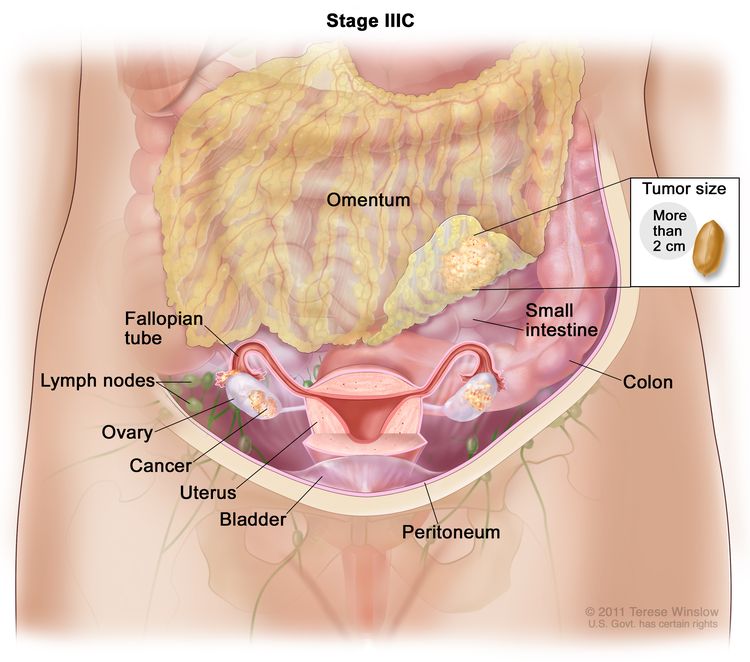

| III | Tumor involves one or both ovaries, or fallopian tubes, or primary peritoneal cancer, with cytologically or histologically confirmed spread to the peritoneum outside the pelvis and/or metastasis to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes. | |

| IIIA1 | Positive retroperitoneal lymph nodes only (cytologically or histologically proven): |

|

| IIIA1(I): Metastasis ≤10 mm in greatest dimension. | ||

| IIIA1(ii): Metastasis >10 mm in greatest dimension. | ||

| IIIA2 | Microscopic extrapelvic (above the pelvic brim) peritoneal involvement with or without positive retroperitoneal lymph nodes. | |

| IIIB | Macroscopic peritoneal metastases beyond the pelvis ≤2 cm in greatest dimension, with or without metastasis to the retroperitoneal lymph nodes. |

|

| IIIC | Macroscopic peritoneal metastasis beyond the pelvis >2 cm in greatest dimension, with or without metastasis to the retroperitoneal nodes (includes extension of tumor to capsule of liver and spleen without parenchymal involvement of either organ). |

|

| Stage | Definition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique. | ||

| aAdapted from FIGO Committee for Gynecologic Oncology.[2] | ||

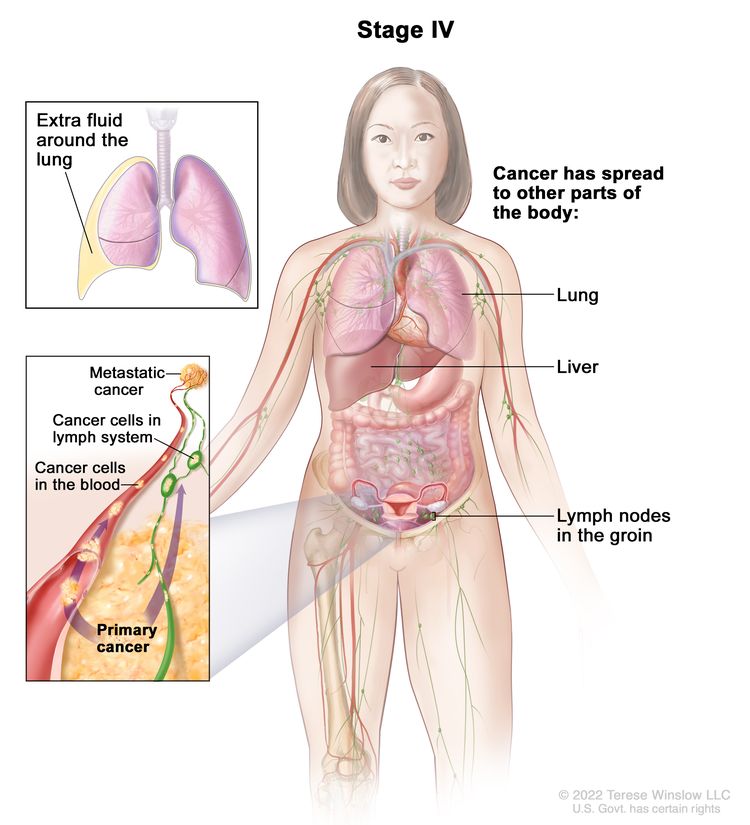

| IV | Distant metastasis excluding peritoneal metastases. |

|

| IVA | Pleural effusion with positive cytology. | |

| IVB | Parenchymal metastases and metastases to extra-abdominal organs (including inguinal lymph nodes and lymph nodes outside of the abdominal cavity). | |

References

- Hoskins WJ: Surgical staging and cytoreductive surgery of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer 71 (4 Suppl): 1534-40, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Berek JS, Renz M, Kehoe S, et al.: Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum: 2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 155 (Suppl 1): 61-85, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ovary, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal carcinoma. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp 681-90.

Treatment Option Overview for Ovarian Epithelial, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer

Treatment options for patients with all stages of ovarian epithelial cancer, fallopian tube cancer (FTC), and primary peritoneal cancer (PPC) have consisted of surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy.

Early stage refers to stages I and II. However, because of high recurrence rates for stage II patients in early-stage disease trials, patients with stage II cancers have been included with patients who have more advanced-stage cancer in Gynecologic Oncology Group clinical trials since 2009. Going forward, stage I will remain a separate category for treatment considerations, but high-grade serous stage II cancers are likely to be included with more advanced stages.

Numerous clinical trials are in progress to refine existing therapies and test the value of different approaches to postoperative drug and radiation therapy. Patients with any stage of ovarian cancer are appropriate candidates for clinical trials.[1,2] Information about ongoing clinical trials is available from the NCI website.

The treatment options for ovarian epithelial cancer, FTC, and PPC are presented in Table 6.

Capecitabine and Fluorouracil Dosing

The DPYD gene encodes an enzyme that catabolizes pyrimidines and fluoropyrimidines, like capecitabine and fluorouracil. An estimated 1% to 2% of the population has germline pathogenic variants in DPYD, which lead to reduced DPD protein function and an accumulation of pyrimidines and fluoropyrimidines in the body.[3,4] Patients with the DPYD*2A variant who receive fluoropyrimidines may experience severe, life-threatening toxicities that are sometimes fatal. Many other DPYD variants have been identified, with a range of clinical effects.[3-5] Fluoropyrimidine avoidance or a dose reduction of 50% may be recommended based on the patient's DPYD genotype and number of functioning DPYD alleles.[6-8] DPYD genetic testing costs less than $200, but insurance coverage varies due to a lack of national guidelines.[9] In addition, testing may delay therapy by 2 weeks, which would not be advisable in urgent situations. This controversial issue requires further evaluation.[10]

References

- Ozols RF, Young RC: Ovarian cancer. Curr Probl Cancer 11 (2): 57-122, 1987 Mar-Apr. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Cannistra SA: Cancer of the ovary. N Engl J Med 329 (21): 1550-9, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sharma BB, Rai K, Blunt H, et al.: Pathogenic DPYD Variants and Treatment-Related Mortality in Patients Receiving Fluoropyrimidine Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 26 (12): 1008-1016, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lam SW, Guchelaar HJ, Boven E: The role of pharmacogenetics in capecitabine efficacy and toxicity. Cancer Treat Rev 50: 9-22, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Shakeel F, Fang F, Kwon JW, et al.: Patients carrying DPYD variant alleles have increased risk of severe toxicity and related treatment modifications during fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy. Pharmacogenomics 22 (3): 145-155, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Amstutz U, Henricks LM, Offer SM, et al.: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for Dihydropyrimidine Dehydrogenase Genotype and Fluoropyrimidine Dosing: 2017 Update. Clin Pharmacol Ther 103 (2): 210-216, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Henricks LM, Lunenburg CATC, de Man FM, et al.: DPYD genotype-guided dose individualisation of fluoropyrimidine therapy in patients with cancer: a prospective safety analysis. Lancet Oncol 19 (11): 1459-1467, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lau-Min KS, Varughese LA, Nelson MN, et al.: Preemptive pharmacogenetic testing to guide chemotherapy dosing in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies: a qualitative study of barriers to implementation. BMC Cancer 22 (1): 47, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Brooks GA, Tapp S, Daly AT, et al.: Cost-effectiveness of DPYD Genotyping Prior to Fluoropyrimidine-based Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Colon Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 21 (3): e189-e195, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Baker SD, Bates SE, Brooks GA, et al.: DPYD Testing: Time to Put Patient Safety First. J Clin Oncol 41 (15): 2701-2705, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Low-Grade Serous Carcinoma

Treatment Options for Low-Grade Serous Carcinoma

Low-grade serous carcinoma (LGSC), also known as invasive micropapillary serous carcinoma, arises either from serous borderline tumors or de novo. These tumors are uncommon, making up 5% of ovarian carcinomas, and occur in younger women. These tumors are associated with a better clinical prognosis than high-grade serous carcinomas. Molecular characterization of LGSC detected a lower frequency of TP53 variants, greater expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors, and a higher prevalence of BRAF and NRAS variants.[1] Unlike patients with high-grade histologies, patients with LGSC often do not have a markedly elevated CA-125 level at the time of diagnosis.[2] LGSC is seen in patients with variants in homologous recombination repair genes. The frequency of variants in homologous recombination repair genes is much lower in patients with LGSC (around 11%) than in patients with high-grade histologies (27%).[3]

Treatment approaches for patients with recurrent disease can include cytoreductive surgery, cytotoxic chemotherapy, hormonal therapy, or targeted agents.

Treatment options for LGSC include:

- Surgery with or without chemotherapy.

- Secondary cytoreductive surgery.

- Targeted therapies.

- Hormone therapy alone or combined with chemotherapy (under clinical evaluation [NCT04095364]).

Surgery with or without chemotherapy

While complete cytoreductive surgery is a major component of the treatment approach to LGSC, these tumors tend to be chemoresistant.[4] Despite this, given the lack of evidence to support alternative therapies, many patients receive a platinum and taxane chemotherapy doublet similar to that used in more invasive ovarian cancer. Patients requiring neoadjuvant chemotherapy before debulking surgery have a worse outcome than those undergoing primary debulking surgery.[5]

Secondary cytoreductive surgery

Evidence (secondary cytoreductive surgery):

- A single-institution retrospective review evaluated secondary cytoreductive surgery performed between 1995 and 2002 in 41 patients with recurrent LGSC. The study concluded that secondary cytoreduction is beneficial.[6][Level of evidence C3] The median time from primary tumor debulking until secondary cytoreduction was 33.2 months.

- Thirty-two patients (78%) had gross residual disease at completion of secondary cytoreduction.

- Patients with no gross residual disease after secondary cytoreduction had a median progression-free survival (PFS) of 60.3 months, compared with 10.7 months for those with gross residual disease (P = .008).

- After secondary cytoreduction surgery, the overall survival (OS) was 93.6 months for those with no gross residual disease and 45.8 months for those with gross residual disease (P = .04).

Targeted therapies

As LGSC is relatively chemoresistant, attention has focused on targeted therapies.

Evidence (targeted therapies):

- Anastrozole: Estrogen receptor (ER) expression is noted in most LGSCs and is a potential target. The PARAGON phase II basket trial evaluated the activity of anastrozole in patients with ER-positive tumors, including 36 patients with recurrent LGSC.[7][Level of evidence C3]

- The trial demonstrated clinical benefit in 61% of patients at 6 months and 34% of patients at 12 months. Notably, the study included patients with LGSC and other ER-positive tumors.

- The median duration of clinical benefit was 9.5 months.

- Trametinib: Trametinib is a selective, reversible, allosteric inhibitor of MEK1/MEK2. A recent international, randomized, multicenter, phase II/III trial evaluated trametinib in patients with LGSC. An unlimited number of prior therapies, including chemotherapy or hormone therapy, was allowed. Patients must have received at least one prior platinum-based regimen, but not all five standard-of-care drugs. Patients received either oral trametinib (2 mg once daily) or the standard of care with the physician’s choice of chemotherapy (paclitaxel, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, topotecan, oral letrozole, or oral tamoxifen).[8][Level of evidence B1]

- The median PFS was 13.0 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 9.9–15.0) in the trametinib group and 7.5 months (95% CI, 5.6–9.9) in the standard-of-care group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.48; 95% CI, 0.36–0.64; one-sided P < .0001).

- A post hoc analysis was performed on a subgroup of 87 patients who were preplanned to receive letrozole if randomly assigned to the standard-of-care group. The PFS was 15.0 months (95% CI, 7.7–23.1) in the trametinib group and 10.6 months (95% CI, 6.5–12.8) in the letrozole group (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.36–0.95; one-sided P = .0085).

- The overall response rate was 26% (34 of 130 patients) in the trametinib group. An additional 59% of patients (77 of 130) had stable disease for at least 8 weeks.

- The median OS was 37.6 months (95% CI, 32.0–not evaluable) in the trametinib group and 29.2 months (95% CI, 23.5–51.6) in the standard-of-care group (HRdeath, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.51–1.12; one-sided P = .056).

- There was no evidence that BRAF, KRAS, or NRAS variant status predicted PFS.

- Binimetinib: MILO/ENGOT-ov11 (NCT01849874) was a phase III trial of binimetinib, a small molecule inhibitor of MEK1/MEK2. The trial included 303 patients with recurrent LGSC who had received one to three prior lines of chemotherapy. Patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive either binimetinib (45 mg orally twice daily) or physician’s choice of chemotherapy (pegylated liposomal doxorubicin, paclitaxel, or topotecan).[9]

- The median PFS was 9.1 months (95% CI, 7.3–11.3) for patients who received binimetinib and 10.6 months (95% CI, 9.2–14.5) for patients who received chemotherapy. The study closed early according to the prespecified futility boundary.

- The overall response rate was 16% for patients who received binimetinib (including 32 patients with complete/partial responses), and 13% for patients who received chemotherapy (including 13 patients with complete/partial responses).

- The median duration of response was 8.1 months (range, 0.03 to ≥12.0) for patients who received binimetinib and 6.7 months (range, 0.03 to ≥9.7) for patients who received chemotherapy.

- The OS was 25.3 months for patients who received binimetinib and 20.8 months for patients who received chemotherapy.

- OS was similar and viewed as no better or worse than chemotherapy.

- A post hoc analysis was conducted on tumor molecular testing samples from 215 patients. KRAS variants were seen in 32% to 34% of patients. The analysis showed that KRAS variants were associated with a response to treatment with binimetinib (odds ratio, 3.4; 95% CI, 1.53–7.66; unadjusted P = .003) and with prolonged PFS in patients treated with binimetinib (median PFS: KRAS variant, 17.7 months [95% CI, 12–not reached]; KRAS wild-type, 10.8 months [95% CI, 5.5–16.7]; P = .006).

- Bevacizumab: Bevacizumab is an anti-VEGFA monoclonal antibody. A single institution enrolled 13 patients with LGSC and 4 patients with borderline tumors. Two patients received bevacizumab as a single agent while the other patients received bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy (i.e., paclitaxel, topotecan, oral cyclophosphamide, gemcitabine, or gemcitabine and carboplatin).[10][Level of evidence C3]

- After a median duration of 23 weeks (range, 6–79.4), there were no patients with a complete response and six patients with partial responses (five of whom had received concurrent paclitaxel, and one who received concurrent gemcitabine). The overall response rate was 40% among all evaluable patients, and 55% among the subgroup of LGSC patients.

- Ribociclib and letrozole: GOG-3026 (NCT03673124) was a phase II trial evaluating the combination of ribociclib and letrozole in patients with recurrent LGSC. Patients received ribociclib, a CDK4/6 inhibitor, at 600 mg daily on a 3-weeks-on/1-week-off schedule, plus 2.5 mg of oral letrozole once daily for a 28-day cycle.[11]

- The overall response rate was 23% (90% CI, 13.4%–35.1%), and the clinical benefit rate was 97% (90% CI, 67.2%–88.2%).

- The median duration of response was 19.1 months. The median PFS was 19.1 months, and the median OS was not reached.

- Selumetinib: Selumetinib is a selective small molecule inhibitor of MEK1/MEK2. A phase II study included 52 patients with recurrent LGSC who received 50 mg of selumetinib twice daily until progression.[12][Level of evidence C3]

- There were 8 patients (15%) with complete responses, 7 patients (13%) with partial responses, and 34 patients (65%) with stable disease.

- The median time to response was 4.8 months, and the median duration of response was 10.5 months.

- The median PFS was 11 months, and 63% of patients had a PFS of more than 6 months.

- Responses were irrespective of BRAF or KRAS variant status.

- Imatinib: LGSC has a high expression of PDGFRB and BCR::ABL1. A phase II study evaluated imatinib mesylate in patients with platinum-resistant recurrent LGSC. The trial enrolled 13 patients who had received at least four prior lines of platinum- and/or taxane-containing chemotherapy and had been screened for a targeted biomarker (i.e., c-kit, PDGFRB, or BCR::ABL1). Patients received 600 mg of imatinib mesylate daily for 6 weeks.[13]

- There was no evidence of efficacy in patients who received imatinib mesylate despite high expression of PDGFRB.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Gershenson DM: Low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum. Ann Oncol 27 (Suppl 1): i45-i49, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Fader AN, Java J, Krivak TC, et al.: The prognostic significance of pre- and post-treatment CA-125 in grade 1 serous ovarian carcinoma: a gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 132 (3): 560-5, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Norquist BM, Brady MF, Harrell MI, et al.: Mutations in Homologous Recombination Genes and Outcomes in Ovarian Carcinoma Patients in GOG 218: An NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Clin Cancer Res 24 (4): 777-783, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gershenson DM, Sun CC, Lu KH, et al.: Clinical behavior of stage II-IV low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol 108 (2): 361-8, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Scott SA, Llaurado Fernandez M, Kim H, et al.: Low-grade serous carcinoma (LGSC): A Canadian multicenter review of practice patterns and patient outcomes. Gynecol Oncol 157 (1): 36-45, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Crane EK, Sun CC, Ramirez PT, et al.: The role of secondary cytoreduction in low-grade serous ovarian cancer or peritoneal cancer. Gynecol Oncol 136 (1): 25-9, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tang M, O'Connell RL, Amant F, et al.: PARAGON: A Phase II study of anastrozole in patients with estrogen receptor-positive recurrent/metastatic low-grade ovarian cancers and serous borderline ovarian tumors. Gynecol Oncol 154 (3): 531-538, 2019. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gershenson DM, Miller A, Brady WE, et al.: Trametinib versus standard of care in patients with recurrent low-grade serous ovarian cancer (GOG 281/LOGS): an international, randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 399 (10324): 541-553, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Monk BJ, Grisham RN, Banerjee S, et al.: MILO/ENGOT-ov11: Binimetinib Versus Physician's Choice Chemotherapy in Recurrent or Persistent Low-Grade Serous Carcinomas of the Ovary, Fallopian Tube, or Primary Peritoneum. J Clin Oncol 38 (32): 3753-3762, 2020. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Grisham RN, Iyer G, Sala E, et al.: Bevacizumab shows activity in patients with low-grade serous ovarian and primary peritoneal cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 24 (6): 1010-4, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Slomovitz B, Deng W, Killion J, et al.: GOG 3026 A phase II trial of letrozole + ribociclib in women with recurrent low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary, fallopian tube or peritoneum: A GOG foundation study. [Abstract] Gynecol Oncol 176 (Suppl 1): A-001, S2, 2023.

- Farley J, Brady WE, Vathipadiekal V, et al.: Selumetinib in women with recurrent low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 14 (2): 134-40, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Noguera IR, Sun CC, Broaddus RR, et al.: Phase II trial of imatinib mesylate in patients with recurrent platinum- and taxane-resistant low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary, peritoneum, or fallopian tube. Gynecol Oncol 125 (3): 640-5, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Early-Stage Ovarian Epithelial, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer

Early stage refers to stage I and stage II. However, because of high recurrence rates for stage II patients in early-stage disease trials, patients with stage II cancers have been included with patients who have more advanced-stage cancer in Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) clinical trials since 2009. Going forward, stage I will remain a separate category for treatment considerations, but high-grade serous stage II cancers are likely to be included with more advanced stages.

Treatment Options for Early-Stage Ovarian Epithelial Cancer, FTC, and PPC

Treatment options for early-stage ovarian epithelial cancer, fallopian tube cancer (FTC), and primary peritoneal cancer (PPC) include:

Surgery with or without chemotherapy

If the tumor is well differentiated or moderately well differentiated, surgery alone may be adequate treatment for patients with stage IA or IB disease. Surgery includes hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and omentectomy. The undersurface of the diaphragm is visualized and biopsied. Biopsies of the pelvic and abdominal peritoneum and the pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes are also performed. Peritoneal washings are routinely obtained.[1,2] In patients who desire childbearing and have grade 1 tumors, unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy may be associated with a low risk of recurrence.[3]

In the United States, except for the most favorable subset of patients (those with stage IA well-differentiated disease), evidence based on double-blinded, randomized, controlled trials with total mortality end points supports adjuvant treatment with cisplatin, carboplatin, and paclitaxel.

Evidence (surgery with or without chemotherapy):

- In two large European trials, the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Adjuvant ChemoTherapy in Ovarian Neoplasm trial (EORTC-ACTION) and International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm trial (MRC-ICON1 [NCT00002477]), patients with stage IA (grade 2) and stage IB (grade 3), all stage IC and stage II ovarian epithelial, and all stage I and stage IIA clear cell carcinoma were randomly assigned to receive adjuvant chemotherapy or observation.[4-6]

- The EORTC-ACTION trial required at least four cycles of carboplatin or cisplatin-based chemotherapy as treatment. Although surgical staging criteria were monitored, inadequate staging was not an exclusion criterion.[4]

- Recurrence-free survival (RFS) was improved for patients in the adjuvant chemotherapy arm (hazard ratio [HR], 0.63; P = .02), but overall survival (OS) was not affected (HR, 0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.44–1.08; P = .10).

- OS was improved by chemotherapy in the subset of patients with inadequate surgical staging.

- The MRC-ICON1 trial randomly assigned patients to receive six cycles of single-agent carboplatin or cisplatin or platinum-based chemotherapy (usually cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin) versus observation and had entry criteria similar to the EORTC-ACTION trial; however, the MRC-ICON1 trial did not monitor whether adequate surgical staging was performed.[5] When the results of the trials were combined, the difference in OS achieved statistical significance.

- Both RFS and OS were significantly improved; the 5-year survival rates were 79% for patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy versus 70% for those who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy.

- An analysis of pooled data from both studies demonstrated the following results:[6][Level of evidence A1]

- Patients who received chemotherapy showed significant improvement in RFS (HR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.50–0.82; P = .001) and OS (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.50–0.90; P = .008). The 5-year OS rate was 82% for patients who received chemotherapy and 74% for patients who underwent observation (difference, 8%; 95% CI, 2%–12%).[6][Level of evidence A1]

- An accompanying editorial emphasized that the focus of subsequent trials must be to identify patients who do not require additional therapy among the early ovarian cancer subset.[7] Optimal staging is one way to better identify these patients.

- The EORTC-ACTION trial required at least four cycles of carboplatin or cisplatin-based chemotherapy as treatment. Although surgical staging criteria were monitored, inadequate staging was not an exclusion criterion.[4]

- The GOG-0157 trial evaluated whether six cycles of chemotherapy were superior to three cycles for patients with early-stage, high-risk epithelial ovarian cancer after primary surgery. Eligible patients were those with stage IA grade 3 or clear cell histology, stage IB grade 3 or clear cell histology, all stage IC, and all stage II. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either three or six cycles of the combination of paclitaxel (175 mg/m2 administered over 3 hours) and carboplatin dosed (area under the curve, 7.5) over 30 minutes and given every 21 days. The primary end point was RFS, and the study was powered to detect a 50% decrease in the recurrence rate at 5 years. A total of 427 patients were eligible.[8]

- No significant difference in cumulative incidence of recurrence was found when three cycles (25.4%) were compared with six cycles (20.1%) (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.5–1.13) or OS for three cycles (81%) versus six cycles (83%) (HR, 1.02; P = .94).[8][Level of evidence B1]

- As expected, the use of six cycles was associated with increased grade 3 or 4 neurological toxic effects and increased grade 4 hematologic toxic effects.

- Although surgical staging was required for study entry, an audit revealed that 29% of the patients had either incomplete documentation of their surgery or insufficient surgical effort.

- In a post hoc analysis of the patients who underwent complete surgical staging, three additional cycles of chemotherapy decreased the risk of recurrence by only 3%. The cumulative incidence of recurrence within 5 years was 18% for women with stage I disease and 33% for women with stage II disease.

Given the increased risk of recurrence in patients with stage II disease and in those classified as having high-grade serous cancer, the GOG after 2007 opted to include patients with stage II disease in advanced ovarian cancer trials (for more information, see the Treatment of Advanced-Stage Ovarian Epithelial, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer section). Although the routine use of six cycles of chemotherapy is promulgated by guidelines, on subset analyses it is a source of controversy. Platinum-based chemotherapy including paclitaxel for three or six cycles has been evaluated by the GOG in additional trials that included prolonged maintenance paclitaxel, before phasing out early-stage clinical trials.

- Patients with stage II ovarian cancer were enrolled in a Japanese Gynecology Oncology Group study (JGOG-3016 [NCT00226915]) that tested a weekly dosing schedule versus the conventional every-3-week dosing schedule in first-line ovarian cancer.[9-11]

The following treatments have been largely displaced by the adoption of carboplatin plus paclitaxel for early stages of high-grade ovarian cancers:

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Young RC, Decker DG, Wharton JT, et al.: Staging laparotomy in early ovarian cancer. JAMA 250 (22): 3072-6, 1983. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Fader AN, Java J, Ueda S, et al.: Survival in women with grade 1 serous ovarian carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol 122 (2 Pt 1): 225-32, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Zanetta G, Chiari S, Rota S, et al.: Conservative surgery for stage I ovarian carcinoma in women of childbearing age. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 104 (9): 1030-5, 1997. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Trimbos JB, Vergote I, Bolis G, et al.: Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy and surgical staging in early-stage ovarian carcinoma: European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer-Adjuvant ChemoTherapy in Ovarian Neoplasm trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 95 (2): 113-25, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Colombo N, Guthrie D, Chiari S, et al.: International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm trial 1: a randomized trial of adjuvant chemotherapy in women with early-stage ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 95 (2): 125-32, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Trimbos JB, Parmar M, Vergote I, et al.: International Collaborative Ovarian Neoplasm trial 1 and Adjuvant ChemoTherapy In Ovarian Neoplasm trial: two parallel randomized phase III trials of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with early-stage ovarian carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 95 (2): 105-12, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Young RC: Early-stage ovarian cancer: to treat or not to treat. J Natl Cancer Inst 95 (2): 94-5, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bell J, Brady MF, Young RC, et al.: Randomized phase III trial of three versus six cycles of adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel in early stage epithelial ovarian carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 102 (3): 432-9, 2006. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Katsumata N, Yasuda M, Takahashi F, et al.: Dose-dense paclitaxel once a week in combination with carboplatin every 3 weeks for advanced ovarian cancer: a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 374 (9698): 1331-8, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Katsumata N, Yasuda M, Isonishi S, et al.: Long-term results of dose-dense paclitaxel and carboplatin versus conventional paclitaxel and carboplatin for treatment of advanced epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer (JGOG 3016): a randomised, controlled, open-label trial. Lancet Oncol 14 (10): 1020-6, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Scambia G, Salutari V, Amadio G: Controversy in treatment of advanced ovarian cancer. Lancet Oncol 14 (10): 920-1, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Vergote IB, Vergote-De Vos LN, Abeler VM, et al.: Randomized trial comparing cisplatin with radioactive phosphorus or whole-abdomen irradiation as adjuvant treatment of ovarian cancer. Cancer 69 (3): 741-9, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Piver MS, Lele SB, Bakshi S, et al.: Five and ten year estimated survival and disease-free rates after intraperitoneal chromic phosphate; stage I ovarian adenocarcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol 11 (5): 515-9, 1988. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bolis G, Colombo N, Pecorelli S, et al.: Adjuvant treatment for early epithelial ovarian cancer: results of two randomised clinical trials comparing cisplatin to no further treatment or chromic phosphate (32P). G.I.C.O.G.: Gruppo Interregionale Collaborativo in Ginecologia Oncologica. Ann Oncol 6 (9): 887-93, 1995. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Piver MS, Malfetano J, Baker TR, et al.: Five-year survival for stage IC or stage I grade 3 epithelial ovarian cancer treated with cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol 46 (3): 357-60, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- McGuire WP: Early ovarian cancer: treat now, later or never? Ann Oncol 6 (9): 865-6, 1995. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Advanced-Stage Ovarian Epithelial, Fallopian Tube, and Primary Peritoneal Cancer

Treatment options for patients with all stages of ovarian epithelial cancer, fallopian tube cancer (FTC), and primary peritoneal cancer (PPC) have consisted of surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy. Because of high recurrence rates for stage II patients in early-stage disease trials, patients with stage II cancers have been included with patients who have more advanced-stage cancer in Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) clinical trials since 2009. Going forward, stage I will remain a separate category for treatment considerations, but high-grade serous stage II cancers are likely to be included with more advanced stages.

The most common approach to advanced ovarian cancer is surgery followed by adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy. Published trials, most with primary end points of progression-free survival (PFS), are listed in Table 7. A PFS end point was endorsed by the Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIC), but subsequently it was questioned in a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by the GCIC.[1] After a MEDLINE search of randomized clinical trials of newly-diagnosed patients with ovarian epithelial cancer, FTC, or PPC, all studies with a minimum sample of 60 patients published from 2001 through 2016 were used to extract PFS and overall survival (OS) at an individual level. The PFS was mostly based on measurement of CA-125 levels confirmed by radiological examination or by GCIC criteria. Of 17 trials that were individually assessed, five tested the addition of maintenance therapy, seven tested additional induction drugs, and five tested intensification therapy. No poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor trials were included in this meta-analysis. The analysis concluded that PFS is not an adequate surrogate for OS, but it was limited by the narrow range of treatment effects observed and by poststudy treatments.

Treatment Options for Advanced-Stage Ovarian Epithelial Cancer, FTC, and PPC

Treatment options for advanced-stage ovarian epithelial cancer, FTC, and PPC include:

- Surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy.

- Surgery before or after platinum-based chemotherapy and/or additional consolidation therapy.

- Surgery before or after platinum-based chemotherapy and the addition of bevacizumab to induction therapy and/or consolidation therapy.

- Surgery after platinum-based chemotherapy and the addition of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC).

- Surgery before or after platinum-based chemotherapy and the addition of PARP inhibitors to induction therapy and/or consolidation therapy.

- Chemotherapy for patients who cannot have surgery (although the impact on OS has not been proven).

Platinum-based chemotherapy is the initial treatment for all patients diagnosed with advanced disease who undergo surgical resection and are staged with cancer that has spread to the pelvic peritoneum (stage II) and beyond (stages III and IV). The role of surgery for patients with stage IV disease is unclear, but in most instances, the bulk of the disease is intra-abdominal, and surgical procedures similar to those used in the management of patients with stage II and III disease are applied.

Surgery has historically been done by open laparotomy performed by gynecologic oncology surgeons, and has included hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, omentectomy, and debulking of peritoneal implants (often including resection of the bowel or adjacent organs as needed) to reduce tumor to microscopic, if it can safely be performed.

The volume of disease left at the completion of the primary surgical procedure in GOG studies has been related to patient survival.[2-5] A literature review showed that patients with optimal cytoreduction had a median survival of 39 months compared with survival of only 17 months in patients with suboptimal residual disease.[2][Level of evidence C1]

However, in an analysis of 2,655 of the 4,312 patients enrolled in the largest GOG study (GOG-0182 [NCT00011986]), only cytoreduction to nonvisible disease that is R0 (i.e., complete surgical resection) had an independent effect on survival. For more information, see the Surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy section.[6] The GOG had conducted separate trials to establish a role for intraperitoneal (IP) therapy for women whose disease has been optimally cytoreduced (defined as ≤1 cm residuum) and for those who had suboptimal cytoreductions (>1 cm residuum). For more information, see the Surgery before or after platinum-based chemotherapy and/or additional consolidation therapy section.

Suboptimally debulked stage III and stage IV patients have inferior 5-year survival rates, but the gap has narrowed in trials that included taxanes and other drugs added to platinums.[7] By contrast, optimally debulked stage III patients treated with a combination of intravenous (IV) taxane and IP platinum plus taxane achieved a median survival of 66 months in a GOG trial.[8][Level of evidence A1]

Surgery followed by platinum-based chemotherapy

Platinum agents, such as cisplatin or its less-toxic second-generation analog, carboplatin, given either alone or in combination with other drugs, are the foundation of chemotherapy regimens used. Trials by various cooperative groups (conducted from 1999 to 2010) addressed issues of optimal dose intensity [9-11] for both cisplatin and carboplatin,[12] schedule,[13] and the equivalent results obtained with either of these platinum drugs, usually in combination with cyclophosphamide.[14]

With the introduction of the taxane paclitaxel, two trials confirmed the superiority of cisplatin combined with paclitaxel when compared with the previous standard treatment of cisplatin plus cyclophosphamide.[15,16] However, two trials that compared single-agent paclitaxel with either cisplatin or carboplatin (ICON3 and GOG-132) failed to confirm such superiority in all outcome parameters (i.e., response, time-to-progression, and survival) (see Table 7 for a list of these studies).

Based on the evidence, the initial standard treatment for patients with ovarian cancer is the combination of cisplatin or carboplatin with paclitaxel (defined as induction chemotherapy).

Evidence (combination of cisplatin or carboplatin with paclitaxel):

- GOG-132 was widely regarded as showing that sequential treatment with cisplatin and paclitaxel was equivalent to the combination of cisplatin-plus-paclitaxel; however, many patients crossed over before disease progression. Moreover, the cisplatin-only arm was more toxic than the combination of cisplatin (75 mg/m2) and paclitaxel because it used a 100 mg/m2 cisplatin dose per cycle.[17]

- The Medical Research Council study (MRC-ICON3) compared carboplatin monotherapy with the combination of carboplatin and paclitaxel. While MRC-ICON3 had fewer early crossovers than GOG-132, it yielded similar outcomes for carboplatin monotherapy, including OS (albeit with less toxicity) compared with the combination treatment.[18]

Since the adoption of the standard combination of platinum plus taxane nearly worldwide, clinical trials have demonstrated the following:

- Noninferiority of carboplatin plus paclitaxel versus cisplatin plus paclitaxel.[15,16,19]

- Noninferiority of carboplatin plus paclitaxel versus carboplatin plus docetaxel.[20]

- No advantage but increased toxic effects of adding epirubicin to the carboplatin plus paclitaxel doublet.[21]

- Noninferiority of carboplatin plus paclitaxel versus sequential carboplatin-containing doublets with either gemcitabine or topotecan; or, triplets with the addition of gemcitabine or pegylated liposomal doxorubicin to the reference doublet as shown below:[22,23]

- From 2001 to 2004, 4,312 women with stage III or stage IV ovarian epithelial cancer, FTC, or PPC participating in the GOG-0182 trial were randomly assigned to four different experimental arms or to a reference treatment consisting of carboplatin (area under the curve [AUC], 6) and paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) every 3 weeks for eight cycles.[22] Stratification factors were residual-disease status and the intention to perform interval debulking surgery.

- None of the experimental regimens was inferior.

- Lethal events attributable to treatment occurred in less than 1% of patients without clustering to any one regimen.

- With a median follow-up of 3.7 years, the adjusted relative risk of death ranged from 0.952 to 1.114, with the control arm achieving a PFS of 16.0 months and a median OS of 44.1 months.

Moreover, for the stage III patients who made up 84% to 87% of patients, PFS differences were only noted if surgery achieved R0 resections:[22]

- PFS in patients with residuum larger than 1 cm was 13 months, and OS was 33 months.

- With residuum 1 cm or smaller, PFS was 16 months, and OS was 40 months.

- With R0 resection (e.g., no residuum or microscopic residuum only), PFS was 29 months, and OS was 68 months.

- From 2001 to 2004, 4,312 women with stage III or stage IV ovarian epithelial cancer, FTC, or PPC participating in the GOG-0182 trial were randomly assigned to four different experimental arms or to a reference treatment consisting of carboplatin (area under the curve [AUC], 6) and paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) every 3 weeks for eight cycles.[22] Stratification factors were residual-disease status and the intention to perform interval debulking surgery.

In gynecologic cancer, as opposed to breast cancer, weekly paclitaxel was not explored in phase III trials before 2004. The positive results from the Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group (JGOG) 3016 study subsequently led to early adoption of divided-dose paclitaxel as the standard treatment, but with only partial confirmation of its superior results.

Evidence (dose-dense [weekly] treatment schedule):

- A JGOG trial (JGOG-3016 [NCT00226915]) accrued 637 patients and randomly assigned them to six to nine cycles of weekly (dose-dense) paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) or to the standard every-21-day schedule of paclitaxel at 180 mg/m2. Both regimens were given with carboplatin (AUC, 6) in every-3-week cycles. The primary study end point was PFS with a goal of detecting a PFS increase from 16 months to 21 months in patients receiving the weekly paclitaxel-based regimen.[24,25] Although more toxic, the weekly paclitaxel regimen did not adversely affect quality of life when compared with the intermittent schedule.[26][Level of evidence B1]

Other than ethnicity, this trial population may have differed from GOG and other studies in that patients were younger (average age, 57 years). Twenty percent of patients had stage II disease and 33% of patients had histologies other than high-grade serous or endometrioid cancer. Also, 11% of patients were entered while receiving neoadjuvant treatment, which was an all-inclusive way of assessing treatments other than chemotherapy in first-line settings. The JGOG-3016 study results demonstrated the following results:

- At the 1.5-year follow-up after cessation of treatment, patients who received the weekly regimen had a median PFS of 28.0 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 22.3–35.4), and patients who received the intermittent regimen had a median PFS of 17.2 months (range, 15.7–21.1; hazard ratio [HR], 0.71), favoring the weekly regimen (P = .0015).

- A 2013 update revealed an increase in median survival for patients who received the weekly regimen (median OS, 8.3 years vs. 5.1 years; P = .040); the intermittent regimen results are also noteworthy relative to other clinical trials of weekly dosing schedules.

- In a phase III trial (MITO-7 [NCT00660842]), the outcomes of 406 patients assigned to weekly paclitaxel (60 mg/m2) administered with weekly carboplatin (AUC, 2) were compared with those of 404 patients receiving the conventional every-3-week regimen of paclitaxel and carboplatin.[27][Level of evidence A1]

- The results failed to confirm the superiority of this weekly schedule (18.3 months PFS for the weekly arm vs. 17.3 months PFS for the standard arm [HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.80–1.16]).

- The treatments did not differ in toxic effects. A decrease in quality of life (assessed by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Ovarian Trial Outcome Index questionnaire) was not seen in the weekly arm compared with the every-3-week arm.

- GOG-0262 (NCT01167712) is a phase III study that compared weekly paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) to every-3-week dosing (175 mg/m2), both with the conventional every-3-week carboplatin (AUC, 6) regimen.[28][Level of evidence B1] An option to give bevacizumab every 3 weeks beginning with cycle two and continuing until cycle six and followed by bevacizumab alone for 1 year, as in GOG-0218, was included for both arms. This option was applied in about 84% of all patients.

- Overall, the weekly paclitaxel regimen failed to prolong PFS compared with the every-3-week regimen (14.7 months vs. 14.0 months), with an HR for progression or death of 0.89 (95% CI, 0.74–1.06).

- However, among patients not receiving bevacizumab, the weekly paclitaxel arm had significantly prolonged PFS (14.2 months vs. 10.3 months), with an HR of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.40–0.95; P = .03)

- The weekly paclitaxel regimen had a higher rate of grade 3 or 4 anemia (36% vs. 16%) and grade 2 to 4 sensory neuropathy (26% vs. 18%).

- The phase III ICON8 (NCT01654146) trial compared weekly paclitaxel with every-3-week dosing, with another arm that compared weekly paclitaxel with weekly carboplatin (AUC, 2 ˣ 6 cycles).[29]

- This large study did not demonstrate any significant differences between the arms.

- A separate quality-of-life study found no difference in global quality of life among the three groups at a 9-month cross-sectional analysis, although the weekly paclitaxel schedules scored significantly lower in longitudinal analyses.[30]

While weekly paclitaxel dosing remains an option for the appropriate patient, several large trials have not been able to replicate the superiority of this treatment, and this regimen is now used less often.[31]

| Trial | Treatment Regimens | No. of Patients | Progression-Free Survival (mo) | Overall Survival (mo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC = area under the curve; EORTC = European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; Est = estimated; GOG = Gynecologic Oncology Group; ICON = International Collaboration on Ovarian Neoplasms; JGOG = Japanese Gynecologic Oncology Group; MITO = Multicentre Italian Trials in Ovarian cancer; MRC = Medical Research Council; No. = number; NR = not reported. | ||||

| aControl arms are bolded. | ||||

| bStatistically inferior result (P < .001–< .05). | ||||

| cOptimally debulked only. | ||||

| dEvery 3 weeks for six cycles unless specified. | ||||

| eJGOG-3016 included stage II patients. | ||||

| fEstimated from the curve. | ||||

| GOG-111 (1990–1992)a [32] | Paclitaxel (135 mg/m2, 24 h) and cisplatin (75 mg/m2) | 184 | 18 | 38 |

| Cyclophosphamide (750 mg/m2) and cisplatin (75 mg/m2) | 202 | 13b | 24b | |

| EORTC-55931 | Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2, 3 h) and cisplatin (75 mg/m2) | 162 | 15.5 | 35.6 |

| Cyclophosphamide (750 mg/m2) and cisplatin (75 mg/m2) | 161 | 11.5b | 25.8b | |

| GOG-132 (1992–1994) | Paclitaxel (135 mg/m2, 24 h) and cisplatin (75 mg/m2) | 201 | 14.2 | 26.6 |

| Cisplatin (100 mg/m2) | 200 | 16.4 | 30.2 | |

| Paclitaxel (200 mg/m2, 24 h) | 213 | 11.2b | 26 | |

| MRC-ICON3 [18] | Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2, 3 h) and carboplatin (AUC, 6) | 478 | 17.3 | 36.1 |

| Carboplatin (AUC, 6) | 943 | 16.1 | 35.4 | |

| Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2, 3 h) and carboplatin (AUC, 6) | 232 | 17 | 40 | |

| Cyclophosphamide (500 mg/m2) and doxorubicin (50 mg/m2) and cisplatin (50 mg/m2) | 421 | 17 | 40 | |

| GOG-158 (1995–1998)c | Paclitaxel (135 mg/m2, 24 h) and cisplatin (75 mg/m2)d | 425 | 14.5 | 48 |

| Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2, 3 h) and carboplatin (AUC, 6) | 415 | 15.5 | 52 | |

| JGOG-3016 (2002–2004)e | Paclitaxel (180 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC, 6)d | 319 | 17.5 | 62.2 |

| Paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC, 6) | 312 | 28.5 | 100.5 | |

| MITO-7 [27,33] | Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC, 6)d | 404 | 17.3 | NR |

| Paclitaxel (60 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC, 6) | 406 | 18.3 | NR | |

| GOG-0262 [28] | Paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC, 6) plus optional bevacizumab cycles 2–6, and every 3 wk until progression | 346 | 14.7 | Est 42 |

| Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC, 6) (× 6 cycles) plus optional bevacizumab cycles 2–6, and every 3 wk until progression | 346 | 14.0 | Est 42 | |

| GOG-218 | Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC, 6) (× 6 cycles) and placebo cycles 2–22 | 625 | 10.3 | 39.3 |

| Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC, 6) (× 6 cycles) and bevacizumab cycles 2–6, and placebo cycles 7–22 | 625 | 11.2 | 38.7 | |

| Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC, 6) (× 6 cycles) and bevacizumab cycles 2–22 | 623 | 14.1 | 39.7 | |

| ICON7 [34] | Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC, 5 or 6) and bevacizumab (7.5 mg/kg) (× 6 cycles) and bevacizumab alone cycles 7–18 | 764 | 19.0 | 45.5 |

| Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC, 5 or 6) (× 6 cycles) | 764 | 17.3 | 44.6 | |

| ICON8 [29,31] | Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) and carboplatin (AUC, 5 or 6) (× 6 cycles) | 522 | 17.5 | 47.4f |

| Paclitaxel (80 mg/m2 weekly) and carboplatin (AUC, 5 or 4) (× 6 cycles) | 523 | 20.1 | 54.8f | |

| Paclitaxel (80 mg/m2 weekly) and carboplatin (AUC, 2 weekly) (× 6 cycles) | 521 | 20.1 | 53.4f | |

Surgery before or after platinum-based chemotherapy and/or additional consolidation therapy

The pharmacological basis for the delivery of anticancer drugs by the IP route was established in the late 1970s and early 1980s. When several drugs were studied, mostly in the setting of measurable residual disease at reassessment after patients had received their initial chemotherapy, cisplatin alone and in combination received the most attention. Favorable outcomes from IP cisplatin were most often seen when tumors had shown responsiveness to platinum therapy and with small-volume tumors (usually defined as tumors <1 cm).[35]

In the 1990s, randomized trials were conducted to evaluate whether the IP route would prove superior to the IV route. IP cisplatin was the common denominator of these randomized trials.

Evidence (surgery followed by IP chemotherapy):

- The use of IP cisplatin as part of the initial approach in patients with stage III optimally debulked ovarian cancer is supported principally by the results of three randomized clinical trials (SWOG-8501, GOG-0114, and GOG-0172 [NCT00003322]).[8,36,37] These studies tested the role of IP drugs (IP cisplatin in all three studies and IP paclitaxel in the last study) against the standard IV regimen.

- In the three studies, superior PFS and OS favoring the IP arm were documented.

Specifically, the most recent study, GOG-0172, demonstrated the following results:[8][Level of evidence A1]

- A median survival of 66 months for patients on the IP arm versus 50 months for patients who received IV administration of cisplatin and paclitaxel (P = .03).

- Toxic effects were greater in the IP arm because of the cisplatin dose per cycle (100 mg/m2); sensory neuropathy resulted from the additional IP chemotherapy and from the systemic administration of paclitaxel.

- The rate of completion of six cycles of treatment was also less frequent in the IP arm (42% vs. 83%) because of the toxic effects and catheter-related problems.

An updated combined analysis of GOG-0114 and GOG-0172 included 876 patients with a median follow-up of 10.7 years and reported the following results:[38]

- Median survival with IP therapy was 61.8 months (95% CI, 55.5–69.5) compared with 51.4 months (95% CI, 46.0–58.2) for IV therapy.

- IP therapy was associated with a 23% decreased risk of death (adjusted hazard ratio [AHR], 0.77; 95% CI, 0.65–0.90; P = .002).

- IP therapy improved the survival of patients with gross residual (≤1 cm) disease (AHR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.62–0.92; P = .006).

- Risk of death decreased by 12% for each cycle of IP chemotherapy completed (AHR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.83–0.94; P < .001).

- Factors associated with poorer survival included clear and mucinous versus serous histology (AHR, 2.79; 95% CI, 1.83–4.24; P < .001), gross residual versus no visible disease (AHR, 1.89; 95% CI, 1.48–2.43; P < .001), and fewer versus more cycles of IP chemotherapy (AHR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.83–0.94; P < .001).