Esophageal Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version

General Information About Esophageal Cancer

Two histological types account for most malignant esophageal neoplasms: adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Adenocarcinomas typically start in the lower esophagus, and squamous cell carcinoma can develop throughout the esophagus. The epidemiology of these types varies markedly.

Incidence and Mortality

Estimated new cases and deaths from esophageal cancer in the United States in 2025:[1]

- New cases: 22,070.

- Deaths: 16,250.

The incidence of esophageal cancer has risen in recent decades, coinciding with a shift in histological type and primary tumor location. Worldwide, squamous cell carcinoma is the predominant histology, and was historically more prevalent in the United States. However, the incidence of adenocarcinoma has risen dramatically in the last few decades and is now more prevalent than squamous cell carcinoma in the United States and western Europe.[2-4] The incidence of adenocarcinoma has increased most notably among White men.[5] In the United States, the median age of patients who present with esophageal cancer is 68 years.[6] Most adenocarcinomas are located in the distal esophagus. The cause of the rising incidence and demographic alterations is unknown.

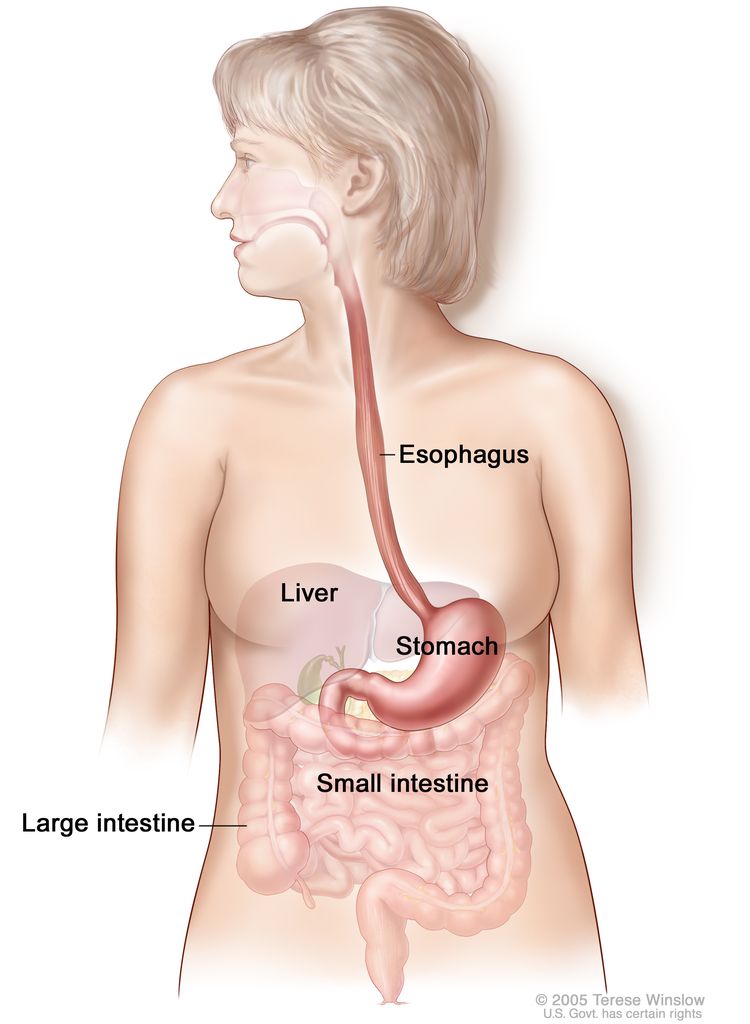

Anatomy

The esophagus serves as a conduit to the gastrointestinal tract for food. The esophagus extends from the larynx to the stomach and lies in the posterior mediastinum within the thorax near the lung pleura, peritoneum, pericardium, and diaphragm. As it travels into the abdominal cavity, the esophagus makes an abrupt turn and enters the stomach. The most muscular segment of the gastrointestinal system, the esophagus is composed of inner circular and outer longitudinal muscle layers. The upper and lower esophagus are controlled by the sphincter function of the cricopharyngeus muscle and gastroesophageal sphincter, respectively. The esophagus has a rich network of lymphatic channels concentrated in the lamina propria and submucosa, which drains longitudinally along the submucosa.

Tumors of the esophagus are conventionally described in terms of distance of the upper border of the tumor to the incisors. When measured from the incisors via endoscopy, the esophagus extends approximately 30 cm to 40 cm. The esophagus is divided into four main segments:

- Cervical esophagus (~15–20 cm from the incisors).

- Upper thoracic esophagus (~20–25 cm from the incisors).

- Middle thoracic esophagus (~25–30 cm from the incisors).

- Lower thoracic esophagus and gastroesophageal junction (~30–40 cm from the incisors).

Risk Factors

Risk factors for squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus include:

- Tobacco use.

- Alcohol use.

Risk factors associated with esophageal adenocarcinoma are less clear.[3] Barrett esophagus is an exception, and its presence is associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Chronic reflux is considered the predominant cause of Barrett metaplasia. The results of a population-based, case-controlled study from Sweden strongly suggest that symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux is a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. The frequency, severity, and duration of reflux symptoms were positively correlated with increased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma.[7] For more information, see Esophageal Cancer Prevention.

Prognostic Factors

Favorable prognostic factors include:

- Early-stage disease.

- Complete resection.

Patients with severe dysplasia in distal esophageal Barrett mucosa often have in situ or invasive cancer within the dysplastic area. After resection, these patients usually have excellent prognoses.[8]

In most cases, esophageal cancer is a treatable disease, but it is rarely curable. The 5-year relative survival rate is 21.6%. Patients with early-stage disease have a better chance of survival; 18.2% of patients are diagnosed at the local stage and have a 5-year relative survival rate of 48.1%.[6]

References

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2025. American Cancer Society, 2025. Available online. Last accessed January 16, 2025.

- Brown LM, Devesa SS, Chow WH: Incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus among white Americans by sex, stage, and age. J Natl Cancer Inst 100 (16): 1184-7, 2008. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Blot WJ, McLaughlin JK: The changing epidemiology of esophageal cancer. Semin Oncol 26 (5 Suppl 15): 2-8, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schmassmann A, Oldendorf MG, Gebbers JO: Changing incidence of gastric and oesophageal cancer subtypes in central Switzerland between 1982 and 2007. Eur J Epidemiol 24 (10): 603-9, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Kubo A, Corley DA: Marked multi-ethnic variation of esophageal and gastric cardia carcinomas within the United States. Am J Gastroenterol 99 (4): 582-8, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- National Cancer Institute: SEER Cancer Stat Facts: Esophageal Cancer. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute. Available online. Last accessed February 7, 2025.

- Lagergren J, Bergström R, Lindgren A, et al.: Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 340 (11): 825-31, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Reed MF, Tolis G, Edil BH, et al.: Surgical treatment of esophageal high-grade dysplasia. Ann Thorac Surg 79 (4): 1110-5; discussion 1110-5, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

Cellular Classification of Esophageal Cancer

Adenocarcinomas, typically arising in Barrett esophagus, account for at least 50% of malignant lesions, and the incidence of this histology appears to be rising. Barrett esophagus contains glandular epithelium cephalad to the esophagogastric junction.

Three different types of glandular epithelium can be seen:

- Metaplastic columnar epithelium.

- Metaplastic parietal cell glandular epithelium within the esophageal wall.

- Metaplastic intestinal epithelium with typical goblet cells. Dysplasia is particularly likely to develop in the intestinal-type mucosa.

Approximately 30% of esophageal cancers in the United States are squamous cell carcinomas.[1]

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors can occur in the esophagus and are usually benign. For more information, see Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors Treatment.

References

- Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al.: SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR) 1975-2017. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute, 2020. Available online. Last accessed February 7, 2025.

Stage Information for Esophageal Cancer

One of the major difficulties in allocating and comparing treatment modalities for patients with esophageal cancer is the lack of precise preoperative staging. The stage determines whether the intent of the therapeutic approach will be curative or palliative.

Staging Evaluation

Standard noninvasive staging modalities include:

- Endoscopic ultrasonography.

- Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest and abdomen.

- Positron emission tomography (PET)–CT scan.

The overall tumor depth staging accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography is 85% to 90%, compared with 50% to 80% for CT. The accuracy of regional nodal staging is 70% to 80% for endoscopic ultrasonography and 50% to 70% for CT.[1,2]

One retrospective series reported 93% sensitivity and 100% specificity of regional nodal staging with endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA). Endoscopic ultrasound-guided FNA for lymph node staging is under prospective evaluation.[3]

Thoracoscopy and laparoscopy have been used in esophageal cancer staging at some surgical centers.[4-6] An intergroup trial reported an increase in positive lymph node detection to 56% of 107 evaluable patients with the use of thoracoscopy/laparoscopy, from 41% (with the use of noninvasive staging tests, e.g., CT, magnetic resonance imaging, and endoscopic ultrasound), with no major complications or deaths.[7]

Noninvasive PET scan using the radiolabeled glucose analog fluorine F 18-fludeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) for preoperative staging of esophageal cancer is more sensitive than a CT scan or endoscopic ultrasound in detection of distant metastases. A recent study of 262 patients with potentially resectable esophageal cancer demonstrated the utility of 18F-FDG PET in identifying confirmed distant metastatic disease in at least 4.8% of patients after standard evaluation.[8-12]

AJCC Staging System

The AJCC has designated staging by TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) classification to define cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction.[13] Tumors located in the gastric cardia within 5 cm of the gastroesophageal junction with extension into the esophagus or the gastroesophageal junction are classified as esophageal cancer. Tumors with the epicenter of the tumor located in the gastric cardia beyond 5 cm of the gastroesophageal junction or without extension into the esophagus are classified as gastric cancer.[13] For more information, see the Stage Information for Gastric Cancer section in Gastric Cancer Treatment.

The classification of involved abdominal lymph nodes as M1 disease is controversial. The presence of positive abdominal lymph nodes does not appear to have a prognosis as grave as that for metastases to distant organs.[14] Patients with regional and/or celiac axis lymphadenopathy should not necessarily be considered to have unresectable disease caused by metastases. Complete resection of the primary tumor and appropriate lymphadenectomy is attempted when possible.

| T Category/Criteria | N Category/Criteria | M Category/Criteria | G Definition | L Category/Criteriab | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph nodes; M = distant metastasis; G = grade; L = location. | |||||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Esophageal and esophagogastric junction. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 185–202. | |||||

| bLocation is defined by the position of the epicenter of the tumor in the esophagus. | |||||

| TX = Tumor cannot be assessed. | NX = Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed. | M0 = No distant metastasis. | GX = Grade cannot be assessed. | X = Location unknown. | |

| T0 = No evidence of primary tumor. | N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | M1 = Distant metastasis. | G1 = Well differentiated. | Upper = Cervical esophagus to lower border of azygos vein. | |

| Tis = High-grade dysplasia, defined as malignant cells confined to the epithelium by the basement membrane. | N1 = Metastasis in one or two regional lymph nodes. | G2 = Moderately differentiated. | Middle = Lower border of azygos vein to lower border of inferior pulmonary vein. | ||

| G3 = Poorly differentiated, undifferentiated. | Lower = Lower border of inferior pulmonary vein to stomach, including gastroesophageal junction. | ||||

| T1 = Tumor invades the lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, or submucosa. | N2 = Metastasis in three to six regional lymph nodes. | ||||

| N3 = Metastasis in seven or more regional lymph nodes. | |||||

| T1a = Tumor invades the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae. | |||||

| T1b = Tumor invades the submucosa. | |||||

| T2 = Tumor invades the muscularis propria. | |||||

| T3 = Tumor invades adventitia. | |||||

| T4 = Tumor invades adjacent structures. | |||||

| T4a = Tumor invades the pleura, pericardium, azygos vein, diaphragm, or peritoneum. | |||||

| T4b = Tumor invades other adjacent structures, such as the aorta, vertebral body, or airway. | |||||

Staging for squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus

| Stage | TNM | Grade | Tumor Location | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph nodes; M = distant metastasis; G = grade; L = location; N/A = not applicable; p = pathological. | |||||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Esophageal and esophagogastric junction. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 185–202 | |||||

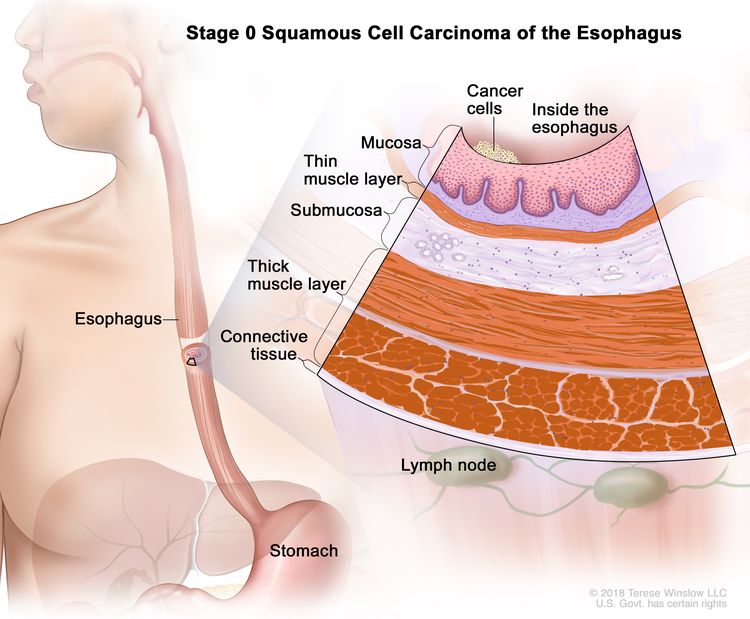

| 0 | Tis, N0, M0 | N/A | Any | Tis = High grade dysplasia, defined as malignant cells confined to the epithelium by the basement membrane. |

|

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| G1 = N/A. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

| Stage | TNM | Grade | Tumor Location | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph nodes; M = distant metastasis; G = grade; L = location; p = pathological. | |||||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Esophageal and esophagogastric junction. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 185–202. | |||||

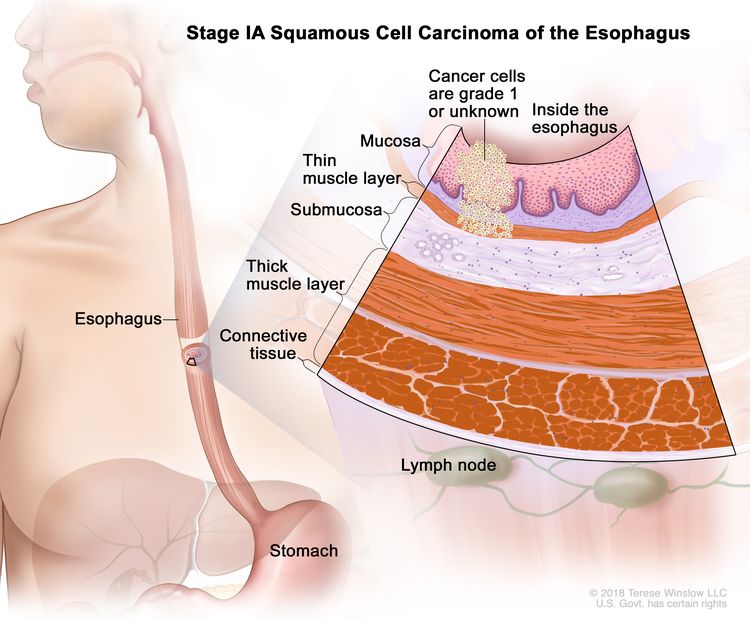

| IA | T1a, N0, M0 | G1 | Any | –T1a = Tumor invades the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae. |

|

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| G1 = Well differentiated. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

| T1a, N0, M0 | GX | Any | –T1a = Tumor invades the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae. | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| GX = Grade cannot be assessed. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

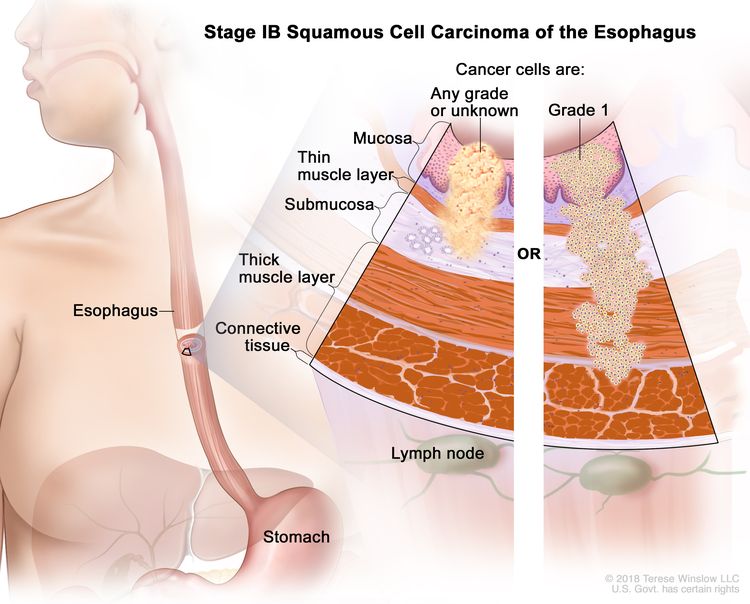

| IB | T1a, N0, M0 | G2–G3 | Any | –T1a = Tumor invades the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae. |

|

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| G2 = Moderately differentiated. | |||||

| G3 = Poorly differentiated, undifferentiated. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

| T1b, N0, M0 | G1–G3 | Any | –T1b = Tumor invades the submucosa. | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| G1 = Well differentiated. | |||||

| G2 = Moderately differentiated. | |||||

| G3 = Poorly differentiated, undifferentiated. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

| T1b, N0, M0 | GX | Any | –T1b = Tumor invades the submucosa. | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| GX = Grade cannot be assessed. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

| T2, N0, M0 | G1 | Any | T2 = Tumor invades the muscularis propria. | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| G1 = Well differentiated. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

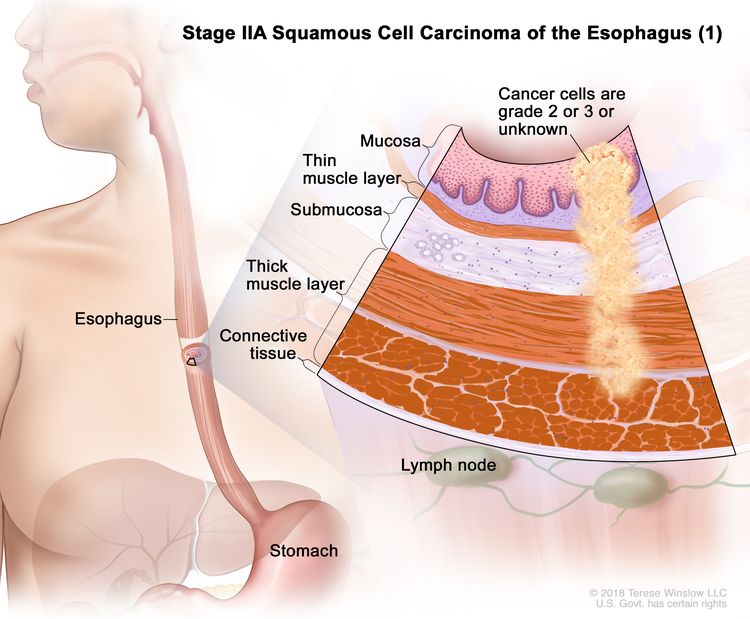

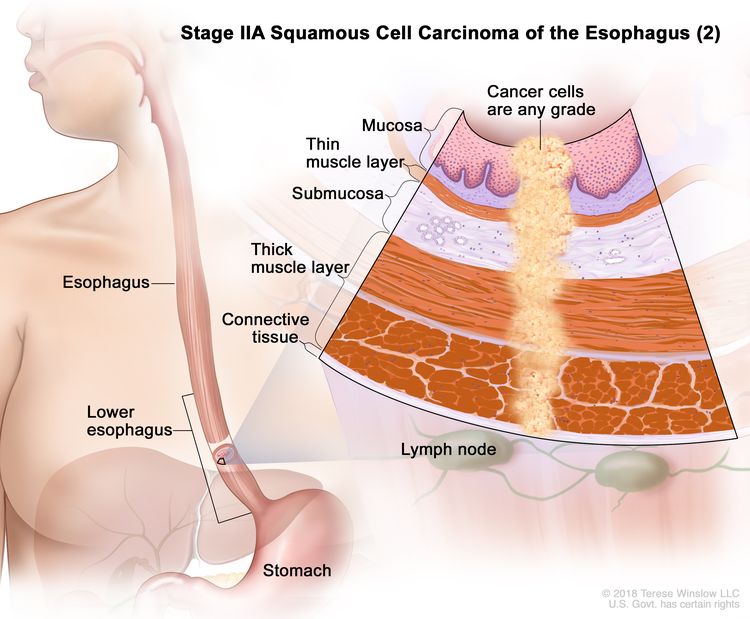

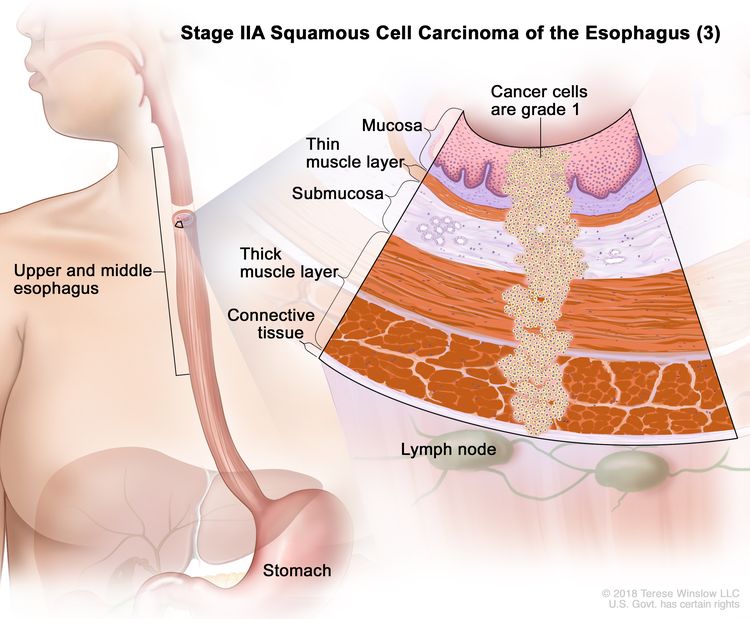

| Stage | TNM | Grade | Tumor Locationb | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph nodes; M = distant metastasis; G = grade; L = location; p = pathological. | |||||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Esophageal and esophagogastric junction. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 185–202. | |||||

| bLocation is defined by the position of the epicenter of the tumor in the esophagus. | |||||

| IIA | T2, N0, M0 | GX | Any | T2 = Tumor invades the muscularis propria. |

|

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| GX = Grade cannot be assessed. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

| T2, N0, M0 | G2–G3 | Any | T2 = Tumor invades the muscularis propria. | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| G2 = Moderately differentiated. | |||||

| G3 = Poorly differentiated, undifferentiated. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

| T3, N0, M0 | Any | Lower | T3 = Tumor invades adventitia. | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | |||||

| Lower = Lower border of inferior pulmonary vein to stomach, including gastroesophageal junction. | |||||

| T3, N0, M0 | G1 | Upper/middle | T3 = Tumor invades adventitia. | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| G1 = Well differentiated. | |||||

| Upper = Cervical esophagus to lower border of azygos vein. | |||||

| Middle = Lower border of azygos vein to lower border of inferior pulmonary vein. | |||||

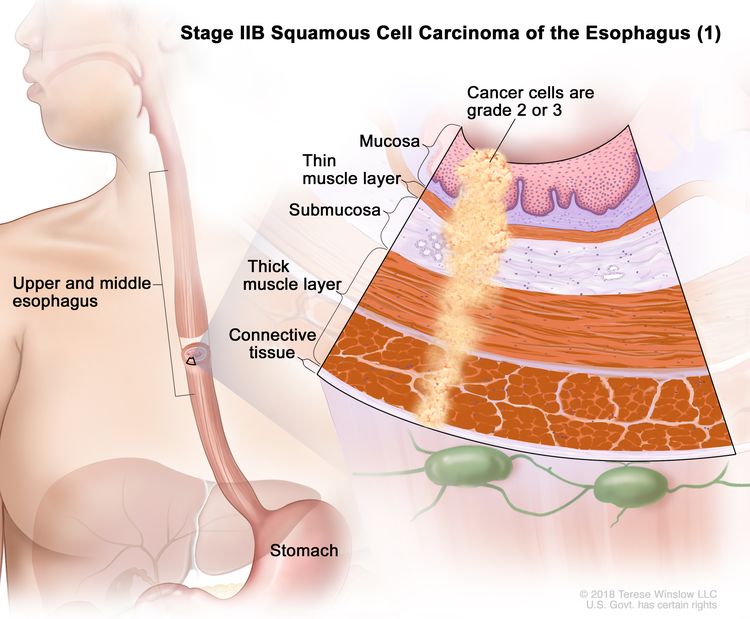

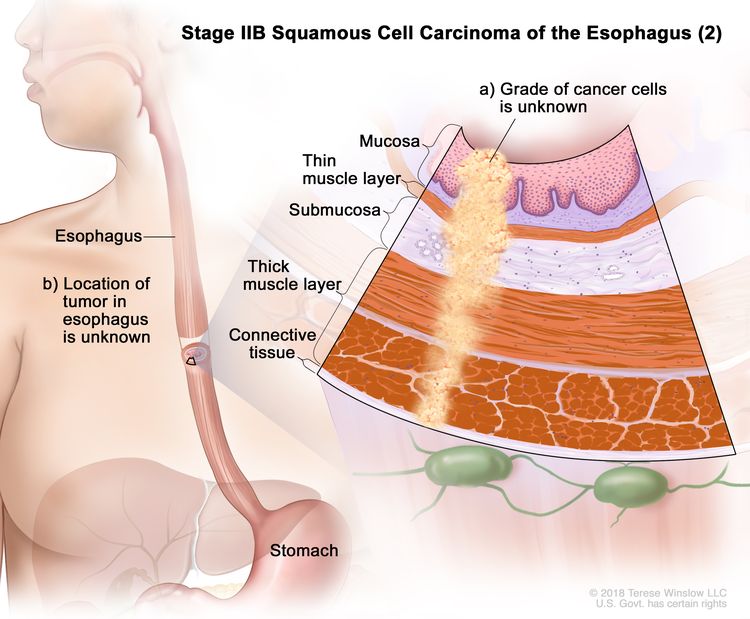

| IIB | T3, N0, M0 | G2–G3 | Upper/middle | T3 = Tumor invades adventitia. |

|

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| G2 = Moderately differentiated. | |||||

| G3 = Poorly differentiated, undifferentiated. | |||||

| Upper = Cervical esophagus to lower border of azygos vein. | |||||

| Middle = Lower border of azygos vein to lower border of inferior pulmonary vein. | |||||

| T3, N0, M0 | GX | Any | T3 = Tumor invades adventitia. | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| GX = Grade cannot be assessed. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

| T3, N0, M0 | Any | Location X | T3 = Tumor invades adventitia. | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | |||||

| Location X = Location unknown. | |||||

| T1, N1, M0 | Any | Any | T1 = Tumor invades the lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, or submucosa. | ||

| N1 = Metastasis in one or two regional lymph nodes. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

| Stage | TNM | Grade | Tumor Locationb | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph nodes; M = distant metastasis; G = grade; L = location; p = pathological. | |||||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Esophageal and esophagogastric junction. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 185–202. | |||||

| bLocation is defined by the position of the epicenter of the tumor in the esophagus. | |||||

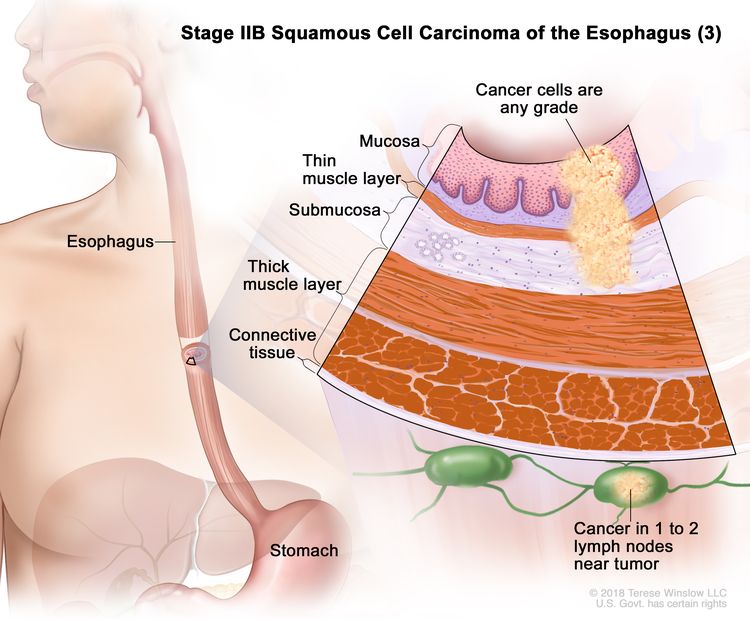

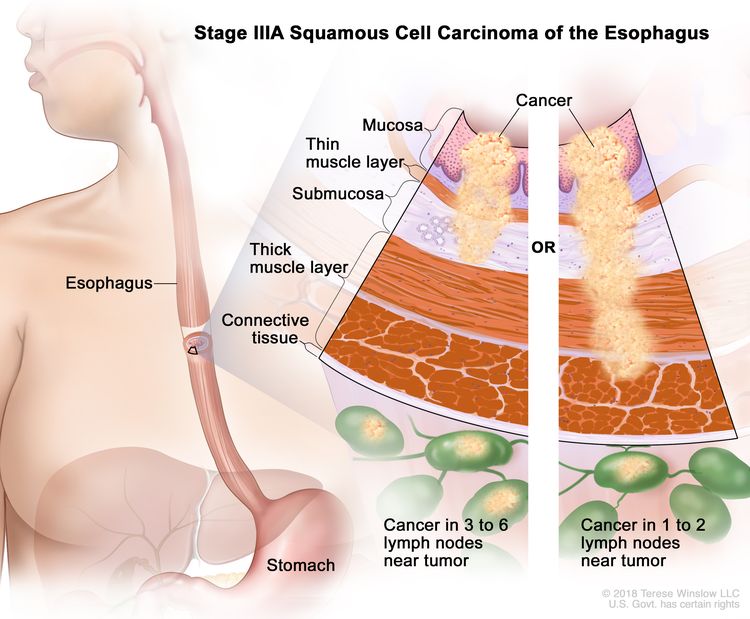

| IIIA | T1, N2, M0 | Any | Any | T1 = Tumor invades the lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, or submucosa. |

|

| –T1a = Tumor invades the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae. | |||||

| –T1b = Tumor invades the submucosa. | |||||

| N2 = Metastasis in three to six regional lymph nodes. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

| T2, N1, M0 | Any | Any | T2 = Tumor invades the muscularis propria. | ||

| N1 = Metastasis in one or two regional lymph nodes. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

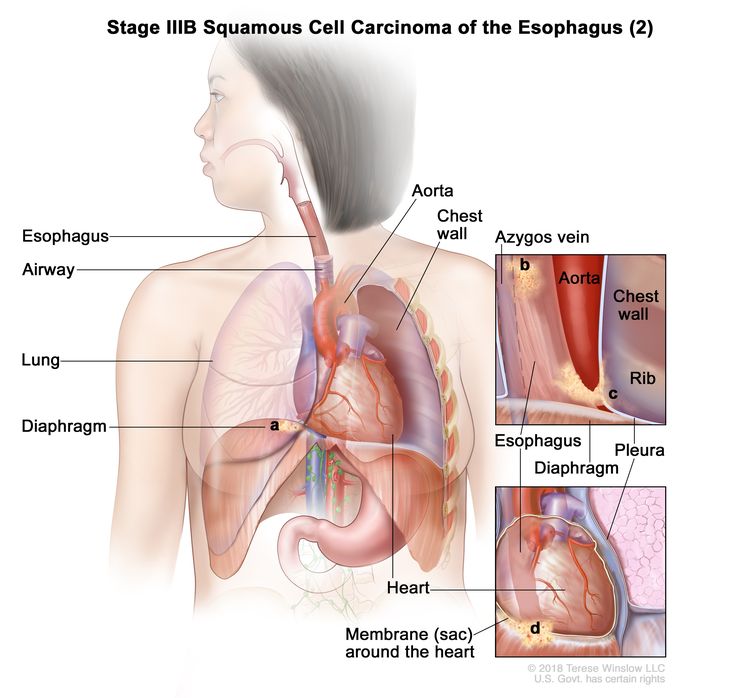

| IIIB | T2, N2, M0 | Any | Any | T2 = Tumor invades the muscularis propria. |

|

| N2 = Metastasis in three to six regional lymph nodes. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

| T3, N1–N2, M0 | Any | Any | T3 = Tumor invades adventitia. | ||

| N1 = Metastasis in one or two regional lymph nodes. | |||||

| N2 = Metastasis in three to six regional lymph nodes. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

| T4a, N0–1, M0 | Any | Any | –T4a = Tumor invades the pleura, pericardium, azygos vein, diaphragm, or peritoneum. |

|

|

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||||

| N1 = Metastasis in one or two regional lymph nodes. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

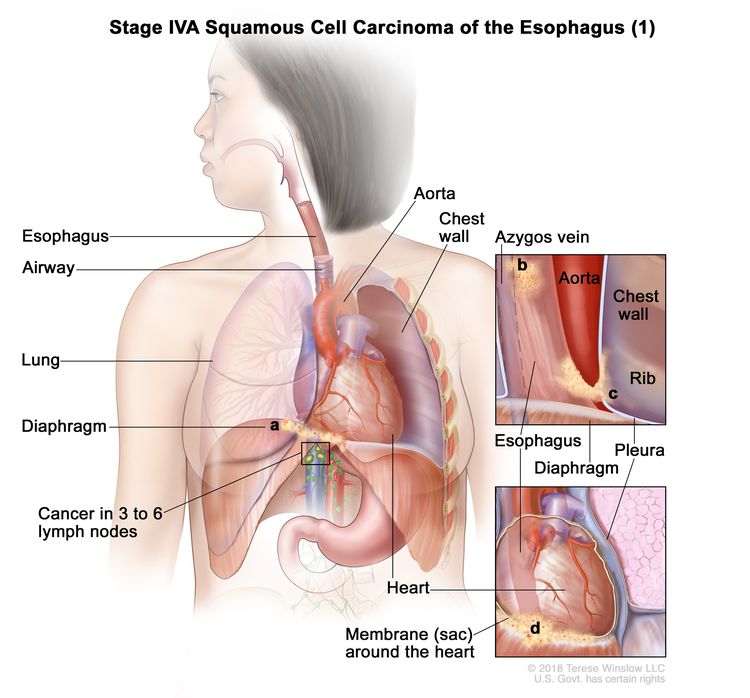

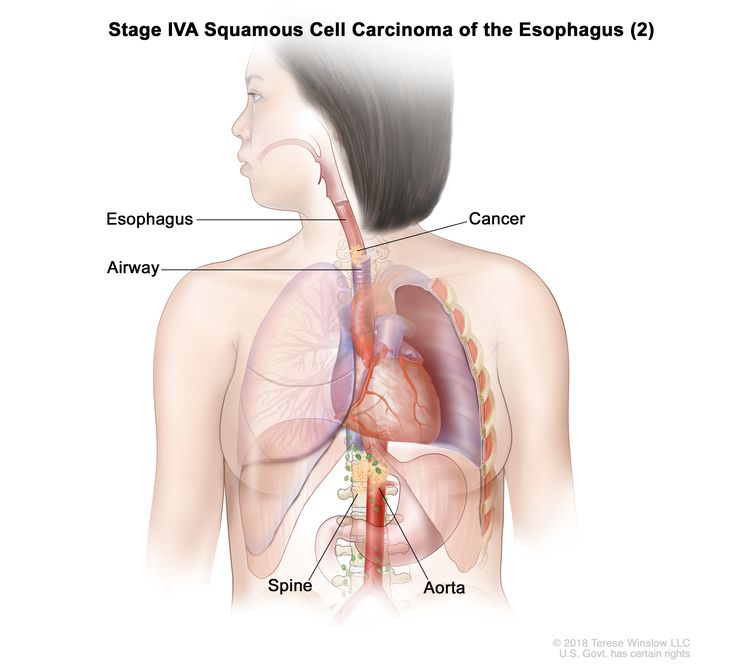

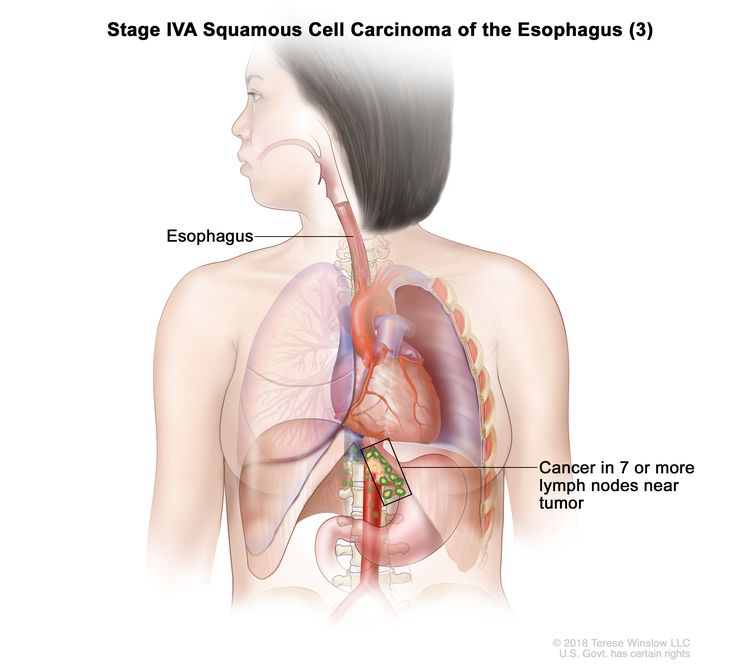

| Stage | TNM | Grade | Tumor Locationb | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph nodes; M = distant metastasis; G = grade; L = location; p = pathological. | |||||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Esophageal and esophagogastric junction. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 185–202. | |||||

| bLocation is defined by the position of the epicenter of the tumor in the esophagus. | |||||

| IVA | T4a, N2, M0 | Any | Any | –T4a = Tumor invades the pleura, pericardium, azygos vein, diaphragm, or peritoneum. |

|

| N2 = Metastasis in three to six regional lymph nodes. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

| T4b, N0–2, M0 | Any | Any | –T4b = Tumor invades other adjacent structures, such as the aorta, vertebral body, or airway. |

|

|

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||||

| N1 = Metastasis in one or two regional lymph nodes. | |||||

| N2 = Metastasis in three to six regional lymph nodes. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

| Any T, N3, M0 | Any | Any | Any T = See Table 1. |

|

|

| N3 = Metastasis in seven or more regional lymph nodes. | |||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | |||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

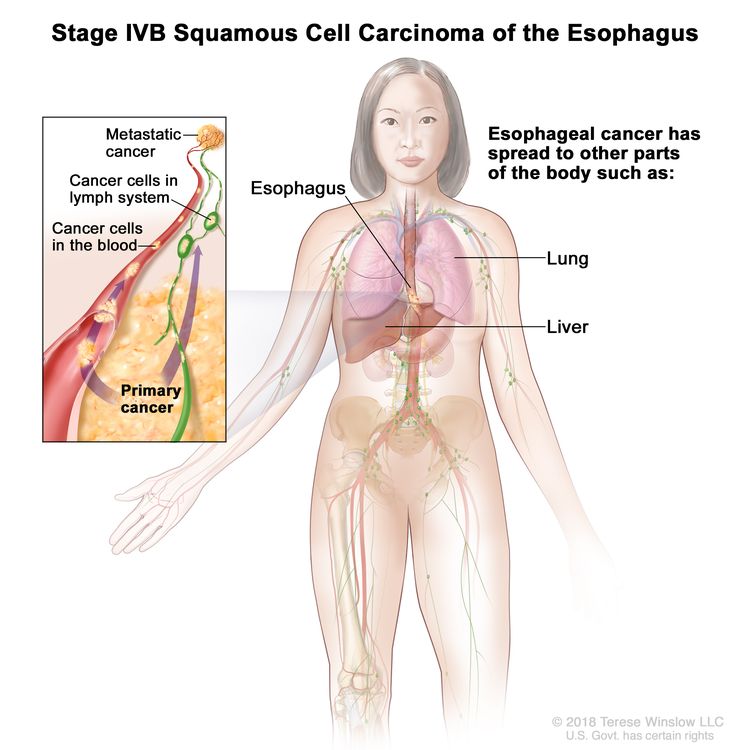

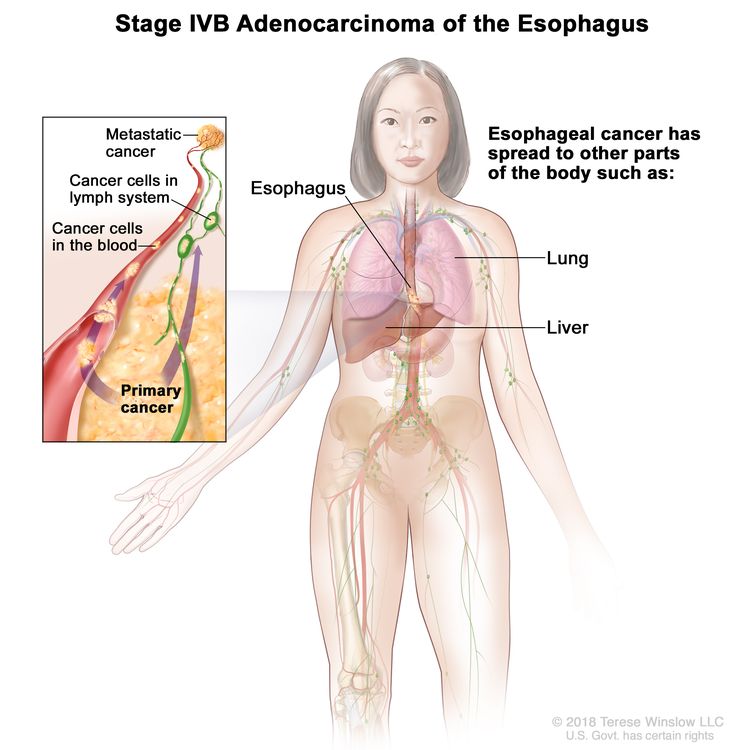

| IVB | Any T, Any N, M1 | Any | Any | Any T = See Table 1. |

|

| Any N = See Table 1. | |||||

| M1 = Distant metastasis. | |||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | |||||

| Any L = See Table 1. | |||||

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

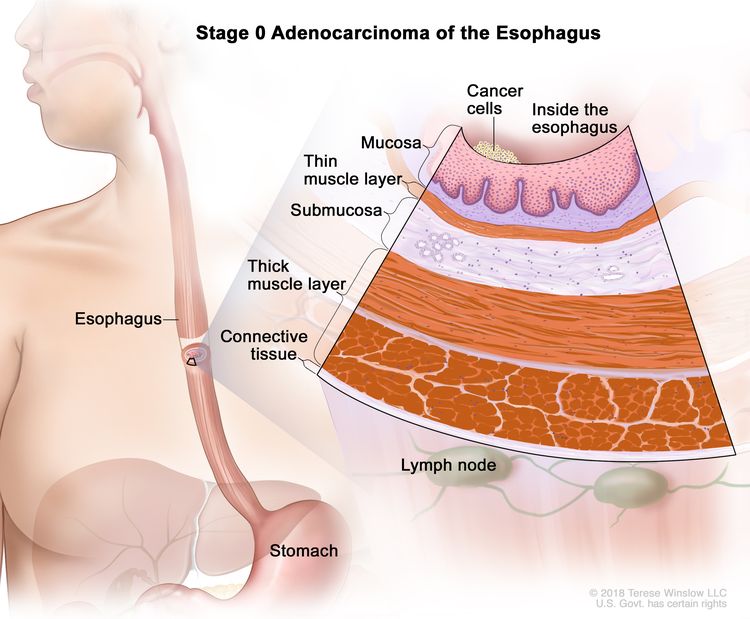

Staging for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus

| Stage | TNM | Grade | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph nodes; M = distant metastasis; G = grade; N/A = not applicable; p = pathological. | ||||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Esophageal and esophagogastric junction. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 185–202. | ||||

| 0 | Tis, N0, M0 | N/A | Tis = High-grade dysplasia, defined as malignant cells confined to the epithelium by the basement membrane. |

|

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

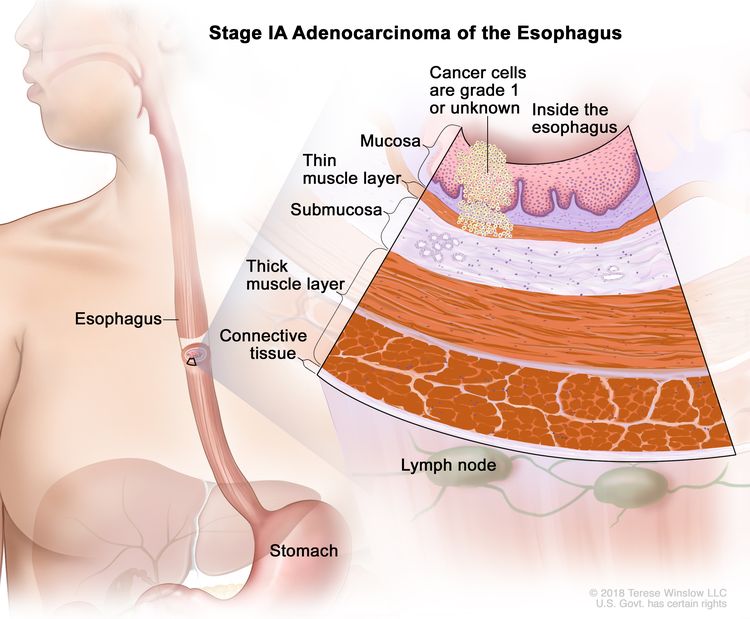

| Stage | TNM | Grade | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph nodes; M = distant metastasis; G = grade; p = pathological. | ||||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Esophageal and esophagogastric junction. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 185–202. | ||||

| IA | T1a, N0, M0 | G1 | –T1a = Tumor invades the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae. |

|

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| G1 = Well differentiated. | ||||

| T1a, N0, M0 | GX | –T1a = Tumor invades the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae. | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| GX = Grade cannot be assessed. | ||||

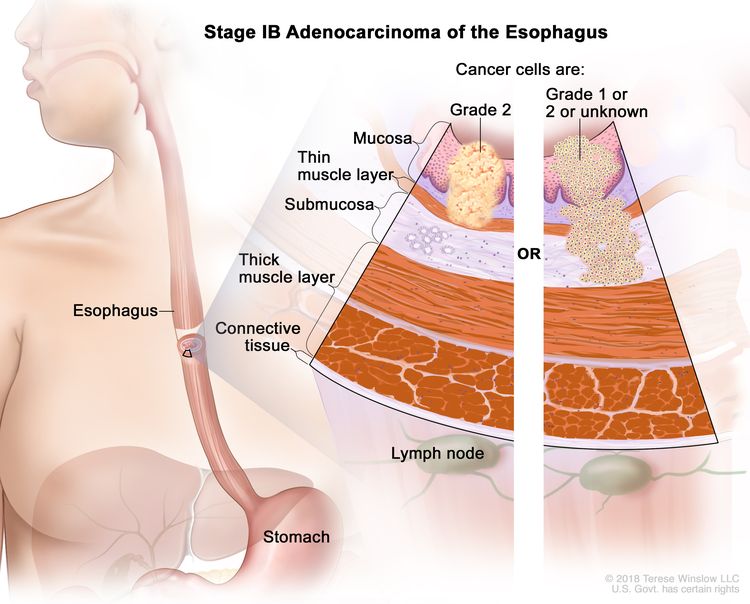

| IB | T1a, N0, M0 | G2 | –T1a = Tumor invades the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae. |

|

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| G2 = Moderately differentiated. | ||||

| T1b, N0, M0 | G1–2 | –T1b = Tumor invades the submucosa. | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| G1 = Well differentiated. | ||||

| G2 = Moderately differentiated. | ||||

| T1b, N0, M0 | GX | –T1b = Tumor invades the submucosa. | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| GX = Grade cannot be assessed. | ||||

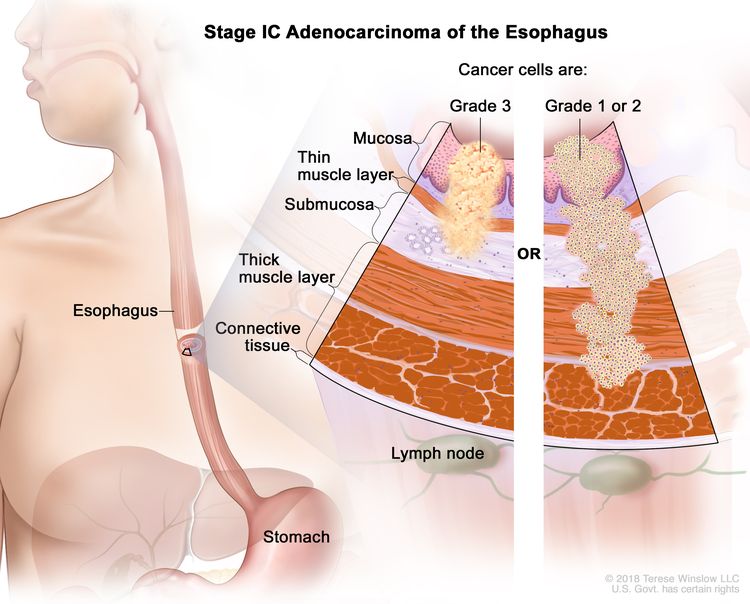

| IC | T1, N0, M0 | G3 | T1 = Tumor invades the lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, or submucosa. |

|

| –T1a = Tumor invades the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae. | ||||

| –T1b = Tumor invades the submucosa. | ||||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| G3 = Poorly differentiated, undifferentiated. | ||||

| T2, N0, M0 | G1–2 | T2 = Tumor invades the muscularis propria. | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| G1 = Well differentiated. | ||||

| G2 = Moderately differentiated. | ||||

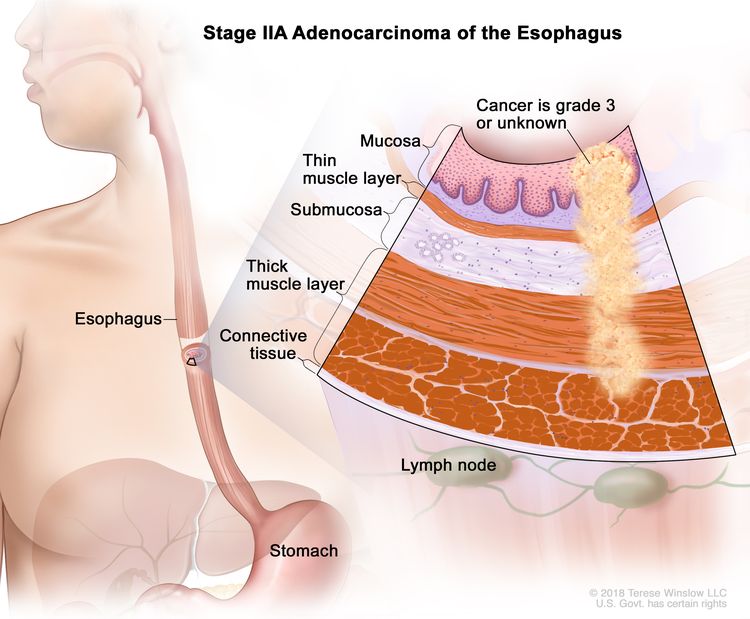

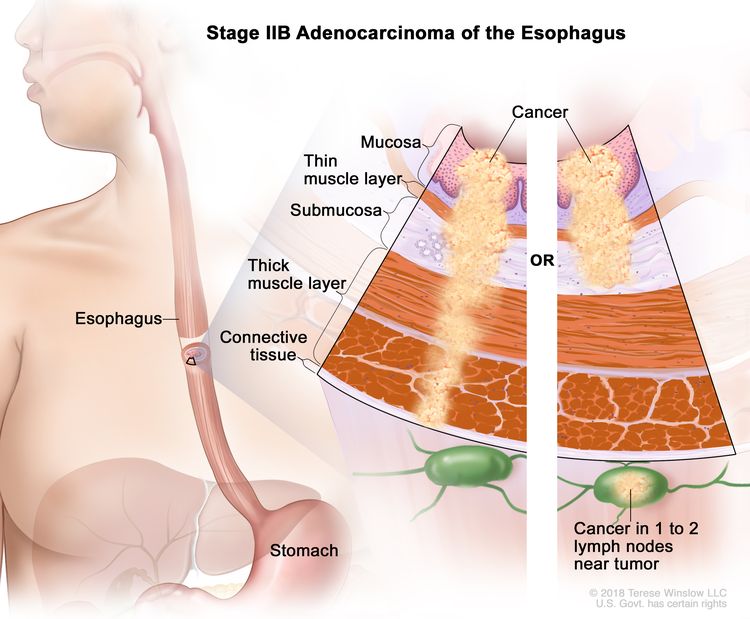

| Stage | TNM | Grade | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph nodes; M = distant metastasis; G = grade; p = pathological. | ||||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Esophageal and esophagogastric junction. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 185–202. | ||||

| IIA | T2, N0, M0 | G3 | T2 = Tumor invades the muscularis propria. |

|

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| G3 = Poorly differentiated, undifferentiated. | ||||

| T2, N0, M0 | GX | T2 = Tumor invades the muscularis propria. | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| GX = Grade cannot be assessed. | ||||

| IIB | T1, N1, M0 | Any | T1 = Tumor invades the lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, or submucosa. |

|

| –T1a = Tumor invades the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae. | ||||

| –T1b = Tumor invades the submucosa. | ||||

| N1 = Metastasis in one or two regional lymph nodes. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | ||||

| T3, N0, M0 | Any | T3 = Tumor invades adventitia. | ||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | ||||

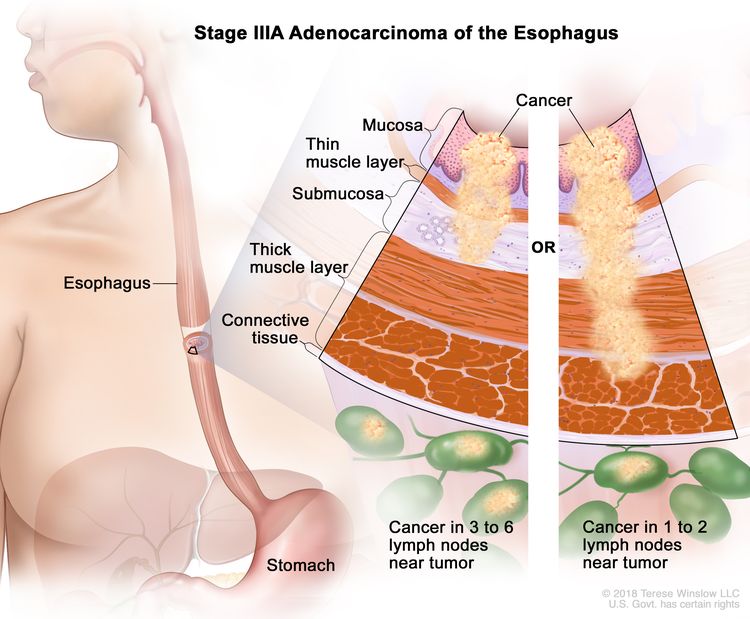

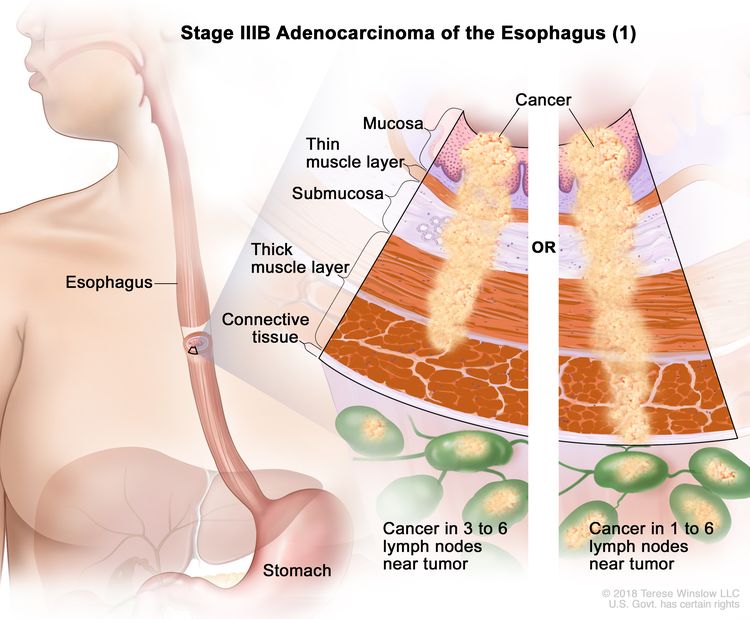

| Stage | TNM | Grade | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph nodes; M = distant metastasis; G = grade; p = pathological. | ||||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Esophageal and esophagogastric junction. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 185–202. | ||||

| IIIA | T1, N2, M0 | Any | T1 = Tumor invades the lamina propria, muscularis mucosae, or submucosa. |

|

| –T1a = Tumor invades the lamina propria or muscularis mucosae. | ||||

| –T1b = Tumor invades the submucosa. | ||||

| N2 = Metastasis in three to six regional lymph nodes. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | ||||

| T2, N1, M0 | Any | T2 = Tumor invades the muscularis propria. | ||

| N1 = Metastasis in one or two regional lymph nodes. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | ||||

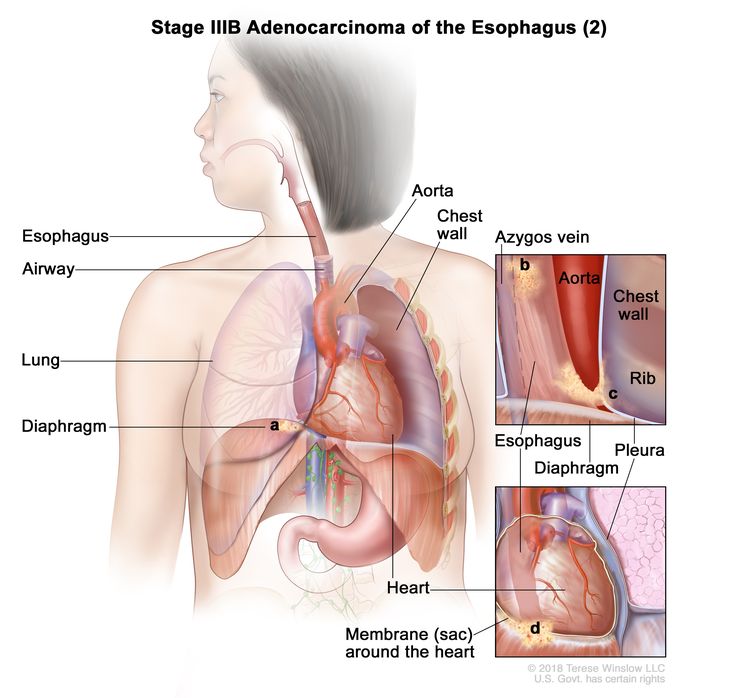

| IIIB | T2, N2, M0 | Any | T2 = Tumor invades the muscularis propria. |

|

| N2 = Metastasis in three to six regional lymph nodes. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | ||||

| T3, N1–2, M0 | Any | T3 = Tumor invades adventitia. | ||

| N1 = Metastasis in one or two regional lymph nodes. | ||||

| N2 = Metastasis in three to six regional lymph nodes. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | ||||

| T4a, N0–1, M0 | Any | –T4a = Tumor invades the pleura, pericardium, azygos vein, diaphragm, or peritoneum. |

|

|

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||||

| N1 = Metastasis in one or two regional lymph nodes. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | ||||

| Stage | TNM | Grade | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph nodes; M = distant metastasis; G = grade; p = pathological. | ||||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Esophageal and esophagogastric junction. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp. 185–202. | ||||

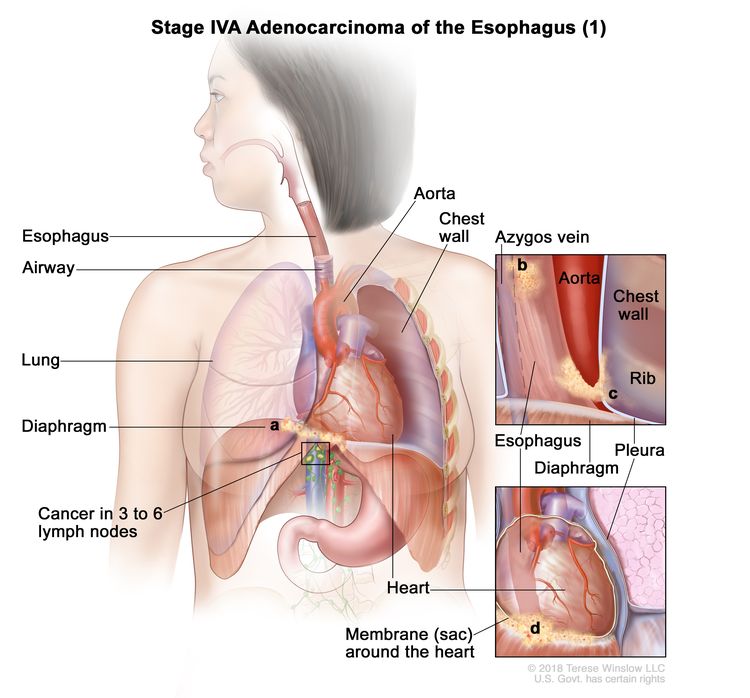

| IVA | T4a, N2, M0 | Any | –T4a = Tumor invades the pleura, pericardium, azygos vein, diaphragm, or peritoneum. |

|

| N2 = Metastasis in three to six regional lymph nodes. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | ||||

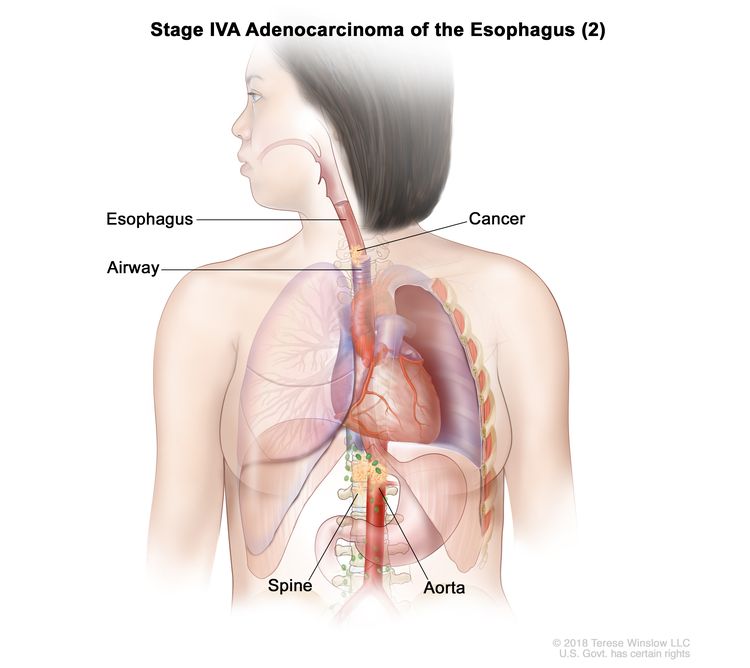

| T4b, N0–2, M0 | Any | –T4b = Tumor invades other adjacent structures, such as the aorta, vertebral body, or airway. |

|

|

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | ||||

| N1 = Metastasis in one or two regional lymph nodes. | ||||

| N2 = Metastasis in three to six regional lymph nodes. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | ||||

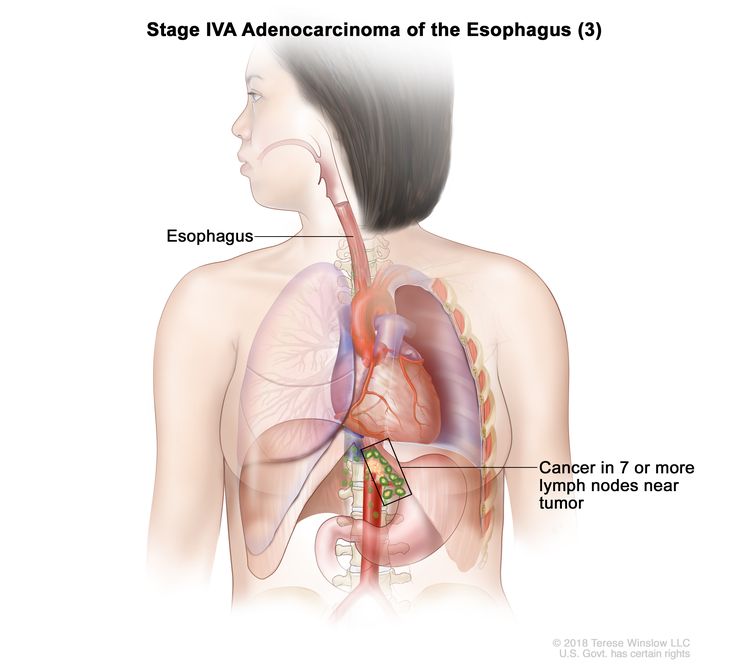

| Any T, N3, M0 | Any | Any T = See Table 1. |

|

|

| N3 = Metastasis in seven or more regional lymph nodes. | ||||

| M0 = No distant metastasis. | ||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | ||||

| IVB | Any T, Any N, M1 | Any | Any T = See Table 1. |

|

| Any N = See Table 1. | ||||

| M1 = Distant metastasis. | ||||

| Any G = See Table 1. | ||||

References

- Ziegler K, Sanft C, Zeitz M, et al.: Evaluation of endosonography in TN staging of oesophageal cancer. Gut 32 (1): 16-20, 1991. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tio TL, Coene PP, den Hartog Jager FC, et al.: Preoperative TNM classification of esophageal carcinoma by endosonography. Hepatogastroenterology 37 (4): 376-81, 1990. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Vazquez-Sequeiros E, Norton ID, Clain JE, et al.: Impact of EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration on lymph node staging in patients with esophageal carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc 53 (7): 751-7, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bonavina L, Incarbone R, Lattuada E, et al.: Preoperative laparoscopy in management of patients with carcinoma of the esophagus and of the esophagogastric junction. J Surg Oncol 65 (3): 171-4, 1997. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sugarbaker DJ, Jaklitsch MT, Liptay MJ: Thoracoscopic staging and surgical therapy for esophageal cancer. Chest 107 (6 Suppl): 218S-223S, 1995. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Luketich JD, Schauer P, Landreneau R, et al.: Minimally invasive surgical staging is superior to endoscopic ultrasound in detecting lymph node metastases in esophageal cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 114 (5): 817-21; discussion 821-3, 1997. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Krasna MJ, Reed CE, Nedzwiecki D, et al.: CALGB 9380: a prospective trial of the feasibility of thoracoscopy/laparoscopy in staging esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 71 (4): 1073-9, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Flamen P, Lerut A, Van Cutsem E, et al.: Utility of positron emission tomography for the staging of patients with potentially operable esophageal carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 18 (18): 3202-10, 2000. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Flamen P, Van Cutsem E, Lerut A, et al.: Positron emission tomography for assessment of the response to induction radiochemotherapy in locally advanced oesophageal cancer. Ann Oncol 13 (3): 361-8, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Weber WA, Ott K, Becker K, et al.: Prediction of response to preoperative chemotherapy in adenocarcinomas of the esophagogastric junction by metabolic imaging. J Clin Oncol 19 (12): 3058-65, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- van Westreenen HL, Westerterp M, Bossuyt PM, et al.: Systematic review of the staging performance of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol 22 (18): 3805-12, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Meyers BF, Downey RJ, Decker PA, et al.: The utility of positron emission tomography in staging of potentially operable carcinoma of the thoracic esophagus: results of the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z0060 trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 133 (3): 738-45, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rice TW, Kelsen D, Blackstone EH, et al.: Esophagus and Esophagogastric Junction. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp 185-202.

- Korst RJ, Rusch VW, Venkatraman E, et al.: Proposed revision of the staging classification for esophageal cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 115 (3): 660-69; discussion 669-70, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment Option Overview for Esophageal Cancer

For patients with minimally invasive resectable esophageal cancer, surgical resection alone offers the potential for cure. In contrast, therapeutic management for patients with locally advanced resectable esophageal cancer has evolved significantly over the last few decades. Because of the risk of distant metastases and local relapse, multimodality therapy with chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and surgical resection has become the standard of care.

The following combinations may provide effective palliation in individual cases:

| Stage (TNM Staging Criteria) | Treatment Options |

|---|---|

| Stage 0 Esophageal Cancer | Surgery |

| Endoscopic resection | |

| Stage I Esophageal Cancer | Chemoradiation therapy followed by surgery |

| Surgery alone | |

| Stage II Esophageal Cancer | Chemoradiation therapy followed by surgery |

| Surgery alone | |

| Chemotherapy followed by surgery | |

| Definitive chemoradiation therapy | |

| Stage III Esophageal Cancer | Chemoradiation therapy followed by surgery |

| Preoperative chemotherapy followed by surgery | |

| Definitive chemoradiation therapy | |

| Stage IV Esophageal Cancer | Chemoradiation therapy followed by surgery (for patients with stage IVA disease) |

| Chemotherapy, which has provided partial responses for patients with metastatic distal esophageal adenocarcinomas | |

| Adjuvant therapy for patients with completely resected (negative margins) esophageal adenocarcinoma, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, or gastroesophageal junction cancer who had residual pathological disease after concurrent chemoradiation therapy | |

| Immunotherapy and chemoimmunotherapy for patients with previously untreated, unresectable, advanced or metastatic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma | |

| Immunotherapy and chemoimmunotherapy for patients with previously untreated advanced or metastatic esophageal adenocarcinoma or gastroesophageal junction cancer | |

| Immunotherapy for patients who relapse after one prior line of standard therapy | |

| Nivolumab and chemotherapy for patients with adenocarcinoma | |

| Nd:YAG endoluminal tumor destruction or electrocoagulation | |

| Endoscopic-placed stents to provide palliation of dysphagia | |

| Radiation therapy with or without intraluminal intubation and dilation | |

| Intraluminal brachytherapy to provide palliation of dysphagia | |

| Clinical trials evaluating single-agent or combination chemotherapy | |

| Recurrent Esophageal Cancer | Palliative use of any of the other therapies, including supportive care |

| Immunotherapy and chemoimmunotherapy for patients with recurrent esophageal squamous cell carcinoma |

Surgery

Surgery (Barrett esophagus)

The prevalence of Barrett metaplasia in adenocarcinoma of the esophagus suggests that Barrett esophagus is a premalignant condition. Endoscopic surveillance of patients with Barrett metaplasia may detect adenocarcinoma at an earlier stage that is more amenable to curative resection. Strong consideration should be given to resection in patients with high-grade dysplasia in the setting of Barrett metaplasia.[7]

Surgery (esophageal cancer)

The survival rate of patients with esophageal cancer is poor. Surgical treatment of resectable esophageal cancers results in 5-year survival rates of 5% to 30%, with higher survival rates in patients with early-stage cancers.[8] Asymptomatic small tumors confined to the esophageal mucosa or submucosa are detected only by chance. Surgery is the treatment of choice for these small tumors. Once symptoms are present (e.g., dysphagia, in most cases), esophageal cancers have usually invaded the muscularis propria or beyond and may have metastasized to lymph nodes or other organs.

In some patients with partial esophageal obstruction, dysphagia may be relieved by placement of an expandable metallic stent [9] or by radiation therapy if the patient has disseminated disease or is not a candidate for surgery. Alternative methods of relieving dysphagia have been reported, including laser therapy and electrocoagulation to destroy intraluminal tumor.[10-12]

In the presence of complete esophageal obstruction without clinical evidence of systemic metastasis, surgical excision of the tumor with mobilization of the stomach to replace the esophagus has been the traditional means of relieving the dysphagia.

The optimal surgical approach for radical resection of esophageal cancer is not known. One approach advocates transhiatal esophagectomy with anastomosis of the stomach to the cervical esophagus. A second approach advocates abdominal mobilization of the stomach and transthoracic excision of the esophagus with anastomosis of the stomach to the upper thoracic esophagus or the cervical esophagus. One study concluded that transhiatal esophagectomy was associated with lower morbidity than was transthoracic esophagectomy with extended en bloc lymphadenectomy; however, median overall disease-free and quality-adjusted survival did not differ significantly.[13] Similarly, no differences in long-term quality of life (QOL) using validated QOL instruments have been reported.[14] More recently, minimally invasive approaches that offer potential advantages of smaller incisions, decreased intraoperative blood loss, fewer postoperative complications, and shorter hospital stays have emerged. However, the ability to obtain negative surgical margins, the adequacy of lymph node dissection, and long-term outcomes have not been fully established with this approach.[15]

In the United States, the median age of patients who present with esophageal cancer is 68 years.[16] The results of a retrospective review of 505 consecutive patients who were operated on by a single surgical team over 17 years found no difference in the perioperative mortality, median survival, or palliative benefit of esophagectomy on dysphagia when the patients older than 70 years were compared with their younger peers.[17][Level of evidence C1] All of the patients in this series were selected for surgery on the basis of potential operative risk. Age alone does not determine therapy for patients with potentially resectable disease.

Preoperative Chemotherapy Plus Anti-Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 Therapy and/or Immunotherapy

Fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel chemotherapy plus trastuzumab and pertuzumab

Evidence (fluorouracil [5-FU], leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel [FLOT] chemotherapy plus trastuzumab and pertuzumab):

- A multicenter phase II/III trial (NCT02581462) included patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive resectable gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (clinical T2 or larger or clinically node-positive). A total of 81 patients (61 with gastroesophageal cancer, 20 with gastric cancer) were enrolled during the phase II part of the study. Patients were randomly assigned to receive four preoperative and postoperative cycles of either FLOT alone (arm A, n = 41) or FLOT combined with trastuzumab and pertuzumab followed by nine cycles of trastuzumab and pertuzumab (arm B, n = 40). In the phase II part of the study, the primary end point was the rate of pathological complete response. The trial did not transition to phase III. It closed prematurely, after results of the JACOB trial were reported, which demonstrated that adding pertuzumab to trastuzumab and chemotherapy did not significantly improve overall survival (OS) in patients with HER2-positive metastatic gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer compared with placebo.[18]

- The pathological complete response rate was significantly improved for patients in arm B at 35%, compared with 12% for patients in arm A (P = .02).[18][Level of evidence B3]

- The rate of pathological lymph node negativity was higher for patients who received trastuzumab and pertuzumab (39% for arm A vs. 68% for arm B).

- The R0 resection rate was 90% for patients in arm A and 93% for patients in arm B. Surgical morbidity was also comparable, at 43% for patients in arm A and 44% for patients in arm B.

- The median disease-free survival (DFS) was 26 months for patients in arm A and not yet reached for patients in arm B (hazard ratio [HR], 0.58; P =.14).

- The 24-month DFS rates were 54% (95% confidence interval [CI], 38%–71%) in arm A and 70% (95% CI, 55%–85%) in arm B. The 24-month OS rates were 77% (95% CI, 63%–90%) in arm A and 84% (95% CI, 72%–96%) in arm B.

- More grade 3 or greater adverse events were reported among patients who received trastuzumab and pertuzumab, especially diarrhea (5% of patients in arm A and 41% of patients in arm B) and leukopenia (13% of patients in arm A and 23% of patients in arm B).

Preoperative Chemoradiation Therapy

On the basis of several randomized trial results, chemoradiation followed by surgery is a treatment option for patients with stages IB, II, III, and IVA esophageal cancer.

Phase III trials have compared preoperative concurrent chemoradiation therapy with surgery alone for patients with esophageal cancer.[19-25][Level of evidence A1] The benefit of neoadjuvant chemoradiation has been controversial because of contradictory results of early randomized studies.[19-22] However, the Chemoradiotherapy for Oesophageal Cancer Followed by Surgery Study (CROSS) has definitively demonstrated a survival benefit for preoperative chemoradiation compared with surgery alone in locally advanced esophageal cancer.[23]

For early-stage tumors, the role of preoperative chemoradiation remains controversial. Although the CROSS study included early-stage patients, the Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive (FFCD) 9901 study (NCT00047112),[25] which included only early-stage (stage I or II) patients, failed to demonstrate a survival advantage in this group of patients.

Evidence (preoperative chemoradiation therapy):

- The CROSS study randomly assigned 366 patients with resectable esophageal or junctional cancers to receive either surgery alone or weekly administration of carboplatin (dose titrated to achieve an AUC [area under the curve] of 2 mg/mL/minute) and paclitaxel (50 mg/m2 of BSA [body surface area]) and concurrent radiation therapy (41.4 Gy in 23 fractions) administered over 5 weeks. Most patients enrolled in the CROSS trial (75%) had adenocarcinoma.[23,26][Level of evidence A1]

- With a median follow-up of 84 months, preoperative chemoradiation was found to improve median OS from 24 months in the surgery-alone group to 48.6 months (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.53–0.88; P = .003). Median OS for patients with squamous cell carcinomas was 81.6 months in the preoperative chemoradiation group, compared with 21.1 months in the surgery-alone group (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.28–0.83; log-rank P = .008); for patients with adenocarcinomas, median OS was 43.2 months in the preoperative chemoradiation group, compared with 27.1 months in the surgery-alone group (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.55–0.98; log-rank P = .038).[26]

- Additionally, preoperative chemoradiation improved the rate of R0 resections (92% vs. 69%; P < .001). R0 is defined as complete resection with no tumor within 1 mm of resection margins.

- A complete pathological response was achieved in 29% of patients who underwent resection after chemoradiation therapy. A pathological complete response was observed in 23% of patients with adenocarcinoma, compared with 49% of patients with squamous cell carcinoma (P = .008).

- Postoperative complications and in-hospital mortality were equivalent in both groups. The most common hematologic side effects in the chemoradiation group were leukopenia (6%) and neutropenia (2%). The most common nonhematologic side effects were anorexia (5%) and fatigue (3%).

- With a median follow-up of 84 months, the 5-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate was 44% in the preoperative chemoradiation group, compared with 27% in the surgery-alone group (HR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.47–0.78). Preoperative chemoradiation therapy reduced locoregional recurrence from 34% to 14% (P < .001) and peritoneal carcinomatosis from 14% to 4% (P < .001). There was a small but significant effect on hematogenous dissemination in favor of the chemoradiation therapy group (35% vs. 29%; P = .025).[24,26][Level of evidence B1]

- A multicenter,

prospective, randomized trial compared preoperative combined chemotherapy

(i.e., cisplatin) and radiation therapy (37 Gy in 3.7-Gy fractions) versus surgery alone in patients with squamous cell carcinoma.[19][Level of evidence A1]

- The study showed no improvement in OS and a significantly higher postoperative mortality rate (12% vs. 4%) in the combined-modality arm.

- In

patients with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, a single-institution phase III

trial was conducted in patients treated with induction chemoradiation therapy consisting of 5-FU,

cisplatin, and 40 Gy (in 2.67-Gy fractions) plus surgery compared with resection

alone.[20][Level of evidence A1]

- The results demonstrated a modest survival benefit of 16 months for combined modality therapy versus 11 months for surgery alone.

- A subsequent single-institution trial randomly assigned patients (75% with

adenocarcinoma) to 5-FU, cisplatin, vinblastine, and radiation

therapy (1.5 Gy twice daily to a total of 45 Gy) plus resection versus

esophagectomy alone.[21][Level of evidence A1]

- At a median follow-up of more than 8 years, there was no significant difference between the surgery alone and combined modality therapy with respect to median survival (17.6 months vs. 16.9 months), OS rate (16% vs. 30% at 3 years), or DFS rate (16% vs. 28% at 3 years).

- An intergroup trial (CALGB-9781 [NCT00003118]) planned to randomly assign 475 patients with resectable squamous cell or adenocarcinoma of the thoracic esophagus to treatment with preoperative chemoradiation therapy (5-FU, cisplatin, and 50.4 Gy) followed by esophagectomy and nodal dissection or surgery alone. The trial was closed as a result of poor patient accrual; however, results from the 56 enrolled patients, with a median follow-up of 6 years, were reported.[22][Level of evidence A1]

- The median survival was 4.48 years (95% CI; range, 2.4–not estimable) for trimodality therapy versus 1.79 years (95% CI, 1.41–2.59) for surgery alone (P = .002), with a 5-year OS rate of 39% for trimodality therapy (95% CI, 21%–57%) versus 16% for surgery alone (95% CI, 5%–33%).

- To further evaluate the impact of neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy for early-stage disease, the FFCD 9901 study randomly assigned 195 patients with stage I or stage II esophageal cancer to receive surgery alone or neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy (45 Gy in 25 fractions administered with two courses of 5-FU [800 mg/m2] and cisplatin [75 mg/m2]) followed by surgery.[25][Level of evidence A1]

- At interim analysis, accrual to the study was stopped early because of futility.

- With a median follow-up of 94 months, there was no significant improvement in 3-year OS rates with chemoradiation (48% vs. 53%; P = .94); there was a significantly higher postoperative mortality rate of 11.1% versus 3.4% (P = .049).

- The NRG Oncology/RTOG-1010 trial (NCT01196390) evaluated the addition of trastuzumab to trimodality treatment (paclitaxel plus carboplatin and radiotherapy, followed by surgery) in patients with untreated HER2-overexpressing esophageal adenocarcinoma. This phase III trial entered 606 patients for HER2 assessment. A total of 203 patients with HER2-positive disease were randomly assigned to receive chemoradiation therapy plus trastuzumab (n = 102) or chemoradiation therapy alone (n = 101). The primary end point was DFS. The median duration of follow-up was 2.8 years.[27]

- The median DFS was 19.6 months (95% CI, 13.5–26.2) for patients who received chemoradiation therapy plus trastuzumab and 14.2 months (10.5–23.0) for patients who received chemoradiation therapy alone (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.71–1.39; log-rank P = .97).[27][Level of evidence B1]

- Grade 3 treatment-related adverse events occurred in 41 of 95 patients (43%) who received trastuzumab and 52 of 96 patients (54%) of patients who received chemoradiation therapy alone. Grade 4 treatment-related adverse events occurred in 20 patients (21%) who received trastuzumab and 21 patients (22%) who received chemoradiation therapy alone.

- There were five treatment-related deaths in the trastuzumab group (bronchopleural fistula, esophageal anastomotic leak, lung infection, sudden death, and death not otherwise specified), and three deaths in the chemoradiation therapy group (two multiorgan failure and one sepsis).

In conclusion, this trial confirmed that trastuzumab does not have a role in the preoperative treatment of HER2-positive esophageal or gastroesophageal cancer, either with chemotherapy alone or with chemoradiation therapy.

Preoperative Chemotherapy

The effects of preoperative chemotherapy are being evaluated in randomized trials. Several studies have demonstrated a survival benefit with preoperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone.[28-30] However, one large randomized study failed to confirm a survival benefit with preoperative chemotherapy.[31] Compared with preoperative chemotherapy alone, preoperative chemoradiation therapy improves pathological response and may improve outcomes.[32]

Evidence (preoperative chemotherapy):

- An intergroup trial (NCT00525785) randomly assigned 440 patients with local and operable esophageal cancer of any cell type to three cycles of preoperative 5-FU and cisplatin followed by surgery and two additional cycles of chemotherapy versus surgery alone.[31][Level of evidence A1]

- After a median follow-up of 55 months, there were no significant differences in median survival between the chemotherapy-plus-surgery group (14.9 months) and the surgery-alone group (16.1 months). The median 2-year survival rate was 35% in the chemotherapy-plus-surgery group and 37% in the surgery-alone group.

- The addition of chemotherapy did not increase the morbidity associated with surgery.

- The Medical Research Council Oesophageal Cancer Working Party randomly assigned 802 patients with resectable esophageal cancer, also of any cell type, to two cycles of preoperative 5-FU and cisplatin followed by surgery versus surgery alone.[28][Level of evidence A1]

- At a median follow-up of 37 months, median survival was significantly improved in the preoperative chemotherapy arm (16.8 months vs. 13.3 months with surgery alone; 95% CI), as was the 2-year OS rate (43% in the preoperative chemotherapy arm and 34% in the surgery-alone arm; 95% CI).

The interpretation of the results from the intergroup and preoperative chemotherapy trials is challenging because T or N staging was not reported, and prerandomization and radiation could be offered at the discretion of the treating oncologist.

- The Japanese Clinical Oncology Group randomly assigned 330 patients with clinical stage II or III, excluding T4, squamous cell carcinomas to receive either two cycles of preoperative cisplatin and 5-FU followed by surgery or surgery followed by postoperative chemotherapy of the same regimen. A planned interim analysis was conducted after patient accrual. Although the primary end point of PFS was not met, there was a significant benefit in OS among patients treated with preoperative chemotherapy (P = .01). As a result of these findings, the Data and Safety Monitoring Committee recommended early closure of the study.[29][Level of evidence A3]

- With a median follow-up of 61 months, the 5-year OS rate was 55% among patients treated with preoperative chemotherapy, compared with 43% among patients treated with postoperative chemotherapy (P = .04). However, there was no significant difference between groups with respect to PFS (5-year PFS rate, 39% vs. 44%; P = .22).

- Additionally, there were no significant differences between the two groups with respect to postoperative complications or treatment-related toxicities.

- The Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte contre le Cancer and the FFCD randomly assigned 224 patients with resectable adenocarcinoma of the lower esophagus, gastroesophageal junction, or stomach to receive either perioperative chemotherapy and surgery (n = 113) or surgery alone (n = 111). Chemotherapy consisted of two or three preoperative cycles of intravenous (IV) cisplatin (100 mg/m2) on day 1 and continuous IV infusion of 5-FU (800 mg/m2) for 5 consecutive days (day 1–5) every 28 days, and three or four postoperative cycles of the same regimen.[30][Level of evidence A1]

- Perioperative chemotherapy was associated with an improved 5-year OS rate (38% vs. 24%; HR, 0.69; P = .02).

- Grade 3 and 4 toxicity occurred in 38% of patients treated with perioperative chemotherapy, but there was no increase in postoperative morbidity.

- The Preoperative Chemotherapy or Radiochemotherapy in Esophago-gastric Adenocarcinoma Trial (POET) sought to evaluate the additional benefit of radiation therapy to preoperative chemotherapy. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either induction chemotherapy (15 weeks) followed by surgery or chemotherapy (12 weeks) followed by chemoradiation therapy (3 weeks) and surgery.[32][Level of evidence A1]

- The study was closed early because of poor accrual. In total, 126 patients were randomly assigned.

- Preoperative radiation therapy yielded 3-year survival rates of 27% to 47% (log-rank P = .07). The postoperative mortality rate was nonsignificantly increased in the chemoradiation therapy group (10.2% vs. 3.8%; P = .26).

Perioperative Chemotherapy

- A trial that included patients with resectable adenocarcinoma of the stomach, esophagogastric junction, or lower esophagus randomly assigned 250 patients to receive perioperative chemotherapy and surgery and 253 patients to receive surgery alone. Chemotherapy consisted of three preoperative and three postoperative cycles of IV epirubicin (50 mg/m2) and cisplatin (60 mg/m2) on day 1, and a continuous IV infusion of 5-FU (200 mg/m2 per day) for 21 days. The primary end point was OS.[33]

- After a median follow-up of 4 years, 149 patients in the perioperative chemotherapy group and 170 patients in the surgery-alone group had died.

- Compared with the surgery-alone group, the perioperative chemotherapy group had a higher likelihood of OS (HRdeath, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.60–0.93; P = .009). The 5-year survival rate was 36.3% in the perioperative chemotherapy group (95% CI, 29.5%–43.0%) and 23% (95% CI, 16.6%–29.4%) in the surgery-alone group.[33][Level of evidence A1]

- The PFS rate was also improved in the perioperative chemotherapy group (HRprogression, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.53–0.81; P < .001) compared with the surgery-alone group.

- The rate of postoperative complications was similar in the two groups; 46% in the perioperative chemotherapy group and 45% in the surgery-alone group. The number of deaths within 30 days after surgery was also similar between the two groups.

- An open-label, randomized, phase II/III trial compared the efficacy and safety of the docetaxel-based triplet FLOT regimen with the combination of epirubicin and cisplatin plus either 5-FU given as a continuous infusion or capecitabine given orally. The trial included 716 patients with adenocarcinoma in clinical stage cT2 or higher, node-positive stage (cN+), or both, or resectable tumors with no evidence of distant metastases. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either: (1) ECF/ECX (three preoperative and three postoperative 3-week cycles of epirubicin [50 mg/m2] and cisplatin [60 mg/m2] on day 1 plus either 5-FU [200 mg/m2] given as a continuous infusion or capecitabine [1,250 mg/m2] orally on days 1 to 21), or (2) FLOT (four preoperative and four postoperative 2-week cycles of docetaxel [50 mg/m2], oxaliplatin [85 mg/m2], leucovorin [200 mg/m2], and 5-FU [2,600 mg/m2] as a 24-hour infusion on day 1). The primary end point of the trial was OS (superiority) in the intention-to-treat population.[34]

- OS was longer in the FLOT group than the ECF/ECX group (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.63–0.94). The median OS was 50 months in the FLOT group (38.33–not reached) and 35 months in the ECF/ECX group (27.35–46.26).[34][Level of evidence A1]

- The number of patients with related serious adverse events (including those occurring during a hospital stay for surgery) was similar between the two groups: 96 patients (27%) in the ECF/ECX group and 97 patients (27%) in the FLOT group.

- The number of deaths due to toxicity (two [<1%]) was similar in both groups. Hospitalization for toxicity occurred in 94 patients (26%) in the ECF/ECX group and 89 patients (25%) in the FLOT group.

- The ESOPEC trial (NCT02509286) compared (1) perioperative FLOT (four 2-week cycles of chemotherapy before surgery and four 2-week cycles of chemotherapy after surgery) and surgery with (2) neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy with the CROSS regimen (41.4 Gy of radiation therapy plus carboplatin and docetaxel) followed by surgery. The trial enrolled 438 patients with clinical (c)T1, cN+, cM0 or cT2–4a, any cN, cM0 resectable esophageal adenocarcinoma. Patients were assigned to the FLOT group (n = 221) or the CROSS group (n = 217). The primary end point was OS.[35]

- With a median follow-up of 55 months, the 3-year OS rate was 57.4% (95% CI, 50.1%–64.0%) in the FLOT group and 50.7% (95% CI, 43.5%–57.5%) in the CROSS group (HRdeath, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.53–0.92; P = .01). The median OS was 66 months (95% CI, 36–not estimable) in the FLOT group and 37 months (95% CI, 28–43) in the CROSS group.[35][Level of evidence A1]

- The 3-year PFS rate was 51.6% (95% CI, 44.3%–58.4%) in the FLOT group and 35.0% (95% CI, 28.4%–41.7%) in the CROSS group (HRdisease progression or death, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.51–0.85).

- Neoadjuvant treatment was given to 403 patients: 207 patients in the FLOT group and 196 patients in the CROSS group. In the FLOT group 193 patients (89%) received four full cycles of chemotherapy before surgery, and 118 patients (53%) received four full cycles of chemotherapy after surgery. In the CROSS group, 147 patients (68%) received five full cycles of chemotherapy.

- Surgery was performed in 374 patients: 192 patients in the FLOT group and 179 patients in the CROSS group. R0 resection occurred in 182 of 193 patients (94.3%) in the FLOT group and in 172 of 181 patients (95.0%) in the CROSS group.

- Pathological complete response after surgery, defined as a pathological stage of ypT0 ypN0 (no residual invasive cancer in the resected primary tumor and lymph nodes), was seen in 32 of 192 patients (16.7%) in the FLOT group and 18 of 179 patients (10.1%) in the CROSS group.

- At 90 days after surgery, 3.1% of patients in the FLOT group and 5.6% of patients in the CROSS group had died.

- The study noted grade 3 or higher adverse events that occurred in 5% or more of patients. In the FLOT group, those adverse effects included neutropenia (19.8%), diarrhea (6.8%), leukopenia (6.3%), and pneumonia (5.8%). In the CROSS group, those adverse effects included leukopenia (9.7%) and pneumonia (9.2%).

In the ESOPEC trial, patients randomly assigned to the CROSS arm did not receive 1 year of adjuvant nivolumab. In the CheckMate 577 trial, 1 year of adjuvant nivolumab improved DFS when compared with placebo in patients who had resected specimens that did not show pathological complete responses. However, OS data from CheckMate 577 have not been published.

Definitive Chemoradiation Therapy

For patients who are deemed either medically inoperable or have tumors that are unresectable, the efficacy of definitive chemoradiation has been established in numerous randomized controlled trials.[36,37] For patients with squamous cell carcinomas of the esophagus, definitive chemoradiation may offer equivalent outcomes, compared with preoperative chemoradiation followed by surgical resection.[38,39]

Evidence (definitive chemoradiation):

- A Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trial (RTOG-8501) randomly assigned patients to receive radiation therapy alone (64 Gy in 32 fractions) or chemoradiation (50 Gy in 25 fractions) with concurrent cisplatin (75 mg/m2) and continuous-infusion 5-FU (1,000 mg/m2 on days 1 to 4 in weeks 1 and 5 followed by two additional cycles of chemotherapy administered 3 weeks apart).[36][Level of evidence A1]

- There was an improvement in the 5-year survival rate for the combined modality group (27% vs. 0%).

- An 8-year follow-up of this trial demonstrated an OS rate of 22% for patients who received chemoradiation therapy.

- Intergroup-0123 (RTOG-9405 [NCT00002631]) was conducted in an attempt to improve upon the results

of RTOG-8501. Intergroup-0123 randomly assigned 236 patients with

localized esophageal tumors to undergo chemoradiation with high-dose radiation therapy

(64.8 Gy) and four monthly cycles of 5-FU and cisplatin versus conventional-dose radiation therapy (50.4 Gy) and the same chemotherapy schedule.[37][Level of evidence A1]

- Although originally designed to accrue 298 patients, this trial was closed in 1999 after a planned interim analysis showed that it was statistically unlikely that there would be any advantage to using high-dose radiation.

- At a 2-year median follow-up, no statistically significant differences in median survival were observed between the high-dose and conventional-dose radiation therapy arms (13 months vs. 18 months), 2-year survival rates (31% vs. 40%), or local and regional failure rates (56% vs. 52%).

- There was a higher treatment mortality rate in the higher-dose arm (9% vs. 2%). However, 7 of 11 deaths in the high-dose arm occurred in patients who had received 50.4 Gy or less.

- An Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial (EST-1282) evaluated 135

patients.[40][Level of evidence A1]

- This trial showed that chemotherapy plus radiation therapy provided a better 2-year survival rate than did radiation therapy alone, similar to results from the intergroup trial.

- The PRODIGE5/ACCORD17 trial (NCTE) compared the efficacy and safety of oxaliplatin, 5-FU, and leucovorin calcium (FOLFOX) versus 5-FU and cisplatin as the chemotherapy backbone among patients treated with definitive chemoradiation for localized esophageal cancer. In this multicenter, randomized, phase II and III trial, 267 patients were randomly assigned to receive either six cycles of FOLFOX (three cycles concomitant with radiation therapy), oxaliplatin (85 mg/m2), leucovorin (200 mg/m2), bolus 5-FU (400 mg/m2), and infusion 5-FU (1,600 mg/m2 over 46 hours) or four cycles of 5-FU (1,000 mg/m2 for 4 days) and cisplatin (75 mg/m2 on day 1). All patients received radiation therapy (50 Gy in 25 fractions).[41][Level of evidence B1]

- With a median follow-up of 25.3 months, there was no significant difference in PFS (9.7 months with FOLFOX vs. 9.4 months with 5-FU and cisplatin; P = .64).

- There was one death caused by toxicity in the FOLFOX group versus six deaths in the 5-FU and cisplatin arm (P = .066).

- There were no significant differences in grade 3 or 4 adverse events between treatment groups. Among toxicities of all grades, paresthesia, sensory neuropathy, and increases in aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase were more common in the FOLFOX group; increases in serum creatinine, mucositis, and alopecia were more common in the 5-FU and cisplatin group.

- A phase III German trial also compared induction chemotherapy (three courses of bolus 5-FU, leucovorin, etoposide, and cisplatin) followed by chemoradiation therapy (cisplatin, etoposide, and 40 Gy) followed by surgery (arm A), or the same induction chemotherapy followed by chemoradiation therapy (at least 65 Gy) without surgery (arm B) for patients with T3 or T4 squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. OS was the primary outcome.[38][Level of evidence A1]

- The analysis of 172 eligible randomly assigned patients showed that OS rates at 2 years were not statistically significantly different between the two treatment groups (arm A, 39.9%; 95% CI, 29.4%–50.4%; arm B, 35.4%; 95% CI, 25.2%–45.6%; log-rank test for equivalence with 0.15, P < .007).

- The local 2-year PFS rate was higher in the surgery group (64.3%; 95% CI, 52.1%–76.5%) than in the chemoradiation therapy group (40.7%; 95% CI, 28.9%–52.5%; HR for arm B vs. arm A, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.3–3.5; P < .003).

- The treatment-related mortality rate was higher in the surgery group (12.8%) than in the chemoradiation therapy group (3.5%) (P < .03).

- FFCD 9102 (NCTE) randomly assigned 259 patients with T3N0–1M0 thoracic esophageal cancer to receive either two cycles of 5-FU and cisplatin (days 1–5 and 22–26) and either conventional radiation therapy (46 Gy in 4.5 weeks) or split course (15 Gy, days 1–5 and 22–26). Patients with response were then randomly assigned to receive either surgical resection (arm A) or continuation of chemoradiation (arm B: three cycles of 5-FU plus cisplatin and either conventional 20 Gy or split-course 15 Gy radiation therapy).[39][Level of evidence A1]

- Of the 259 randomly assigned patients, 230 (89%) had squamous cell carcinoma, and 29 patients (11%) had adenocarcinomas.

- The 2-year OS rate was 34% in patients randomly assigned to receive surgery versus 40% in patients randomly assigned to receive definitive chemoradiation (HR, 0.90; P = .44). Median survival was 17.7 months for surgery and 19.3 months for definitive chemoradiation.

- The 3-month mortality rate was 9.3% in the surgery arm, compared with 0.8% in the chemoradiation arm (P = .002).

Adjuvant Therapy

Evidence (adjuvant therapy):

- A global, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluated a checkpoint inhibitor as adjuvant therapy in 794 patients with esophageal or gastroesophageal junction cancer. Adults with a performance status of 0 or 1 and R0 stage II or III disease who had received neoadjuvant chemoradiation therapy and had residual pathological disease were included. Patients were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive either nivolumab (240 mg every 2 weeks for 16 weeks) followed by nivolumab (480 mg every 4 weeks) (532 patients) or matching placebo (262 patients). Patients were enrolled regardless of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression. The maximum duration of the trial intervention period was 1 year. The primary end point was DFS. The median follow-up was 24.4 months.[42][Level of evidence B1]

- The median DFS was 22.4 months (95% CI, 16.6–34.0) among patients who received nivolumab, compared with 11.0 months (95% CI, 8.3–14.3) among patients who received placebo. The HRdisease recurrence or death was 0.69 (96.4% CI, 0.56–0.86; P < .001).

- Median DFS was evaluated across a prespecified subgroup according to histological type. Among patients with adenocarcinoma, the median DFS was 19.4 months in the 376 patients who received nivolumab (95% CI, 15.9–29.4), compared with 11.1 months in the 187 patients who received the placebo (95% CI, 8.3–16.8); the HRdisease recurrence or death was 0.75 (95% CI, 0.59–0.96). Among patients with squamous cell carcinoma, the median DFS was 29.7 months (95% CI, 14.4 to not estimable) in the 155 patients who received nivolumab, compared with 11 months (95% CI, 7.6–17.8) in the 75 patients who received the placebo; the HRdisease recurrence or death was 0.61 (95% CI, 0.42–0.88).

- HRs for disease recurrence or death were remarkably close between the 570 patients whose tumors expressed less than 1% of PD-L1 (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.57–0.92) and the 129 patients whose tumors expressed 1% or more of PD-L1 (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.45–1.24).

- Grade 3 or 4 adverse events of any cause occurred in 183 of 532 patients (34%) in the nivolumab group and 84 of 260 patients (32%) in the placebo group, and serious adverse events of any grade occurred in 30% of the patients in each group (nivolumab: 158 of 532; placebo: 78 of 260). Adverse events that were considered by the investigators to be related to the trial regimen were more common with nivolumab than with placebo, including grade 3 or 4 events (nivolumab: 71 of 532 patients [13%]; placebo: 15 of 260 patients [6%]) and events leading to discontinuation of therapy (nivolumab: 48 of 532 patients [9%]; placebo: 8 of 260 patients [3%]).

- OS data have not been reported for this study.

Given the positive results for the use of nivolumab after chemoradiation therapy and surgery in patients with esophageal cancer, an ongoing study will determine whether the adjuvant use of checkpoint inhibitor therapy improves outcomes in patients undergoing definitive chemoradiation therapy without surgery (KEYNOTE-975 [NCT04210115]).

Immunotherapy and Chemoimmunotherapy

Immunotherapy and chemoimmunotherapy for patients with squamous cell carcinoma

Phase III randomized trials have compared chemotherapy with chemoimmunotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced squamous cell carcinoma.[43-45]

Evidence (immunotherapy and chemoimmunotherapy for patients with squamous cell carcinoma):

- In the CheckMate 648 trial (NCT03143153), 970 adults with previously untreated, unresectable advanced, recurrent, or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma were enrolled, regardless of tumor cell PD-L1 expression. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either nivolumab (240 mg every 2 weeks) plus chemotherapy with 5-FU and cisplatin (every 4 weeks), nivolumab (3 mg/kg every 2 weeks) plus ipilimumab (1 mg/kg every 6 weeks), or chemotherapy alone. Primary end points for all groups were OS and PFS per blinded independent central review in patients with tumor cell PD-L1 expression of 1% or more (observed in 49% of patients). Further analyses included all patients regardless of PD-L1 status.[43]

- In patients with PD-L1-positive disease, the median OS was 15.4 months for patients who received nivolumab plus chemotherapy (95% CI, 11.9–19.5; n = 158), 13.7 months for patients who received nivolumab plus ipilimumab (95% CI, 11.2–17.0; n = 158), and 9.1 months for patients who received chemotherapy alone (95% CI, 7.7–10.0; n = 157). The corresponding HR (vs. chemotherapy) was 0.54 (99.5% CI, 0.37–0.8; P < .0001) for patients who received nivolumab plus chemotherapy and 0.64 (98.6% CI, 0.46–0.9; P < .001) for patients who received nivolumab plus ipilimumab.[43][Level of evidence A1]

- A statistically significant improvement in median OS, compared with chemotherapy, was also observed in all randomized patients, irrespective of PD-L1 status. Median OS was 13.2 months for patients who received nivolumab plus chemotherapy (95% CI, 11.1–15.7; n = 321), 12.8 months for patients who received nivolumab plus ipilimumab (95% CI, 11.3–15.5; n = 325), and 10.7 months for patients who received chemotherapy alone (95% CI, 9.4–11.9; n = 324). The corresponding HR (vs. chemotherapy) was 0.74 (99.1% CI, 0.58–0.96; P = .0021) for patients who received nivolumab plus chemotherapy and 0.78 (98.2% CI, 0.62–0.98; P = .011) for patients who received nivolumab plus ipilimumab.[43][Level of evidence A1]

- However, among patients whose tumors expressed less than 1% of PD-L1, OS was not significantly changed by the addition of nivolumab to chemotherapy (n = 329; median OS, 12.2 months with chemotherapy and 12 months with nivolumab plus chemotherapy) or by the combination of nivolumab with ipilimumab (n = 330; median OS, 12.2 months with chemotherapy and 12 months with nivolumab plus ipilimumab).

- Grade 3 or higher adverse events occurred in 147 patients (47%) who received nivolumab plus chemotherapy, 102 patients (32%) who received nivolumab plus ipilimumab, and 108 patients (36%) who received chemotherapy alone. No new safety signals were observed.

- The results of ESCORT-1st (NCT03691090), a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial conducted in China, corroborated the positive impact of checkpoint inhibitors combined with first-line chemotherapy on patient survival. In this trial, 596 patients with previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic esophageal squamous cell cancer were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive either the humanized anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody camrelizumab (200 mg; n = 298) or placebo (n = 298). Patients in both groups also received up to 6 cycles of paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) and cisplatin (75 mg/m2). All drugs were given IV every 3 weeks. Co-primary end points were OS and independent review committee (IRC)-assessed PFS.[44]

- With a median follow-up of 10.8 months, patients who received camrelizumab plus chemotherapy had significantly improved OS compared with patients who received placebo plus chemotherapy (median OS, 15.3 months [95% CI, 12.8–17.3] vs. 12.0 months [11.0–13.3]; HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.56–0.88; one-sided P = .0010).

- Grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events occurred in 189 patients (63.4%) in the camrelizumab group and 201 patients (67.7%) in the placebo group. Treatment-related deaths occurred in 9 patients (3.0%) in the camrelizumab group and 11 patients (3.7%) in the placebo group.

Camrelizumab is only approved for use in China.

- In KEYNOTE-590 (NCT03189719), a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, phase III trial, 1,020 patients with previously untreated, locally advanced, unresectable, or metastatic esophageal cancer or Siewert type 1 gastroesophageal junction cancer (regardless of PD-L1 status) were screened.[45] A total of 749 patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive either pembrolizumab (200 mg) or placebo plus chemotherapy (5-FU at 800 mg/m2 on days 1–5 and cisplatin 80 mg/m2 on day 1 [for up to 6 cycles]). Treatment was repeated once every 3 weeks for up to 35 cycles. The primary end points were: (1) OS in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and a PD-L1 combined positive score (CPS) of 10 or more, and (2) OS and PFS in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, patients with a PD-L1 CPS of 10 or more irrespective of the histology, and all randomized patients. A total of 548 enrolled patients (73%) had squamous cell histology, 286 of whom (52%) had a CPS of 10 or more.

- At the first interim analysis (after a median follow-up of 22.6 months), patients who received pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy had superior OS compared with patients who received placebo plus chemotherapy for each of the following subgroups:[45][Level of evidence A1]

- Patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and a PD-L1 CPS of 10 or more (median OS, 13.9 months vs. 8.8 months; HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.43–0.75; P < .0001).

- Patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (OS, 12.6 months vs. 9.8 months; HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.60–0.88; P = .0006).

- Patients with a PD-L1 CPS of 10 or more (OS, 13.5 months vs. 9.4 months; HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.49–0.78; P < .0001).

- All randomized patients (OS, 12.4 months vs. 9.8 months; HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.62–0.86; P < .0001).

- The 24-month OS rate in each of the above subgroups was double in the pembrolizumab and chemotherapy group compared with the placebo and chemotherapy group (approximately 30% vs. 15%).

- Grade 3 or higher treatment-related adverse events occurred in 266 patients (72%) in the pembrolizumab group and 250 patients (68%) in the placebo group.

Notably, in an exploratory analysis in patients with a PD-L1 CPS of less than 10, median OS was 10.5 months in the pembrolizumab and chemotherapy group versus 10.6 months in the placebo and chemotherapy group (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.68–1.10).

- At the first interim analysis (after a median follow-up of 22.6 months), patients who received pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy had superior OS compared with patients who received placebo plus chemotherapy for each of the following subgroups:[45][Level of evidence A1]

Immunotherapy and chemoimmunotherapy for patients with adenocarcinoma

In 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved nivolumab in combination with fluoropyrimidine- and platinum-containing chemotherapy for patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer, gastroesophageal junction cancer, and esophageal adenocarcinoma after the publication of the results of the CheckMate-649 trial.[46]

Evidence (immunotherapy and chemoimmunotherapy for patients with adenocarcinoma):

- In a randomized, open-label, international, phase III study (CheckMate-649 [NCT02872116]), 1,581 patients (including 955 with a PD-L1 CPS ≥5) with HER2-negative gastric, gastroesophageal junction, or esophageal adenocarcinomas were randomly assigned (1:1:1) (1:1 after enrollment in the nivolumab-plus-ipilimumab group was closed). A total of 789 patients (473 with a PD-L1 CPS ≥5) were assigned to receive nivolumab and chemotherapy (nivolumab 360 mg with capecitabine and oxaliplatin every 3 weeks, or nivolumab 240 mg with FOLFOX every 2 weeks). A total of 792 patients (482 with a PD-L1 CPS ≥5) were assigned to receive chemotherapy alone (capecitabine and oxaliplatin every 3 weeks or FOLFOX every 2 weeks). Disease site of origin was as follows: 1,100 patients (70%) had gastric adenocarcinoma, 260 patients (17%) had gastroesophageal junction carcinoma, and 211 patients (13%) had esophageal adenocarcinoma.[46]