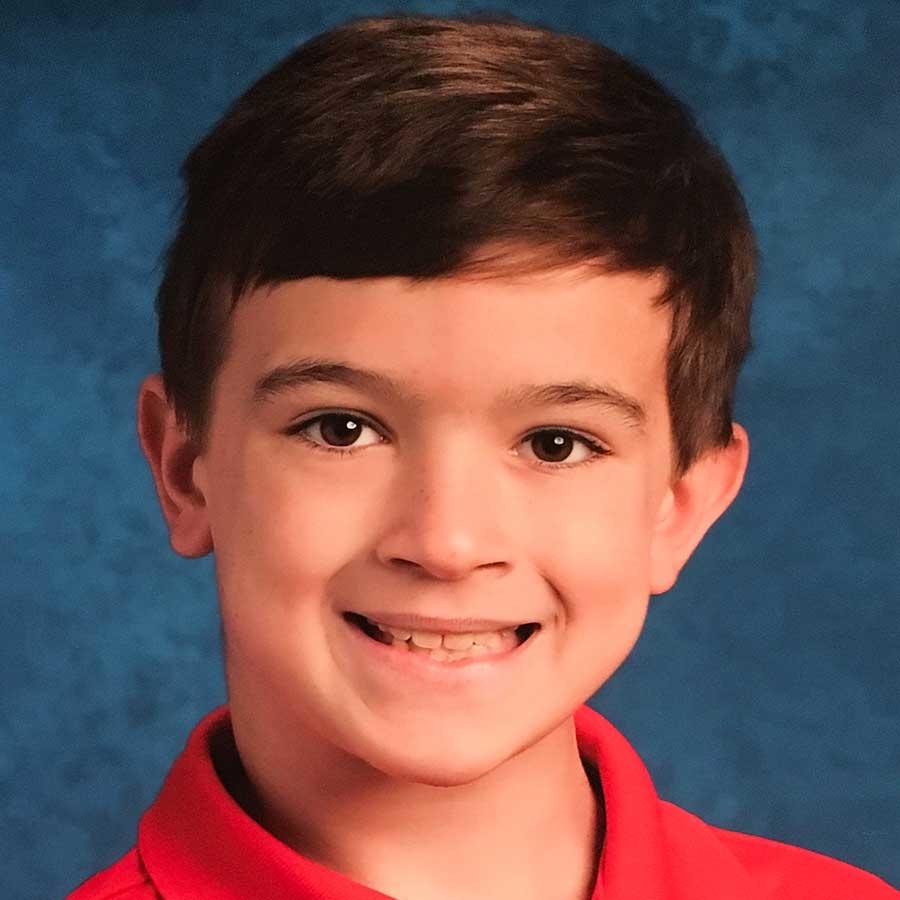

When 9-year-old Philip ran out of treatment options for his neurofibroma tumors in April 2015, his doctors directed his family to NCI. NCI was leading the only treatment trial in the nation for children with tumors caused by neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), a genetic disorder in which painful and often disfiguring tumors of the nerves can grow on or under the skin. These tumors are generally benign, but about 10% of people with NF1 will develop a cancerous neurofibroma. There are currently no Food and Drug Administration-approved therapies for NF1.

Philip’s experience with NF1 began when he was 6 years old, with the detection, diagnosis, and removal of a tumor on his neck. “We’d never heard of NF1 before; our world changed,” said Renie, Philip’s mother. Unfortunately, the tumor regrew over the next few years. After additional surgery, routine imaging scans revealed that the tumor was growing again, and, over a 6-month period, it grew from the size of a ping pong ball to the size of a tennis ball. In addition, other tumors had developed. The tumor on his neck was particularly concerning because it could obstruct his airway or cause other complications. “We felt like we were one step away from disaster,” recalled Renie.

Philip’s doctor referred them to a phase I clinical trial at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, that was testing an experimental targeted therapy called selumetinib. The trial was led by Brigitte Widemann, M.D., chief of NCI’s Pediatric Oncology Branch, and involved collaborators from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, and the Children’s National Health System.

Laboratory researchers had previously shown that mutations in the NF1 gene cause neurofibromas to grow through a chemical pathway inside cells called the RAS pathway. Selumetinib blocks a specific node in this pathway called MEK. In mouse models of NF1, MEK inhibitors reduced the growth of neurofibroma tumors. Other MEK inhibitors are safe and effective in other types of adult cancers. Based on these findings, researchers hypothesized that selumetinib might work in NF1 tumors in children.

In September 2015, Philip visited NCI for an intense medical evaluation, joined the trial, and began taking selumetinib twice a day. Because the drug is provided in pill form, Philip was able to return home for ongoing treatment and was monitored by his local pediatrician. He and his family learned to cope with the initial side effects of treatment, which included fatigue, headaches, and nausea. One year after joining the trial, Philip’s tumors were 36% smaller.

Although this trial was a small early-phase study, Philip was among the 71% of children whose tumor volumes decreased by more than 20%. “We saw tumor shrinkage in nearly every patient,” Brigitte remarked. “The shrinkage was measurable…something we had never seen before” among NF1 patients. These promising results are now being pursued in a phase II study.

Philip remains in the trial, and the tumor on his neck has shrunk by half. “Kids don’t ask what’s wrong with him anymore,” said Renie. “It’s meant the world to him and to our family.” Renie acknowledged the years of research that led to this trial. “Someone was planting the seeds in NF1 research so we would benefit from that work now.”

This story was originally published in the NCI Fiscal Year 2019 Annual Plan & Budget Proposal. Read the most recent Annual Plan & Budget Proposal at plan.cancer.gov.