Colon Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version

General Information About Colon Cancer

Cancer of the colon is a highly treatable and often curable disease when localized to the bowel. Surgery is the primary form of treatment and results in cure in approximately 50% of patients. However, recurrence following surgery is a major problem and is often the ultimate cause of death.

Incidence and Mortality

Worldwide, colorectal cancer is the third most common form of cancer. In 2022, there were an estimated 1.93 million new cases of colorectal cancer and 903,859 deaths.[1]

Estimated new cases and deaths from colon and rectal cancer in the United States in 2025:[2]

- New cases of colon cancer: 107,320.

- New cases of rectal cancer: 46,950.

- Deaths: 52,900 (colon and rectal cancers combined).

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors can occur in the colon. For more information, see Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors Treatment.

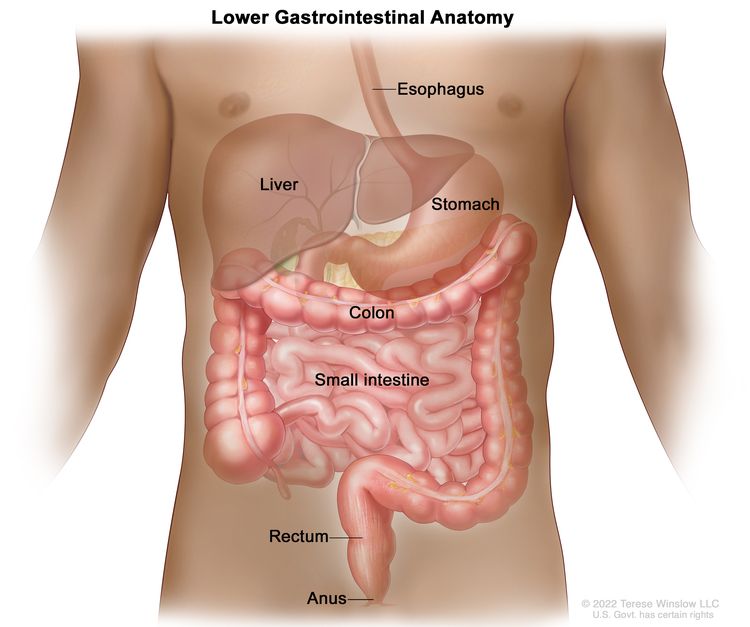

Anatomy

Risk Factors

Increasing age is the most important risk factor for most cancers. Other risk factors for colorectal cancer include the following:

- Family history of colorectal cancer in a first-degree relative.[3]

- Personal history of colorectal adenomas, colorectal cancer, or ovarian cancer.[4-6]

- Hereditary conditions, including familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and Lynch syndrome (hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer [HNPCC]).[7]

- Personal history of long-standing chronic ulcerative colitis or Crohn colitis.[8]

- Excessive alcohol use.[9]

- Cigarette smoking.[10]

- Race and ethnicity: African American.[11,12]

- Obesity.[13]

Screening

Screening for colon cancer should be a part of routine care for all adults aged 50 years and older, especially for those with first-degree relatives with colorectal cancer. This recommendation is based on the frequency of the disease, ability to identify high-risk groups, slow growth of primary lesions, better survival of patients with early-stage lesions, and relative simplicity and accuracy of screening tests. For more information, see Colorectal Cancer Screening.

Prognostic Factors

The prognosis of patients with colon cancer is clearly related to:

- The degree of penetration of the tumor through the bowel wall.

- The presence or absence of nodal involvement.

- The presence or absence of distant metastases.

These three characteristics form the basis for all staging systems developed for this disease.

Other prognostic factors for colon cancer include:

Many other prognostic markers have been evaluated retrospectively for patients with colon cancer, though most, including allelic loss of chromosome 18q or thymidylate synthase expression, have not been prospectively validated.[16-25] Microsatellite instability, also associated with HNPCC, has been associated with improved survival independent of tumor stage in a population-based series of 607 patients younger than 50 years with colorectal cancer.[26] Patients with HNPCC reportedly have better prognoses in stage-stratified survival analysis than patients with sporadic colorectal cancer, but the retrospective nature of the studies and possibility of selection factors make this observation difficult to interpret.[27]

Treatment decisions depend on factors such as physician and patient preferences and the stage of the disease, rather than the age of the patient.[28-30]

Racial differences in overall survival (OS) after adjuvant therapy have been observed, without differences in disease-free survival, suggesting that comorbid conditions play a role in survival outcome in different patient populations.[31]

Follow-Up and Survivorship

Limited data and no high-level evidence are available to guide patients and physicians about surveillance and management of patients after surgical resection and adjuvant therapy. The American Society of Clinical Oncology and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend specific surveillance and follow-up strategies.[32,33]

Following treatment of colon cancer, periodic evaluations may lead to the earlier identification and management of recurrent disease.[34-37] This monitoring has limited effect on overall mortality, as few localized, potentially curable metastases are found in patients with recurrent colon cancer. To date, no large-scale randomized trials have documented an OS benefit for standard, postoperative monitoring programs.[38-42]

CEA is a serum glycoprotein frequently used in the management of patients with colon cancer. A review of the use of this tumor marker suggests:[43]

- A CEA level is not a valuable screening test for colorectal cancer because of the large number of false-positive and false-negative reports.

- Postoperative CEA testing should be restricted to patients who would be candidates for resection of liver or lung metastases.

- Routine use of CEA levels alone for monitoring response to treatment is not recommended.

The optimal regimen and frequency of follow-up examinations are not well defined because the impact on patient survival is not clear and the quality of data is poor.[40-42]

Factors Associated With Recurrence

Diet and exercise

Although cohort studies have suggested that a diet or exercise regimen may improve outcomes, no prospective randomized trials have confirmed these findings. The cohort studies contained multiple opportunities for unintended bias, and caution is needed when using the data from them.

Two prospective observational studies were performed with patients enrolled in the Cancer and Leukemia Group B CALGB-89803 trial (NCT00003835), an adjuvant chemotherapy trial for patients with stage III colon cancer.[44,45] In this trial, patients in the lowest quintile of the Western dietary pattern, compared with those patients in the highest quintile, experienced an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for disease-free survival of 3.25 (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.04–5.19; P < .001) and an OS of 2.32 (95% CI, 1.36–3.96; P < .001). Additionally, stage III colon cancer patients in the highest quintile of dietary glycemic load experienced an adjusted HR for OS of 1.76 (95% CI, 1.22–2.54; P < .001), compared with those in the lowest quintile. Subsequently, in the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort, among 2,315 participants diagnosed with colorectal cancer, the degree of red and processed meat intake before diagnosis was associated with a higher risk of death (relative risk [RR], 1.29; 95% CI, 1.05–1.59; P = .03), but red meat consumption after diagnosis was not associated with overall mortality.[46][Level of evidence C1]

A meta-analysis of seven prospective cohort studies evaluating physical activity before and after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer demonstrated that patients who participated in any amount of physical activity before diagnosis had an RR of 0.75 (95% CI, 0.65–0.87; P < .001) for colorectal cancer-specific mortality, compared with patients who did not participate in any physical activity.[47] Patients who participated in a high amount of physical activity (vs. a low amount) before diagnosis had an RR of 0.70 (95% CI, 0.56–0.87; P = .002). Patients who participated in any physical activity (compared with no activity) after diagnosis had an RR of 0.74 (95% CI, 0.58–0.95; P = .02) for colorectal cancer-specific mortality. Those who participated in a high amount of physical activity (vs. a low amount) after diagnosis had an RR of 0.65 (95% CI, 0.47–0.92; P = .01).[47][Level of evidence C1]

Aspirin

A prospective cohort study examined the use of aspirin after a colorectal cancer diagnosis.[48] Regular users of aspirin after a diagnosis of colorectal cancer experienced an HRcolon cancer–specific mortality of 0.71 (95% CI, 0.53–0.95) and an HRoverall mortality of 0.79 (95% CI, 0.65–0.97).[48][Level of evidence C1] One study evaluated 964 patients with rectal or colon cancer from the Nurse’s Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study.[49] Among patients with colorectal cancer and PI3K variants, regular use of aspirin was associated with an HRdeath from any cause of 0.54 (95% CI, 0.31–0.94; P = .01)[49][Level of evidence C1]

References

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al.: Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 74 (3): 229-263, 2024. [PUBMED Abstract]

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2025. American Cancer Society, 2025. Available online. Last accessed January 16, 2025.

- Johns LE, Houlston RS: A systematic review and meta-analysis of familial colorectal cancer risk. Am J Gastroenterol 96 (10): 2992-3003, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Imperiale TF, Juluri R, Sherer EA, et al.: A risk index for advanced neoplasia on the second surveillance colonoscopy in patients with previous adenomatous polyps. Gastrointest Endosc 80 (3): 471-8, 2014. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Singh H, Nugent Z, Demers A, et al.: Risk of colorectal cancer after diagnosis of endometrial cancer: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol 31 (16): 2010-5, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Srinivasan R, Yang YX, Rubin SC, et al.: Risk of colorectal cancer in women with a prior diagnosis of gynecologic malignancy. J Clin Gastroenterol 41 (3): 291-6, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mork ME, You YN, Ying J, et al.: High Prevalence of Hereditary Cancer Syndromes in Adolescents and Young Adults With Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol 33 (31): 3544-9, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Laukoetter MG, Mennigen R, Hannig CM, et al.: Intestinal cancer risk in Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 15 (4): 576-83, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Fedirko V, Tramacere I, Bagnardi V, et al.: Alcohol drinking and colorectal cancer risk: an overall and dose-response meta-analysis of published studies. Ann Oncol 22 (9): 1958-72, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Liang PS, Chen TY, Giovannucci E: Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cancer 124 (10): 2406-15, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Laiyemo AO, Doubeni C, Pinsky PF, et al.: Race and colorectal cancer disparities: health-care utilization vs different cancer susceptibilities. J Natl Cancer Inst 102 (8): 538-46, 2010. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Kuntz KM, Knudsen AB, et al.: Contribution of screening and survival differences to racial disparities in colorectal cancer rates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 21 (5): 728-36, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Ma Y, Yang Y, Wang F, et al.: Obesity and risk of colorectal cancer: a systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS One 8 (1): e53916, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Steinberg SM, Barkin JS, Kaplan RS, et al.: Prognostic indicators of colon tumors. The Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group experience. Cancer 57 (9): 1866-70, 1986. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Filella X, Molina R, Grau JJ, et al.: Prognostic value of CA 19.9 levels in colorectal cancer. Ann Surg 216 (1): 55-9, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- McLeod HL, Murray GI: Tumour markers of prognosis in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 79 (2): 191-203, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jen J, Kim H, Piantadosi S, et al.: Allelic loss of chromosome 18q and prognosis in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 331 (4): 213-21, 1994. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lanza G, Matteuzzi M, Gafá R, et al.: Chromosome 18q allelic loss and prognosis in stage II and III colon cancer. Int J Cancer 79 (4): 390-5, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Griffin MR, Bergstralh EJ, Coffey RJ, et al.: Predictors of survival after curative resection of carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Cancer 60 (9): 2318-24, 1987. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Johnston PG, Fisher ER, Rockette HE, et al.: The role of thymidylate synthase expression in prognosis and outcome of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 12 (12): 2640-7, 1994. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Shibata D, Reale MA, Lavin P, et al.: The DCC protein and prognosis in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 335 (23): 1727-32, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bauer KD, Lincoln ST, Vera-Roman JM, et al.: Prognostic implications of proliferative activity and DNA aneuploidy in colonic adenocarcinomas. Lab Invest 57 (3): 329-35, 1987. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bauer KD, Bagwell CB, Giaretti W, et al.: Consensus review of the clinical utility of DNA flow cytometry in colorectal cancer. Cytometry 14 (5): 486-91, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sun XF, Carstensen JM, Zhang H, et al.: Prognostic significance of cytoplasmic p53 oncoprotein in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Lancet 340 (8832): 1369-73, 1992. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Roth JA: p53 prognostication: paradigm or paradox? Clin Cancer Res 5 (11): 3345, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gryfe R, Kim H, Hsieh ET, et al.: Tumor microsatellite instability and clinical outcome in young patients with colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 342 (2): 69-77, 2000. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Watson P, Lin KM, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, et al.: Colorectal carcinoma survival among hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma family members. Cancer 83 (2): 259-66, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Iwashyna TJ, Lamont EB: Effectiveness of adjuvant fluorouracil in clinical practice: a population-based cohort study of elderly patients with stage III colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 20 (19): 3992-8, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Chiara S, Nobile MT, Vincenti M, et al.: Advanced colorectal cancer in the elderly: results of consecutive trials with 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 42 (4): 336-40, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Popescu RA, Norman A, Ross PJ, et al.: Adjuvant or palliative chemotherapy for colorectal cancer in patients 70 years or older. J Clin Oncol 17 (8): 2412-8, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Dignam JJ, Colangelo L, Tian W, et al.: Outcomes among African-Americans and Caucasians in colon cancer adjuvant therapy trials: findings from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project. J Natl Cancer Inst 91 (22): 1933-40, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Meyerhardt JA, Mangu PB, Flynn PJ, et al.: Follow-up care, surveillance protocol, and secondary prevention measures for survivors of colorectal cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline endorsement. J Clin Oncol 31 (35): 4465-70, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Benson AB, Bekaii-Saab T, Chan E, et al.: Localized colon cancer, version 3.2013: featured updates to the NCCN Guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 11 (5): 519-28, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Martin EW, Minton JP, Carey LC: CEA-directed second-look surgery in the asymptomatic patient after primary resection of colorectal carcinoma. Ann Surg 202 (3): 310-7, 1985. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bruinvels DJ, Stiggelbout AM, Kievit J, et al.: Follow-up of patients with colorectal cancer. A meta-analysis. Ann Surg 219 (2): 174-82, 1994. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lautenbach E, Forde KA, Neugut AI: Benefits of colonoscopic surveillance after curative resection of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg 220 (2): 206-11, 1994. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Khoury DA, Opelka FG, Beck DE, et al.: Colon surveillance after colorectal cancer surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 39 (3): 252-6, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Safi F, Link KH, Beger HG: Is follow-up of colorectal cancer patients worthwhile? Dis Colon Rectum 36 (7): 636-43; discussion 643-4, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Macdonald JS, et al.: An evaluation of the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) test for monitoring patients with resected colon cancer. JAMA 270 (8): 943-7, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Rosen M, Chan L, Beart RW, et al.: Follow-up of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum 41 (9): 1116-26, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Desch CE, Benson AB, Smith TJ, et al.: Recommended colorectal cancer surveillance guidelines by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 17 (4): 1312, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Benson AB, Desch CE, Flynn PJ, et al.: 2000 update of American Society of Clinical Oncology colorectal cancer surveillance guidelines. J Clin Oncol 18 (20): 3586-8, 2000. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Clinical practice guidelines for the use of tumor markers in breast and colorectal cancer. Adopted on May 17, 1996 by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 14 (10): 2843-77, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Meyerhardt JA, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al.: Association of dietary patterns with cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer. JAMA 298 (7): 754-64, 2007. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Meyerhardt JA, Sato K, Niedzwiecki D, et al.: Dietary glycemic load and cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: findings from CALGB 89803. J Natl Cancer Inst 104 (22): 1702-11, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

- McCullough ML, Gapstur SM, Shah R, et al.: Association between red and processed meat intake and mortality among colorectal cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 31 (22): 2773-82, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Je Y, Jeon JY, Giovannucci EL, et al.: Association between physical activity and mortality in colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Int J Cancer 133 (8): 1905-13, 2013. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Chan AT, Ogino S, Fuchs CS: Aspirin use and survival after diagnosis of colorectal cancer. JAMA 302 (6): 649-58, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Liao X, Lochhead P, Nishihara R, et al.: Aspirin use, tumor PIK3CA mutation, and colorectal-cancer survival. N Engl J Med 367 (17): 1596-606, 2012. [PUBMED Abstract]

Cellular Classification of Colon Cancer

Histological types of colon cancer include:

- Adenocarcinoma (most colon cancers).

- Mucinous (colloid) adenocarcinoma.

- Signet ring adenocarcinoma.

- Scirrhous tumors.

- Neuroendocrine.[1] Tumors with neuroendocrine differentiation typically have a poorer prognosis than pure adenocarcinoma variants.

References

- Saclarides TJ, Szeluga D, Staren ED: Neuroendocrine cancers of the colon and rectum. Results of a ten-year experience. Dis Colon Rectum 37 (7): 635-42, 1994. [PUBMED Abstract]

Stage Information for Colon Cancer

Treatment decisions can be made with reference to the TNM (tumor, node, metastasis) classification [1] rather than to the older Dukes or the Modified Astler-Coller classification schema.

The AJCC and a National Cancer Institute–sponsored panel recommended that at least 12 lymph nodes be examined in patients with colon and rectal cancer to confirm the absence of nodal involvement by tumor.[1-3] This recommendation takes into consideration that the number of lymph nodes examined is a reflection of the aggressiveness of lymphovascular mesenteric dissection at the time of surgical resection and the pathological identification of nodes in the specimen. Retrospective studies demonstrated that the number of lymph nodes examined in colon and rectal surgery may be associated with patient outcome.[4-7]

AJCC Stage Groupings and TNM Definitions

The AJCC has designated staging by TNM classification to define colon cancer.[1] The same classification is used for both clinical and pathological staging.[1]

| Stage | TNMb,c | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph nodes; M = distant metastasis. | |||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Colon and rectum. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp 251–74. | |||

| The explanations for superscripts b and c are at the end of Table 5. | |||

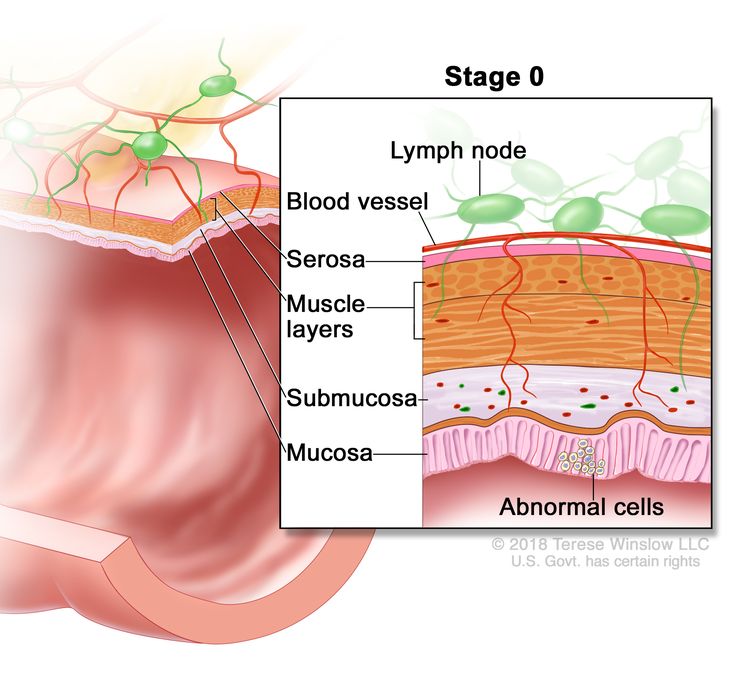

| 0 | Tis, N0, M0 | Tis = Carcinoma in situ, intramucosal carcinoma (involvement of lamina propria with no extension through muscularis mucosae). |

|

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis by imaging, etc.; no evidence of tumor in distant sites or organs. (This category is not assigned by pathologists.) | |||

| Stage | TNMb,c | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph nodes; M = distant metastasis. | |||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Colon and rectum. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp 251–74. | |||

| The explanations for superscripts b and c are at the end of Table 5. | |||

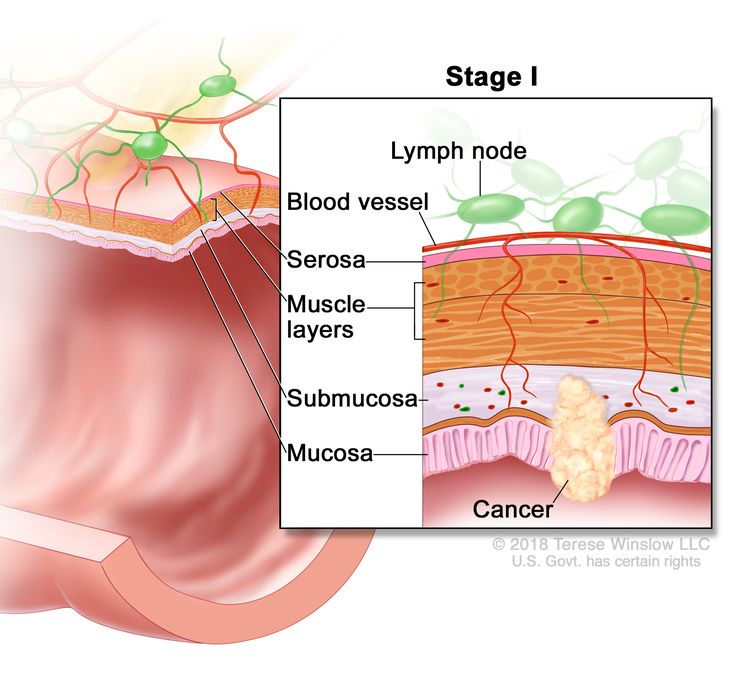

| I | T1, T2, N0, M0 | T1 = Tumor invades the submucosa (through the muscularis mucosa but not into the muscularis propria). |

|

| T2 = Tumor invades the muscularis propria. | |||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis by imaging, etc.; no evidence of tumor in distant sites or organs. (This category is not assigned by pathologists.) | |||

| Stage | TNMb,c | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph nodes; M = distant metastasis. | |||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Colon and rectum. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp 251–74. | |||

| The explanations for superscripts b and c are at the end of Table 5. | |||

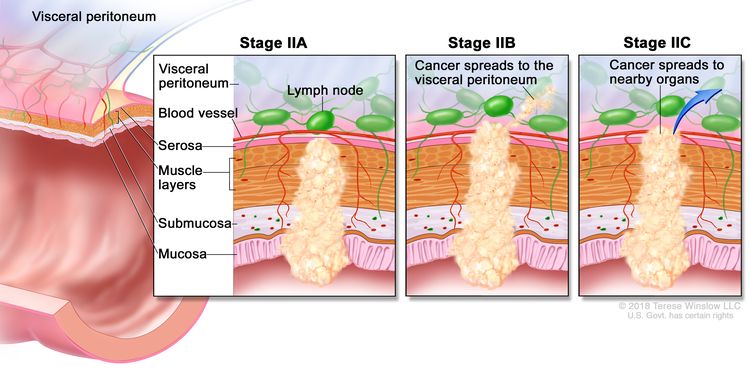

| IIA | T3, N0, M0 | T3 = Tumor invades through the muscularis propria into pericolorectal tissues. |

|

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis by imaging, etc.; no evidence of tumor in distant sites or organs. (This category is not assigned by pathologists.) | |||

| IIB | T4a, N0, M0 | T4a = Tumor invades through the visceral peritoneum (including gross perforation of the bowel through tumor and continuous invasion of tumor through areas of inflammation to the surface of the visceral peritoneum). | |

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis by imaging, etc.; no evidence of tumor in distant sites or organs. (This category is not assigned by pathologists.) | |||

| IIC | T4b, N0, M0 | T4b = Tumor directly invades or adheres to adjacent organs or structures. | |

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis by imaging, etc.; no evidence of tumor in distant sites or organs. (This category is not assigned by pathologists.) | |||

| Stage | TNMb,c | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph nodes; M = distant metastasis. | |||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Colon and rectum. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp 251–74. | |||

| The explanations for superscripts b and c are at the end of Table 5. | |||

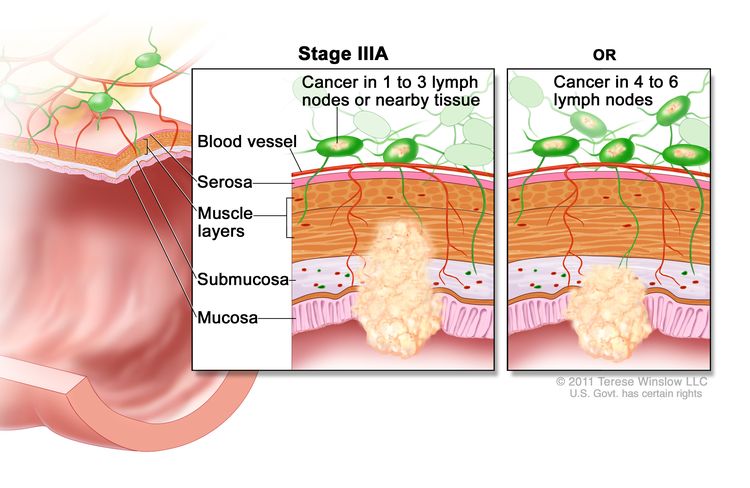

| IIIA | T1, N2a, M0 | T1 = Tumor invades the submucosa (through the muscularis mucosa but not into the muscularis propria). |

|

| N2a = Four to six regional lymph nodes are positive. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis by imaging, etc.; no evidence of tumor in distant sites or organs. (This category is not assigned by pathologists.) | |||

| T1–2, N1/N1c, M0 | T1 = Tumor invades the submucosa (through the muscularis mucosa but not into the muscularis propria). | ||

| T2 = Tumor invades the muscularis propria. | |||

| N1 = One to three regional lymph nodes are positive (tumor in lymph nodes measuring ≥0.2 mm), or any number of tumor deposits are present and all identifiable lymph nodes are negative. | |||

| –N1c = No regional lymph nodes are positive, but there are tumor deposits in the subserosa, mesentery, or nonperitonealized pericolic, or perirectal/mesorectal tissues. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis by imaging, etc.; no evidence of tumor in distant sites or organs. (This category is not assigned by pathologists.) | |||

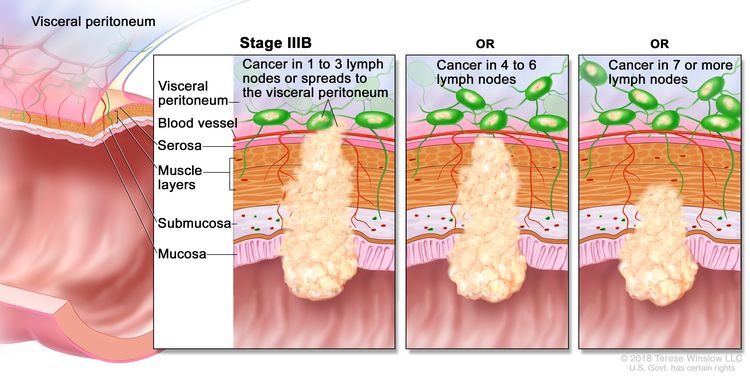

| IIIB | T1–T2, N2b, M0 | T1 = Tumor invades the submucosa (through the muscularis mucosa but not into the muscularis propria). |

|

| T2 = Tumor invades the muscularis propria. | |||

| N2b = Seven or more regional lymph nodes are positive. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis by imaging, etc.; no evidence of tumor in distant sites or organs. (This category is not assigned by pathologists.) | |||

| T2–T3, N2a, M0 | T2 = Tumor invades the muscularis propria. | ||

| T3 = Tumor invades through the muscularis propria into pericolorectal tissues. | |||

| N2a = Four to six regional lymph nodes are positive. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis by imaging, etc.; no evidence of tumor in distant sites or organs. (This category is not assigned by pathologists.) | |||

| T3–T4a, N1/N1c, M0 | T3 = Tumor invades through the muscularis propria into pericolorectal tissues. | ||

| T4 = Tumor invades the visceral peritoneum or invades or adheres to adjacent organ or structure. | |||

| –T4a = Tumor invades through the visceral peritoneum (including gross perforation of the bowel through tumor and continuous invasion of tumor through areas of inflammation to the surface of the visceral peritoneum). | |||

| N1 = One to three regional lymph nodes are positive (tumor in lymph nodes measuring ≥0.2 mm), or any number of tumor deposits are present and all identifiable lymph nodes are negative. | |||

| –N1c = No regional lymph nodes are positive, but there are tumor deposits in the subserosa, mesentery, or nonperitonealized pericolic, or perirectal/mesorectal tissues. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis by imaging, etc.; no evidence of tumor in distant sites or organs. (This category is not assigned by pathologists.) | |||

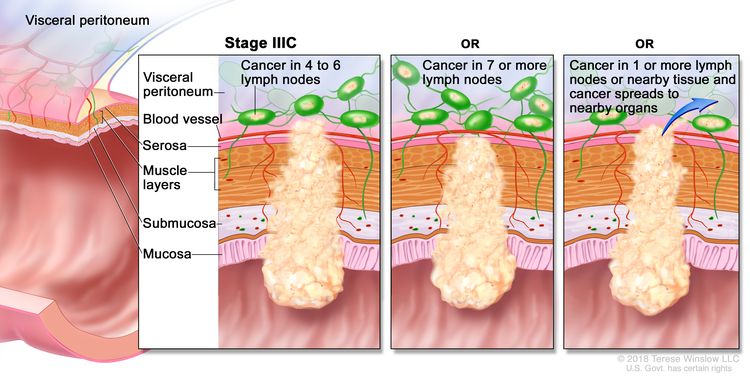

| IIIC | T3–T4a, N2b, M0 | T3 = Tumor invades through the muscularis propria into pericolorectal tissues. |

|

| T4 = Tumor invades the visceral peritoneum or invades or adheres to adjacent organ or structure. | |||

| –T4a = Tumor invades through the visceral peritoneum (including gross perforation of the bowel through tumor and continuous invasion of tumor through areas of inflammation to the surface of the visceral peritoneum). | |||

| N2b = Seven or more regional lymph nodes are positive. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis by imaging, etc.; no evidence of tumor in distant sites or organs. (This category is not assigned by pathologists.) | |||

| T4a, N2a, M0 | T4a = Tumor invades through the visceral peritoneum (including gross perforation of the bowel through tumor and continuous invasion of tumor through areas of inflammation to the surface of the visceral peritoneum). | ||

| N2a = Four to six regional lymph nodes are positive. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis by imaging, etc.; no evidence of tumor in distant sites or organs. (This category is not assigned by pathologists.) | |||

| T4b, N1–N2, M0 | T4b = Tumor directly invades or adheres to adjacent organs or structures. | ||

| N1 = One to three regional lymph nodes are positive (tumor in lymph nodes measuring ≥0.2 mm), or any number of tumor deposits are present and all identifiable lymph nodes are negative. | |||

| –N1a = One regional lymph node is positive. | |||

| –N1b = Two or three regional lymph nodes are positive. | |||

| –N1c = No regional lymph nodes are positive, but there are tumor deposits in the subserosa, mesentery, or nonperitonealized pericolic, or perirectal/mesorectal tissues. | |||

| N2 = Four or more regional nodes are positive. | |||

| –N2a = Four to six regional lymph nodes are positive. | |||

| –N2b = Seven or more regional lymph nodes are positive. | |||

| M0 = No distant metastasis by imaging, etc.; no evidence of tumor in distant sites or organs. (This category is not assigned by pathologists.) | |||

| Stage | TNMb,c | Definition | Illustration |

|---|---|---|---|

| T = primary tumor; N = regional lymph nodes; M = distant metastasis. | |||

| aReprinted with permission from AJCC: Colon and rectum. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2017, pp 251–74. | |||

| bDirect invasion in T4 includes invasion of other organs or other segments of the colorectum as a result of direct extension through the serosa, as confirmed on microscopic examination (e.g., invasion of the sigmoid colon by a carcinoma of the cecum) or, for cancers in a retroperitoneal or subperitoneal location, direct invasion of other organs or structures by virtue of extension beyond the muscularis propria (i.e., respectively, a tumor on the posterior wall of the descending colon invading the left kidney or lateral abdominal wall; or a mid or distal rectal cancer with invasion of prostate, seminal vesicles, cervix, or vagina). | |||

| cTumor that is adherent to other organs or structures, grossly, is classified cT4b. However, if no tumor is present in the adhesion, microscopically, the classification should be pT1-4a depending on the anatomical depth of wall invasion. The V and L classification should be used to identify the presence or absence of vascular or lymphatic invasion whereas the PN prognostic factor should be used for perineural invasion. | |||

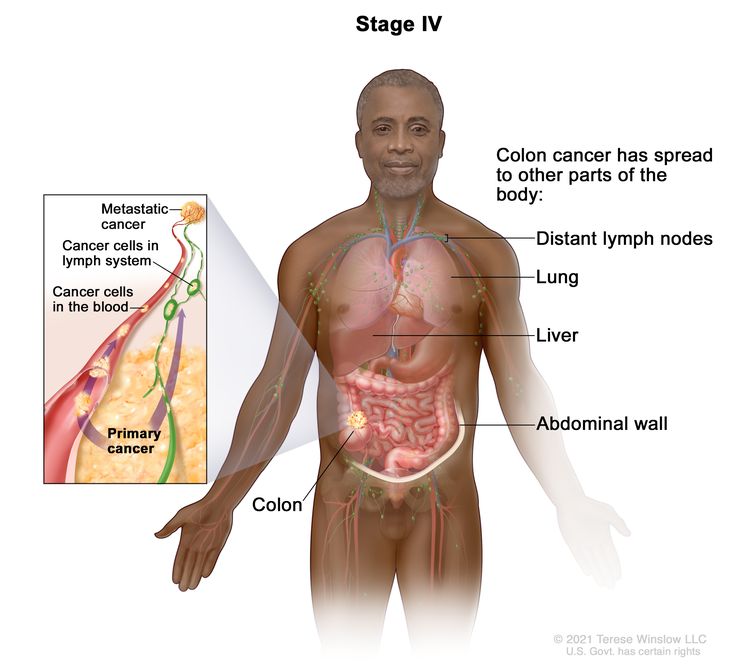

| IVA | Any T, Any N, M1a | TX = Primary tumor cannot be assessed. |

|

| T0 = No evidence of primary tumor. | |||

| Tis = Carcinoma in situ, intramucosal carcinoma (involvement of lamina propria with no extension through muscularis mucosae). | |||

| T1 = Tumor invades the submucosa (through the muscularis mucosa but not into the muscularis propria). | |||

| T2 = Tumor invades the muscularis propria. | |||

| T3 = Tumor invades through the muscularis propria into pericolorectal tissues. | |||

| T4 = Tumor invades the visceral peritoneum or invades or adheres to adjacent organ or structure. | |||

| –T4a = Tumor invades through the visceral peritoneum (including gross perforation of the bowel through tumor and continuous invasion of tumor through areas of inflammation to the surface of the visceral peritoneum). | |||

| –T4b = Tumor directly invades or adheres to adjacent organs or structures. | |||

| NX = Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed. | |||

| N0 = No regional lymph node metastasis. | |||

| N1 = One to three regional lymph nodes are positive (tumor in lymph nodes measuring ≥0.2 mm), or any number of tumor deposits are present and all identifiable lymph nodes are negative. | |||

| –N1a = One regional lymph node is positive. | |||

| –N1b = Two or three regional lymph nodes are positive. | |||

| –N1c = No regional lymph nodes are positive, but there are tumor deposits in the subserosa, mesentery, or nonperitonealized pericolic, or perirectal/mesorectal tissues. | |||

| N2 = Four or more regional nodes are positive. | |||

| –N2a = Four to six regional lymph nodes are positive. | |||

| –N2b = Seven or more regional lymph nodes are positive. | |||

| M1a = Metastasis to one site or organ is identified without peritoneal metastasis. | |||

| IVB | Any T, Any N, M1b | Any T = See T descriptions above in Any T, Any N, M1a TNM stage group. | |

| Any N = See N descriptions above in Any T, Any N1, M1a TNM stage group. | |||

| M1b = Metastasis to two or more sites or organs is identified without peritoneal metastasis. | |||

| IVC | Any T, Any N, M1c | Any T = See T descriptions above in Any T, Any N, M1a TNM stage group. | |

| Any N = See N descriptions above in Any T, Any N1, M1a TNM stage group. | |||

| M1c = Metastasis to the peritoneal surface is identified alone or with other site or organ metastases. | |||

References

- Jessup J, Benson A, Chen V: Colon and Rectum. In: Amin MB, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al., eds.: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Springer; 2017, pp 251–74.

- Compton CC, Greene FL: The staging of colorectal cancer: 2004 and beyond. CA Cancer J Clin 54 (6): 295-308, 2004 Nov-Dec. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Nelson H, Petrelli N, Carlin A, et al.: Guidelines 2000 for colon and rectal cancer surgery. J Natl Cancer Inst 93 (8): 583-96, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Swanson RS, Compton CC, Stewart AK, et al.: The prognosis of T3N0 colon cancer is dependent on the number of lymph nodes examined. Ann Surg Oncol 10 (1): 65-71, 2003 Jan-Feb. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Le Voyer TE, Sigurdson ER, Hanlon AL, et al.: Colon cancer survival is associated with increasing number of lymph nodes analyzed: a secondary survey of intergroup trial INT-0089. J Clin Oncol 21 (15): 2912-9, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Prandi M, Lionetto R, Bini A, et al.: Prognostic evaluation of stage B colon cancer patients is improved by an adequate lymphadenectomy: results of a secondary analysis of a large scale adjuvant trial. Ann Surg 235 (4): 458-63, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Tepper JE, O'Connell MJ, Niedzwiecki D, et al.: Impact of number of nodes retrieved on outcome in patients with rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 19 (1): 157-63, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment Option Overview for Colon Cancer

| Stage (TNM Staging Criteria) | Treatment Options |

|---|---|

| Stage 0 Colon Cancer | Surgery |

| Stage I Colon Cancer | Surgery |

| Stage II Colon Cancer | Surgery |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (under clinical evaluation) | |

| Stage III Colon Cancer | Surgery |

| Clinical trials | |

| Liver Metastasis | Surgery |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | |

| Local ablation | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | |

| Intra-arterial chemotherapy | |

| Clinical trials | |

| Stage IV and Recurrent Colon Cancer | Surgery |

| Systemic therapy | |

| Immunotherapy | |

| Clinical trials |

Primary Surgical Therapy

Standard treatment for patients with colon cancer has been open surgical resection of the primary and regional lymph nodes for localized disease.

The role of laparoscopic techniques [1-4] in the treatment of colon cancer has been examined in two studies.

Evidence (laparoscopic techniques):

- A multicenter, prospective, randomized, noninferiority trial (NCCTG-934653 [NCT00002575]) compared laparoscopic-assisted colectomy (LAC) with open colectomy in 872 patients.

- At a median follow-up of 4.4 years, 3-year recurrence rates (16% LAC vs. 18% open colectomy; hazard ratio [HR] for recurrence, 0.86; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.63–1.17; P = .32) and 3-year overall survival (OS) rates (86% LAC vs. 85% open colectomy; HRdeath in LAC, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.68–1.21; P = .51) were similar in both groups for all stages of disease evaluated. Tumor recurrence in surgical incisions was less than 1% for both groups.[5][Level of evidence A1]

- Decreased hospital stay (5 days LAC vs. 6 days open colectomy, P < .001) and decreased use of analgesics were reported in the LAC group. A 21% conversion rate from LAC to open procedure was shown.

- This study excluded patients with locally advanced disease, transverse colon and rectal tumor locations, and perforated lesions. Each of the 66 surgeons participating in the trial had performed at least 20 LACs and were accredited for study participation after independent videotape review assured appropriate oncologic and surgical principles were maintained.[5] The quality-of-life component of this trial was published separately and minimal short-term quality-of-life benefits with LAC were reported.[6][Level of evidence A3]

- One small, single-institution randomized study of 219 patients showed that the LAC procedure was independently associated with reduced tumor recurrence on multivariate analysis.[7][Level of evidence A1]

Surgery is curative in 25% to 40% of highly selected patients who develop resectable metastases in the liver and lung. Improved surgical techniques and advances in preoperative imaging have allowed for better patient selection for resection.

Adjuvant Chemotherapy

The potential value of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage II colon cancer is controversial. Pooled analyses and meta-analyses have suggested a 2% to 4% improvement in OS for patients treated with adjuvant fluorouracil (5-FU)–based therapy compared with observation.[8-10] For more information, see the Treatment of Stage II Colon Cancer section.

Before 2000, 5-FU was the only useful cytotoxic chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting for patients with stage III colon cancer. Since 2000, capecitabine has been established as an equivalent alternative to 5-FU and leucovorin (5-FU/LV). The addition of oxaliplatin to 5-FU/LV has been shown to improve OS compared with 5-FU/LV alone. For more information, see the Treatment of Stage III Colon Cancer section.

Chemotherapy regimens

Table 7 describes the chemotherapy regimens used to treat colon cancer.

| Regimen Name | Drug Combination | Dose |

|---|---|---|

| 5-FU = fluorouracil; AIO = Arbeitsgemeinschaft Internistische Onkologie; bid = twice a day; IV = intravenous; LV = leucovorin. | ||

| AIO or German AIO | Folic acid, 5-FU, and irinotecan | Irinotecan (100 mg/m2) and LV (500 mg/m2) administered as 2-hour infusions on d 1, followed by 5-FU (2,000 mg/m2) IV bolus administered via ambulatory pump weekly over 24 h, 4 times a y (52 wk). |

| CAPOX | Capecitabine and oxaliplatin | Capecitabine (1,000 mg/m2) bid on d 1–14, plus oxaliplatin (70 mg/m2) on d 1 and 8 every 3 wk. |

| Douillard | Folic acid, 5-FU, and irinotecan | Irinotecan (180 mg/m2) administered as a 2-h infusion on d 1, LV (200 mg/m2) administered as a 2-h infusion on d 1 and 2, followed by a loading dose of 5-FU (400 mg/m2) IV bolus, then 5-FU (600 mg/m2) administered via ambulatory pump over 22 h every 2 wk on d 1 and 2. |

| FOLFIRI | LV, 5-FU, and irinotecan | Irinotecan (180 mg/m2) and LV (400 mg/m2) administered as 2-h infusions on d 1, followed by a loading dose of 5-FU (400 mg/m2) IV bolus administered on d 1, then 5-FU (2,400–3,000 mg/m2) administered via ambulatory pump over 46 h every 2 wk. |

| FOLFOX-4 | Oxaliplatin, LV, and 5-FU | Oxaliplatin (85 mg/m2) administered as a 2-h infusion on d 1, LV (200 mg/m2) administered as a 2-h infusion on d 1 and 2, followed by a loading dose of 5-FU (400 mg/m2) IV bolus, then 5-FU (600 mg/m2) administered via ambulatory pump over 22 h every 2 wk on d 1 and 2. |

| FOLFOX-6 | Oxaliplatin, LV, and 5-FU | Oxaliplatin (85–100 mg/m2) and LV (400 mg/m2) administered as 2-h infusions on d 1, followed by a loading dose of 5-FU (400 mg/m2) IV bolus on d 1, then 5-FU (2,400–3,000 mg/m2) administered via ambulatory pump over 46 h every 2 wk. |

| FOLFOXIRI | Irinotecan, oxaliplatin, LV, 5-FU | Irinotecan (165 mg/m2) administered as a 60-min infusion, then concomitant infusion of oxaliplatin (85 mg/m2) and LV (200 mg/m2) over 120 min, followed by 5-FU (3,200 mg/m2) administered as a 48-h continuous infusion. |

| FUFOX | 5-FU, LV, and oxaliplatin | Oxaliplatin (50 mg/m2) plus LV (500 mg/m2) plus 5-FU (2,000 mg/m2) administered as a 22-h continuous infusion on d 1, 8, 22, and 29 every 36 d. |

| FUOX | 5-FU plus oxaliplatin | 5-FU (2,250 mg/m2) administered as a continuous infusion over 48 h on d 1, 8, 15, 22, 29, and 36 plus oxaliplatin (85 mg/m2) on d 1, 15, and 29 every 6 wk. |

| IFL (or Saltz) | Irinotecan, 5-FU, and LV | Irinotecan (125 mg/m2) plus 5-FU (500 mg/m2) IV bolus and LV (20 mg/m2) IV bolus administered weekly for 4 out of 6 wk. |

| XELOX | Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin | Oral capecitabine (1,000 mg/m2) administered bid for 14 d plus oxaliplatin (130 mg/m2) on d 1 every 3 wk. |

Capecitabine and fluorouracil dosing

The DPYD gene encodes an enzyme that catabolizes pyrimidines and fluoropyrimidines, like capecitabine and fluorouracil. An estimated 1% to 2% of the population has germline pathogenic variants in DPYD, which lead to reduced DPD protein function and an accumulation of pyrimidines and fluoropyrimidines in the body.[11,12] Patients with the DPYD*2A variant who receive fluoropyrimidines may experience severe, life-threatening toxicities that are sometimes fatal. Many other DPYD variants have been identified, with a range of clinical effects.[11-13] Fluoropyrimidine avoidance or a dose reduction of 50% may be recommended based on the patient's DPYD genotype and number of functioning DPYD alleles.[14-16] DPYD genetic testing costs less than $200, but insurance coverage varies due to a lack of national guidelines.[17] In addition, testing may delay therapy by 2 weeks, which would not be advisable in urgent situations. This controversial issue requires further evaluation.[18]

Adjuvant Radiation Therapy

While combined modality therapy with chemotherapy and radiation therapy has a significant role in the management of patients with rectal cancer (below the peritoneal reflection), the role of adjuvant radiation therapy for patients with colon cancer (above the peritoneal reflection) is not well defined. Patterns-of-care analyses and single-institution retrospective reviews suggest a role for radiation therapy in certain high-risk subsets of colon cancer patients (e.g., T4, tumor location in immobile sites, local perforation, obstruction, and residual disease postresection).[19-24]

Evidence (adjuvant radiation therapy):

- A phase III, randomized, intergroup study evaluated the benefit of adding radiation therapy to surgery and chemotherapy with 5-FU-levamisole in selected patients with high-risk colon cancer (e.g., T4; or T3, N1–N2 ascending and/or descending colon).[25]

- This clinical trial closed early secondary to inadequate patient accrual. An analysis of 222 enrolled patients (the original goal was 700 patients) demonstrated no relapse or OS benefit for the group that received radiation therapy, although the sample size and statistical power were inadequate to exclude benefit.

Adjuvant radiation therapy has no current standard role in the management of patients with colon cancer following curative resection, although it may have a role for patients with residual disease.

References

- Bokey EL, Moore JW, Chapuis PH, et al.: Morbidity and mortality following laparoscopic-assisted right hemicolectomy for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 39 (10 Suppl): S24-8, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Franklin ME, Rosenthal D, Abrego-Medina D, et al.: Prospective comparison of open vs. laparoscopic colon surgery for carcinoma. Five-year results. Dis Colon Rectum 39 (10 Suppl): S35-46, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Fleshman JW, Nelson H, Peters WR, et al.: Early results of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer. Retrospective analysis of 372 patients treated by Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy (COST) Study Group. Dis Colon Rectum 39 (10 Suppl): S53-8, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schwenk W, Böhm B, Müller JM: Postoperative pain and fatigue after laparoscopic or conventional colorectal resections. A prospective randomized trial. Surg Endosc 12 (9): 1131-6, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group: A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 350 (20): 2050-9, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Weeks JC, Nelson H, Gelber S, et al.: Short-term quality-of-life outcomes following laparoscopic-assisted colectomy vs open colectomy for colon cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA 287 (3): 321-8, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lacy AM, García-Valdecasas JC, Delgado S, et al.: Laparoscopy-assisted colectomy versus open colectomy for treatment of non-metastatic colon cancer: a randomised trial. Lancet 359 (9325): 2224-9, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Efficacy of adjuvant fluorouracil and folinic acid in B2 colon cancer. International Multicentre Pooled Analysis of B2 Colon Cancer Trials (IMPACT B2) Investigators. J Clin Oncol 17 (5): 1356-63, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gill S, Loprinzi CL, Sargent DJ, et al.: Pooled analysis of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy for stage II and III colon cancer: who benefits and by how much? J Clin Oncol 22 (10): 1797-806, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mamounas E, Wieand S, Wolmark N, et al.: Comparative efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with Dukes' B versus Dukes' C colon cancer: results from four National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project adjuvant studies (C-01, C-02, C-03, and C-04) J Clin Oncol 17 (5): 1349-55, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sharma BB, Rai K, Blunt H, et al.: Pathogenic DPYD Variants and Treatment-Related Mortality in Patients Receiving Fluoropyrimidine Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 26 (12): 1008-1016, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lam SW, Guchelaar HJ, Boven E: The role of pharmacogenetics in capecitabine efficacy and toxicity. Cancer Treat Rev 50: 9-22, 2016. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Shakeel F, Fang F, Kwon JW, et al.: Patients carrying DPYD variant alleles have increased risk of severe toxicity and related treatment modifications during fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy. Pharmacogenomics 22 (3): 145-155, 2021. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Amstutz U, Henricks LM, Offer SM, et al.: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for Dihydropyrimidine Dehydrogenase Genotype and Fluoropyrimidine Dosing: 2017 Update. Clin Pharmacol Ther 103 (2): 210-216, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Henricks LM, Lunenburg CATC, de Man FM, et al.: DPYD genotype-guided dose individualisation of fluoropyrimidine therapy in patients with cancer: a prospective safety analysis. Lancet Oncol 19 (11): 1459-1467, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lau-Min KS, Varughese LA, Nelson MN, et al.: Preemptive pharmacogenetic testing to guide chemotherapy dosing in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies: a qualitative study of barriers to implementation. BMC Cancer 22 (1): 47, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Brooks GA, Tapp S, Daly AT, et al.: Cost-effectiveness of DPYD Genotyping Prior to Fluoropyrimidine-based Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Colon Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 21 (3): e189-e195, 2022. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Baker SD, Bates SE, Brooks GA, et al.: DPYD Testing: Time to Put Patient Safety First. J Clin Oncol 41 (15): 2701-2705, 2023. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Willett C, Tepper JE, Cohen A, et al.: Local failure following curative resection of colonic adenocarcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 10 (5): 645-51, 1984. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Willett C, Tepper JE, Cohen A, et al.: Obstructive and perforative colonic carcinoma: patterns of failure. J Clin Oncol 3 (3): 379-84, 1985. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Gunderson LL, Sosin H, Levitt S: Extrapelvic colon--areas of failure in a reoperation series: implications for adjuvant therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 11 (4): 731-41, 1985. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Willett CG, Fung CY, Kaufman DS, et al.: Postoperative radiation therapy for high-risk colon carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 11 (6): 1112-7, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Willett CG, Goldberg S, Shellito PC, et al.: Does postoperative irradiation play a role in the adjuvant therapy of stage T4 colon cancer? Cancer J Sci Am 5 (4): 242-7, 1999 Jul-Aug. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schild SE, Gunderson LL, Haddock MG, et al.: The treatment of locally advanced colon cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 37 (1): 51-8, 1997. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Martenson JA, Willett CG, Sargent DJ, et al.: Phase III study of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy compared with chemotherapy alone in the surgical adjuvant treatment of colon cancer: results of intergroup protocol 0130. J Clin Oncol 22 (16): 3277-83, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Stage 0 Colon Cancer

Stage 0 colon cancer is the most superficial of all the lesions and is limited to the mucosa without invasion of the lamina propria. Because of its superficial nature, the surgical procedure may be limited.

Treatment Options for Stage 0 Colon Cancer

Treatment options for stage 0 colon cancer include:

Surgery

Surgical options include local excision or simple polypectomy with clear margins, or colon resection for larger lesions not amenable to local excision.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

Treatment of Stage I Colon Cancer

Because of its localized nature, stage I colon cancer has a high cure rate.

Treatment Options for Stage I Colon Cancer

Treatment options for stage I colon cancer include:

- Surgery. Wide surgical resection and anastomosis.

Surgery

Evidence (laparoscopic techniques):

- The role of laparoscopic techniques [1-4] in the treatment of colon cancer was examined in a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial (NCCTG-934653 [NCT00002575]) comparing laparoscopic-assisted colectomy (LAC) with open colectomy.

- Three-year recurrence rates and 3-year overall survival rates were similar in the two groups. For more information, see the Primary Surgical Therapy section.

- The quality-of-life component of this trial has been published and minimal short-term quality-of-life benefits with LAC were reported.[5][Level of evidence A3]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Bokey EL, Moore JW, Chapuis PH, et al.: Morbidity and mortality following laparoscopic-assisted right hemicolectomy for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 39 (10 Suppl): S24-8, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Franklin ME, Rosenthal D, Abrego-Medina D, et al.: Prospective comparison of open vs. laparoscopic colon surgery for carcinoma. Five-year results. Dis Colon Rectum 39 (10 Suppl): S35-46, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Fleshman JW, Nelson H, Peters WR, et al.: Early results of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer. Retrospective analysis of 372 patients treated by Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy (COST) Study Group. Dis Colon Rectum 39 (10 Suppl): S53-8, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schwenk W, Böhm B, Müller JM: Postoperative pain and fatigue after laparoscopic or conventional colorectal resections. A prospective randomized trial. Surg Endosc 12 (9): 1131-6, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Weeks JC, Nelson H, Gelber S, et al.: Short-term quality-of-life outcomes following laparoscopic-assisted colectomy vs open colectomy for colon cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA 287 (3): 321-8, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Stage II Colon Cancer

Treatment Options for Stage II Colon Cancer

Treatment options for stage II colon cancer include:

- Surgery. Wide surgical resection and anastomosis.

- Adjuvant chemotherapy (under clinical evaluation).

Surgery

Evidence (laparoscopic techniques):

- The role of laparoscopic techniques [1-4] in the treatment of colon cancer was examined in a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial (NCCTG-934653 [NCT00002575]) comparing laparoscopic-assisted colectomy (LAC) to open colectomy.

- Three-year recurrence rates and 3-year overall survival (OS) rates were similar in the two groups. For more information, see the Primary Surgical Therapy section.

- The quality-of-life component of this trial reported minimal short-term quality-of-life benefits with LAC.[4][Level of evidence A3]

Adjuvant chemotherapy

The potential value of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage II colon cancer remains controversial. Although subgroups of patients with stage II colon cancer may be at higher-than-average risk for recurrence (including those with anatomical features such as tumor adherence to adjacent structures, perforation, and complete obstruction),[5-7] evidence is inconsistent that adjuvant fluorouracil (5-FU)–based chemotherapy is associated with an improved OS compared with surgery alone.[8]

Features in patients with stage II colon cancer that are associated with an increased risk of recurrence include:

- Inadequate lymph node sampling.

- T4 disease.

- Involvement of the visceral peritoneum.

- A poorly differentiated histology.

The decision to use adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage II colon cancer is complicated and requires thoughtful consideration by both patients and their physicians. Adjuvant therapy is not indicated for most patients unless they are entered into a clinical trial.

Evidence (adjuvant chemotherapy):

- The GRECCR-03 (NCT00046995) and NCRI-QUASAR1 (NCT00005586) trials evaluated the use of systemic or regional chemotherapy or biological therapy. Following surgery, patients can be considered for entry into a carefully controlled clinical trial.

- Investigators from the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project have indicated that the reduction in risk of recurrence by adjuvant therapy in patients with stage II disease is of similar magnitude to the benefit seen in patients with stage III disease treated with adjuvant therapy, though an OS advantage has not been established.[9]

- A meta-analysis of 1,000 stage II patients whose experience was amalgamated from a series of trials indicates a 2% advantage in disease-free survival at 5 years when adjuvant therapy–treated patients treated with 5-FU/leucovorin are compared with untreated controls.[10][Level of evidence B1]; [11]

- The Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guideline Initiative Gastrointestinal Cancer Disease Site Group undertook a meta-analysis of the English language–published literature consisting of randomized trials in which adjuvant chemotherapy was compared with observation for patients with stage II colon cancer.

- The mortality risk ratio was 0.87 (95% confidence interval, 0.75–1.01; P = .07).[12]

Based on these data, the American Society of Clinical Oncology issued a guideline stating “direct evidence from randomized controlled trials does not support the routine use of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage II colon cancer.”[13]

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Bokey EL, Moore JW, Chapuis PH, et al.: Morbidity and mortality following laparoscopic-assisted right hemicolectomy for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 39 (10 Suppl): S24-8, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Franklin ME, Rosenthal D, Abrego-Medina D, et al.: Prospective comparison of open vs. laparoscopic colon surgery for carcinoma. Five-year results. Dis Colon Rectum 39 (10 Suppl): S35-46, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Fleshman JW, Nelson H, Peters WR, et al.: Early results of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer. Retrospective analysis of 372 patients treated by Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy (COST) Study Group. Dis Colon Rectum 39 (10 Suppl): S53-8, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Weeks JC, Nelson H, Gelber S, et al.: Short-term quality-of-life outcomes following laparoscopic-assisted colectomy vs open colectomy for colon cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA 287 (3): 321-8, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Lanza G, Matteuzzi M, Gafá R, et al.: Chromosome 18q allelic loss and prognosis in stage II and III colon cancer. Int J Cancer 79 (4): 390-5, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Jen J, Kim H, Piantadosi S, et al.: Allelic loss of chromosome 18q and prognosis in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 331 (4): 213-21, 1994. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Merkel S, Wein A, Günther K, et al.: High-risk groups of patients with Stage II colon carcinoma. Cancer 92 (6): 1435-43, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Macdonald JS, et al.: Intergroup study of fluorouracil plus levamisole as adjuvant therapy for stage II/Dukes' B2 colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 13 (12): 2936-43, 1995. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Mamounas E, Wieand S, Wolmark N, et al.: Comparative efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with Dukes' B versus Dukes' C colon cancer: results from four National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project adjuvant studies (C-01, C-02, C-03, and C-04) J Clin Oncol 17 (5): 1349-55, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Efficacy of adjuvant fluorouracil and folinic acid in B2 colon cancer. International Multicentre Pooled Analysis of B2 Colon Cancer Trials (IMPACT B2) Investigators. J Clin Oncol 17 (5): 1356-63, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Harrington DP: The tea leaves of small trials. J Clin Oncol 17 (5): 1336-8, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Figueredo A, Charette ML, Maroun J, et al.: Adjuvant therapy for stage II colon cancer: a systematic review from the Cancer Care Ontario Program in evidence-based care's gastrointestinal cancer disease site group. J Clin Oncol 22 (16): 3395-407, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Benson AB, Schrag D, Somerfield MR, et al.: American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 22 (16): 3408-19, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Stage III Colon Cancer

Stage III colon cancer denotes lymph node involvement. Studies have indicated that the number of lymph nodes involved affects prognosis; patients with one to three involved nodes have a significantly better survival than those with four or more involved nodes.

Treatment Options for Stage III Colon Cancer

Treatment options for stage III colon cancer include:

- Surgery.

- Adjuvant chemotherapy.

- Clinical trials. Eligible patients can consider enrollment in carefully controlled clinical trials comparing various postoperative chemotherapy regimens.[1]

Surgery

Surgery for stage III colon cancer is wide surgical resection and anastomosis.

Evidence (laparoscopic techniques):

- The role of laparoscopic techniques [2-5] in the treatment of colon cancer was examined in a multicenter, prospective, randomized trial (NCCTG-934653 [NCT00002575]) comparing laparoscopic-assisted colectomy (LAC) with open colectomy.

- Three-year recurrence rates and 3-year overall survival (OS) rates were similar in the two groups. For more information, see the Primary Surgical Therapy section.

- The quality-of-life component of this trial has been published and minimal short-term quality-of-life benefits with LAC were reported.[6][Level of evidence A3]

Adjuvant chemotherapy

Chemotherapy regimens before 2000

Before 2000, fluorouracil (5-FU) was the only useful cytotoxic chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting for patients with stage III colon cancer. Many of the early randomized studies of 5-FU in the adjuvant setting failed to show a significant improvement in survival for patients.[7-10] These trials employed 5-FU alone or 5-FU/semustine.

Evidence (5-FU alone and 5-FU/semustine):

- The North Central Cancer Treatment Group conducted a randomized trial comparing surgical resection alone with postoperative levamisole or levamisole/5-FU.[11][Level of evidence A1]

- A significant improvement in disease-free survival (DFS) was observed for patients with stage III colon cancer who received levamisole/5-FU, but OS benefits were of borderline statistical significance.

- An absolute survival benefit of approximately 12% (49% vs. 37%) was seen in patients with stage III disease treated with levamisole/5-FU.

- In a large confirmatory intergroup trial, levamisole/5-FU- prolonged DFS and OS in patients with stage III colon cancer compared with patients who received no treatment after surgery.[12][Level of evidence A1] Levamisole alone did not confer these benefits.

- Subsequent studies tested the combination of 5-FU/leucovorin (5-FU/LV) in the adjuvant treatment of patients with resected carcinoma of the colon.

- The completed Intergroup trial 0089 (INT-0089 [NCT00201331]) randomly assigned 3,794 patients with high-risk stage II or stage III colon cancer to one of the following four treatment arms:[16]

- The Mayo Clinic regimen administered for a total of six cycles.

- The Roswell Park regimen administered for a total of four cycles.

- The Mayo Clinic regimen administered with levamisole for six cycles.

- The levamisole regimen administered for a total of 1 year.

Results:

- Five-year OS ranged from 49% for the Mayo Clinic regimen with levamisole to 60% for the Mayo Clinic regimen, and there were no statistically significant differences among treatment arms.[16][Level of evidence A1]

- A preliminary report in November 1997 demonstrated a statistically significant advantage for OS for the Mayo Clinic regimen with levamisole compared with the levamisole regimen. This difference became insignificant with longer follow-up.

- Overall, grade 3 or greater toxicity occurred more frequently for the Mayo Clinic regimen and the Mayo Clinic regimen with levamisole. In addition, the Mayo Clinic regimen was significantly more toxic with levamisole than without levamisole.

- The death rate for all four regimens ranged from 0.5% to 1%.

- Because of its ease of use and its good toxicity profile, the Roswell Park regimen became the preferred adjuvant regimen used in the United States and was often the control arm in subsequent randomized studies.

- In addition to INT-0089, multiple studies have refined the use of 5-FU/LV in the adjuvant setting and can be summarized as follows:

- Levamisole is unnecessary when using leucovorin.[16]

- Treatment that includes 6 to 8 months of 5-FU/LV is equivalent to 12 months of therapy.[17-19]

- Treatment that includes 24 weeks of adjuvant 5-FU/LV is equivalent to 36 weeks of therapy.[20]

- High-dose leucovorin is equivalent to low-dose leucovorin.[21]

- A meta-analysis of seven trials revealed no significant difference in efficacy or toxicity among patients aged 70 years or younger compared with patients older than 70 years.[22]

- An infusional de Gramont bolus and infusional 5-FU/LV schedule is safer than a bolus modified Mayo Clinic schedule of 5-FU/LV.[20]

Chemotherapy regimens after 2000

Capecitabine

Capecitabine is an oral fluoropyrimidine that undergoes a three-step enzymatic conversion to 5-FU with the last step occurring in the tumor cell. For patients with metastatic colon cancer, two studies have demonstrated the equivalence of capecitabine to 5-FU/LV.[23,24]

For patients with stage III colon cancer, capecitabine provides equivalent outcome to intravenous 5-FU/LV.

Evidence (capecitabine):

- A multicenter European study compared capecitabine (1,250 mg/m2) administered twice daily for days 1 to 14, then given every 21 days for eight cycles against the Mayo Clinic schedule of 5-FU and low-dose LV for patients with stage III colon cancer.[25]

- The study demonstrated that DFS at 3 years is equivalent for patients who received capecitabine or 5-FU/LV (hazard ratio [HR], 0.87; P < .001).[25][Level of evidence B1]

- Hand-foot syndrome and hyperbilirubinemia were significantly more common for patients receiving capecitabine, but diarrhea, nausea or vomiting, stomatitis, alopecia, and neutropenia were significantly less common.

- Of patients receiving capecitabine, 57% required a dose modification.

- For patients with stage III colon cancer in whom treatment with 5-FU/LV is planned, capecitabine is an equivalent alternative.

Oxaliplatin

Oxaliplatin has significant activity when combined with 5-FU/LV in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.

Evidence (oxaliplatin):

- In the 2,246 patients with resected stage II or stage III colon cancer in the completed Multicenter International Study of Oxaliplatin/Fluorouracil/Leucovorin in the Adjuvant Treatment of Colon Cancer study (MOSAIC [NCT00275210]), the toxic effects and efficacy of FOLFOX-4 (oxaliplatin/LV/5-FU) were compared with the same 5-FU/LV regimen without oxaliplatin administered for 6 months.[26] Based on results from the MOSAIC trial, adjuvant FOLFOX-4 demonstrated prolonged OS for patients with stage III colon cancer compared with patients receiving 5-FU/LV without oxaliplatin.[27]

- The preliminary results of the study with 37 months of follow-up demonstrated a significant improvement in DFS at 3 years (77.8% vs. 72.9%; P = .01) in favor of FOLFOX-4. When initially reported, there was no difference in OS.[27][Level of evidence B1]

- Further follow-up at 6 years demonstrated that the OS for all patients (both stage II and stage III) who entered the study was not significantly different (OS, 78.5% vs. 76.0%; HR, 0.84; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.71–1.00). On subset analysis, the 6-year OS in patients with stage III colon cancer was 72.9% in the patients receiving FOLFOX-4 and 68.7% in the patients receiving 5-FU/LV (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.65–0.97; P = .023).[27][Level of evidence A1]

- Patients treated with FOLFOX-4 experienced more frequent toxic effects consisting mainly of neutropenia (41% >grade 3) and reversible peripheral sensorial neuropathy (12.4% >grade 3).

- In a randomized phase III study (NSABP C-07 [NCT00004931]), 2,407 patients with stage II or stage III colon cancer were randomly assigned to adjuvant 5-FU/LV or fluorouracil-leucovorin-oxaliplatin (FLOX) (weekly 5-FU/LV with oxaliplatin administered on weeks 1, 3, and 5 of each 6-week cycle). DFS was the primary end point of the study.[28]

- DFS was significantly longer in the treatment group who received FLOX, but OS was not significantly different. The DFS rate was 69.4% for patients who received FLOX and 64.2% for patients who received 5-FU/LV (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.72–0.93; P = .0034).

- The OS rate at 5 years was 80.2% for patients who received FLOX and 78.4% for patients who received 5-FU/LV (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.75–1.02; P = .08).[28][Level of evidence B1]

- Grade 3 and grade 4 diarrhea was experienced by 36.9% of patients who received FLOX, and grade 3 and grade 4 dehydration was experienced by 16.1% of patients who received FLOX.

Most physicians have adopted FOLFOX as the standard of care because of toxicity concerns with weekly FLOX. FOLFOX has become the reference standard for the next generation of clinical trials for patients with stage III colon cancer.[27]

Capecitabine and oxaliplatin

The combination of capecitabine and oxaliplatin (CAPOX) is an accepted standard therapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer.

Evidence (CAPOX):

- CAPOX was evaluated in the adjuvant setting for patients with resected stage III colon cancer (capecitabine 1,000 mg/m2 bid on days 1 to 14 every 21 days and oxaliplatin 130 mg/m2 every 21 days for a total of 8 cycles).[29] A randomized phase III trial (NO16968 [NCT00069121]), randomly assigned 1,886 patients with stage III colon cancer to receive CAPOX or bolus 5FU-LV (Roswell Park or Mayo Clinic schedule).

- The 7-year DFS rates were 63% for patients who received CAPOX and 56% for patients who received bolus 5-FU/LV (HR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.69–0.93; P = .004).

- The 7-year OS rates were 73% for patients who received CAPOX and 67% for patients who received a bolus 5-FU/LV (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.70–0.99; P = .04).[29][Level of evidence A1]

Based on this trial, CAPOX has become an acceptable standard regimen for patients with stage III colon cancer.

Oxaliplatin length of therapy

Given the high rate of disabling neuropathy, the duration of oxaliplatin adjuvant therapy became an open question.

Evidence (length of therapy for oxaliplatin):

- The International Duration Evaluation of Adjuvant Therapy (IDEA) collaboration consisted of six separate randomized trials with regimens of 6 months versus 3 months of adjuvant oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy. The IDEA study was a prospective, preplanned pooled analysis of these concurrently conducted studies to evaluate the noninferiority of adjuvant therapy of either FOLFOX or CAPOX administered for 3 months versus 6 months. Noninferiority could be claimed if the upper limit of the two-sided 95% CI of the HR did not exceed 1.12.[30]

From 2007 through 2015, 13,025 patients with stage III colon cancer were enrolled in six concurrent phase III trials. Of these patients, 12,834 patients met the criteria for intention-to-treat analysis. At a median follow-up of 41.8 months, noninferiority of 3 months versus 6 months was not confirmed in the modified intention-to-treat population (HR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.00–1.15, P = .11 for noninferiority of 3 months).

- The 3-year DFS rates were 74.6% in the 3-month group and 75.5% in the 6-month group.

- Neurotoxicity of grade 2 or higher was lower in the 3-month group (16.6% for patients who received FOLFOX and 14.2% for patients who received CAPOX) than in the 6-month group (47.7% for patients who received FOLFOX and 44.9% for patients who received CAPOX). Moreover, all other toxicities were substantially lower with 3 months of treatment than with 6 months.

- A subgroup analyses observed:

- Among patients receiving FOLFOX, 6 months of therapy was superior to 3 months of therapy (HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.06–1.26; P = .001)

- Among patients receiving CAPOX, 3 months of therapy was like 6 months of therapy (HRDFS, 0.95; 95% CI, 0.85–1.06) and met the prespecified margin for noninferiority.

- Among patients with N1 tumors (<4 positive nodes), the HR was 1.07 (0.97–1.17), and among those patients with N2 tumors (≥4 positive nodes), the HR was 1.07 (0.96–1.19).

- Among patients with T4 tumors, a therapy duration of 3 months was inferior to a duration of 6 months (HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.03–1.31).

- Among patients with low-risk tumors (T1–3, N1), 3 months of therapy was noninferior to 6 months of therapy (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.90–1.12) with a 3-year DFS rate of 83.1% for patients who received 3 months of therapy and 83.3% for patients who received 6 months of therapy.

- Among patients with high-risk tumors (T4 or N2), 6 months of therapy was superior to 3 months of therapy (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.03–1.23; P = .01).

The IDEA study has generated much debate regarding the optimal length of therapy. It is recommended that patients and doctors weigh the pros and cons of potential diminished efficacy of 3 months of therapy versus the definite increased risk of toxicity, particularly neuropathy. CAPOX appears to be slightly more active than FOLFOX in the adjuvant setting.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.

References

- Rougier P, Nordlinger B: Large scale trial for adjuvant treatment in high risk resected colorectal cancers. Rationale to test the combination of loco-regional and systemic chemotherapy and to compare l-leucovorin + 5-FU to levamisole + 5-FU. Ann Oncol 4 (Suppl 2): 21-8, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Bokey EL, Moore JW, Chapuis PH, et al.: Morbidity and mortality following laparoscopic-assisted right hemicolectomy for cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 39 (10 Suppl): S24-8, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Franklin ME, Rosenthal D, Abrego-Medina D, et al.: Prospective comparison of open vs. laparoscopic colon surgery for carcinoma. Five-year results. Dis Colon Rectum 39 (10 Suppl): S35-46, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Fleshman JW, Nelson H, Peters WR, et al.: Early results of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer. Retrospective analysis of 372 patients treated by Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy (COST) Study Group. Dis Colon Rectum 39 (10 Suppl): S53-8, 1996. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schwenk W, Böhm B, Müller JM: Postoperative pain and fatigue after laparoscopic or conventional colorectal resections. A prospective randomized trial. Surg Endosc 12 (9): 1131-6, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Weeks JC, Nelson H, Gelber S, et al.: Short-term quality-of-life outcomes following laparoscopic-assisted colectomy vs open colectomy for colon cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA 287 (3): 321-8, 2002. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Panettiere FJ, Goodman PJ, Costanzi JJ, et al.: Adjuvant therapy in large bowel adenocarcinoma: long-term results of a Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 6 (6): 947-54, 1988. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Adjuvant therapy of colon cancer--results of a prospectively randomized trial. Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group. N Engl J Med 310 (12): 737-43, 1984. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Higgins GA, Amadeo JH, McElhinney J, et al.: Efficacy of prolonged intermittent therapy with combined 5-fluorouracil and methyl-CCNU following resection for carcinoma of the large bowel. A Veterans Administration Surgical Oncology Group report. Cancer 53 (1): 1-8, 1984. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Buyse M, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Chalmers TC: Adjuvant therapy of colorectal cancer. Why we still don't know. JAMA 259 (24): 3571-8, 1988. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Laurie JA, Moertel CG, Fleming TR, et al.: Surgical adjuvant therapy of large-bowel carcinoma: an evaluation of levamisole and the combination of levamisole and fluorouracil. The North Central Cancer Treatment Group and the Mayo Clinic. J Clin Oncol 7 (10): 1447-56, 1989. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Macdonald JS, et al.: Levamisole and fluorouracil for adjuvant therapy of resected colon carcinoma. N Engl J Med 322 (6): 352-8, 1990. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wolmark N, Rockette H, Fisher B, et al.: The benefit of leucovorin-modulated fluorouracil as postoperative adjuvant therapy for primary colon cancer: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project protocol C-03. J Clin Oncol 11 (10): 1879-87, 1993. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Efficacy of adjuvant fluorouracil and folinic acid in colon cancer. International Multicentre Pooled Analysis of Colon Cancer Trials (IMPACT) investigators. Lancet 345 (8955): 939-44, 1995. [PUBMED Abstract]

- O'Connell M, Mailliard J, Macdonald J, et al.: An intergroup trial of intensive course 5FU and low dose leucovorin as surgical adjuvant therapy for high risk colon cancer. [Abstract] Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 12: A-552, 190, 1993.

- Haller DG, Catalano PJ, Macdonald JS, et al.: Phase III study of fluorouracil, leucovorin, and levamisole in high-risk stage II and III colon cancer: final report of Intergroup 0089. J Clin Oncol 23 (34): 8671-8, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wolmark N, Bryant J, Smith R, et al.: Adjuvant 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin with or without interferon alfa-2a in colon carcinoma: National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project protocol C-05. J Natl Cancer Inst 90 (23): 1810-6, 1998. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Wolmark N, Rockette H, Mamounas E, et al.: Clinical trial to assess the relative efficacy of fluorouracil and leucovorin, fluorouracil and levamisole, and fluorouracil, leucovorin, and levamisole in patients with Dukes' B and C carcinoma of the colon: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project C-04. J Clin Oncol 17 (11): 3553-9, 1999. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Okuno SH, Woodhouse CL, Loprinzi CL, et al.: Phase III placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluation of glutamine for decreasing mucositis in patients receiving 5FU (fluorouracil)-base chemotherapy. [Abstract] Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 17: A-256, 1998.

- Andre T, Colin P, Louvet C, et al.: Semimonthly versus monthly regimen of fluorouracil and leucovorin administered for 24 or 36 weeks as adjuvant therapy in stage II and III colon cancer: results of a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 21 (15): 2896-903, 2003. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Comparison of flourouracil with additional levamisole, higher-dose folinic acid, or both, as adjuvant chemotherapy for colorectal cancer: a randomised trial. QUASAR Collaborative Group. Lancet 355 (9215): 1588-96, 2000. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Sargent DJ, Goldberg RM, Jacobson SD, et al.: A pooled analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy for resected colon cancer in elderly patients. N Engl J Med 345 (15): 1091-7, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Van Cutsem E, Twelves C, Cassidy J, et al.: Oral capecitabine compared with intravenous fluorouracil plus leucovorin in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: results of a large phase III study. J Clin Oncol 19 (21): 4097-106, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Hoff PM, Ansari R, Batist G, et al.: Comparison of oral capecitabine versus intravenous fluorouracil plus leucovorin as first-line treatment in 605 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: results of a randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol 19 (8): 2282-92, 2001. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Twelves C, Wong A, Nowacki MP, et al.: Capecitabine as adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med 352 (26): 2696-704, 2005. [PUBMED Abstract]

- André T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, et al.: Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 350 (23): 2343-51, 2004. [PUBMED Abstract]

- André T, Boni C, Navarro M, et al.: Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol 27 (19): 3109-16, 2009. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Yothers G, O'Connell MJ, Allegra CJ, et al.: Oxaliplatin as adjuvant therapy for colon cancer: updated results of NSABP C-07 trial, including survival and subset analyses. J Clin Oncol 29 (28): 3768-74, 2011. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Schmoll HJ, Tabernero J, Maroun J, et al.: Capecitabine Plus Oxaliplatin Compared With Fluorouracil/Folinic Acid As Adjuvant Therapy for Stage III Colon Cancer: Final Results of the NO16968 Randomized Controlled Phase III Trial. J Clin Oncol 33 (32): 3733-40, 2015. [PUBMED Abstract]

- Grothey A, Sobrero AF, Shields AF, et al.: Duration of Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Stage III Colon Cancer. N Engl J Med 378 (13): 1177-1188, 2018. [PUBMED Abstract]

Treatment of Stage IV and Recurrent Colon Cancer

Stage IV colon cancer denotes distant metastatic disease. Treatment of recurrent colon cancer depends on the sites of recurrent disease demonstrable by physical examination and/or radiographic studies. In addition to standard radiographic procedures, radioimmunoscintography may add clinical information that may affect management.[1] Such approaches have not led to improvements in long-term outcome measures such as survival.

Treatment options for stage IV colon cancer, recurrent colon cancer, and liver metastases include:

- Surgical resection of locally recurrent cancer.

- Surgical resection and anastomosis or bypass of obstructing or bleeding primary lesions in selected metastatic cases.