Mouse Study Links Immune Cells to Diarrhea Caused by Chemotherapy

, by NCI Staff

Immune cells called macrophages may help regulate the contractions of muscles lining the walls of the intestines, according to a new study in mice.

The findings may shed light onto how some chemotherapy agents cause diarrhea and could be the basis for developing new anti-diarrheal treatments for patients with cancer who experience chemotherapy-induced diarrhea, researchers at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis reported in Immunity on July 17.

Diarrhea is a frequent side effect of certain chemotherapy agents. Severe diarrhea may cause some individuals receiving chemotherapy to reduce the dose or to stop treatment altogether.

The Washington University researchers found that macrophages were part of a previously unknown signaling pathway that participates in controlling the activity of smooth muscle cells in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

This signaling pathway is necessary for normal smooth muscle contractions, or motility, in mice, the researchers concluded. It was through this pathway that the chemotherapy drug irinotecan (Camptosar) caused diarrhea in mice, they noted.

"This is an excellent, novel, and provocative study," said Simon J. Gibbons, Ph.D., of the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, who investigates the GI system but was not involved in the study. "There are many potential applications for human health," including new treatments for chemotherapy-induced GI side effects such as abdominal pain and diarrhea.

Focusing on a Macrophage Linked to Chronic Itching

It has recently become clear that macrophages affect neurons in the GI tract that send signals to smooth muscle cells in the gut, causing them to contract and relax when appropriate, Dr. Gibbons noted. There are approximately as many neurons in the gut as there are in the brain.

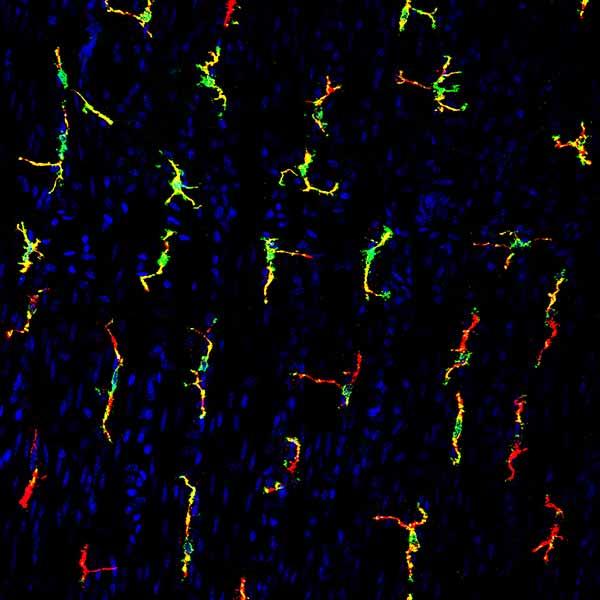

Although the smooth muscle layers of the gut are also home to a large population of macrophages, “the role of these cells in maintaining GI motility has not been clear,” said Hongzhen Hu, Ph.D., of Washington University, who co-led the study with Brian S. Kim, M.D.

To learn more about the role of macrophages in gut motility, the researchers focused on macrophages that have a channel protein on their cell surfaces called the transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4).

The family of TRP channel proteins enables individual cells to detect changes in their local environments, such as heat and the movement of food through the intestine. In previous work led by Drs. Hu and Kim at the Center for the Study of Itch at Washington University, TRPV4 had been linked to chronic itching.

In the current study, the TRPV4 protein triggered the release of molecules called prostaglandins. These molecules in turn interact with the smooth muscle cells in the intestines to maintain normal GI motility.

"We learned that macrophages are acting like neurons in the gut," Dr. Kim explained. "The immune cells are triggering the contraction of the smooth muscles in the gut independently of nerve cells."

An Expanding View of Macrophages

The new findings add to a growing body of knowledge about the biological roles of macrophages. "Macrophages do much more than help the immune system," Dr. Gibbons said. "It is increasingly evident that macrophages are central to the normal physiological functioning of many tissues, including the gut and the brain."

Using genetic tools and pharmacological agents, the Washington University researchers found that macrophages expressing the TRPV4 channel appeared to be necessary for the normal functioning of the GI tract in the mice. When the channel was altered or blocked, GI motility slowed.

"We all think that the immune system is there to fight off infections, but it turns out that the immune system is also important in the gut for other reasons," said Dr. Kim.

Reversing Chemotherapy-Induced Diarrhea

Next, the researchers found that giving the mice the chemotherapy agent irinotecan altered the expression of TRPV4 protein and affected the GI functions in the animals. But by blocking the activity of TRPV4 in the mice, the researchers reduced symptoms such as diarrhea.

"The idea that immune cells are regulating a mechanical process in the intestines is exciting, because it opens new avenues to develop treatments not just for chemotherapy-induced diarrhea but for other bowel disorders as well, including irritable bowel syndrome," Dr. Kim said.

The movement of contents in the GI tract is a very complex process that depends on a variety of different types of cells, Dr. Gibbons cautioned, noting that more research is needed to better understand the newly identified signaling pathway in mice and in humans.

Nonetheless, Dr. Gibbons continued, "companies have developed small molecules targeting TRPV4 and these could be exploited to modulate GI motility."