Oncolytic Virus Therapy Shows Benefit in Patients with Melanoma

, by NCI Staff

In a phase III clinical trial, an investigational virus-based immunotherapy, talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC), significantly increased the durable response rate in patients with metastatic melanoma compared with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF).

The treatment appears to work by directly killing cancer cells and stimulating an immune response against tumors, the trial investigators believe. Findings from the trial were published May 26 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

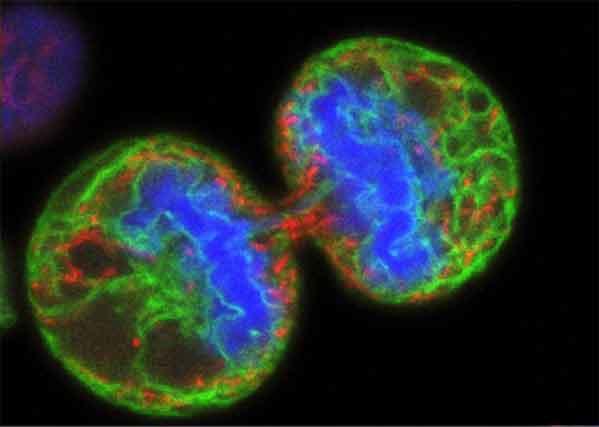

T-VEC is an oncolytic virus, a virus that selectively replicates inside and kills cancer cells. This particular oncolytic virus is based on herpes simplex virus type 1 and has been modified to include a gene that codes for GM-CSF, a protein that stimulates the production of immune cells in the body.

Although the oncolytic virus can enter cancer cells and normal cells alike, normal cells have mechanisms to kill the virus whereas cancer cells do not. As the virus replicates, it causes cancer cells to burst and die. The dying cells release new viruses, GM-CSF, and a variety of tumor-specific antigens that can stimulate an immune response against cancer cells throughout the body.

“The importance of this trial is that this is the first oncolytic virus to show benefit in patients with cancer,” said the trial’s lead investigator, Howard Kaufman, M.D., of the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey.

In the international phase III trial, called OPTiM, 436 patients with unresectable stage IIIB to IV melanoma were randomly assigned to receive either T-VEC or GM-CSF. T-VEC was injected directly into the tumors, and subsequent doses were administered 3 weeks after the first dose, then once every 2 weeks. GM-CSF was administered subcutaneously every day for 14 days, in 28-day cycles.

The durable response rate, which was measured as an objective response to therapy that lasted for at least 6 months, was significantly higher in patients who received T-VEC (16.3 percent) than in those who received GM-CSF (2.1 percent). T-VEC also improved median overall survival, which was 23.2 months in the T-VEC arm and 18.9 months in the GM-CSF arm.

“The complete response rate in the T-VEC arm was 10.8 percent, which included both tumors that were injected and those that were uninjected,” Dr. Kaufman noted. “This indicates that the therapy likely generated a systemic immune response,” he explained. “As yet, little is understood about how T-VEC triggers the systemic immune response,” he said, and this is a “priority for future research.”

Chills, injection-site pain, nausea, flu-like symptoms, and fatigue were some of the most common side effects observed in the study. “The therapy is well tolerated and most side effects were low grade,” said Dr. Kaufman. “There were very few serious adverse events related to T-VEC and no treatment-related deaths.”

Because the therapy is well tolerated, it shows promise for use in combination with other agents, he continued. Trials investigating the effectiveness of T-VEC in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors are already under way. “We hope to expand this therapy to other types of cancer,” he added.

The improvements in duration of response to treatment and overall survival are “clinically meaningful,” said James Gulley, M.D., Ph.D., of NCI’s Center for Cancer Research.

Dr. Gulley agreed that the regression in tumors that were not injected strongly suggests that the therapy works in part by inducing an immune response, which, he said, “provides a rationale for combination studies with a growing number of immuno-oncology agents that have shown activity in melanoma or other tumors.”

Amgen, which manufactures T-VEC, has submitted the drug to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for approval.