Types of cancer treated with stem cell transplants

Stem cell transplants are most often used to treat people with cancers that affect blood cells, such as leukemia, lymphoma, multiple myeloma, and myelodysplastic syndromes. They may also be used for neuroblastoma, Ewing sarcoma, brain tumors that have come back in children, germ cell tumors, and testicular cancer.

Stem cell transplants are also used for other blood disorders, such as aplastic anemia, sickle cell disease, and autoimmune diseases.

Stem cell transplants for other types of cancer are being studied in clinical trials, which are research studies involving people. To find a study that may be an option for you, see Find a Clinical Trial.

How stem cell transplants work against cancer

Stem cell transplants do not usually work against cancer directly. Instead, they restore your body's ability to produce new blood cells after treatment with the very high doses of chemotherapy and maybe other treatments, such as radiation therapy, that are used to destroy cancer cells.

But in leukemia, the stem cell transplant may work against cancer directly. This happens because of an effect called graft-versus-tumor or graft-versus-leukemia, which can occur after transplants that use stem cells from a donor. This effect occurs when white blood cells from your donor (the graft) attack any cancer cells that remain in your body (the tumor or leukemia cells). This effect improves the chances of success of the transplant.

Types of stem cell transplants

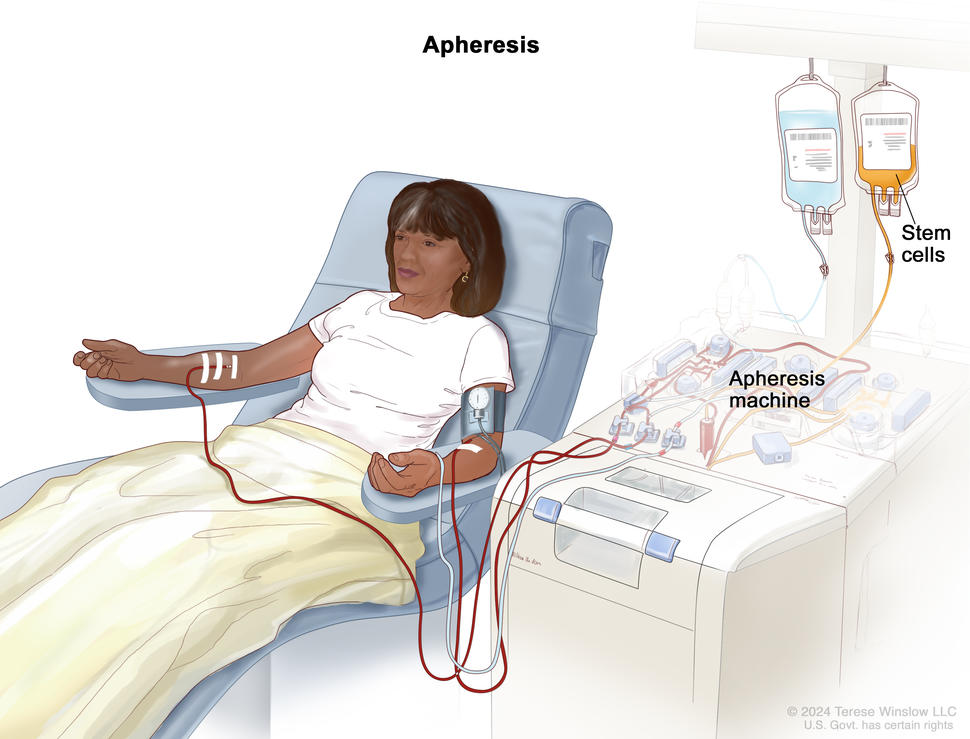

In a stem cell transplant, you receive healthy blood-forming stem cells through a needle in your vein. Most of the blood-forming stem cells that are used in transplants come from the bloodstream. When stem cells come from the blood, the transplant may be called a peripheral blood stem cell transplant, or PBSCT. But blood stem cells can also come from the bone marrow or umbilical cord, which is blood collected when a baby is born. When the stem cells come from the bone marrow, the procedure may be called a bone marrow transplant, or BMT. When they come from cord blood, the procedure may be called a cord blood transplant.

Once they enter your bloodstream, the stem cells travel to the bone marrow, where they take the place of the cells that were destroyed by treatment. Transplants can be:

- autologous, which means the stem cells come from you, the person with cancer

- allogeneic, which means the stem cells come from someone else. The donor may be a blood relative or someone who is not related, if the cells are a close enough match to yours

- syngeneic, which means the stem cells come from your identical twin

There are benefits and risks to both autologous and allogeneic stem cell transplants. With autologous transplants, the transplanted cells will match. But there is a small risk that cancer cells will be transplanted.

With allogeneic transplants, it is important that the cells match closely enough that your immune system won’t see the transplanted blood stem cells as foreign and destroy them.

Mini-transplants are a type of allogeneic transplant that use lower doses of cancer treatment than a regular transplant. They do not kill all your blood-forming stem cells, but they still kill some of the cancer cells. This type of allogeneic transplant can prevent rejection of the donor’s stem cells by suppressing your immune system.

Tandem transplants are a type of autologous transplant. During a tandem transplant, you receive a round of high-dose chemotherapy followed by a stem cell transplant. Then after many weeks or months, you have another round of high-dose chemotherapy followed by another stem cell transplant.

Whether a stem cell transplant is right for you and which type you might have depends on many factors, such as:

- the type of cancer you have

- how advanced your cancer is

- if you can use your own stem cells

- if matching donor stem cells are available

- if there are other treatments that are likely to work for your cancer

- if you can tolerate high doses of chemotherapy

- if you have other serious health problems

- other treatments you’ve had in the past

Your doctor will carefully weigh these issues with the risks and benefits of each type of stem cell transplant and discuss them with you.

How blood-forming stem cells are matched

To decide if the stem cells from a donor are a match for you, they will be tested for their HLAs (which stands for human leukocyte antigens). HLAs are sets of proteins, or markers, that you have on most cells in your body. Each person has a different set of HLAs. The more HLAs that you and the donor have in common, the better the chance that your body will accept the donor’s stem cells.

Most often, the best match for an allogeneic stem cell transplant is a brother or sister.

See Donating Blood Stem Cells for Stem Cell Transplants to learn about stem cell donation.

Stem cell transplant side effects

The high doses of cancer treatment that you have before a stem cell transplant can cause problems such as:

- bleeding

- increased risk of infection

- feeling tired and exhausted

Stem cell transplants may cause both short- and long-term problems. Short-term problems may include:

- nausea

- vomiting

- fatigue

- loss of appetite

- mouth sores

- hair loss

- skin reactions

Long-term problems of stem cell transplants may include:

- infertility

- cataracts (clouding of the lens of the eye, which causes loss of vision)

- new secondary cancers

- liver, kidney, lung, or heart damage

- bone and muscle weakness

Talk with your doctor or nurse about side effects that you might have, how serious they might be, and what to do about them.

Tell your doctor or nurse if you have trouble eating during stem cell transplant. You might find it helpful to speak with a dietitian.

For more information about side effects and how to manage them, see Side Effects of Cancer Treatment.

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)

If you have an allogeneic transplant, you might develop a serious problem called graft-versus-host disease. Graft-versus-host disease can occur when white blood cells from your donor (the graft) see cells in your body (the host) as foreign and attack them. This problem can cause damage to your skin, liver, intestines, and many other organs.

Graft-versus-host disease can be acute or chronic. Acute graft-versus-host disease occurs within the first 3 months after transplant. Chronic graft-versus-host disease occurs 3 months after a transplant or later.

Graft-versus-host disease can be treated with steroids or other drugs that suppress your immune system.

There are a few ways that the risk of graft-versus-host disease can be reduced.

- The closer your donor’s stem cells match yours, the less likely you are to have graft-versus-host disease.

- Your doctor may give you drugs to suppress your immune system.

- Donated stem cells can be treated to remove the white blood cells (called T cells) that cause graft-versus-host disease. This process is called T-cell depletion.

How much stem cell transplants cost

Stem cells transplants are complicated procedures that are very expensive. They require long hospital stays at special treatment centers and require the services of many health care providers. If you do not live nearby, you will need to stay in a hotel or apartment when you are not in the hospital. If you have no problems, you can go home 100 days after you’ve received the donor stem cells. But you will need to be closely followed by a doctor who has experience in taking care of people who have had a stem cell transplant.

Transplants can cause serious side effects that can be expensive to manage.

If you need to travel for treatment, you might have extra costs for transportation, housing, and childcare.

Most insurance plans cover some of the costs of transplants for certain types of cancer. Talk with your health plan about which services it will pay for. The business office of your treatment center may help you understand all the costs involved.

For information about groups that may be able to provide financial help, contact NCI’s Cancer Information Service.

Where you go for a stem cell transplant

When you need an allogeneic stem cell transplant, you will need to go to a hospital that has a specialized transplant center. The National Marrow Donor Program® maintains a list of transplant centers in the United States.

How long it takes to have a stem cell transplant

A stem cell transplant can take a few months to complete. The process begins with treatment with high doses of chemotherapy and maybe radiation therapy. This treatment goes on for a week or two. Once you have finished, you will have a few days to rest.

Next, you will receive the blood stem cells. The day you receive your stem cells is often called “day zero.” The stem cells will be given to you through an intravenous (IV) catheter. This process is like receiving a blood transfusion. It takes 1 to 5 hours to receive all the stem cells.

After receiving the stem cells, you begin the recovery phase. During this time, doctors will follow the progress of the new blood cells by checking your blood counts often. As the new stem cells produce blood cells, your blood counts will go up.

Even after your blood counts return to normal, it takes much longer for your immune system to fully recover—several months for autologous transplants, and 1 to 2 years for allogeneic or syngeneic transplants.

How you may feel after a stem cell transplant

Stem cell transplants affect people in different ways. How you feel depends on:

- the type of transplant that you have

- the doses of treatment you have before the transplant

- how you respond to the high-dose treatments

- your type of cancer

- how advanced your cancer is

- how healthy you were before the transplant

Since people respond to stem cell transplants in different ways, your doctor or nurses cannot know for sure how the procedure will make you feel.

Working during a stem cell transplant

Whether or not you can work during a stem cell transplant may depend on the type of job you have. The process of a stem cell transplant, with the high-dose treatments, the transplant, and recovery, can take many months. You will be in and out of the hospital during this time. Even when you are not in the hospital, sometimes you will need to stay near it, rather than staying in your own home.

You will be more tired and your ability to concentrate on work may be affected. You will be visiting the hospital two or three times a week after discharge. You may need to spend a few hours in the hospital for blood or platelet transfusions or replacing minerals in your body.

So, if your job allows, you may want to arrange to work remotely part-time. Many employers are required by law to change your work schedule to meet your needs during cancer treatment. Talk with your employer about ways to adjust your work during treatment. You can learn more about these laws by talking with a social worker.

For more information about working with cancer and your legal rights, see Going Back to Work.

Stem cell transplants in clinical trials

If you are interested in finding a stem cell transplant clinical trial, use the advanced clinical trials search form or contact NCI's Cancer Information Service.