What is colorectal cancer?

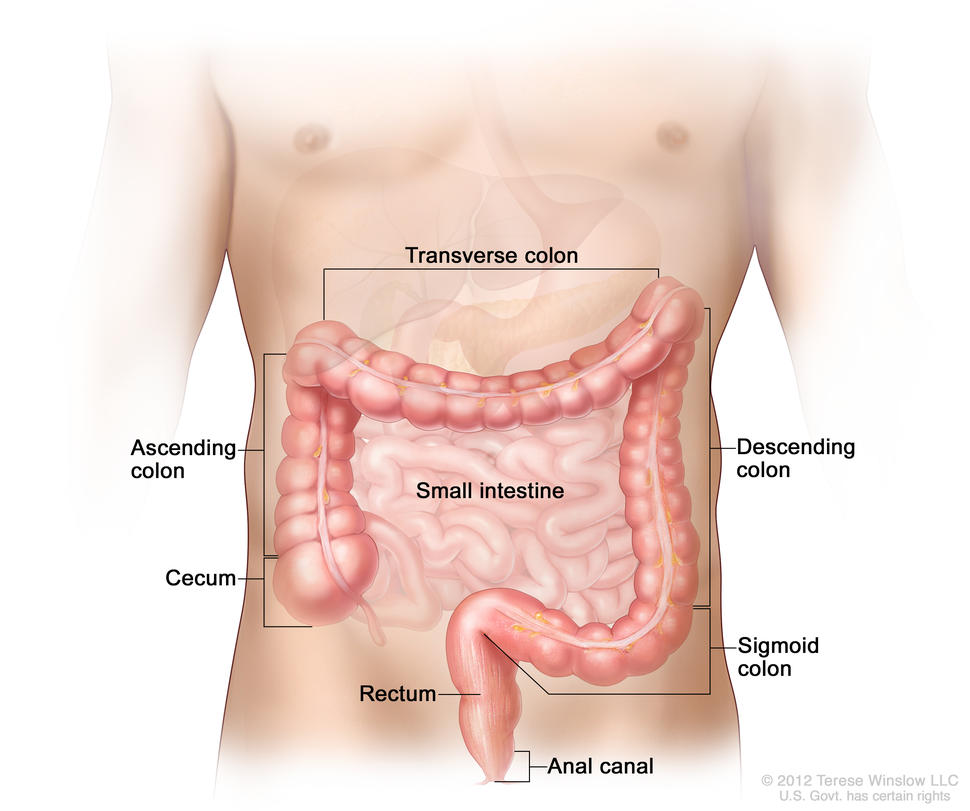

Colorectal cancer (cancer that develops in the colon and/or the rectum) is a disease in which abnormal cells in the colon or rectum divide uncontrollably, ultimately forming a malignant tumor.

Most colorectal cancers begin as an abnormal growth, or lesion, in the tissue that lines the inner surface of the colon or rectum. Lesions may appear as raised polyps, or, less commonly, they may appear flat or slightly indented. Raised polyps may be attached to the inner surface of the colon or rectum with a stalk (pedunculated polyps), or they may grow along the surface without a stalk (sessile polyps).

Colorectal polyps are common in people older than 50 years of age, and most do not become cancer. However, a certain type of polyp known as an adenoma is more likely to become a cancer.

Colorectal cancer is the third most common type of non-skin cancer in both men (after prostate cancer and lung cancer) and women (after breast cancer and lung cancer). It is the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States after lung cancer. In 2024, an estimated 152,810 people in the United States will be diagnosed with colorectal cancer and 53,010 people will die from it (1).

Who is at risk for colorectal cancer?

Increasing age is a major risk factor for colorectal cancer. In the United States, colorectal cancer is most frequently diagnosed in adults aged 65 to 74 years. From 2017 through 2021, the colorectal cancer incidence rates were 8.6, 69.8, and 156.9 per 100,000 people for those younger than 50 years, those aged 50 to 64 years, and those 65 years and older, respectively.

However, colorectal cancer incidence is increasing among younger age groups even as it is declining in older age groups. For example, from 2012 through 2021, the number of new colorectal cancer cases diagnosed per 100,000 people

- increased 3.8% per year among those aged 15 to 39 years, from 4.1 to 5.6

- increased 1.2% per year among those aged 40 to 64 years, from 46.1 to 52.1

- decreased 2.2% per year among those aged 65 to 74 years, from 148.2 to 120.8

- decreased 2.7% per year among those 75 years and older, from 244.9 to 192.7

The reason(s) for the increasing incidence among younger people is not known, but it may relate to changes in the prevalence of certain risk factors.

Besides age, other major risk factors for colorectal cancer include certain inherited conditions (such as Lynch syndrome and familial adenomatous polyposis), a family history of colorectal cancer, and a personal history of inflammatory bowel disease (such as ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease).

Several other factors are known to be associated with smaller increases in risk. These include moderate to heavy alcohol use, obesity, physical inactivity, and cigarette smoking.

In addition, people with a history of inflammatory bowel disease (such as ulcerative colitis or Crohn disease) have a higher risk of colorectal cancer than people without such conditions.

What do colorectal cancer screening guidelines say about who should have colorectal cancer screening?

Expert medical groups, including the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (2), strongly recommend screening for colorectal cancer. Although some details of the recommendations vary, most groups now generally recommend that people at average risk of colorectal cancer get screened at regular intervals beginning at age 45 (2–6).

The expert medical groups generally recommend that screening continue to age 75; for those aged 76 to 85 years, the decision to screen is based on the individual’s life expectancy, health conditions, and prior screening results.

People who are at increased risk of colorectal cancer because of certain inherited conditions (such as Lynch syndrome and familial adenomatous polyposis), a family history of colorectal cancer, a personal history of advanced polyps, or because they have inflammatory bowel disease may be advised to start screening earlier and/or have more frequent screening.

What methods are used to screen people for colorectal cancer?

Several different screening tests are available that can help doctors find colorectal cancer before symptoms begin, when it may be more treatable. Some of these tests also allow adenomas and polyps to be found and removed before they become cancer. That is, some types of colorectal cancer screening may allow for cancer prevention in addition to early detection.

- Stool tests. Both polyps and colorectal cancers can bleed, and stool tests check for tiny amounts of blood in feces (stool) that cannot be seen visually. (Hidden blood in stool—also called occult blood–may also indicate the presence of conditions that are not cancer, such as hemorrhoids.) With these tests, stool samples are collected by the patient using a kit, and the samples are sent to a laboratory for testing. People who have a positive finding with these tests are advised to have a colonoscopy.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved several types of stool tests to screen for colorectal cancer, including:- Guaiac fecal occult blood test (gFOBT). gFOBT uses a chemical to detect heme, a component of the blood protein hemoglobin. Because gFOBT can also detect heme in some foods (for example, red meat), people must avoid certain foods before having this test. If gFOBT is the only type of colorectal cancer screening test performed, experts generally recommend testing every year or two (3).

- Fecal immunochemical test (FIT or iFOBT). FIT uses antibodies to detect hemoglobin protein specifically (5, 6). Dietary restrictions are typically not required for FIT. If FIT is the only type of colorectal cancer screening test performed, experts generally recommend testing every year or two (3).

- Multitarget stool DNA testing (sDNA-FIT). sDNA-FIT (Cologuard) detects hemoglobin, along with certain DNA biomarkers. The DNA comes from cells in the lining of the colon and rectum that are shed and collect in stool as it passes through the large intestine and rectum. Experts generally suggest sDNA-FIT testing at least every 3 years (2).

- Direct visualization tests. There are three direct visualization tests used for colorectal cancer screening. All involve pumping air into the colon through a tube inserted through the anus into the rectum to expand the colon so the doctor can see the lining more clearly. Of these three tests, colonoscopy is the most common direct visualization test in the United States.

- Colonoscopy. In this test, the rectum and entire colon are examined using a colonoscope, a flexible lighted tube with a lens for viewing and a tool for removing tissue, which is inserted through the anus into the rectum. During colonoscopy, any abnormal growths in the entire colon and the rectum can be removed. The preparation for colonoscopy requires a thorough cleansing of the entire colon before the test. Most patients receive some form of sedation during the test.

Experts recommend screening colonoscopy every 10 years for people at average risk. - Virtual colonoscopy, also called computed tomographic (CT) colonography, is a screening method that uses special x-ray equipment (a CT scanner) to produce a series of pictures of the colon and the rectum from outside the body. A computer then assembles these pictures into detailed images that can show polyps and other abnormalities. As with standard colonoscopy, a thorough cleansing of the colon is necessary before this test. Virtual colonoscopy is much less invasive than standard colonoscopy (other than the pumping of air into the colon), but if polyps or other abnormal growths are found during a virtual colonoscopy a standard colonoscopy must usually be performed to remove them.

Because virtual colonoscopy also produces images of areas outside the colon and rectum it can lead to the unintentional discovery of medical findings in these areas that require additional follow-up procedures. Virtual colonoscopy may also miss small polyps (7). However, many small polyps may not be likely to become cancer and so taking them out may not be of benefit. Experts recommend screening with virtual colonoscopy every 5 years. - Sigmoidoscopy. In this test, the rectum and sigmoid colon are examined using a sigmoidoscope, a flexible lighted tube with a lens for viewing and a tool for removing tissue, which is inserted through the anus into the rectum and sigmoid colon. During sigmoidoscopy, abnormal growths in the rectum and sigmoid colon can be removed for analysis (biopsied). The lower colon must be cleared of stool before sigmoidoscopy, but the preparation is not very extensive. People are not usually sedated for this test.

Experts generally recommend screening sigmoidoscopy every 5 or 10 years for people at average risk (3). People who are screened with sigmoidoscopy may also be tested every few years with FIT.

- Colonoscopy. In this test, the rectum and entire colon are examined using a colonoscope, a flexible lighted tube with a lens for viewing and a tool for removing tissue, which is inserted through the anus into the rectum. During colonoscopy, any abnormal growths in the entire colon and the rectum can be removed. The preparation for colonoscopy requires a thorough cleansing of the entire colon before the test. Most patients receive some form of sedation during the test.

- Blood-based tests. A test for a molecular biomarker (methylated SEPT9) shed by colorectal cancer cells into the bloodstream, called Epi proColon 2.0, is FDA approved to be used to screen adults 50 years or older at average risk for colorectal cancer who have been offered and have a history of not completing colorectal cancer screening using a stool test or a direct visualization test.

Another blood-based test for colorectal cancer (Shield) is approved for screening adults ages 45 and older who are at average risk for the disease. It analyzes plasma DNA for certain changes, including the presence of harmful gene variants.

Blood-based tests have not yet been incorporated into clinical guidelines for first-line colorectal cancer screening.

- Other methods. Several other tests to screen for colorectal cancer are sometimes used, although these are not generally recommended by expert groups.

- Double-contrast barium enema (DCBE). This test is another method of visualizing the colon from outside the body. In DCBE, a series of x-ray images of the entire colon and rectum is taken after the patient is given an enema with a barium solution. The barium helps to outline the colon and the rectum on the images. DCBE is rarely used for colorectal cancer screening; however, it may be used for people who cannot undergo standard colonoscopy—for example, because they are at particular risk for complications.

- Single-specimen gFOBT done in a doctor's office. Doctors sometimes perform gFOBT on a stool sample collected during a digital rectal examination as part of a routine physical examination. However, this approach is not an effective way to screen for colorectal cancer (8).

How can people and their health care providers decide which colorectal cancer screening test(s) to use?

Different tests have different advantages and disadvantages, and people should talk with their health care provider about which test is best for them.

An individual's decision about which test to have may depend on:

- the person’s age, medical history, family history, and general health

- potential harms of the test (more invasive tests have more potential harms than less invasive tests)

- the preparation required for the test

- whether sedation may be needed for the test

- the follow-up care needed after the test

- the convenience of the test

- the cost of the test and the availability of insurance coverage

The table below summarizes key features of the different colorectal screening tests that people may want to consider when choosing a test.

| Test | Diet and medication changes before test? | Invasive procedure? | Preparation (colon cleansing) needed? | Sedation needed? | Test frequency | Additional considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stool tests | Yes for gFOBT, no for FIT, sDNA-FIT, or mt-sRNA | No | No | No | Every year to every 3 years, depending on the test |

|

| Sigmoidoscopy | Yes | Yes | Yes (less extensive than for colonoscopy) | Usually no | Every 5 to 10 years, possibly with more frequent FIT |

|

| Colonoscopy | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Every 10 years |

|

| Virtual colonoscopy | No | Yes (minimally) | Yes | No | Every 5 years |

|

Does health insurance pay for colorectal cancer screening?

Colorectal cancer screening is a preventive service that the Health Insurance Marketplace and many other health insurance plans are required to cover. Medicare covers several colorectal cancer screening tests for its beneficiaries. However, Medicare and some insurance companies currently do not pay for the costs of virtual colonoscopy. Specific information about Medicare benefits for colorectal cancer screening is available on the Medicare website.

A colonoscopy to follow up on a screening test with a positive result, such as an abnormal stool test or even a lesion detected on a screening colonoscopy, is considered a diagnostic exam and may or may not be covered (or not covered as fully as a screening colonoscopy). Some insurers consider a screening colonoscopy that reveals a polyp that must be removed to be a diagnostic exam and charge accordingly. People should check with their health insurance provider before their test to determine their colorectal cancer screening coverage and what their out-of-pocket expenses may be if the test finds an abnormality that needs to be followed up.

What happens if a colorectal cancer screening test finds an abnormality?

If an abnormality is found during a standard colonoscopy it will be removed (polypectomy) or a biopsy performed, and the cells will be examined to see if cancer is present. If an abnormality is found during a sigmoidoscopy, polypectomy or biopsy may or may not be performed, and a follow-up colonoscopy may be recommended. If a different screening test finds an abnormality, a colonoscopy will be needed to examine the colon directly.

What new tests are being developed for colorectal cancer screening?

Researchers are studying new blood markers to detect colorectal cancer early. For example, tumors release into the blood small fragments of RNA called microRNAs packaged into tiny sac-like structures called exosomes. Exosome-packaged microRNAs have shown promise for early detection of pancreatic cancer and may also be useful for early detection of colorectal cancer (10, 11).

Another approach being tested is whether artificial intelligence (AI)–based technology called computer-aided detection (CAD) can improve the interpretation of colonoscopy imaging by experienced doctors. Several clinical trials have found that the addition of CAD increased the detection of small polyps that are unlikely to become cancer but not of advanced adenomas. However, these studies used relatively primitive AI-based CADs. Newer AI technologies may improve the detection of advanced adenomas by CAD.

Researchers are continuing to improve the sensitivity of stool-based screening for detecting advanced adenomatous polyps, which can potentially become colorectal cancer, by testing for the presence of other (non-DNA) types of biomarkers. For example, a multitarget stool RNA (mt-sRNA) test (ColoSense) that detects occult hemoglobin (with FIT), along with levels of eight colorectal cancer–associated RNA markers was approved in 2024 for colorectal cancer screening. (This test is not yet commercially available, and experts have not yet recommended a screening interval for it.)

Researchers have also found that measuring three protein biomarkers in stool—hemoglobin, calprotectin, and serpin family F member 2—improved the ability of FIT to detect advanced lesions (including colorectal cancer) without reducing its specificity (12).

Capsule colonoscopy (also called capsule endoscopy) is a technique that continues to be explored to improve visualization of the colon. A person swallows a pill-like capsule that contains a tiny wireless camera. The camera takes pictures of the inside of the digestive tract and sends them to a small recorder that is worn on the patient’s waist or shoulder. The pictures are then viewed on a computer by the doctor to check for signs of disease. The capsule passes out of the body during a bowel movement. Cleansing of the colon is still necessary before this test. This method is currently approved for patients with an incomplete colonoscopy and for detection of colon polyps in patients with evidence of lower GI bleeding but not as a stand-alone screening test for people at average risk.